Ooh boy! Talk about a back-and-forth, he said, she said story!

No, we’re not talking about that Supreme Court nomination. Rather, we’re talking about Supermicro. Supermicro manufacturers the type of computer hardware that is used by technology behemoths like Amazon and Apple, as well as government operations such as the Department of Defense and CIA facilities. And it was recently reported by Bloomberg that Chinese spies were able to infiltrate nearly 30 US companies by compromising Supermicro—and therefore our country’s technology supply chain.

If you’ve been trying to follow the story, it may feel a bit like this:

What do we know so far

On October 4, Bloomberg Businessweek detailed a narrative regarding Chinese government influence into the operations of US-based hardware manufacturer Super Micro Computer, Inc., or simply Supermicro. The article was produced using information from 17 different anonymous sources including “one from a Chinese foreign ministry,” and draws on research spanning more than three years of investigations.

The article alleges that operatives from a unit of the People’s Liberation Army used a method known as seeding to compromise the Supermicro supply chain. They did this by coercing Chinese-based subcontractors responsible for the creation of the hardware circuitry to secretly install a high-tech spying chip into the motherboards and systems of computers destined for high-profile customers.

Bloomberg suggests the access by top-level operatives allowed the Chinese government to conduct a highly-targeted and highly-complex spying operation against worldwide organizations and in all sectors of business, including finance, health, government, and private.

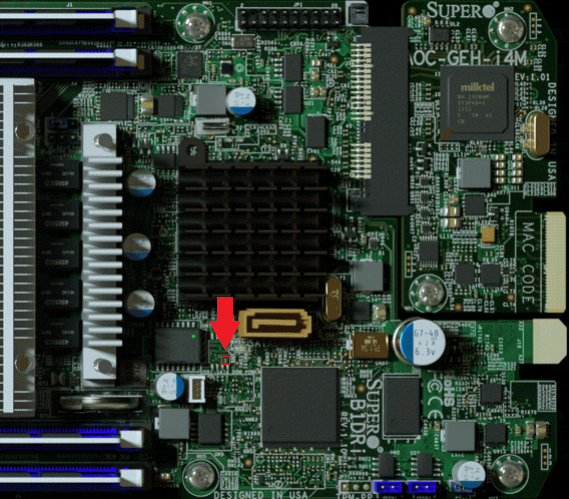

That little chip is what the Bloomberg article says is responsible.

According to the article, the problem stems from a tiny microchip, not any bigger than a pencil tip, and that had been embedded to the electronic circuitry of compromised devices. Though the intent of the microchip remains uncertain, the article suggests it was capable of communicating with anonymous computers on the Internet and loading new code to the device operating system.

In at least one case, the malicious microchips are alleged to be thin enough as to be embedded in between the layers of fiberglass onto which the other components were attached.

The malicious microchip can be embedded between layers of hardware fiberglass.

The chips have the ability of being able to modify the instructions between the operating system and CPU, and can allow for code injection or other data-alteration techniques. The code has also created a stealth doorway into the networks of altered machines.

Or as Bloomberg put it:

The implants on Supermicro hardware manipulated the core operating instructions that tell the server what to do as data move across a motherboard. This happened at a crucial moment, as small bits of the operating system were being stored in the board’s temporary memory en route to the server’s central processor, the CPU. The implant was placed on the board in a way that allowed it to effectively edit this information queue, injecting its own code or altering the order of the instructions the CPU was meant to follow. Deviously small changes could create disastrous effects.

Talk about some deep-state, James Bond–level stuff.

Here, we have a story detailing illicit government operations and covert operatives who have systematically compromised the supply chain of one of the world’s largest motherboard and custom hardware manufacturers. Threat actors have accomplished this using a deeply-technical and highly-targeted—not to mention a nearly impossible mechanism to detect—hardware attack utilizing incredibly small, sophisticated microchips that are embedded between the individual hardware fiberglass layers.

And why did they do it? To initiate clandestine spying operations against some of the worlds’ largest entities in order to exfiltrate sensitive intellectual property and top-secret government information.

Quick, call a Hollywood director. I have a story to pitch!

This is indeed a fantastic story filled with all sorts of nail-biting suspense and adventure, but just like any good Hollywood caper, we have to ask ourselves: Is there any truth to it? We imagine that when storytellers got a whiff of this tale, they did something like this:

Did that really happen?

One problem with verifying this story is that this type of attack isn’t detectable by any security solution. Right now, no one can detect hardware-level modifications using custom hardware solutions that have been systematically installed at the manufacturer level. That kind of detection protocol just doesn’t exist yet.

Another problem: Aside from the S.O.C.-generated network logs pointing fingers at compromised machines and vulnerable networks—for which the article said there were none—no one can prove or disprove this story.

Few security researchers are going to have access to the $100,000+ computers where these chips are said to reside. And even fewer of those researchers work for organizations that will let them start analyzing and ripping capacitor-looking circuits from the board. So basically, we’re left having to trust the anonymous sources used for the report.

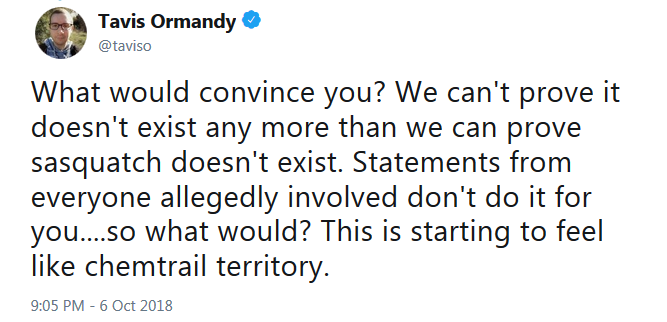

This state of unknown even led well-known Google security researcher Tavis Ormandy to liken the event to the chemtrails conspiracy theory and the hunt for Sasquatch.

In the days since Bloomberg’s publication of the story, there have been significant rebukes and outright denials from the companies and government agencies cited in the report. Here’s what’s been said:

- Amazon called the information untrue and doubled down on the statement by saying it was also untrue it had worked with or provided information to the FBI regarding malicious hardware.

- Apple said they had repeatedly and consistently refuted every aspect of Bloomberg’s story during pre-publication verification efforts, and refute virtually every aspect of the article now.

- Supermicro denied most, if not all, aspects of the Bloomberg story.

- China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicated the government intrusion into the product supply chain would violate China’s commitment to the proposal of the 2011 International Code of Conduct for Information Security.

- And the United States Department of Homeland Security said it had no reason to question denials by US technology companies (though this doesn’t really refute the claims).

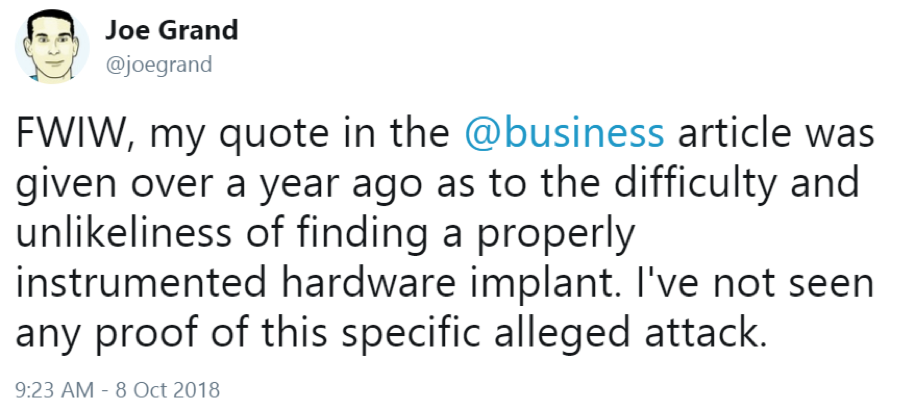

To further muddle the information, the only two named technology experts have backpedaled their statements since publication.

Joe Grand, cited hardware hacker and founder of Grand Idea Studio, Inc., claimed in a recent Twitter post that his quote was given over a year ago and broadly relating to the ultimate story.

In a fascinating podcast on Risky.biz, Joe Fitzpatrick, founder of Hardware Security Resources, expressed concerns regarding the accuracy of the reporting, and claims his statements were taken out of context. In an email exchange provided by Fitzpatrick and read aloud on the Risky.biz podcast, Fitzpatrick expresses skepticism to Bloomberg reporters over the financial cost and scalability of the device.

“The whole setup doesn’t really make sense,” the email is quoted as saying. “It just doesn’t make sense to spend the time and money to do what you are describing. Are you sure that the person who did the analysis had actual hardware knowledge and understanding?” Fitzpatrick concludes, “I’m incredibly skeptical.”

So basically, all of the reporting on this story fell apart post-publication, and everyone involved has denied the aspects of the story. Oops!

Supply chain attacks are real

Even though Bloomberg may (or may not) have got the details wrong on this one, the scenario the story brings up is entirely plausible—though maybe not with the sensationalism portrayed in the article. In fact, supply chain compromises, hardware faults, and outright counterfeits are not at all uncommon. There have been numerous events across the globe that highlight the dangers that audit-free software and single points of failure can introduce.

Just last year, the popular Ukrainian tax software Medoc was subject to a compromised update that went out automatically to millions of customers. The attack resulted in the distribution of the EternalPetya ransomware.

Earlier this year, popular PC cleaner CCleaner was victim of an advanced APT backdoor that came as part of a software supply chain attack. In this multi-thronged attack, threat actors infected 2.27 million users in the first stage. After analyzing the collected information for high-value targets, only 40 were chosen for second-stage attacks and additional espionage efforts. This type of concentrated effort shows the extent attackers are willing to go to infect high-value and potentially lucrative industries and organizations.

Let’s also not forget that Edward Snowden detailed an NSA program that alleged backdoors planted in Cisco products allowed for spying on 20 billion communications each day—or the allegations that the NSA compromised hard drive manufacturers from all over the world to install malware that remained undetected for as long as two decades. Or how Mark Klein detailed secret, unmarked rooms at AT&T from which covert spying operations were being run.

And this doesn’t even touch on the countless vulnerabilities, IOT botnets, default password attacks, or the many other vectors that can be used to launch malware toward systems, peripherals, routers, and other hardware devices we use on a daily basis.

Unfortunately, few of these devices or systems are covered by security solutions that can protect from or remediate the unwanted code and malicious behaviors.

But don’t be fooled. This doom and gloom isn’t just isolated to high-tech computer components and state-sponsored spying. Nor is the problem isolated to components originating from specific geographic regions.

Due to deep supply chains and razor-thin profit margins, consumers face risks every day when at the checkout counter. Consumables can be compromised, either knowingly or not, and with malicious intent or not, in any one of the many downstream transports. This relates to everything from cheap computers and phones purchased from third-party markets all the way down to pet food and lettuce that you buy from your local supermarket. Even the vehicle you drive may have faults attributable to supply-chain issues.

There have been millions of instances where food, phones, computers, manufacturing goods, and virtually every other product known to man have shipped with vulnerabilities or been susceptible to supply-chain tampering.

So what do we do?

Admittedly, that’s a tough nut to crack.

Few in the security industry possess the necessary skills to comprehend—let alone reverse engineer—malicious hardware components that are deliberately designed to look like obscure, legitimate hardware components and are hidden within pin-point modules. And do any of us have the time or desire to understand the inner workings of the devices and systems we purchase? Okay, perhaps a few do.

To make matters worse, there aren’t any security products on the market that have the capability to protect against the sort of sophisticated and targeted attack outlined in the Bloomberg report. To steal a quote from the article: “This stuff is at the cutting edge of the cutting edge, and there is no easy technological solution.”

Regardless of the device or the origin of the product, businesses and consumers alike need to perform due diligence when purchasing devices and products. The risk tolerance may need to be assessed to determine if a particular service or product is worth the potential detriment of losing sensitive information—or other valuable data, time, and peace of mind.

Businesses may wish to conduct hardware security audits on newly-acquired equipment to check for suspicious behavior. IT departments should also consider rolling out updates and patches in staggered succession to monitor for flaws or undesirable effects, thus isolating these problems to a few machines rather than the entire company. And, of course, adopting early technologies should be off-limits for security-conscious enterprises as these products have not yet received the scrutiny of the security community.

How can consumers and businesses truly protect themselves, then? The real answer is “they can’t.” Consumers can never be 100 percent assured the devices and software they buy will be completely harmless.

Without the ability to analyze and reverse-engineer every single device and bit of code that is used, customers have few fail-safe methodologies to ensure their products are free of defect. They must simply research, use common sense, and trust that they’re aligning themselves with products and companies that take the privacy and security of their customers seriously.

Aligning with security best practices, doing due diligence, and conducting a cost/benefit analysis are all good suggestions to follow. But also in this case, maybe crossing your fingers and saying a prayer is just as viable a suggestion.