Recently, I posted a blog about analyzing PDF files. In that post, we covered some basics of the PDF format and then examined an infected PDF to observe the malware infection.

In this post, we’re going to do something similar, except this time using Microsoft Office.

Just like the PDF, most of you reading this are already familiar with Microsoft Office. If you’ve ever had to

type a school paper, for example, you’ve likely used Microsoft Word sometime in your life. Perhaps you took a class on database design, so you may have use Microsoft Access to create and test custom database applications.

In Microsoft Office files, versions 97-03 uses a custom binary file format that is read by the associated Office program.

The technical specification for each format can be quite lengthy; for example, the Word specification (.doc) is over 600 pages long, while Excel (.xls) is at nearly 1200. Changes to these formats came in 2007, however, when Office 2007 debuted with a newer Office Open XML format. The Office Open XML format uses compression with PKZIP and offers an array of enhancements, one being increased security through macro elimination.

However, while you can make the Office file format more secure, Office programs that read these files need to be equally secure in order to be completely safe. The problem, of course, is that they’re not, and that’s why you have instance where older files can still target newer versions of Office.

Let’s get our hands dirty with Office malware by examining an Excel file that demonstrates CVE-2012-0158, aka MSCOMCTL.OCX Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability. The file MSCOMCTL.OCX is the ActiveX common controls DLL for Windows. In this example, the “ListView” and “ListView2” ActiveX controls implemented in the DLL are vulnerable to the exploit, which leads to a malware infection.

For reference purposes, the md5 hash is 0ca16af39749f996df1c499dcda8c269. For our analysis environment, we will be using Office 2007, although other versions of Office are still vulnerable if unpatched, as well as many other applications (refer to CVE description for full list of applications affected).

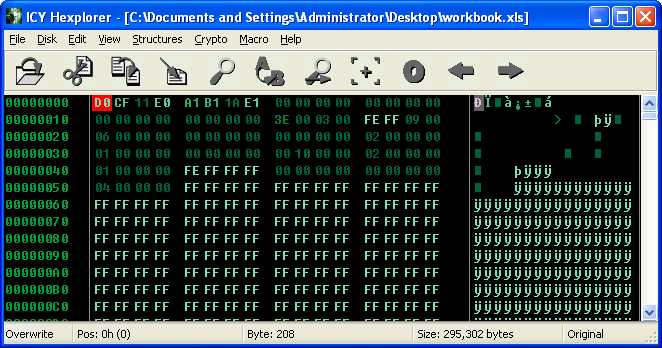

When analyzing a new file (no matter the presumed type) it’s always wise to use a hex editor to observe the headers.

If you notice the first four bytes are D0 CF 11 E0 (“DOCFILE”), which indicate we’re likely dealing with an MS Office file.

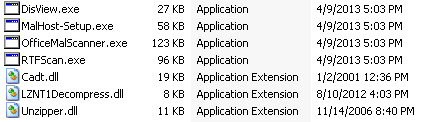

Now we’re going to need some tools. Arguably the best tool for analyzing malicious Office documents is OfficeMalScanner, written by Frank Boldewin. OfficeMalScanner is an “Office forensic tool to scan for malicious traces, like shellcode heuristics, PE-files or embedded OLE streams”.

OfficeMalScanner is a suite of applications and is very good at giving analysts a “lead” on where malicious activity (mostly shellcode) is occurring in the Office document. Let’s observe all the tools OfficeMalScanner gives the user.

OfficeMalScanner.exe is the main binary used to scan office documents for malicious behavior. The program is capable of scanning for shellcode, embedded PE files, OLE streams, and can also disassemble shellcode as well as brute force encrypted bytes (using ADD, XOR, and ROL).

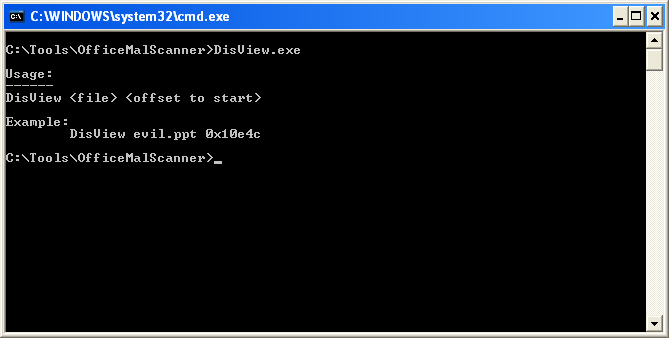

DisView.exe is a command line utility used for disassembling shellcode, starting at a specified offset.

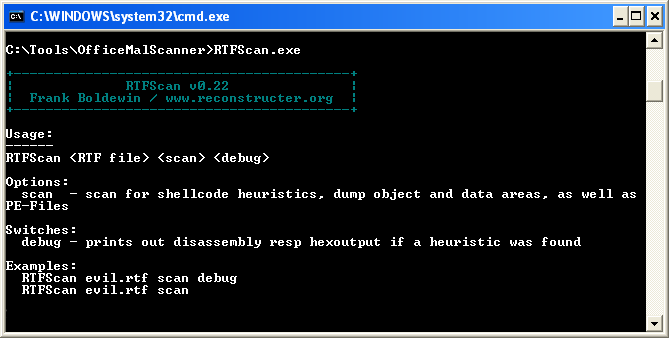

As the name implies, RTFScan.exe scans Rich Text Format (.rtf) files for malicious behavior. The RTF format is another Microsoft proprietary format that can be exploited when used with vulnerable Microsoft Word installations. CVE-2012-0158 can be leveraged against RTF files, and some exploits rely solely on specially crafted RTF files as their vehicle for malware infection (see CVE-2010-3333, aka RTF Stack Buffer Overflow Vulnerability).

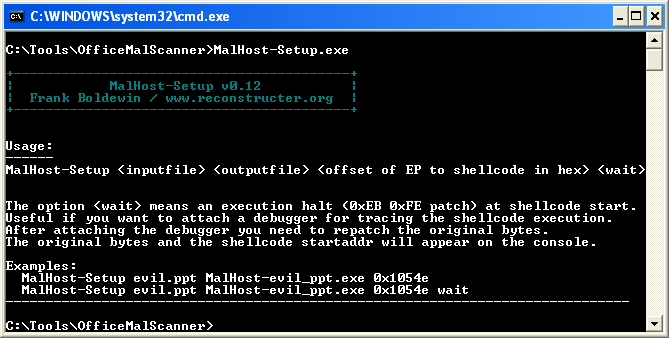

Finally, MalHost-Setup.exe is a tool used to “host” the shellcode embedded in a malicious file. Since Office files execute under the context of their associated Office program, once an exploit occurs, the shellcode runs under the context of that program. MalHost-Setup.exe creates a separate binary to host the embedded shellcode, which can streamline analysis of malicious code.

For example, if I have an infected Excel file and I run it, it gets loaded into the memory address space of Excel’s process, (EXCEL.EXE). However, this can be complicated for analysts and reverse-engineers, as debugging large applications like Excel can be difficult, and it’s nearly impossible to predict where the shellcode will begin executing within the program’s address space. With MalHost-Setup, it’s much easier to run your shellcode in the context of another process that is much more confined.

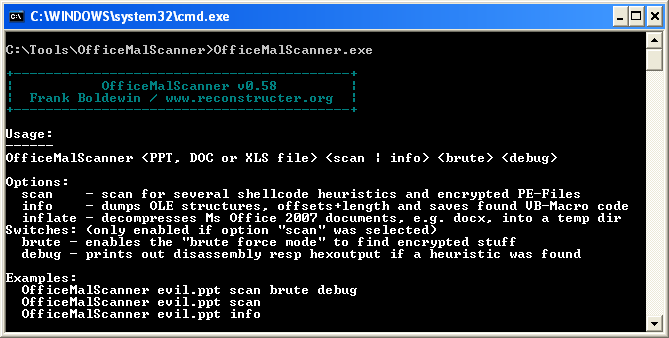

Now that we’ve explained our tools, we can scan the infected Excel file using OfficeMalScanner. If you refer to the picture above, you will notice there are three options—scan, info, and inflate—along with the switches, brute and debug.

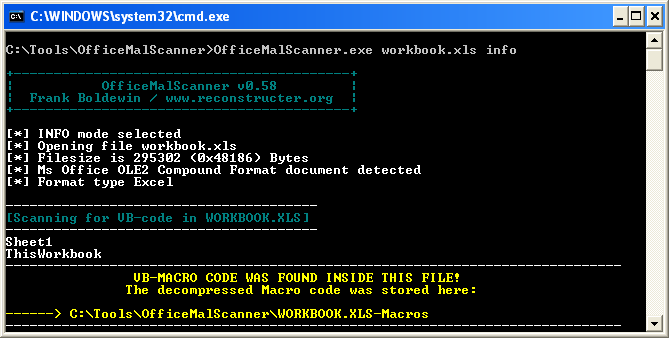

Let’s first try the info option, to look for OLE objects and macro code.

OfficeMalScanner.exe [filename] info

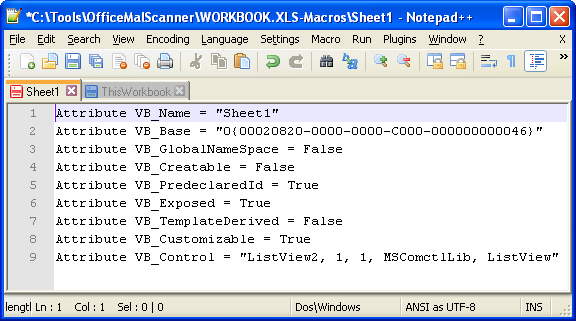

Looks like it found something: VB-Macro code. However, there isn’t anything overtly malicious when observing the produced files, except maybe the presence of the strings “ListView” and “ListView2,” as noted earlier that CVE-2012-0158 documents these ActiveX controls as vulnerable (see full CVE description).

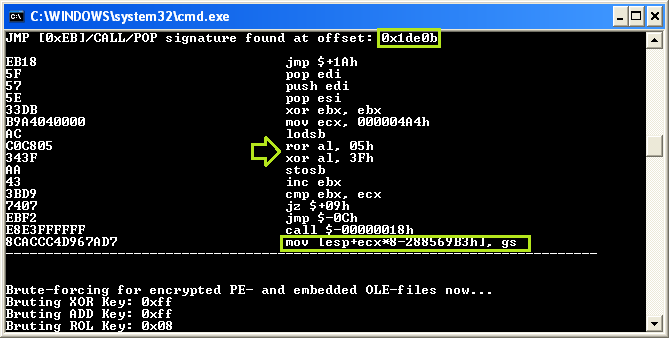

Next we can try the “scan” option, along with the optional switches “brute” and “debug”. When using these two switches, OfficeMalScanner will attempt to disassemble any shellcode detected and use brute force techniques to uncover any encrypted code or files.

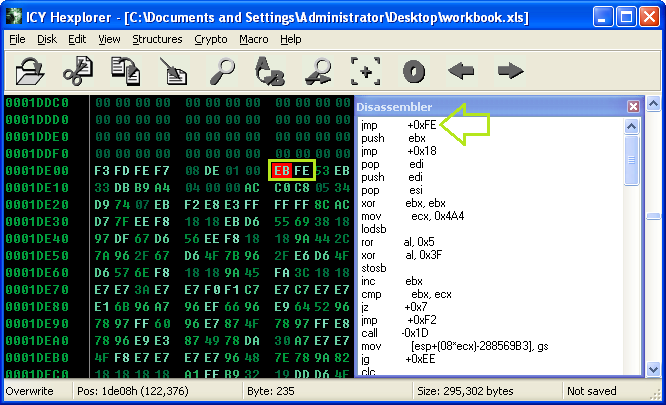

OfficeMalScanner.exe [filename] scan brute debugOfficeMalScanner detected shellcode embedded within the Excel file starting at offset 0x1DE0B. However, some of these instructions don’t seem right, particularly the last instruction: mov [esp+ecx*8-288569B3h], gs. A few instructions prior, though, it can be seen that some bit manipulation is occurring, namely XOR (exclusive or) and ROR (rotate right). This could very well indicate the embedded shellcode performs on-the-fly de-obfuscation as it executes.

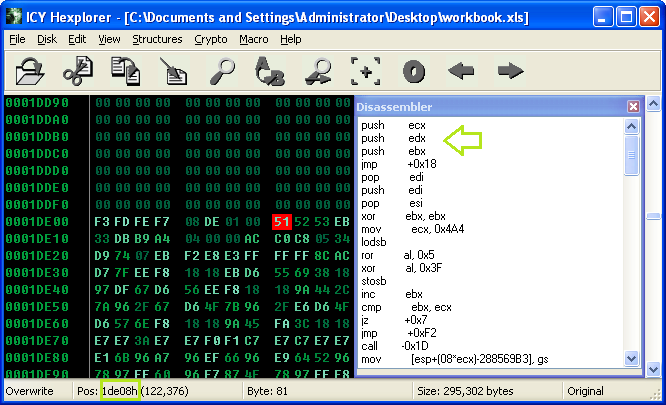

We’re going to need to take a closer look at this shellcode. When loading the file into Hexplorer (or DisView, or anything else that disassembles code), you can analyze the shellcode further. It really seems the code starts at 0x1DE08, starting with a PUSH instruction.

After locating the shellcode, it’s important that we execute this code to see what’s going on, which means we will need to attach a debugger to EXCEL.EXE. However, we just want to go straight to the shellcode, and not mess with Excel and the library files involved, which would waste a lot of time.

One option seems like an obvious solution to our problem: the MalHost-Setup tool. However, when using MalHost-Setup, you’ll eventually get an unhandled exception during execution. This is because the shellcode expects to be running in the context of EXCEL.EXE, and therefore some of the memory offsets don’t match when running under a separate parent process. While tools are always great, none of them are perfect.

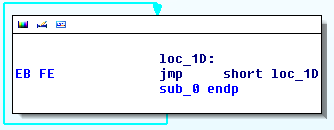

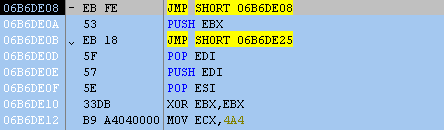

The best way to handle this is to patch a few shellcode bytes. Commonly referred to the “EB FE trick”, this technique will patch two bytes with an infinite loop, allowing us to easily attach a debugger.

In x86 assembly language, the “0xEB” byte indicates a non-conditional jump instruction (JMP), while the second byte, “0xFE” indicates where to jump, which is the next instruction to execute, or EIP register. Refer to the picture below for help understanding this concept (this is a hard one, folks).

Thus an infinite loop is created. Now we need to patch the bytes in our shellcode.

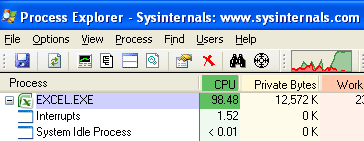

Finally, we can execute the “workbook.xls” file in Excel. You’ll notice that nothing appears to be happening at first—this is because the exploit has occurred and the shellcode has begun to execute, but it’s stuck in the infinite loop we created.

When observing EXCEL.EXE in Process Explorer (or just the regular Task Manager), it can be seen that the infinite loop is causing a lot of CPU usage.

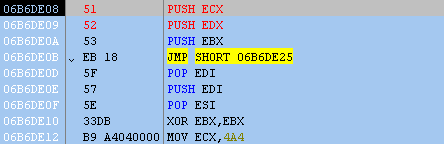

Let’s give our CPU a break and attach to EXCEL.EXE with OllyDbg. Once you attach, resume execution, and then pause again to land at our infinite jump.

While Excel is paused, let’s restore the original bytes (Ctrl + E). Now we can step through the shellcode and see what’s going on.

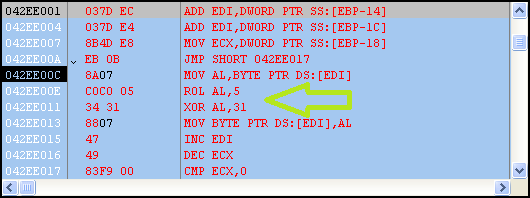

After stepping through a few instructions, it’s easy to see that more code is de-obfuscated on the fly. Each obfuscated byte is placed in the AL register with a ROR 0x5 and XOR 0x3F applied; afterward, the revealed code is executed.

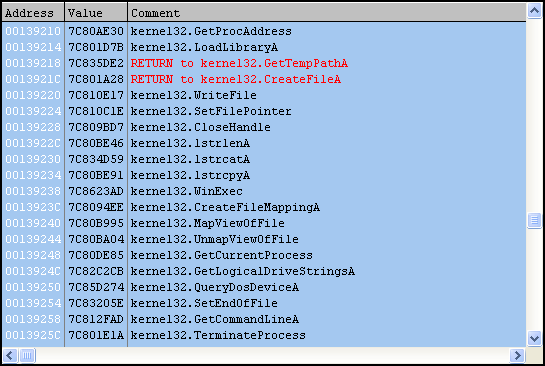

As we continue to step through the shellcode, imported functions are retrieved, which really give us an idea of what’s going to happen next.

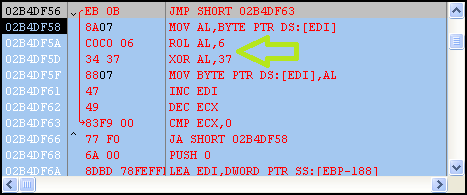

The current user’s temp directory is retrieved (%temp%) and a new file called “set.xls” is created there. Next an embedded Excel file is revealed, obfuscated with a ROL 0x6 and XOR 0x37 applied to each byte.

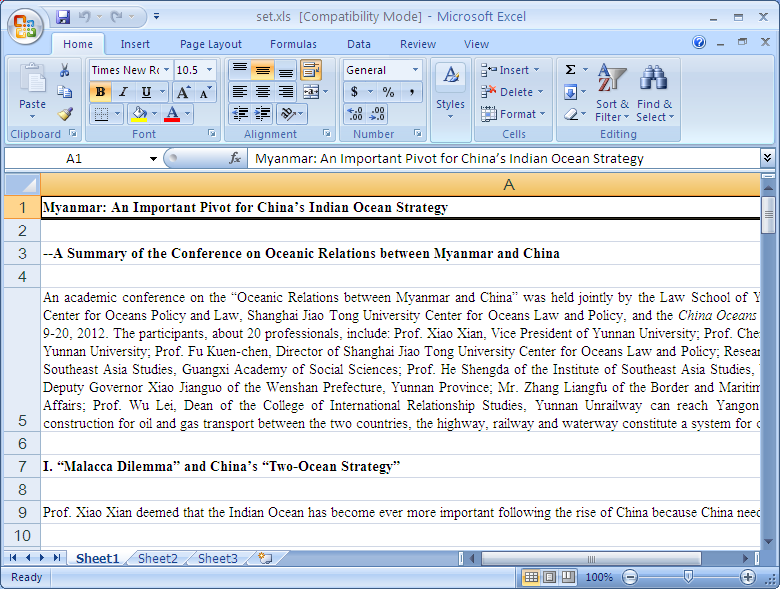

This is a common technique seen in Office malware. The reason this occurs is the exploit typically crashes the host application (EXCEL.EXE in this case) and a new Excel process is created to make it appear the document opened correctly. In this case, that’s exactly what happens, as the file “set.xls” is opened using WinExec. The new file is filled with paragraphs of text to appear legitimate.

Moving on we see yet another de-obfuscation routine, this time the data is applied with ROL 0x5 and XOR 0x31. This shellcode is really a perfect example of why traditional brute force techniques fail, as here we have a) multiple operations performed on each byte and b) multiple values used to obfuscate. Traditional brute force tools usually only factor one value against a stream of bytes, and use one operation at a time (i.e. XOR, AND, etc).

Finally, it appears we’ve made it to the good stuff, an embedded PE file.

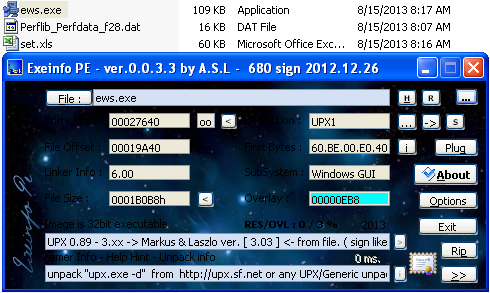

This file will be named “ews.exe” and is also dropped in the current user’s temp directory. Looks like it’s a UPX-packed binary; if we want to analyze from here, we can use the UPX utility with the “-d” command to unpack.

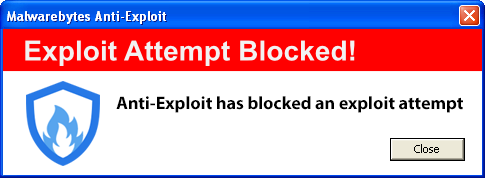

Software exploits are very popular and are responsible for a large majority of malware infections. While it’s most important that you have anti-malware protection to prevent execution of malicious code should an exploit succeed, you might want to consider another layer of defense.

Malwarebytes Anti-Exploit works to stop an exploit before it even starts. The advantage here is that the malware doesn’t get installed and therefore never has a chance to execute.

The program is still in beta, but it currently blocks a wide range of exploits found in the wild, including CVE-2012-0158 (and also CVE-2010-0188, featured in my previous blog post). Should you attempt to open this Excel document with Anti-Exploit installed, the following dialog would appear:

You can download Malwarebytes Anti-Exploit for free here.

Stay tuned for more information from the archives.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Joshua Cannell is a Malware Intelligence Analyst at Malwarebytes where he performs research and in-depth analysis on current malware threats. He has over 5 years of experience working with US defense intelligence agencies where he analyzed malware and developed defense strategies through reverse engineering techniques. His articles on the Unpacked blog feature the latest news in malware as well as full-length technical analysis. Follow him on Twitter @joshcannell