Secure messaging is supposed to be just that—secure. That means no backdoors, strong encryption, private messages staying private, and, for some users, the ability to securely communicate without giving up tons of personal data.

So, when news broke that scandal-ridden, online privacy pariah Facebook would expand secure messaging across its Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram apps, a broad community of cryptographers, lawmakers, and users asked: Wait, what?

Not only is the technology difficult to implement, the company implementing it has a poor track record with both user privacy and online security.

On January 25, the New York Times reported that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg had begun plans to integrate the company’s three messaging platforms into one service, allowing users to potentially communicate with one another across its separate mobile apps. According to the New York Times, Zuckerberg “ordered that the apps all incorporate end-to-end encryption.”

The initial response was harsh.

Abroad, Ireland’s Data Protection Commission, which regulates Facebook in the European Union, immediately asked for an “urgent briefing” from the company, warning that previous data-sharing proposals raised “significant data protection concerns.”

In the United States, Democratic Senator Ed Markey for Massachusetts said in a statement: “We cannot allow platform integration to become privacy disintegration.”

Cybersecurity technologists swayed between cautious optimism and just plain caution.

Some professionals focused on the clear benefits of enabling end-to-end encryption across Facebook’s messaging platforms, emphasizing that any end-to-end encryption is better than none.

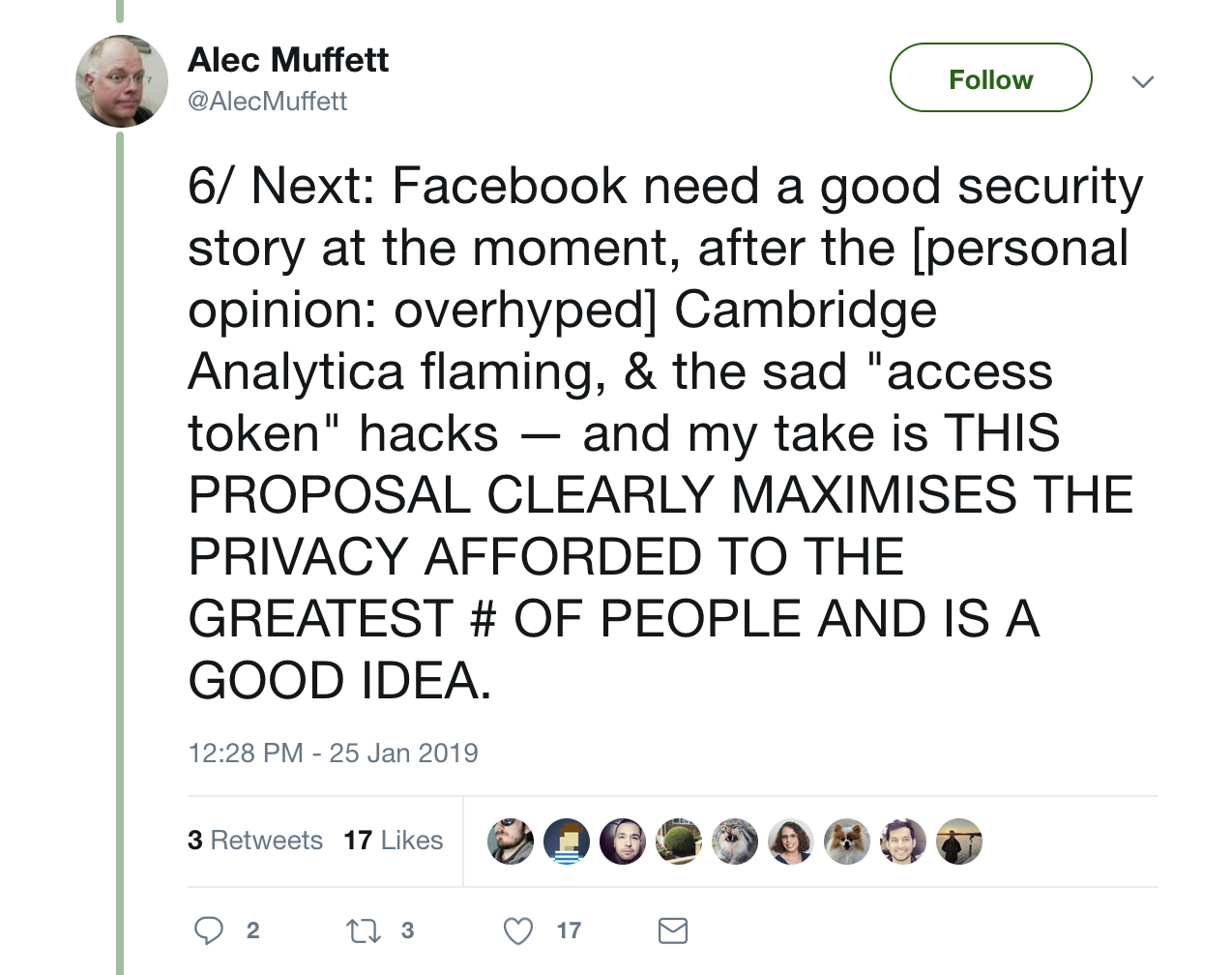

Former Facebook software engineer Alec Muffet, who led the team that added end-to-end encryption to Facebook Messenger, said on Twitter that the integration plan “clearly maximises the privacy afforded to the greatest [number] of people and is a good idea.”

Others questioned Facebook’s motives and reputation, scrutinizing the company’s established business model of hoovering up mass quantities of user data to deliver targeted ads.

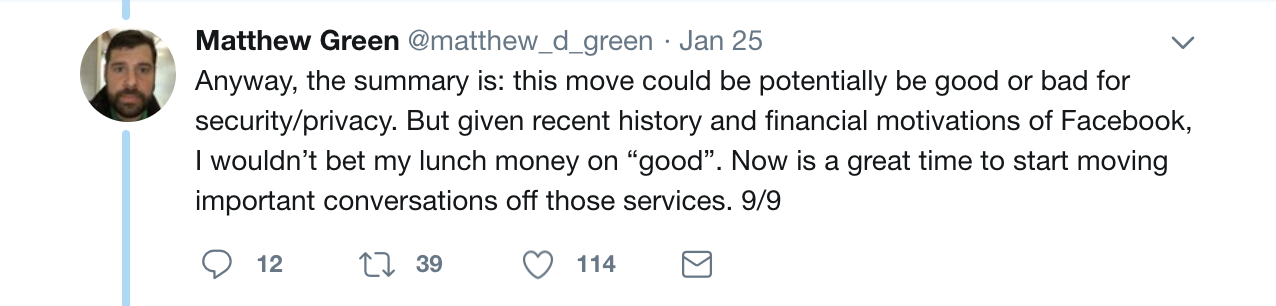

John Hopkins University Associate Professor and cryptographer Matthew Green said on Twitter that “this move could potentially be good or bad for security/privacy. But given recent history and financial motivations of Facebook, I wouldn’t bet my lunch money on ‘good.’”

On January 30, Zuckerberg confirmed the integration plan during a quarterly earnings call. The company hopes to complete the project either this year or in early 2020.

It’s going to be an uphill battle.

Three applications, one bad reputation

Merging three separate messaging apps is easier said than done.

In a phone interview, Green said Facebook’s immediate technological hurdle will be integrating “three different systems—one that doesn’t have any end-to-end encryption, one where it’s default, and one with an optional feature.”

Currently, the messaging services across WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Instagram have varying degrees of end-to-end encryption. WhatsApp provides default end-to-end encryption, whereas Facebook Messenger provides optional end-to-end encryption if users turn on “Secret Conversations.” Instagram provides no end-to-end encryption in its messaging service.

Further, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram all have separate features—like Facebook Messenger’s ability to support more than one device and WhatsApp’s support for group conversations—along with separate desktop or web clients.

Green said to imagine someone using Facebook Messenger’s web client—which doesn’t currently support end-to-end encryption—starting a conversation with a WhatsApp user, where encryption is set by default. These lapses in default encryption, Green said, could create vulnerabilities. The challenge is in pulling together all those systems with all those variables.

“First, Facebook will have to likely make one platform, then move all those different systems into one somewhat compatible system, which, as far as I can tell, would include centralizing key servers, using the same protocol, and a bunch of technical development that has to happen,” Green said. “It’s not impossible. Just hard.”

But there’s more to Facebook’s success than the technical know-how of its engineers. There’s also its reputation, which, as of late, portrays the company as a modern-day data baron, faceplanting into privacy failure after privacy failure.

After the 2016 US presidential election, Facebook refused to call the surreptitious collection of 50 million users’ personal information a “breach.” When brought before Congress to testify about his company’s role in a potential international disinformation campaign, Zuckerberg deflected difficult questions and repeatedly claimed the company does not “sell” user data to advertisers. But less than one year later, a British parliamentary committee released documents that showed how Facebook gave some companies, including Airbnb and Netflix, access to its platform in exchange for favors—no selling required.

Five months ago, Facebook’s Onavo app was booted from the Apple App Store for gathering app data, and early this year, Facebook reportedly paid users as young as 13-years-old to install the “Facebook Research” app on their own devices, an app intended strictly for Facebook employee use. Facebook pulled the app, but Apple had extra repercussions in mind: It removed Facebook’s enterprise certificate, which the company relied on to run its internal developer apps.

These repeated privacy failures are enough for some users to avoid Facebook’s end-to-end encryption experiment entirely.

“If you don’t trust Facebook, the place to worry is not about them screwing up the encryption,” Green said. “They want to know who’s talking to who and when. Encryption doesn’t protect that at all.”

If not Facebook, then who?

Reputationally, there are at least two companies that users look to for both strong end-to-end encryption and strong support of user privacy and security—Apple and Signal, which respectively run the iMessage and Signal Messenger apps.

In 2013, Open Whisper Systems developed the Signal Protocol. This encryption protocol provides end-to-end encryption for voice calls, video calls, and instant messaging, and is implemented by WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Google’s Allo, and Microsoft’s Skype to varying degrees. Journalists, privacy advocates, cryptographers, and cybersecurity researchers routinely praise Signal Messenger, the Signal Protocol, and Open Whisper Systems.

“Use anything by Open Whisper Systems,” said former NSA defense contractor and government whistleblower Edward Snowden.

“[Signal is] my first choice for an encrypted conversation,” said cybersecurity researcher and digital privacy advocate Bruce Schneier.

Separately, Apple has proved its commitment to user privacy and security through statements made by company executives, updates pushed to fix vulnerabilities, and legal action taken in US courts.

In 2016, Apple fought back against a government request that the company design an operating system capable of allowing the FBI to crack an individual iPhone. Such an exploit, Apple argued, would be too dangerous to create. Earlier last year, when an American startup began selling iPhone-cracking devices—called GrayKey—Apple fixed the vulnerability through an iOS update.

Repeatedly, Apple CEO Tim Cook has supported user security and privacy, saying in 2015: “We believe that people have a fundamental right to privacy. The American people demand it, the constitution demands it, morality demands it.”

But even with these sterling reputations, the truth is, cybersecurity is hard to get right.

Last year, cybersecurity researchers found a critical vulnerability in Signal’s desktop app that allowed threat actors to obtain users’ plaintext messages. Signal’s developers fixed the vulnerability within a reported five hours.

Last week, Apple’s FaceTime app, which encrypts video calls between users, suffered a privacy bug that allowed threat actors to briefly spy on victims. Apple fixed the bug after news of the vulnerability spread.

In fact, several secure messaging apps, including Telegram, Viber, Confide, Allo, and WhatsApp have all reportedly experienced security vulnerabilities, while several others, including Wire, have previously drawn ire because of data storage practices.

But vulnerabilities should not scare people from using end-to-end encryption altogether. On the contrary, they should spur people into finding the right end-to-end encrypted messaging app for themselves.

No one-size-fits-all, and that’s okay

There is no such thing as a perfect, one-size-fits-all secure messaging app, said Electronic Frontier Foundation Associate Director of Research Gennie Gebhart, because there’s no such thing as a perfect, one-size-fits-all definition of secure.

“In practice, for some people, secure means the government cannot intercept their messages,” Gebhart said. “For others, secure means a partner in their physical space can’t grab their device and read their messages. Those are two completely different tasks for one app to accomplish.”

In choosing the right secure messaging app for themselves, Gebhart said people should ask what they need and what they want. Are they worried about governments or service providers intercepting their messages? Are they worried about people in their physical environment gaining access to their messages? Are they worried about giving up their phone number and losing some anonymity?

In addition, it’s worth asking: What are the risks of an accident, like, say, mistakenly sending an unencrypted message that should have been encrypted? And, of course, what app are friends and family using?

As for the constant news of vulnerabilities in secure messaging apps, Gebhart advised not to overreact. The good news is, if you’re reading about a vulnerability in a secure messaging tool, then the people building that tool know about the vulnerability, too. (Indeed, developers fixed the majority of the security vulnerabilities listed above.) The best advice in that situation, Gebhart said, is to update your software.

“That’s number one,” Gebhart said, explaining that, though this line of defense is “tedious and maybe boring,” sometimes boring advice just works. “Brush your teeth, lock your door, update your software.”

Cybersecurity is many things. It’s difficult, it’s complex, and it’s a team sport. That team includes you, the user. Before you use a messenger service, or go online at all, remember to follow the boring advice. You’ll better secure yourself and your privacy.