Last time, we took a look at a few common mistakes that are easy to make when trying to attribute cyber attacks. To recap:

Don’t

- Panic over one indicator

- Chase unrealistic threat models (Are you a cleared defense contractor or a law firm servicing one? No? Then APTs are probably not for you.)

- Demand unambiguous data before implementing mitigations. You will not get it, and you will annoy your SOC.

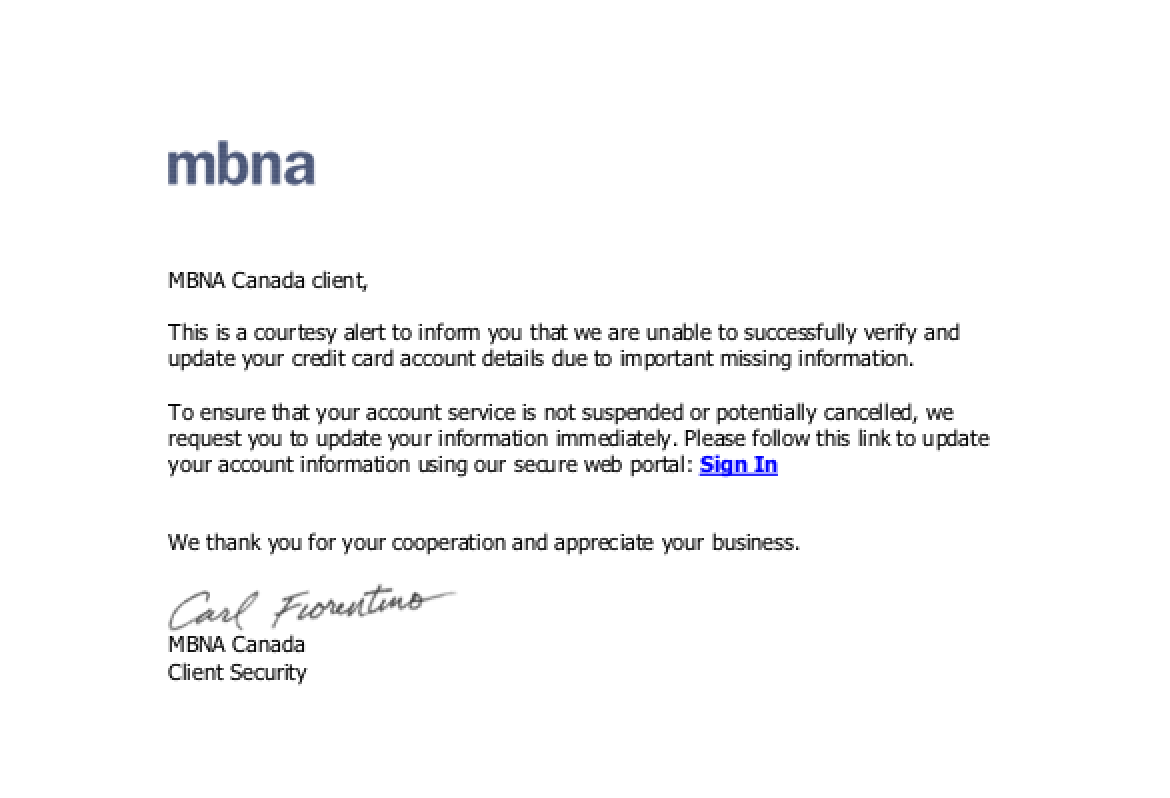

So let us try to see if we can do better. Here’s a banking-themed phish a colleague received back in July.

This is actually pretty decent as banking phishes go. There aren’t any obvious English mistakes tying the content to a specific geographic region*, the language is not hyperbolic, and the signature at the bottom is for a real person. Further, there is no WHOIS data, so the first inclination is to throw up our hands and call it a day. But when we pulled up the landing page, servicesbay[.]ru/server.one (currently down), it has provided a form to enter personal financial information that mirrored MBNA site resources but did not validate user input. Further, the root domain had an open directory leading to other phishes. From an attribution standpoint, we now know a few things:

- The phish was not targeted. No personal victim information appeared on the pitch, and elements of its language could be tracked back to at least 2012.

- The threat actor sophistication is low.

Number two is the tough part, because how can we tell? Incidentals like MBNA not having a “Client Security” division, and “Carl Fiorentino” being a Tiger Direct exec who served 80 months in federal prison for fraud, indicates that our threat actor was disinclined to do his homework. But more telling is the landing page. Landing pages are where the threat actor has one chance to convert user trust and attention into profitable information theft. So the lack of input validation—is this a valid email and credit card, for example—suggests that the threat actor is not really sharp enough to steal efficiently.

We could stop here, if so inclined. Looking at the mechanism of the phish itself, one can form a reasonable belief that it is not targeted specifically to our organization, and the actor is of low sophistication. Those are really the bare bones needed to implement threat mitigations. But let’s take it a little further.

Passive DNS on the landing page has yielded the following (now mostly down):

- Servicechk[.]ru

- Serviceacc[.]ru

- Cs-def[.]ru

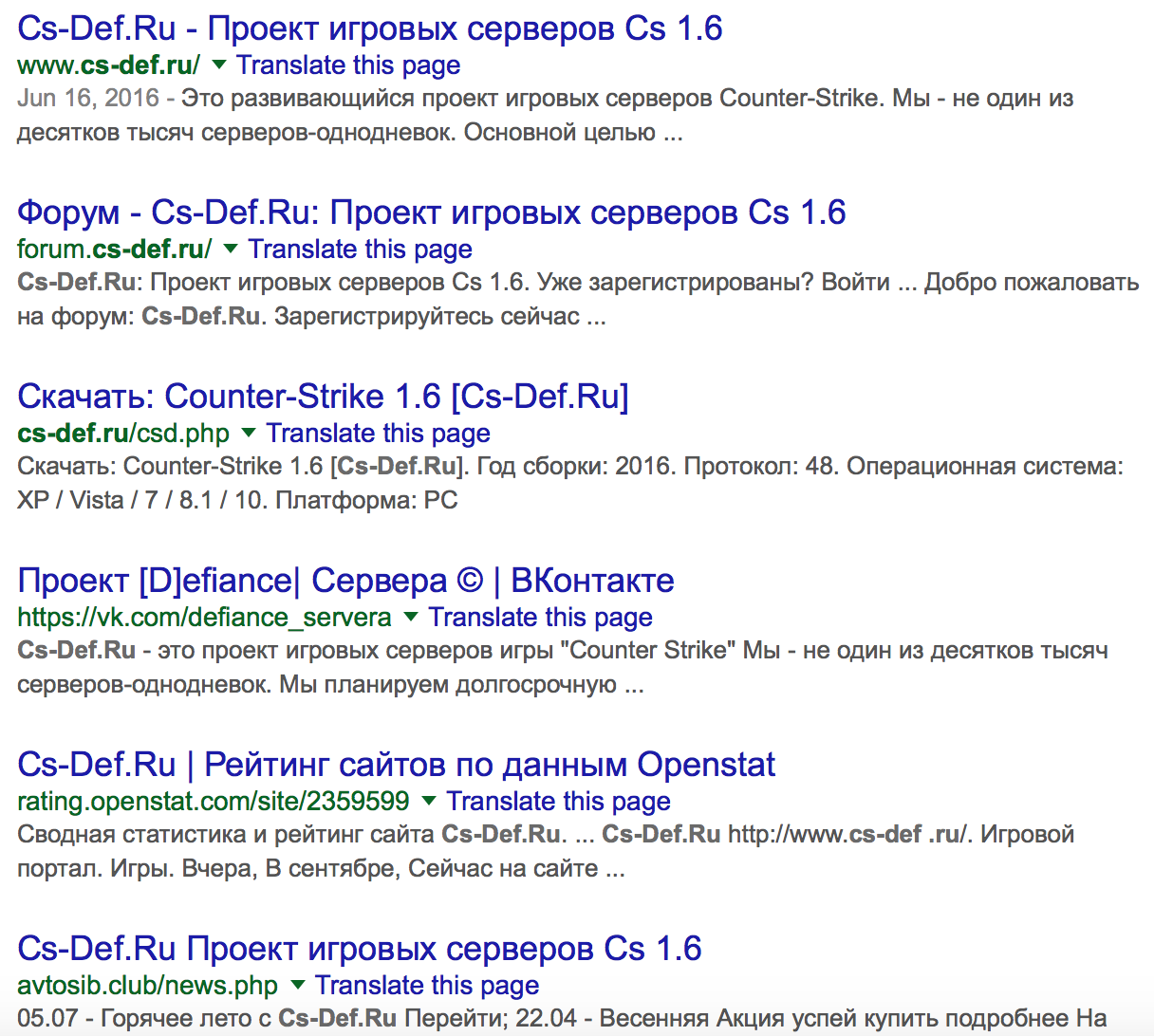

Here we have two sites quite similar to the original landing page, also lacking significant WHOIS, but we can now reasonably say that the phish is hosted by the threat actor, rather than dropped on a compromised benign site. The last site is interesting, as it appears to be a Russian Counterstrike fan page. Given that the phish IP had quite a low number of overall hosts, and fans of online multiplayer games tend to enjoy talking about them online, odds are decent that we might find our threat actor talking about the game. Googling the site itself yields a fair number of hits:

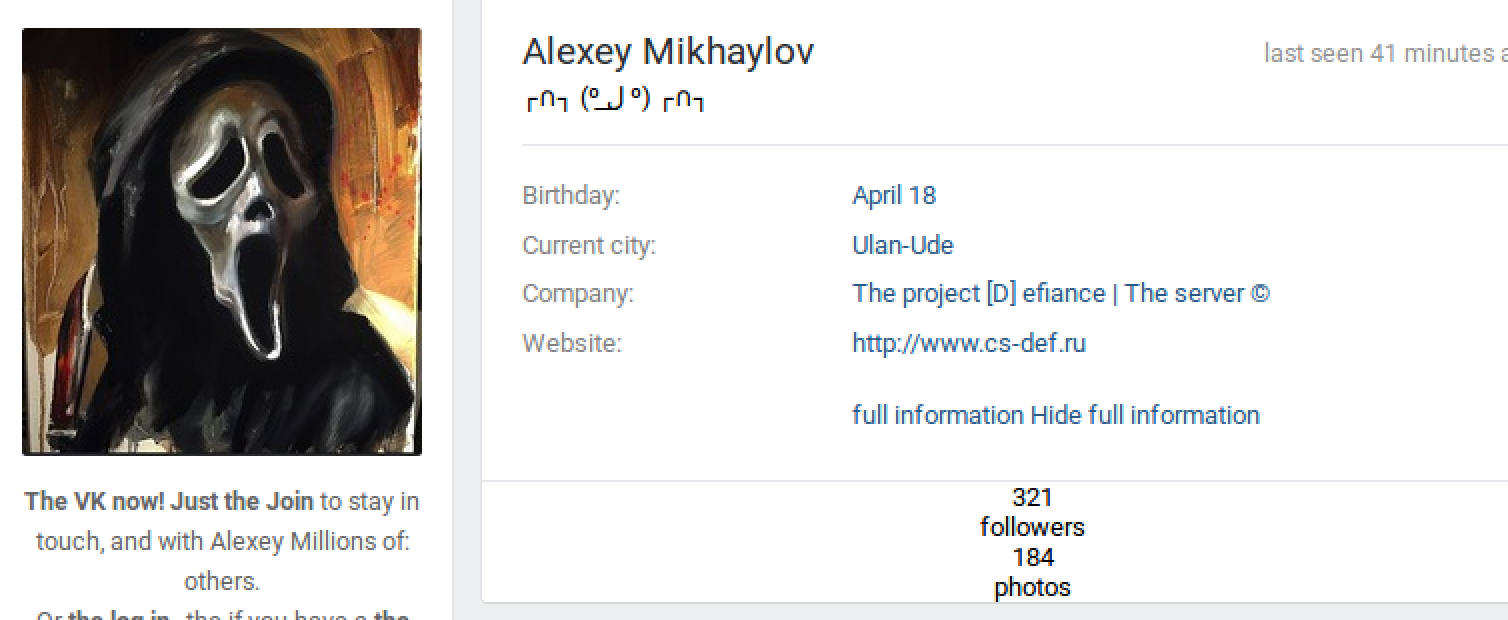

One of those hits is a vk.com profile:

And there we have a name to match our phish. Some caveats:

We have absolutely NOT proven 100% that the above name is behind the phish. Passive DNS does not prove a direct one-to-one link between ownership of multiple websites, even when the overall number of hosts is exceptionally low. Further, we don’t know who the cs-def site owner has given admin credentials to; and lastly, we can’t discount the possibility of a malicious third-party executing a takeover of his infrastructure. However…

We have a reasonable, evidence-backed suspicion that a Russian actor has instigated a generic, low-sophistication phishing wave sent to targets of opportunity.

Given that the above statement is sufficient grounds to make an informed decision on security mitigations, we can consider the attribution complete. Notice that none of the information above is definitive. Alternative Competing Hypotheses can still be applied. The important part is that internal attribution** does not have to be definitive. It has to be reasonable. Should new information alter prior judgement, the attribution should swing back to incomplete and we start the process over.

So we can see using the above example that attribution does not have to be painful, dramatic, or movie-plot ridiculous. At its core, practical cyber threat attribution is about making reasonable judgments against a typically reliable data set in order to drive mitigation decisions. No Pandas, Bears, or three-dimensional matrices required. Tune in next time for Part III: Where Do I Go From Here?

* People go wrong here quite a bit. Amateur language analysis tends to rely heavily on tone, and quantity of mistakes. This is wrong. Rough geographic language typing is done by the quality of mistakes, as second language communicators tend to make English mistakes congruent with the grammar of their native language.

** ALL of your attributions should be internal.