Rootkits are tools and techniques used to hide (potentially malicious) modules from being noticed by system monitoring. Many people, hearing the word “rootkit” directly think of techniques applied in a kernel mode, like IDT (Interrupt Descriptor Table) hooking, SSDT (System Service Dispatch Table) hooking, DKOM (Direct Kernel Object Manipulation), and etc. But rootkits appear also in a simpler, user-mode flavor. They are not as stealthy as kernel-mode, but due to their simplicity of implementation they are much more spread. That’s why it is good to know how they works. In this article, we will have a case study of a simple userland rootkit, that uses a technique of API redirection in order to hide own presence from the popular monitoring tools.

Analyzed sample

01fb4a4280cc3e6af4f2f0f31fa41ef9

//special thanks to @MalwareHunterTeam

The rootkit code

This malware is written in .NET and not obfuscated – it means we can decompile it easily by a decompiler like dnSpy.

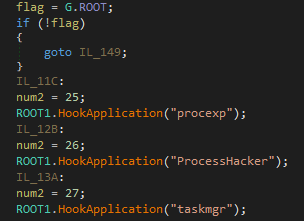

As we can see in the code, it hooks 3 popular monitoring applications: Process Explorer (procexp), ProcessHacker and Windows Task Manager (taskmgr):

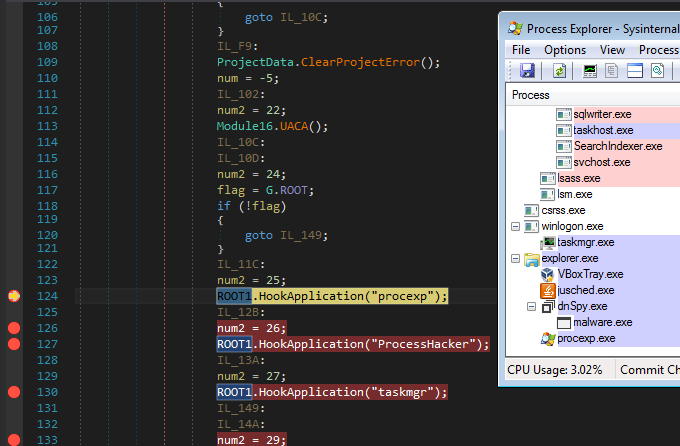

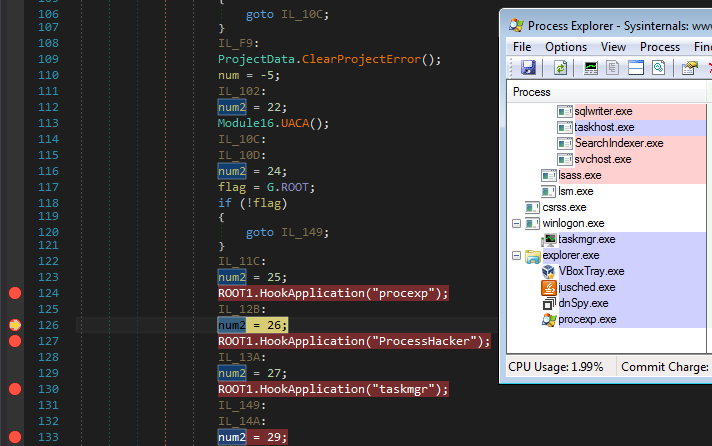

Let’s try to run this malware under dnSpy and observe it’s behavior under Process Explorer. The sample has been named malware.exe. At the beginning it is visible, like any other process:

…but after executing the hooking routine, it just disappears from the list:

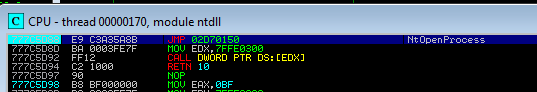

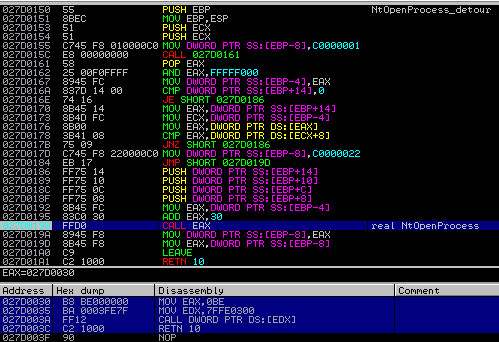

Attaching a debugger to the Process Explorer we can see that some of the API functions, i.e., NtOpenProcess starts in atypical way – from a jump to some different memory page:

The redirection leads to the injected code:

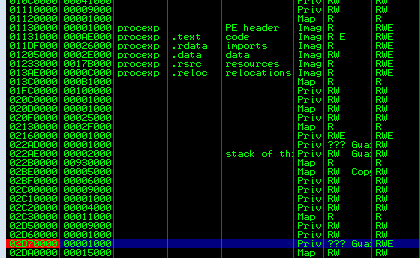

It is placed in added memory page with full access rights:

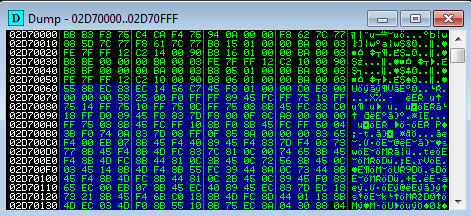

We can dump this page and open it in IDA, getting a view of 3 functions:

The code of the first function begins at offset 0x60:

The space before is filled with some other data, that will be discussed in a second part of the article.

Rootkit implementation

Let’s have a look at the implementation details now. As we saw before, hooking is executed in a function HookApplication.

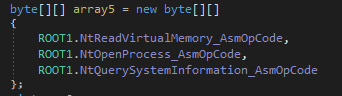

Looking at the beginning of this function we can confirm, that the rootkit’s role is to install in-line hooks on particular API functions: NtReadVirtualMemory, NtOpenProcess, NtQuerySystemInformation. Those functions are imported from ntdll.dll.

Let’s have a look at what is required in order to implement such a simple rootkit.

The original decompiled class is available here: ROOT1.cs.

Preparing the data

First, the malware needs to know the base address, where ntdll.dll is loaded in the space of the attacked process. The base is fetched by a function GetModuleBase address, that employs enumerating through the modules loaded within the examined process (using: Module32First – Module32Next).

Having the module base, the malware needs to know the addresses of the functions, that are going to be overwritten. The GetRemoteProcAddressManual searches those address in the export table of the found module. Fetched addresses are saved in an array:

//fetch addresses of imported functions: func_to_be_hooked[0] = (uint)((int)ROOT1.RemoteGetProcAddressManual(intPtr, (uint)((int)ROOT1.GetModuleBaseAddress(ProcessName, "ntdll.dll")), "NtReadVirtualMemory") ); func_to_be_hooked[1] = (uint)((int)ROOT1.RemoteGetProcAddressManual(intPtr, (uint)((int)ROOT1.GetModuleBaseAddress(ProcessName, "ntdll.dll")), "NtOpenProcess") ); func_to_be_hooked[2] = (uint)((int)ROOT1.RemoteGetProcAddressManual(intPtr, (uint)((int)ROOT1.GetModuleBaseAddress(ProcessName, "ntdll.dll")), "NtQuerySystemInformation") );

Code from the beginning of those functions is being read and stored in buffers:

//copy original functions' code (24 bytes): original_func_code[0] = ROOT1.ReadMemoryByte(intPtr, (IntPtr)((long)((ulong)func_to_be_hooked[0])), 24u); original_func_code[1] = ROOT1.ReadMemoryByte(intPtr, (IntPtr)((long)((ulong)func_to_be_hooked[1])), 24u); original_func_code[2] = ROOT1.ReadMemoryByte(intPtr, (IntPtr)((long)((ulong)func_to_be_hooked[2])), 24u);

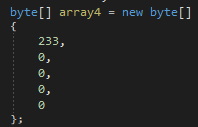

The small 5-byte long array will be used to prepare a jump. The first byte, 233 is 0xE9 hex, and it represents the opcode of the JMP instruction. Other 4 bytes will be filled with the address of the detour function:

Another array contains prepared detours functions in form of shellcodes:

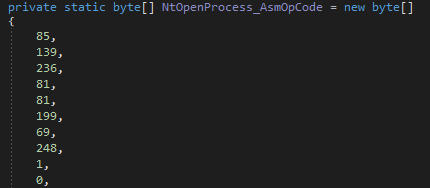

Shellcodes are stored as arrays of decimal numbers:

In order to analyze the details, we can dump each shellcode to a binary form and load it in IDA. For example, the resulting pseudocode of the detour function of NtOpenProcess is:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/40b45481b32dd6ed4c9240a8e1b33795#file-shellcode2-cpp

So, what does this detour function do? Very simple filtering: “if someone ask about the malware, tell them that it’s not there. But if someone ask about something else, tell the truth”.

Other filters, applied on NtReadVirtualMemory and NtQuerySystemInformation (for SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS types: 5 = SystemProcessInformation, 16 = SystemHandleInformation) – manipulates, appropriately: reading memory of the hooked process and reading information about all the processes.

Of course, the fiters must know, how to identify the malicious process that wants to remain hidden. In this rootkit it is identified by the process ID – so, it needs to be fetched and saved in the data that is injected along with the shellcode.

The detour function of NtReadVirtualMemory will also call from inside functions: GetProcessId and GetCurrentProcessId in order to apply filtering – so, their handles need to be fetched and saved as well:

getProcId_ptr = (uint)((int)ROOT1.RemoteGetProcAddressManual(intPtr, (uint)((int)ROOT1.GetModuleBaseAddress(ProcessName, "kernel32.dll")), "GetProcessId") ); getCuttentProcId_ptr = (uint)((int)ROOT1.RemoteGetProcAddressManual(intPtr, (uint)((int)ROOT1.GetModuleBaseAddress(ProcessName, "kernel32.dll")), "GetCurrentProcessId") );

Putting it all together

All the required elements must be put together in a proper way. First, the malware allocates a new memory area, and copies all the elements in order:

BitConverter.GetBytes(getProcId_ptr).CopyTo(array, 0); BitConverter.GetBytes(getCuttentProcId_ptr).CopyTo(array, 4); //... // copy the current process ID BitConverter.GetBytes(Process.GetCurrentProcess().Id).CopyTo(array, 8); //... // copy the original functions' addresses: BitConverter.GetBytes(func_to_be_hooked[0]).CopyTo(array, 12); BitConverter.GetBytes(func_to_be_hooked[1]).CopyTo(array, 16); BitConverter.GetBytes(func_to_be_hooked[2]).CopyTo(array, 20); //... //copy the code of original functions: original_func_code[0].CopyTo(array, 24); original_func_code[1].CopyTo(array, 48); original_func_code[2].CopyTo(array, 72);

After this prolog, the three shellcodes are being copied into the same memory page – and the page is injected into the attacked process.

Finally, the beginning of each attacked function is being patched with a jump, redirecting to the appropriate detour function within the injected page.

Bugs and Limitations

The basic functionality of a rootkit has been achieved here, however, this code contains also some bugs and limitations. For example, it causes an application to crash if the functions have been already hooked (for example in the case if the malware has been deployed for the second time). It is caused by the fact that the hook needs also a copy of the original function in order to work. The hooking function assumes, that the code in the memory of ntdll.dll is always the original one and it copies it to the required buffer (rather than copying it from the raw image of ntdll.dll). Of course this assumption is valid only in optimistic case, and fails if the function was hooked before.

There are also many limitations – i.e.

- the hooking function is deployed only at the beginning of the execution, but when we deploy a monitoring program while the malware is running, we can still see it

- set of hooked applications is small – we can still attach to the malware via debugger or view it by any tool that is not considered by the authors

- the implemented code works only for 32 bit applications

Conclusion

The demonstrated rootkit is very simple, probably created by a novice. However, it allows us to illustrate very well the basic idea behind API hooking and how it can be used in order to hide the process.

This was a guest post written by Hasherezade, an independent researcher and programmer with a strong interest in InfoSec. She loves going in details about malware and sharing threat information with the community. Check her out on Twitter @hasherezade and her personal blog: https://hshrzd.wordpress.com.