As researchers find more security flaws in Oracle Java, the software continues to be used for exploitation and malware delivery. This year has been a shaky start for the cross-platform web technology, where it seems the number of documented vulnerabilities is hard to number.

If you recall in January, we saw a zero-day later found to be responsible for intrusions into companies like Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, and Twitter. Then in February, after seeing a Java patch with over 50 security fixes, reports surfaced thereafter that Bit9 was hacked using a separate java zero-day. Even still in March, an emergency patch was issued to address even more vulnerabilities.

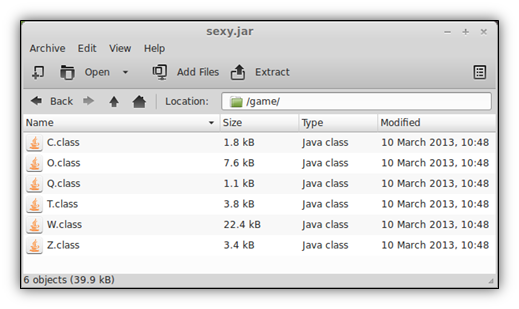

Because we’re seeing java used more in malware, it’s important for researchers to know how to analyze and understand java code.Let’s take a look at one java archive (“jar”) we’ve seen in the wild that not only contains multiple exploits but also has an encrypted malware payload. This sample was provided by Malwarebytes researcher Jerome Segura and is called “sexy.jar”. The landing page, “sexy.html”, loads the jar as an applet and points to Q.class, a Java class file within the jar. To get more details on this, check out Segura’s blog entry on this here.

It’s important to understand that a jar is essentially just a zip archive, a file-format you’ve probably seen since you started using computers. Inside the archive are various things, most important of which are class files, or compiled java bytecode. This bytecode is executed within a Java Virtual Machine (JVM), part of the Java Runtime Environment (JRE), a term dubbed by Oracle describing Java’s execution environment. Many of you with Java installed on your computer use the JRE every day when you visit your favorite websites.

In order to streamline analysis of java class files, we can use a popular tool known as a Decompiler, which attempts to decompile programs into their original source code. The Java Decompiler project offers a graphical utility called “JD-GUI” for displaying Java sources, and is my personal favorite and one of the best in the field. Another great tool for those who prefer the command-line is JAD, which essentially does the same thing and can be found here. Both of these tools are available on Windows, Mac, and UNIX-based systems.

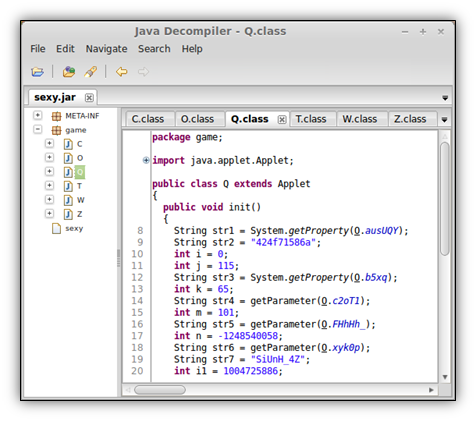

Analysis Let’s go ahead and take our jar and decompile it using JD-GUI. After that, we can view the code statically and attempt to understand what’s going on.

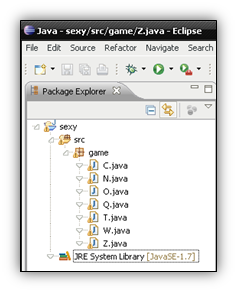

When we load sexy.jar into JD-GUI, we see a package called “game” and six class files, along with another file titled “sexy”. As I mentioned before, the “Q” class in the jar is loaded as an applet, which will reference other packaged class files throughout execution. The file labeled “sexy” contains an encrypted malware payload that will be dropped to the disk and executed. This is not a traditional approach as a jar usually doesn’t contain the malware itself.

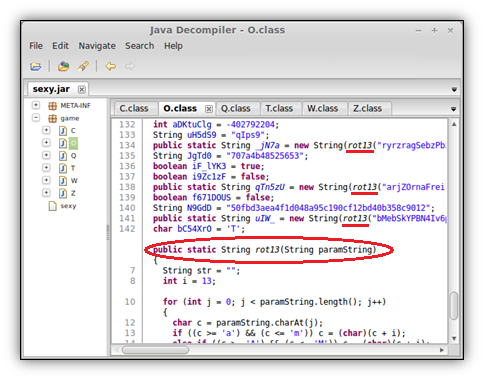

You’ll instantly notice that all the strings are part of the “O” class. These are all encrypted using rot13, a simple substitution cipher that I talked about here. You’ll notice that every string declared in this class is first passed through the rot13 function at the bottom of the code.

Here are the decrypted strings used in this jar:

J 1.7 java.security.AllPermission com.sun.jmx.mbeanserver.JmxMBeanServer javax.management.MBeanServerDelegate declaredMethods game.N oZroFxLCOA4Vi6ck_oH getMBeanInstantiator add java.security.CodeSource java.security.ProtectionDomain set java.io.tmpdir oZroFxLCOA4Vi6ck_oH sun.org.mozilla.javascript.internal.GeneratedClassLoader file: javax.management.MBeanServer oZroFxLCOA4Vi6ck_oH com.sun.jmx.mbeanserver.MBeanInstantiator sun.org.mozilla.javascript.internal.Context XrwfQ_w.exe G java.version aced0005757200135b4c6a6176612e6c616e672e4f626a6563743b... java.security.cert.Certificate java.io.tmpdir com.sun.jmx.mbeanserver.Introspector java.security.Permission findClass os.name Windows P java.security.PermissionCollection GWiL2S.exe java.security.Permissions elementFromComplex newMBeanServer oZroFxLCOA4Vi6ck_oH

The jar uses two exploits against the JVM to run the decrypted payload: CVE-2012-0507 and CVE-2013-0422.

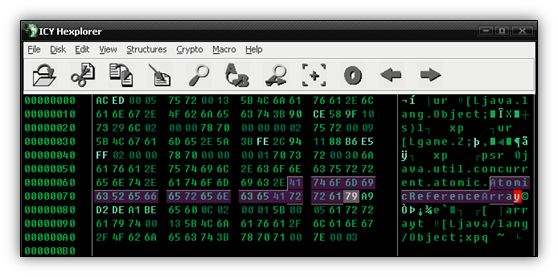

CVE-2012-0507 The CVE-2012-0507 exploit is attempted first, implemented in the C and Z classes. CVE-2012-0507 is a vulnerability in the JRE that occurs because the AtomicReferenceArray class does not check if an array is of an expected Object[] type (you can read more about this here).

The C class contains a long hex string (as seen above) that decodes to methods used for the exploit.

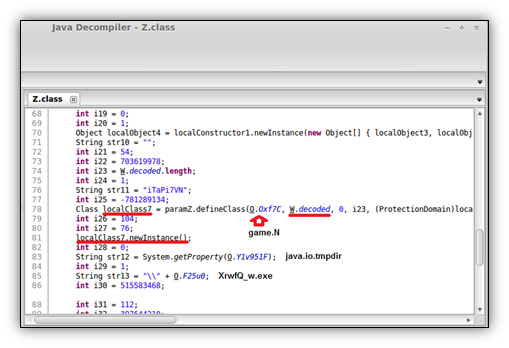

Eventually the “Z” class creates a new class during runtime (game.N) to drop the malware in %temp%XrwfQ_w.exe

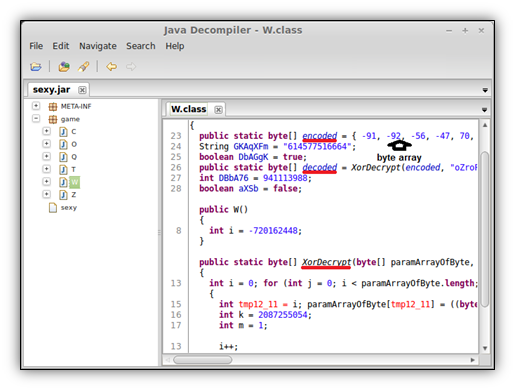

The new class first has to be decoded in the “W” class XorDecrypt function; this takes a large encrypted bytecode array called encoded and decrypts it as the “N” class.

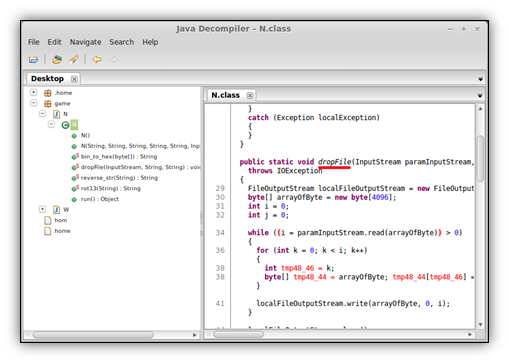

Finally we can see the file is decrypted and dropped within the “N” class, using the dropFile function.

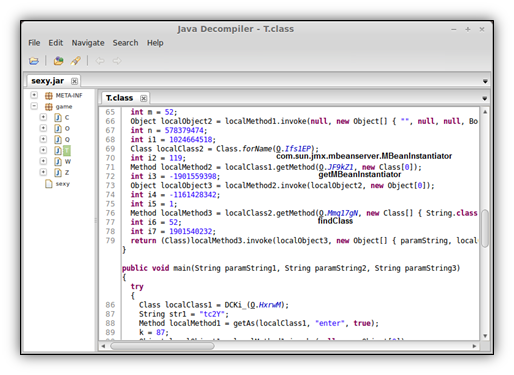

CVE-2013-0422 The second exploit, CVE-2013-0422 is called if you’re running Java 7 and is implemented in the T class. The exploit uses a private mBeanInstantiator object and the findClass method to reference arbitrary classes, which in this case is also our embedded “N” class. If the jar takes this exploit route, the payload is dropped in in %temp%GWiL2S.exe

Debugging an applet In some situations you might want to see things dynamically as they execute instead of the plain static view. This can be accomplished with our jar by debugging it as an applet.

Debugging a jar isn’t as straightforward as a native system binary, like an EXE. One of the best methods I’ve found is using the Eclipse IDE for Java Developers to step through the code. However, if you’re going to take this route, you’re going to need to do a little prep work.

First we’ll need to overwrite library files in the JRE install directory with those from the Java Development Kit (JDK), a tool used to assist Java developers. We need to do this because the library files in the JDK are compiled with debugging information that you’ll need to step into core java classes. Here are the steps to do this:

- Backup the .jar files from JRE_HOME/lib

- Download and install a JDK for the SAME VERSION as your JRE.

- Copy the .jar files from JDK_HOME/jre/lib to JRE_HOME/lib

Once you’ve completed this step, you can launch Eclipse and create a new project. You’ll want to set it up in a similar way to the jar you’re analyzing (in this case, a package called game and all the java sources inside). Here is what mine looked like below.

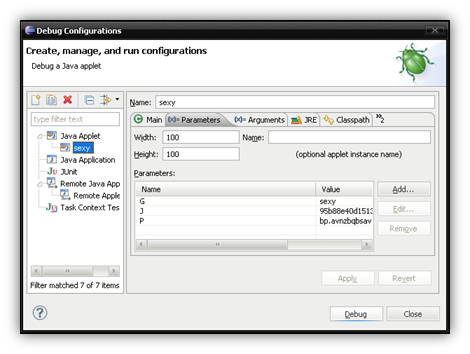

Next you’ll need to build a Debug Configuration for the applet. Make sure that you pay attention to any parameters the applet might need to execute properly (in the case of this jar, there are 3).

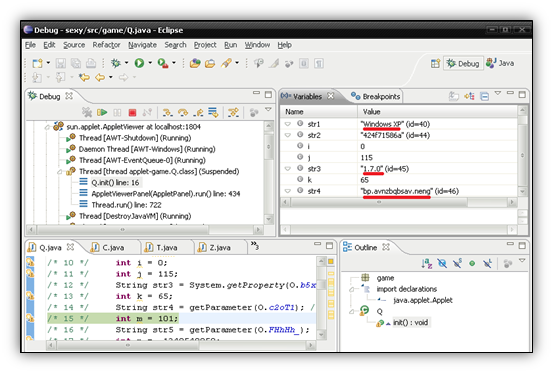

Now you need to set a breakpoint in your code and you can start debugging. Also, you may need to add java source files to your project’s build path if you want to step into java system libraries and observe that code.

Notice how I’ve taken a few steps in the code and already retrieved the OS name, Java version, and some parameters. I can continue to step through the code and terminate the applet when desired.

Conclusion I hope this article gave you a better understanding of the java exploitation landscape.

Understanding how to analyze java code is necessary as the web technology from Oracle continues to be exploited; there’s no doubt we’ll continue to see jars used in malware, as well new techniques like embedded class files and encrypted malware payloads within the jar to keep researchers on their toes.

With some practice and prior programming knowledge, most java code can be understood when viewing decompiled source code. Debugging is always an option too, but the setup time can be lengthy, so it may not be worth the effort in some cases. If you do end up choosing this route, remember to do so in a secure, isolated environment, like a Virtual Machine, to prevent malware infections. When you analyze and execute malware, you do so at your own risk, so take plenty of precautions.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Joshua Cannell is a Malware Intelligence Analyst at Malwarebytes where he performs research and in-depth analysis on current malware threats. He has over 5 years of experience working with US defense intelligence agencies where he analyzed malware and developed defense strategies through reverse engineering techniques. His articles on the Unpacked blog feature the latest news in malware as well as full-length technical analysis. Follow him on Twitter @joshcannell