UPDATE: 4/6/2018

LinkedIn reached out for comment on the article, and we’d like to clarify our position based on their concerns. They wrote:

Members control their connections, who can see them (including keeping them private if they wish) and only first degree connections can get access to your contact info on LinkedIn.

This is correct. LinkedIn visibility controls are clear and easily accessible to the non-technical user. What we were concerned about, however, is the categorization of the connections themselves. Any direct relationship the user instigates is a first degree connection. First degree connections have a predefined level of access that is symmetric, and for the most part, not user editable.

LinkedIn has added a lockdown option that allows you to restrict your viewable connections and email address to not be viewable by anyone. What it lacks are granular permissions on specific data elements assignable to each level of connection.

LinkedIn also informed us that they do, in fact, delete profiles upon request, and provided the following link for more information: https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/63

In the original blog, we claimed otherwise due to referencing a public list of social media deletion practices by a variety of companies. This list turned out to be incorrect.

Lastly, LinkedIn referenced the end user’s ability to control ad targeting preferences. This is also correct. Due to a reference source confusing closing one’s account with deletion of the account, there were concerns regarding data retention practices on a “closed” account. As the reference source was incorrect and LinkedIn does delete accounts after roughly 20 days, our privacy concern is no longer an issue.

______________________________________________________________________________

For users in outward-facing professions like sales or marketing, social media—in particular, LinkedIn—is a highly popular means of connecting to new opportunities in the field and staying current with industry peers.

For the rest of us, LinkedIn is an outstanding means of aggregating personal information without significant safety controls, irritating all your email contacts, and providing an endless stream of phishes, honeytraps, and scams to security personnel.

While many of us do not have the luxury of severing from social media without a second thought, we do think it’s worth knowing what’s happening with your data at LinkedIn and making an informed decision—just as we suggested for users of Facebook confronting the Cambridge Analytica fiasco.

The privacy controls

Originally, LinkedIn started with not much concern for privacy. If you’re on a social media platform, you want to share, right? Well, typically that’s at your discretion, not an algorithm’s (and certainly not one that loves to share indiscriminately).

Today, LinkedIn has done quite a bit better at making their privacy controls accessible and easier to understand, but it still has a few problems baked into the core of the service.

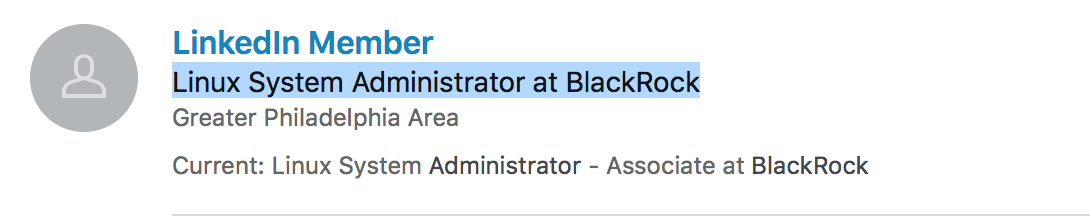

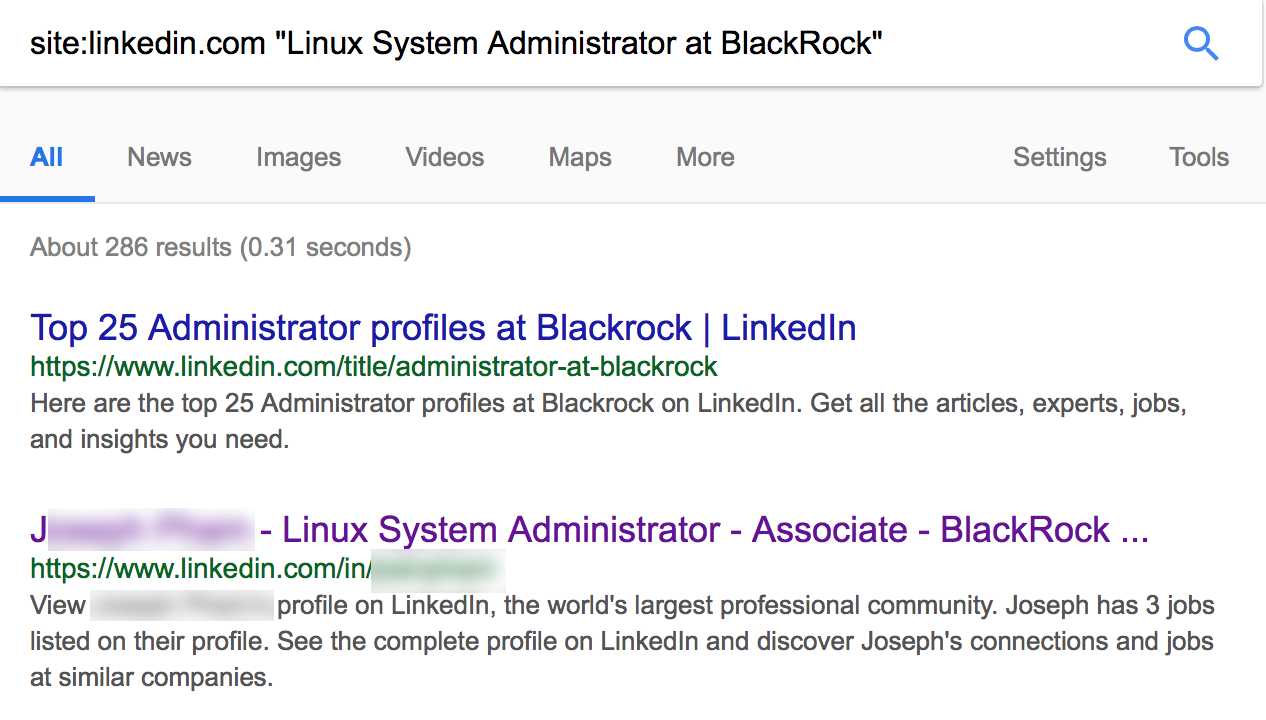

Google indexing

Currently, new profiles default to allow search engine crawlers to access your name, title, current company, and picture. While you can switch that option off easily, if you don’t do it quick enough, that info will be indexed and public, irrespective of any subsequent privacy changes you make.

Searching within Linkedin based on information you get from Google Cache will often yield profiles of people who thought they set their data to private.

Relationship weighting yields increased access automatically

One thing the late, unlamented Google Plus did right is sever symmetric access levels for connections. While you could choose to disclose everything to a connection, the other person wasn’t obligated to do the same to communicate with you.”>

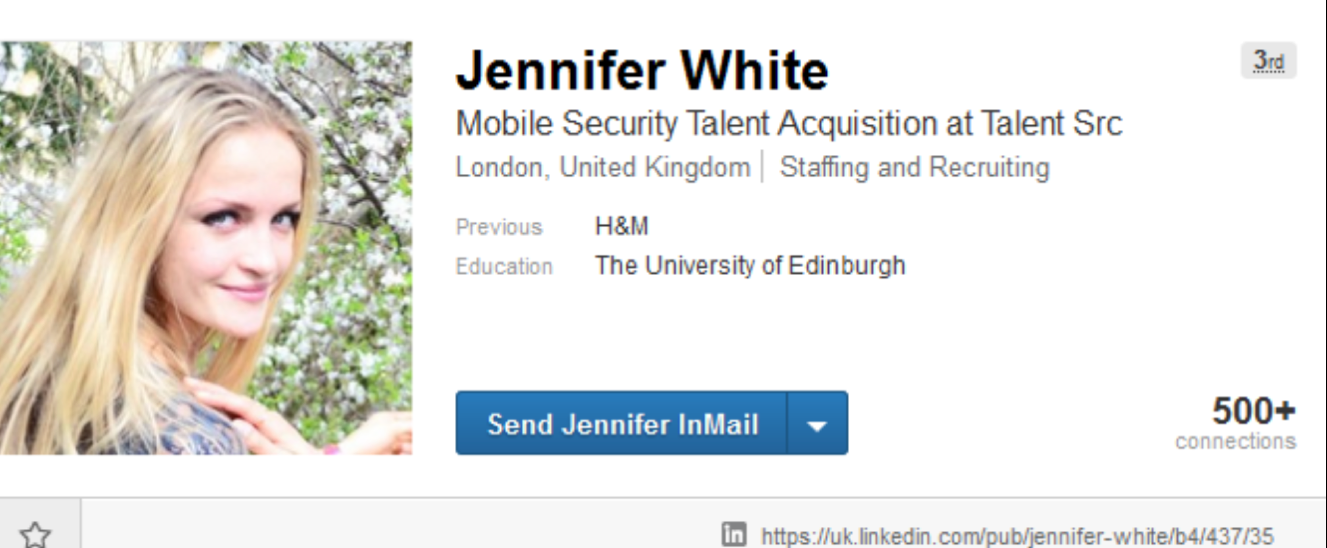

This is not the case with LinkedIn. Reducing trust to a “yes” or “no” question reduces the barrier to entry for information thieves. It’s a trivial matter to observe a target’s position within the network, join their peripheral interests or third-degree connections, then use the automatic increase in access to appear more trusted in a later attack. There really isn’t an effective defense against this sort of social network attack because it depends on every single member of the network being forever vigilant.

Relationship weighting is arbitrary with no user control

LinkedIn has three levels of relationship weighting: first-, second-, and third-degree connections. The end user has no control over who gets which category, and all three categories are based on network proximity.

Why is this a problem? Because relationships aren’t symmetric. You might have a need for a contact’s email without wanting to disclose full info on yourself. However, network proximity weighting presumes equivalence for all contacts in each class. On the contrary, a second-degree connection might be of only occasional interest, while a first-degree connection might have utility for only a limited time.

With cookie cutter policies determining the weight of all of your connections, it robs the end user of setting controls appropriate to each relationship. A great example of this is profile phishing. An attacker only needs to succeed once to become a first-degree connection and gain access to everything.

LinkedIn’s security history

LinkedIn has an extensive history of breaches, vulnerabilities, and personal data leaks for both their web and iOS platforms going back many years. At present, they patch quite quickly upon disclosure, but the slow and steady drip of sometimes serious vulnerabilities over years raises some concerns as to whether or not the platform has a culture of security.

Breaches and vulnerabilities happen to everyone. But if they happen publicly and almost annually, the end user might want to think hard before trusting a third party with their data.

The data hoarding

Like some other third party services, LinkedIn doesn’t delete your account. You can “close” it, but the service retains the right to your information indefinitely. So if you “close” your account, and LinkedIn sustains a breach in the future, your data will be there.

Did you forget to opt out of ad targeting before closing? Your data might still be made available for third-party use. The hallmark of a reasonably secure social media platform is control over your own data, and LinkedIn falls short on this.

But I HAVE to use LinkedIn!

You probably don’t. Unless you belong to the handful of industries for which LinkedIn use is standard, a significant number of opportunities still redirect you toward proprietary recruiting platforms, same as always.

If, however, you absolutely need the service, make sure to log out after each session. Logging out prevents scraping of your network activity, and limits tracking to what you do on the platform. As with most online irritations, ad blockers and anti-tracker extensions can help you keep control of most of your data.

Remember that one of the best defenses against a third-party breach is to think very hard on if you want to trust that third party with your data to begin with. In the case of LinkedIn, the choice is yours. We just want to make sure it’s an informed one.