Sarah* hovered over the mailbox, envelope in hand. She knew as soon as she mailed off her DNA sample, there’d be no turning back. She ran through the information she looked up on 23andMe’s website one more time: the privacy policy, the research parameters, the option to learn about potential health risks, the warning that the findings could have a dramatic impact on her life.

She paused, instinctively retracting her arm from the mailbox opening. Would she live to regret this choice? What could she learn about her family, herself that she may not want to know? How safe did she really feel giving her genetic information away to be studied, shared with others, or even experimented with?

Thinking back to her sign-up experience, Sarah suddenly worried about the massive amount of personally identifiable information she already handed over to the company. With a background in IT, she knew what a juicy target hers and other customers’ data would be for a potential hacker. Realistically, how safe was her data from a potential breach? She tried to recall the specifics of the EULA, but the wall of legalese text melted before her memory.

Pivoting on her heel, Sarah began to turn away from the mailbox when she remembered just why she wanted to sign up for genetic testing in the first place. She was compelled to learn about her own health history after finding out she had a rare genetic disorder, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and wanted to present her DNA for the purpose of further research. In addition, she was on a mission to find her mother’s father. She had a vague idea of who he was, but no clue how to track him down, and believed DNA testing could lead her in the right direction.

Sarah closed her eyes and pictured her mother’s face when she told her she found her dad. With renewed conviction, she dropped the envelope in the mailbox. It was done.

*Not her real name. Subject asked that her name be changed to protect her anonymity.

An informed decision

What if Sarah were you? Would you be inclined to test your DNA to find out about your heritage, your potential health risks, or discover long lost family members? Would you want to submit a sample of genetic material for the purpose of testing and research? Would you care to have a trove of personal data stored in a large database alongside millions of other customers? And would you worry about what could be done with that data and genetic sample, both legally and illegally?

Perhaps your curiosity is powerful enough to sign up without thinking through the consequences. But this would be a dire mistake. Sarah spent a long time weighing the pros and cons of her situation, and ultimately made an informed decision about what to do with her data. But even she was missing parts of the puzzle before taking the plunge. DNA testing is so commonplace now that we’re blindly participating without truly understanding the implications.

And there are many. From privacy concerns to law enforcement controversies to life insurance accessibility to employment discrimination, red flags abound. And yet, this fledgling industry shows no signs of stopping. As of 2017, an estimated 12 million people have had their DNA analyzed through at-home genealogy tests. Want to venture a guess at how many of those read through the 21-page privacy policy to understand exactly how their data is being used, shared, and protected?

Nowadays, security and privacy cannot be assumed. Between hacks of major social media companies and underhanded sharing of data with third parties, there are ways that companies are both negligent of the dangers of storing data without following best security practices and complicit in the dissemination of data to those willing to pay—whether that’s in the name of research or not.

So I decided to dig into exactly what these at-home DNA testing kit companies are doing to protect their customers’ most precious data, since you can’t get much more personally identifiable than a DNA sample. How seriously are these organizations taking the security of their data? What is being done to secure these massive databases of DNA and other PII? How transparent are these companies with their customers about what’s being done with their data?

There’s a lot to unpack with commercial DNA testing—often pages and pages of documents to sift through regarding privacy, security, and design. It can be mind-numbingly difficult to process, which is why so many customers just breeze through agreements and click “Okay” without really thinking about what they’re purchasing.

But this isn’t some app on your phone or software on your computer. It’s data that could be potentially life-changing. Data that, if misinterpreted, could send people into an emotional tailspin, or worse, a false sense of security. And it’s data that, in the wrong hands, could be used for devastating purposes.

In an effort to better educate users about the pros and cons of participating in at-home DNA testing, I’m going to peel back the layers so customers can see for themselves, as clearly as possible, the areas of concern, as well as the benefits of using this technology. That way, users can make informed choices about their DNA and related data, information that we believe should not be taken or given away lightly.

That way, when it’s your turn to stand in front of the mailbox, you won’t be second-guessing your decision.

Area of concern: life insurance

Only a few years ago in the United States, health insurance companies could deny applicants coverage based on pre-existing conditions. While this is thankfully no longer the case, life insurance companies can be more selective about who they cover and how much they charge.

According to the American Counsel for Life Insurers (ACLI), a life insurance company may ask an applicant for any relevant information about his health—and that includes the results of a genetic test, if one was taken. Any indication of health risk could factor into the price tag of coverage here in the United States.

Of course, there’s nothing that forces an individual to disclose that information when applying for life insurance. But the industry relies on honest communication from its customers in order to effectively price policies.

“The basis of sound underwriting has always been the sharing of information between the applicant and the insurer—and that remains today,” said Dr. Robert Gleeson, consultant for the ACLI. “It only makes sense for companies to know what the applicant knows. There must be a level playing field.”

The ACLI believes that the introduction of genetic testing can actually help life insurers better determine risk classification, enabling them to offer overall lower premiums for consumers. However, the fact remains: If a patience receives a diagnosis or if genetic testing reveals a high risk for a particular disease, their insurance premiums go up.

In Australia, any genetic results deemed a health risk can result in not only increased premiums but denial of coverage altogether. And if you thought Australians could get away with a little white lie of omission when applying for life insurance, they are bound by law to disclose any known genetic test results, including those from at-home DNA testing kits.

Area of concern: employment

Going back as far as 1964 to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, employers cannot discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, or nationality. Workers with disabilities or other health conditions are protected by the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Rehab Act, and the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

But these regulations only apply to employees or candidates with a demonstrated health condition or disability. What if genetic tests reveal the potential for disability or health concern? For that, we have GINA.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) prohibits the use of genetic information in making employment decisions.

“Genetic information is protected under GINA, and cannot be considered unless it relates to a legitimate safety-sensitive job function,” said John Jernigan, People and Culture Operations Director at Malwarebytes.

So that’s what the law says. What happens in reality might be a different story. Unfortunately, it’s popular practice for individuals to share their genetic results online, especially on social media. In fact, 23andMe has even sponsored celebrities unveiling and sharing their results. Surely no one will see videos of stars like Mayim Bialik sharing their 23andMe results live and follow suit.

The hiring process is incredibly subjective. It would be almost impossible to point the finger at any employer and say, “You didn’t hire me because of the screenshot I shared on Facebook of my 23andMe results!” It could be entirely possible that the candidate was discriminated against, but in court, any he said/she said arguments will benefit the employer and not the employee.

Our advice: steer clear of sharing the results, especially any screenshots, on social media. You never know how someone could use that information against you.

Area of concern: personally identifiable information (PII)

Consumer DNA tests are clearly best known for collecting and analyzing DNA. However just as important—arguably more so to their bottom line—is the personally identifiable information they collect from their customers at various points in their relationship. Organizations are absorbing as much as they can about their customers in the name of research, yes, but also in the name of profit.

What exactly do these companies ask for? Besides the actual DNA sample, they collect and store content from the moment of registration, including your name, credit card, address, email, username and password, and payment methods. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

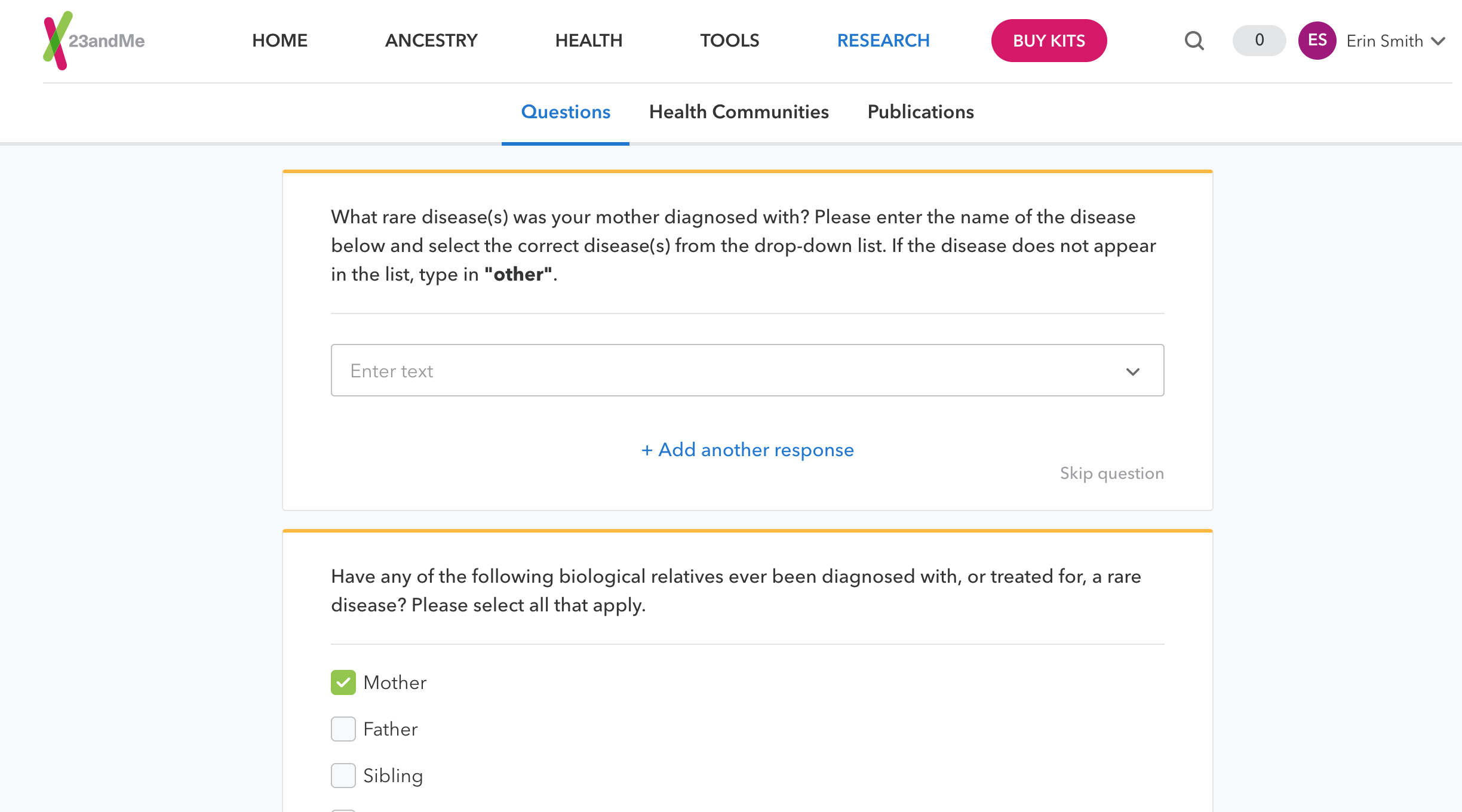

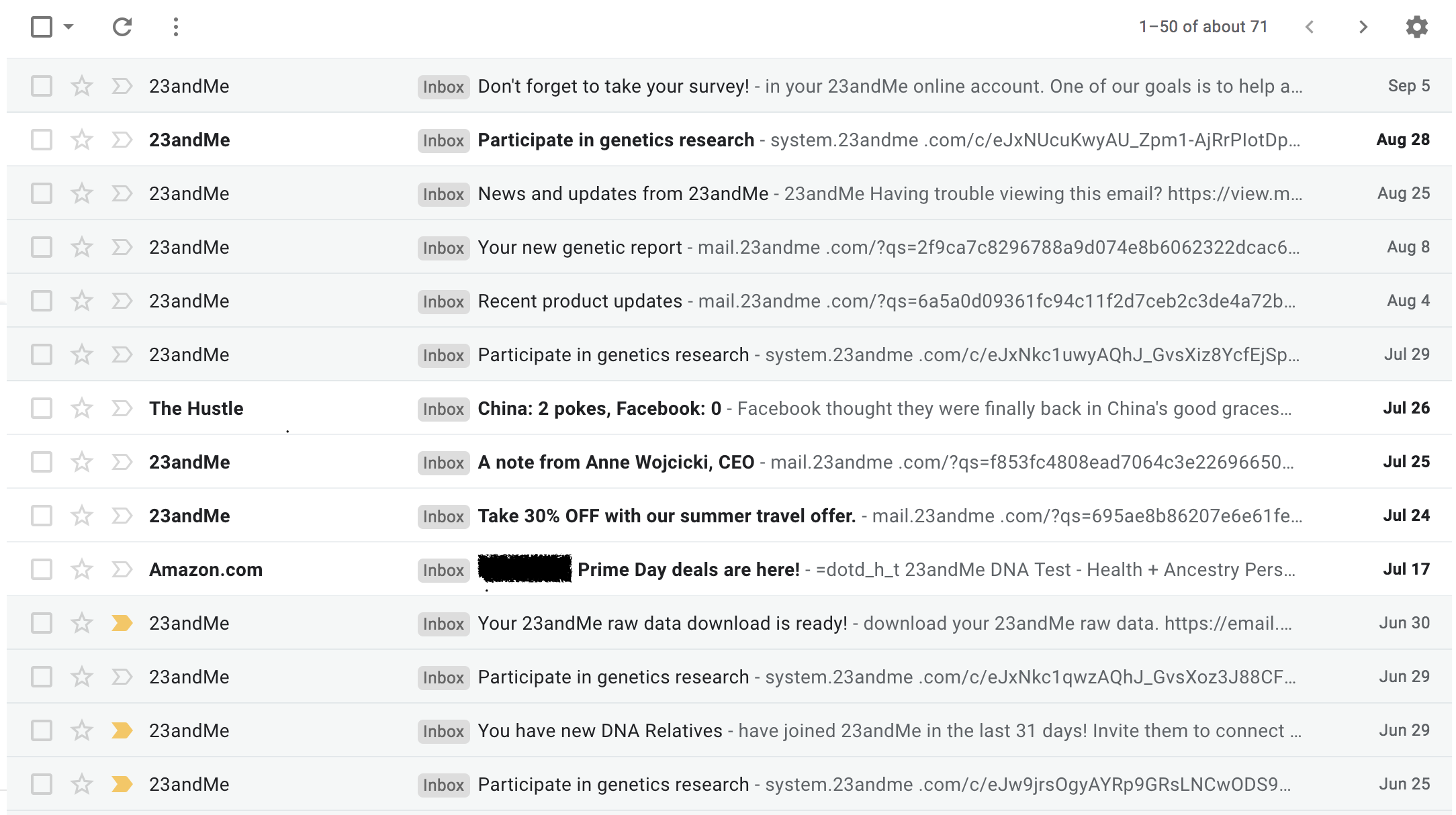

Along with the genetic and registration data, 23andMe also curates self-reported content through a hulking, 45-minute long survey delivered to its customers. This includes asking about disease conditions, medical and family history, personal traits, and ethnicity. 23andMe also tracks your web behavior via cookies, and stores your IP address, browser preference, and which pages you click on. Finally, any data you produce or share on its website, such as text, music, audio, video, images, and messages to other members, belongs to 23andMe. Getting uncomfortable yet? These are hugely attractive targets for cybercriminals.

Survey questions gather loads of sensitive PII.

Oh, but there’s more. Companies such as Ancestry or Helix have ways to keep their customers consistently involved with their data on their sites. They’ll send customers a message saying, “You disclosed to us you had allergies. We’re doing this study on allergies—can you answer these questions?” And thus even more information is gathered.

Taking a closer look at the companies’ EULAs, you’ll discover that PII can also be gathered from social media, including any likes, tweets, pins, or follow links, as well as any profile information from Facebook if you use it to log into their web portals.

But the information-gathering doesn’t stop there. Ancestry and others will also search public and historical records, such as newspaper mentions, birth, death, and marriage records related to you. In addition, Ancestry cites a frustratingly vague “information collected from third parties” bullet point in their privacy policy. Make of that what you will.

Speaking of third parties, many of them will get a good glimpse of who you are thanks to policies that allow for commercial DNA testing companies to market new products offers from business partners, including producing targeted ads personalized to users based on their interests. And finally, according to the privacy policy shared among many of these sites, DNA testing companies can and do sell your aggregate information to third parties “in order to perform business development, initiate research, send you marketing emails, and improve our services.”

That’s a lot of marketing emails.

One such partner who benefits from the sharing of aggregate information is Big Pharma: at-home DNA testing kits profit by selling user data to pharmaceutical companies for development of new drugs. For some, this might constitute crossing the line; for others, it represents being able to help researchers and those suffering from disease with their data.

“You have to trust all their affiliates, all their employees, all the people that could purchase the company,” said Sarah, our IT girl who elected to participate in 23andMe’s research. “It’s better to take the mindset that there’s potential that any time this could be seen and accessed by anyone. You should always be willing to accept that risk.”

Sadly, there’s already more than enough reason to assume any of this information could be stolen—because it has.

In June 2018, MyHeritage announced that the data of over 92 million users was leaked from the company’s website in October the previous year. Emails and hashed passwords were stolen—thankfully, the DNA and other data of customers was safe. Prior to that, the emails and passwords of 300,000 users from Ancestry.com were stolen back in 2015.

But as these databases grow and more information is gathered on individuals, the mark only becomes juicier for threat actors. “They want to create as broad a profile of the target as possible, not just of the individual but of their associates,” said security expert and founder of Have I Been Pwned Troy Hunt, who tipped off Ancestry about their breach. “If I know who someone’s mother, father, sister, and descendants might be, imagine how convincing a phishing email I could create. Imagine how I could fool your bank.”

Cybercriminals can weaponize data not only to resell to third parties but for blackmail and extortion purposes. Through breaching this data, criminals could dangle coveted genetic, health, and ancestral discoveries in front of their victims. You’ve got a sibling—send money here and we’ll show you who. You’re pre-dispositioned to a disease, but we won’t tell you which one until you send Bitcoin here. Years later, the Ashley Madison breach is still being exploited in this way.

Doing it right: data stored safely and separately

With so much sensitive data being collected by DNA testing companies, especially content related to health, one would hope these organizations pay special attention to securing it. In this area, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that several of the top consumer DNA tests banded together to create a robust security policy that aims to protect user data according to best practices.

And what are those practices? For starters, DNA testing kit companies store user PII and genetic data in physically separating computing environments, and encrypt the data at rest and in transit. PII is assigned a randomized customer identification number for identification and customer support services, and genetic information is only identified using a barcode system.

Security is baked into the design of the systems that gather, store, and disseminate data, including explicit security reviews in the software development lifecycle, quality assurance testing, and operational deployment. Security controls are also audited on a regular basis.

Access to the data is restricted to authorized personnel, based on job function and role, in order to reduce the likelihood of malicious insiders compromising or leaking the data. In addition, robust authentication controls, such as multi-factor authentication and single sign-on, prohibit data flowing in and out like the tides.

For additional safety measures, consumer DNA testing companies conduct penetration testing and offer a bug bounty program to shore up vulnerabilities in their web application. Even more care has been taken with security training and awareness programs for employees, and incident management and response plans were developed with guidance from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

In the words of the great John Hammond: They spared no expense.

When Hunt made the call to Ancestry about the breach, he recalls that they responded quickly and professionally, unlike other organizations he’s contacted about data leaks and breaches.

“There’s always a range of ways organizations tend to deal with this. In some cases, they really don’t want to know. They put up the shutters and stick their head in the sand. In some cases, they deny it, even if the data is right there in front of them.”

Thankfully, that does not seem to be the case for the major DNA testing businesses.

Area of concern: law enforcement

At-home DNA testing kit companies are a little vague about when and under which conditions they would hand over your information to law enforcement, using terms such as “under certain circumstances” and “we have to comply with valid requests” without defining the circumstances or indicating what would be considered “valid.” However, they do provide this transparency report that details government requests for data and how they have responded.

Yet, news broke earlier this year that DNA from public database GEDmatch was used to find the Golden State Killer, and it gave consumers collective pause. While putting a serial killer behind bars is worthy cause, the killer was found because a relative of his had participated in a commercial DNA test and uploaded the results to GEDmatch. California investigators ran their old evidence through the open-source database, and found that the relative’s DNA was a close enough match to DNA found at the original 1970’s crime scenes. Through a series of deductions, they were able to rule out other relatives and pin down the real killer.

This opens up a can of worms about the impact of commercially-generated genetic data being available to law enforcement or other government bodies. How else could this data be used or even abused by police, investigators, or legislatures? The success of the Golden State Killer arrest could lead to re-opening other high-profile cold cases, or eventually turning to the consumer DNA databases every time there’s DNA evidence found at the scene of a crime.

Because so many individuals have now signed up for commercial DNA tests, odds are 60 percent and rising that, if you live in the US and are of European descent, you can be identified by information that your relatives have made public. In fact, law enforcement soon may not need a family member to have submitted DNA in order to find matches. According to a study published in Science, that figure will soon rise to 100 percent as consumer DNA databases reach critical mass.

What’s the big deal if DNA is used to capture criminals, though? Putting on my tinfoil hat for a second, I imagine a Minority-Report-esque scenario of stopping future crimes or misinterpreting DNA and imprisoning the wrong person. While those scenarios are a little far-fetched, I didn’t have to look too hard for real-life instances of abuse.

In July 2018, Vice reported that Canada’s border agency was using data from Ancestry.com and Familytreedna.com to establish nationalities of migrants and deport those it found suspect. In an era of high tensions on race, nationality, and immigration, it’s not hard to see how genetic data could be used against an individual or family for any number of civil or human rights violations.

Area of concern: accuracy of testing results

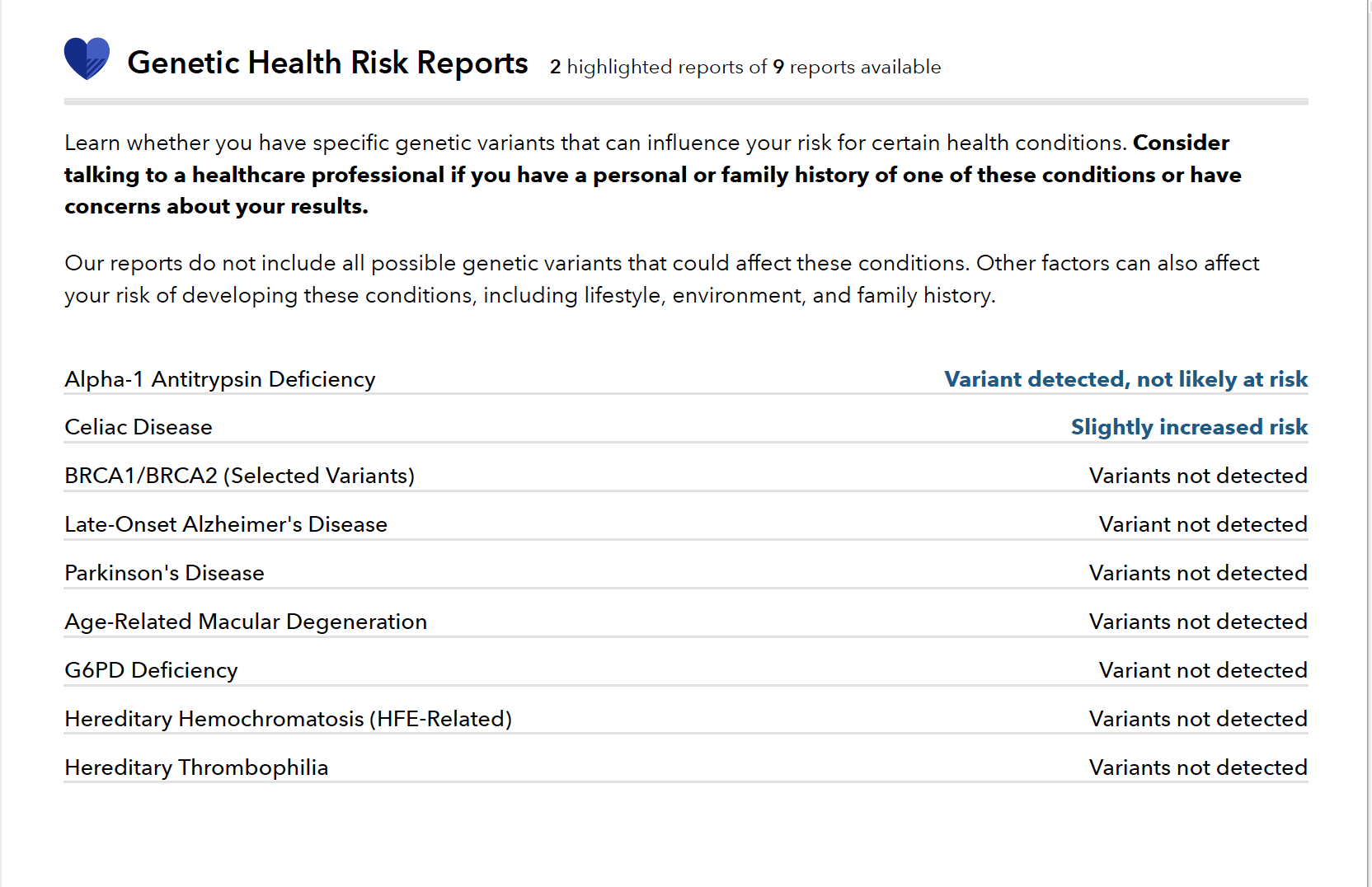

While this doesn’t technically fall under the guise of cybersecurity, the accuracy of test results is of concern because these companies are doling out incredibly sensitive information that has the potential to levy dramatic change on peoples’ lives. A March 2018 study in Nature found that 40 percent of results from at-home DNA testing kits were false positives, meaning someone was deemed “at risk” for a category that later turned out to be benign. That statistic is validated by the fact that test results from different consumer testing companies can vary dramatically.

The relative inaccuracy of the test results is compounded by the knowledge that there’s a lot of room to misinterpret them. Whether it’s learning you’re high risk for Alzheimer’s or discovering that your father is not really your father, health and ancestry data can be consumed without context, and with no doctor or genetic counselor on hand to soften the blow.

In fact, consumer DNA testing companies are rather reticent to send their users to genetic counselors—it’s essentially antithetical to their mission, which is to make genetic data more accessible to their customers.

Brianne Kirkpatrick, a genetic counselor and ancestry expert with the National Society for Genetic Counselors (NSGC), said that 23andMe once had a fairly prominent link on their website for finding genetic counselors to help users understand their results. That link is now either buried or gone. In addition, she mentioned that a one of her clients had to call 23andMe three times until they finally agreed to recommend Kirkpatrick’s counseling services.

“The biggest drawback is people believing that they understand the results when maybe they don’t,” she said. “For example, people don’t understand that the BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing these companies provide is really only helpful if you’re Ashkenazi Jew. In the fine print, it says they look at three variants out of thousands, and these three are only for this population. But people rush to make a conclusion because at a high level it looks like they should be either relieved or worried. It’s complex information, which is why genetic counselors exist in the first place.”

But what’s the symbology?

The data becomes even more messy when you move beyond users of European descent. People of color, especially those of Asian or African descent, have had a particularly hard go of it because they are underrepresented in many companies’ data sets. Often, black, Hispanic, or Asian users receive reports that list parts of their heritage as “low confidence” because their DNA doesn’t sufficiently match the company’s points of reference.

DNA testing companies not only offer sometimes incomplete, inaccurate information that’s easy to misunderstand to their customers, they also provide the raw data output that can be downloaded and then sent to third party websites, like GEDmatch, for even more evaluation. But those sites have not been as historically well-protected as the major consumer DNA testing companies. Once again, the security and privacy of genetic data goes fluttering away into the ether when users upload it, unencrypted and unprotected, to third-party platforms.

Doing it right: privacy policy

As an emerging industry, there’s little in the way of regulation or public policy when it comes to consumer genetic testing. Laboratory testing is bound by Medicare and Medicaid clauses, and commercial companies are regulated by the FDA, but DNA testing companies are a little of both, with the added complexity of operating online. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) launched in May 2018 requires companies to publicly disclose whether they’ve experienced a cyberattack, and imposes heavy fines for those who are not in compliance. But GDPR only applies to companies doing business in Europe.

As far as legal precedent is concerned, the 1990 California Supreme Court case Moore vs. Regents of the University of California found that individuals no longer have claim over their genetic data once they relinquish it for medical testing or other forms of study. So if Ancestry sells your DNA to a pharmaceutical company that then uses your cells to find the cure for cancer, you won’t see a dime of compensation. Bummer.

Despite the many opportunities for data to be stolen, abused, misunderstood, and sold to the highest bidder, the law simply hasn’t caught up to our technology. So the teams developing security and privacy policies for DNA testing companies are doing pioneering work, embracing security best practices and transparency at every turn. This is the right thing to do.

Almost two years ago, founders at Helix started working with privacy experts in order to understand all the key pieces they would need to safeguard—and they recognized that there was a need to form a formal coalition to enhance collaboration across the industry.

Through the Future of Privacy forum, they developed an independent think tank focused on creating public policy that leaders in the industry could follow. They teamed up with representatives from 23andMe, Ancestry, and others to create a set of standards that primarily hammered on the importance of transparency and clear communication with consumers.

“It is something that we are very passionate about,” said Misha Rashkin, Senior Genetic Counselor at Helix, and an active member of developing the shared privacy policy. “We’ve spent our careers explaining genetics to people, so there’s a years-long held belief that transparent, appropriate education—meaning developing policy at an approachable reading level—has got to be a cornerstone of people interacting with their DNA.”

While the privacy coalition strived for easy-to-understand language, the fact remains that their privacy policy is a 21-page document that most people are going to ignore. Rashkin and other team members were aware, so they built more touch points for customers to drill into the data and provide consent, including in-product notifications, emails, blog posts, and infographics delivered to customers as they continued to interact with their data on the platform.

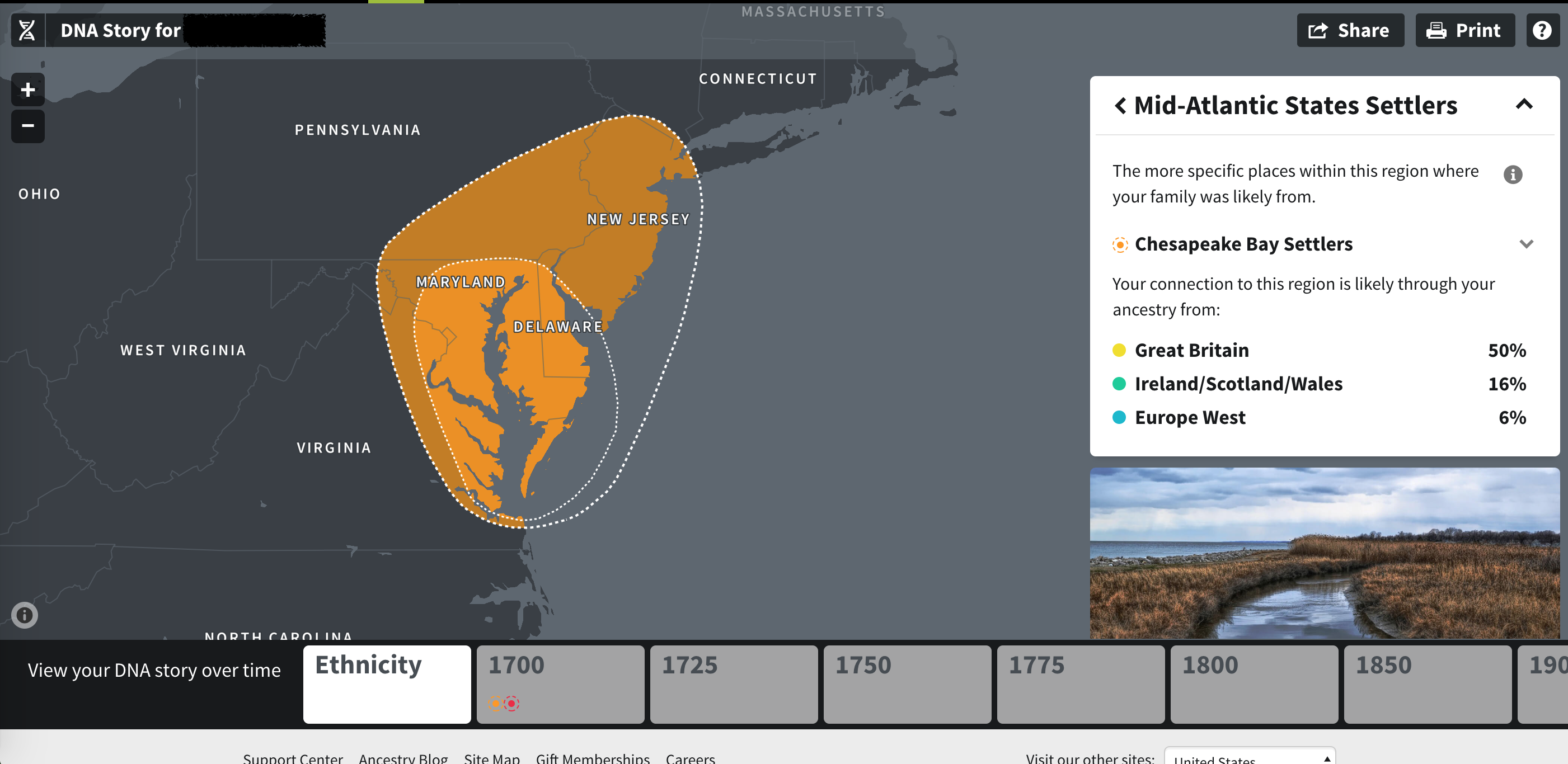

Maps, diagrams, charts, and other visuals help users better understand their data.

After Rashkin and company finalized and published their privacy policy, they turned it into a checklist that partners could use to determine baseline security and privacy standards, and what companies need to do to be compliant. But the work won’t stop there.

“This is just the beginning,” said Elissa Levin, Senior Director of Clinical Affairs and Policy at Helix, and a founding member of the privacy policy coalition. “As the industry evolves, we are planning on continuing to work on these standards and progress them. And then we’re actually going out to educate policy makers and regulators and the public in general. We want to help them determine what these policies are and differentiate who are the good players and who are the not-so-good players.”

Biggest area of concern: the unknown

We just don’t know what we don’t know when it comes to technology. When Mark Zuckerberg invented Facebook, he merely wanted an easy way to look at pretty college girls. I don’t think it entered his wildest dreams that his company’s platform could be used to directly interfere with a presidential election, or lead to the genocide of citizens in Myanmar. But because of a lack of foresight and an inability to move quickly to right the ship, we’re now all mired in the mud.

Right now, cybercriminals aren’t searching for DNA on the black market, but that doesn’t mean they won’t. Cybercrime often follows the path of least resistance—what takes the least amount of effort for the biggest payoff? That’s why social engineering attacks still vastly outnumber traditional malware infection vectors.

Because of that, cybercriminals likely believe it’s not worth jumping through hoops to try and break serious encryption for a product (genetic data) that’s not in demand—yet. But as biometrics and fingerprinting and other biological modes of authentication become more popular, I imagine it’s only a matter of time before the wagons start circling.

And yet—does it even matter? Even with all of the red flags exposed, millions of customers have taken the leap of faith because their curiosity overpowers their fear, or the immediate gratification is more satisfying than the nebulous, vague “what ifs” that we in the security community haven’t solved for. With so much data publicly available, do people even care about privacy anymore?

“There are changing sentiments about personal data among generations,” said Hunt. “There’s this entire generation who has grown up sharing their whole world online. This is their new social norm. We’re normalizing the collection of this information. I think if we were to say it’s a bad thing, we’d be projecting our more privacy-conscience viewpoints on them.”

Others believe that, regardless of personal feelings on privacy, this technology isn’t going away, so we—security experts, consumers, policy makers, and genetic testers alike—need to address its complex security and privacy issues head on.

“Privacy is such a personal matter. And while there may be trends, that doesn’t necessarily speak to an entire generation. There are people who are more open and there are people who are more concerned,” said Levin. “Whether someone is concerned or not, we are going to set these standards and abide by these practices because we think it’s important to protect people, even if they don’t think it’s critical. Fundamentally, it does come down to being transparent and helping people be aware of the risk to at least mitigate surprises.”

Indeed, whether privacy is personally important to you or not, understanding which data is being collected from where and how companies benefit from using your data makes you a more well-informed consumer.

Don’t just check that box. Look deeper, ask questions, and do some self-reflection about what’s important to you. Because right now, if someone steals your data, you might have to change a few passwords or cancel a couple credit cards. You might even be embroiled in identity theft hell. But we have no idea what the consequences will be if someone steals your genetic code.

Laws change and society changes. What’s legal and sanctioned now may not be in the future. But that data is going to be around a long time. And you cannot change your DNA.