macOS Mojave was released on Monday, September 24, with much promise of increased privacy protections. In particular, apps are now required to get permission from users before they can access data in certain locations, such as Mail data, contacts, calendar events, Safari user data, and more.

Blocking access to Safari user data would have prevented the issue brought to light earlier this month, in which apps from the Mac App Store were capturing users’ browsing history. In Mojave, unless the user approves an app like Dr. Battery to access that data—which seems unlikely, considering that the app’s purpose had nothing to do with browsing history—the app would be prevented from accessing that data at all.

What’s the problem?

Although the new privacy protections are well-intended, developers and security researchers have expressed some concerns about the way they have been implemented. In particular, there is a legitimate concern about an issue called “dialog fatigue.” The idea is that people get tired of being hassled when they’re trying to get work done, and will just do whatever is needed to click past a warning dialog without actually reading it.

Dialog fatigue—similar to security fatigue—is real, and after having upgraded to Mojave, I can attest to the fact that it has a tendency to display a lot of these dialogs in the beginning. I had to approve access to data for quite a few of my apps. Chances are, the average person will get tired of doing so, and will simply approve each one without paying attention.

To add confusion, these dialogs simply display “Don’t Allow” and “OK” buttons. Although there’s certainly the implication that OK means “allow,” this is not explicitly stated and could result in mistakes being made.

There are also issues with apps that use background processes not triggering the user approval, which can break those apps in interesting ways, such as causing crashes or silently impairing functionality.

Mojave’s privacy protection is far from perfect so far, but it turns out problems go much deeper than user interface issues. Two security researchers have independently, within 24 hours of the Mojave launch, announced troubling findings.

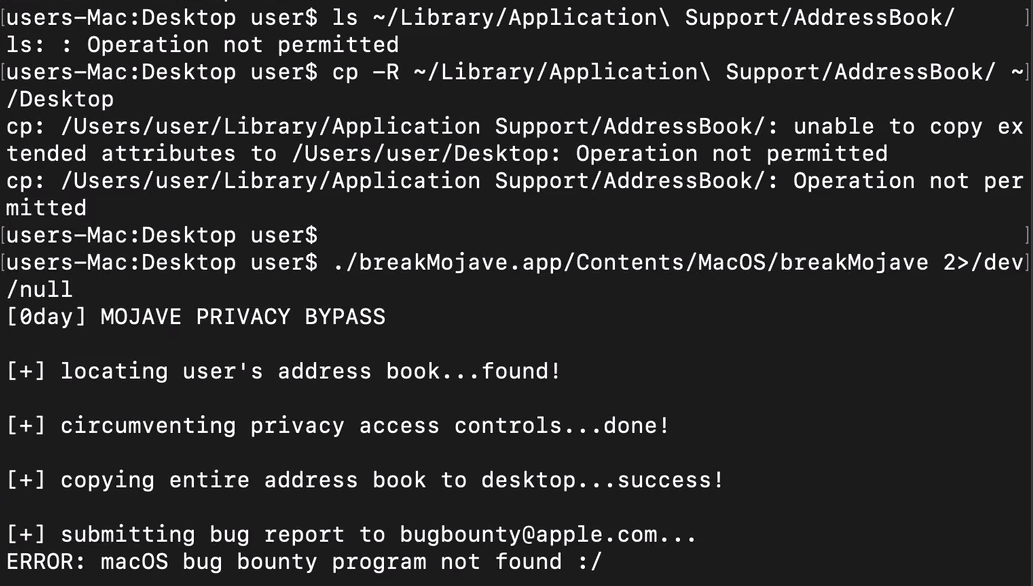

Patrick Wardle posted a video on Monday demonstrating a zero-day vulnerability that can allow a malicious program to gain access to protected data without needing to get the user’s approval. The video demonstrates how to trigger a request for access to contact data in the Terminal, and shows that request being denied. Subsequent attempts to access that data from the Terminal simply fail.

The video then goes on to show execution of a proof-of-concept app Wardle developed, called breakMojave.app. This app does not trigger any access request, and is able to read and copy that data nonetheless.

Wardle has reported this to Apple, but has not made the details of this vulnerability public at this time. He has promised to discuss them at the upcoming Objective by the Sea, the first ever Mac security conference.

The next day, a blog post from a source at SentinelOne revealed that it is possible for a remote attacker to gain access to protected data via ssh.

ssh is a Unix program, and the name is an abbreviation for “secure shell.” The program allows you to establish a remote connection to another computer and send Unix commands through that connection. ssh is often targeted by attackers as a way into a system. And if an attacker can get in via ssh, they can have full control of the machine and access to all data.

SentinelOne goes on to point out that many different processes will be highly likely to be given full disk access. For example, the Terminal can be used to access many different parts of the disk, and may be given a global exemption by power users. People who run AppleScripts are likely to give access to programs like System Events, Script Editor, or Automator. Any of these could be hijacked to execute malicious commands.

What does this mean?

As far as actual risk, you’re no worse off in Mojave than you were running any older version of macOS, none of which featured this kind of privacy protection. In fact, despite these bugs, it’s still harder for an app to get access to this data than it was before.

However, these changes continue a troubling trend at Apple. macOS High Sierra began a concerning process of causing significant problems for developers and users alike, via the user approval process for installing kernel extensions. There are many issues in that process involving both the user experience and bugs in macOS. The user ends up confused and frustrated, and the developer ends up working as unpaid Apple support.

The explosion of new approval dialogs produced by these changes to Mojave will be another step down this same road. The friction people experience with these dialogs will result in developers being penalized for doing interesting and innovative things, while many users will continue to click “OK” in warning dialogs without reading them.

Protecting the user’s privacy is an extremely noble goal, but the multiple issues and bugs involved with this particular implementation will likely cause more problems in the short term than they will solve.