We blogged about the OSX.Backdoor.Eleanor malware that had just been discovered, last week.

In rare turn of events in the Mac world, a new and unrelated piece of malware was announced by ESET the very next day: OSX.Keydnap.

Interestingly, it turns out that this malware could be in some way related to some prominent Windows banking malware.

The Keydnap malware installs via a new twist on an old theme. The “dropper” (the program that installs the malware) comes in the form of a harmless document. Many different forms have been discovered, masquerading as Microsoft Word files, JPEG images and plain text files.

There have been a number of different ways that malware does this, but Keydnap uses a new trick: it puts a space after the extension in the file name. So, for example, what looks like an image file named “logo.jpg” is actually named “logo.jpg “, with a space at the end.

Turns out that space is important. It prevents Mac OS X from seeing the “.jpg” as a file extension, so it doesn’t think the file is actually a JPEG. Since the file is really a Mach-O executable file, double-clicking it will run it in the Terminal, rather than opening a JPEG file as the user would expect.

Once executed, the dropper will install a launch agent to keep a malicious process called icloudsyncd running at all times. It will also download and open a decoy document of some kind, designed to match what the dropper file is pretending to be. Finally, it will quit the Terminal to cover up that it was ever open.

This happens remarkably fast, and at the same time that the decoy is being opened, so the user may not even notice that the Terminal was open.

The icloudsyncd process then communicates with a command & control server via an onion.to address. It can receive a variety of instructions, much like any backdoor, with one interesting exception: it will attempt to capture passwords from the keychain, using the proof-of-concept Keychaindump, and transmit them back to the server.

This means that infected machines may leak all of the passwords stored in the keychain to the criminals behind the malware.

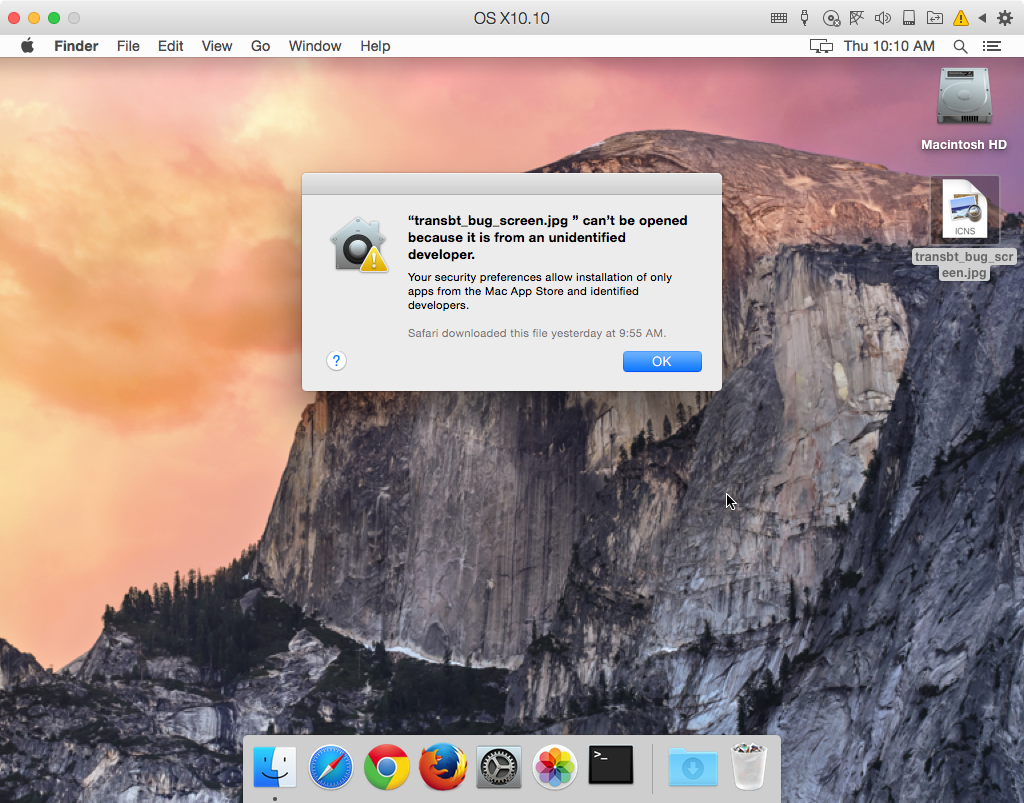

Fortunately, this malware has one significant hurdle to jump to get itself installed: Gatekeeper. By default, Mac OS X will not allow these malicious dropper apps to run, since they aren’t signed with a valid Apple Developer ID certificate.

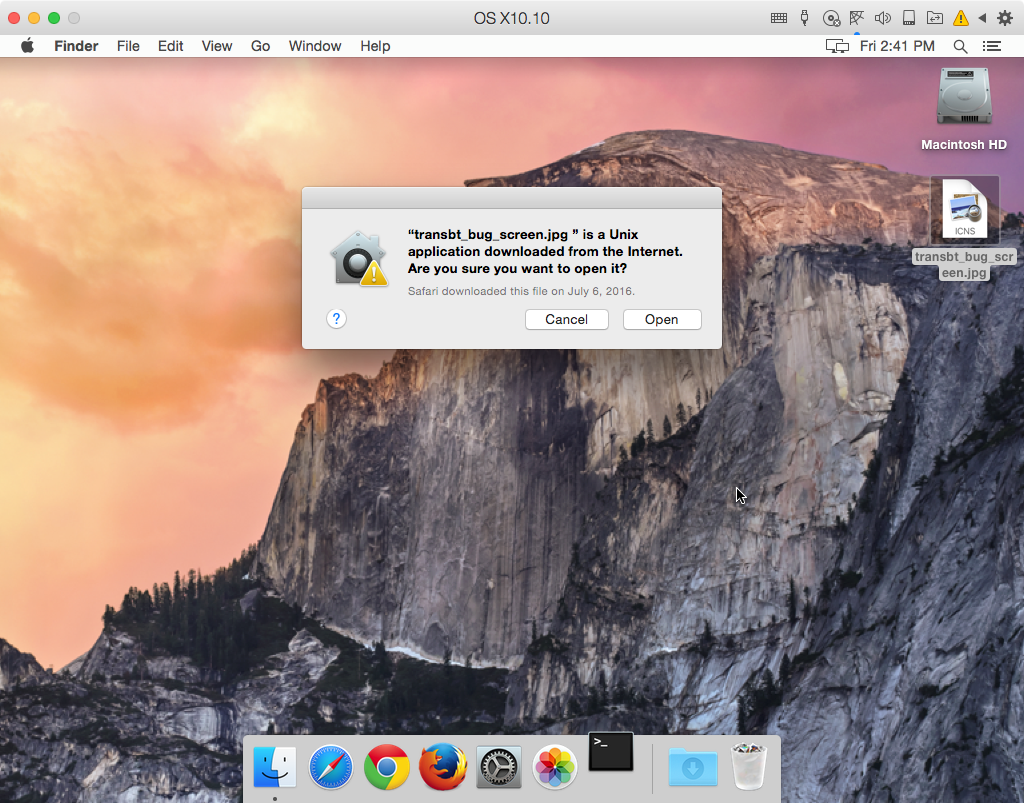

Further, even if the user does have Gatekeeper turned off, they will see a warning that the file is an application downloaded from the internet.

Seeing this when you’re trying to open a JPEG file should be a major red flag. Of course, many people don’t read warnings like this, and will simply click the Open button to make it go away.

In all, this isn’t all that different from other Mac malware that has appeared in the past, except for the theft of keychain data.

A connection to Windows malware

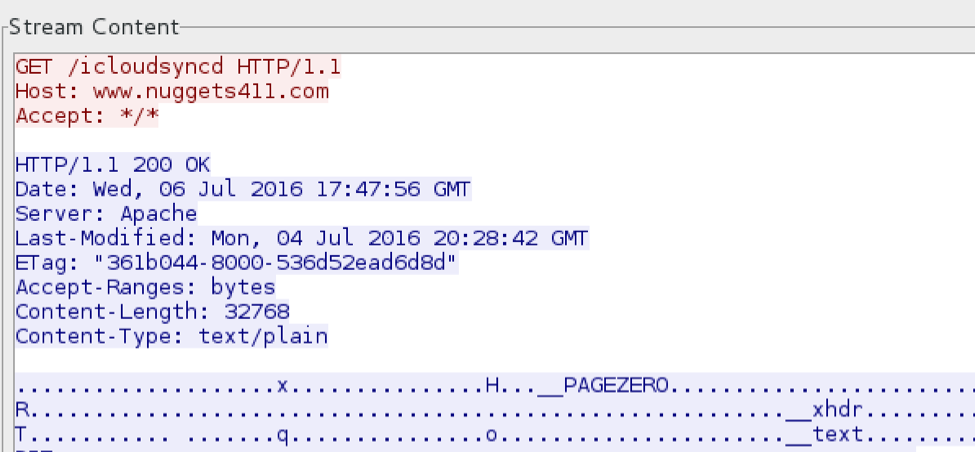

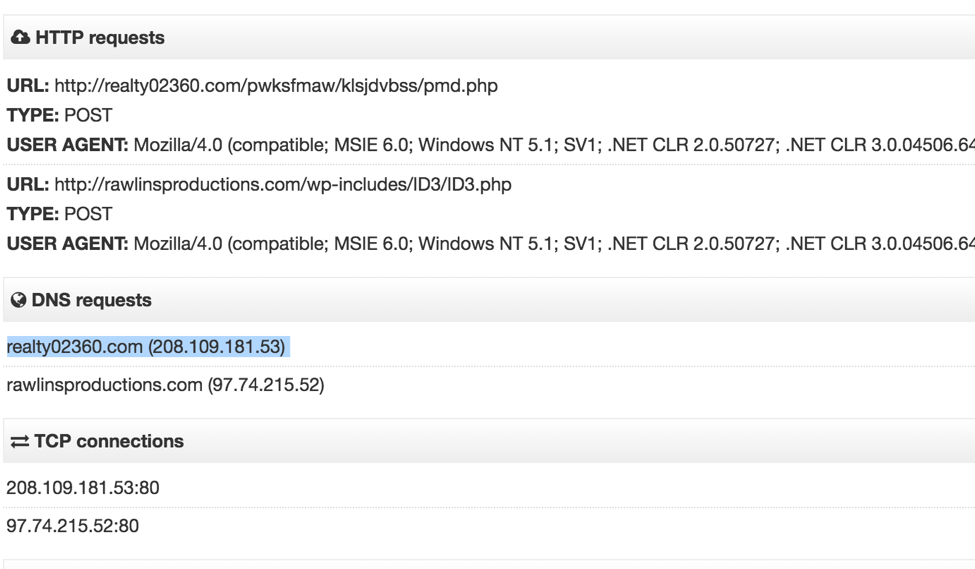

As mentioned, it seems the primary purpose of Keydnap at this time is to snatch and grab credentials from the infected host. It is interesting to note that during our analysis of one variant of Keydnap, we observed the malware downloading its payload from a server which has previously been associated with the popular Windows malware Fareit/Pony. Similar to OSX.Keydnap, one of the main functions of Fareit is the harvesting of credentials from the compromised host.

Host: www.nuggets411[dot]com IP address: 208.109.181.53

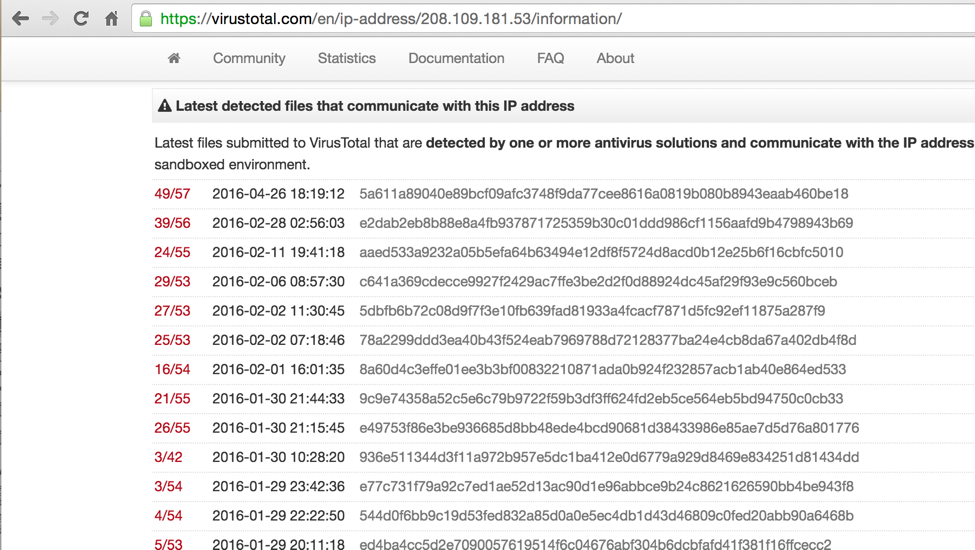

Utilizing VirusTotal to view malware known to communicate with the above IP address yields a multitude of Windows malware including several variants of Fareit:

This particular variant of Fareit, which was distributed in early February 2016, is seen communicating with a similarly named domain to the OSX.Keydnap server and hosted at the same IP address:

Although the codebase doesn’t appear to be the same, nonetheless there seems to be some relationship between Keydnap and Fareit. Although it’s often tempting to think of Mac malware as completely separate from Windows malware, this is not always true. Mac malware like Keydnap may be fairly simple in implementation, but it’s important to keep in mind that the people and infrastructure behind such malware may not be so simple.

(Thanks to Adam Thomas, of Malwarebytes, for the analysis.)