By William Tsing, Vasilios Hioureas, and Jérôme Segura

Over the past few months, we have noticed increased activity and development of new stealers. Unlike many banking Trojans that wait for the victim to log into their bank’s website, stealers typically operate in grab-and-go mode. This means that upon infection, the malware will collect all the data it needs and exfiltrate it right away. Because such stealers are often non-resident (meaning they have no persistence mechanism) unless they are detected at the time of the attack, victims will be none-the-wiser that they have been compromised.

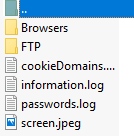

This type of malware is popular among criminals and covers a greater surface than more specialized bankers. On top of capturing browser history, stored passwords, and cookies, stealers will also look for files that may contain valuable data.

In this blog post, we will review the Baldr stealer which first appeared in underground forums in January 2019, and was later seen in the wild by Microsoft in February.

Baldr on the market

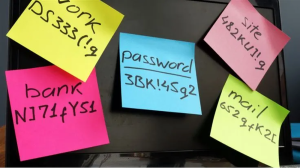

Baldr is likely the work of three threat actors: Agressor for distribution, Overdot for sales and promotion, and LordOdin for development. Appearing first in January, Baldr quickly generated many positive reviews on most of the popular clearnet Russian hacking forums.

Previously associated with the Arkei stealer (seen below), Overdot posts a majority of advertisements across multiple message boards, provides customer service via Jabber, and addresses buyer complaints in the reputational system used by several boards.

Of interest is a forums post referencing Overdot’s previous work with Arkei, where he claims that the developers of both Baldr and Arkei are in contact and collaborate on occasion.

Unlike most products posted on clearnet boards, Baldr has a reputation for reliability, and it also offers relatively good communication with the team behind it.

LordOdin, also known as BaldrOdin, has a significantly lower profile in conjunction with Baldr, but will monitor and like posts surrounding it.

He primarily posts to differentiate Baldr from competitor products like Azorult, and vouches that Baldr is not simply a reskin of Arkei:

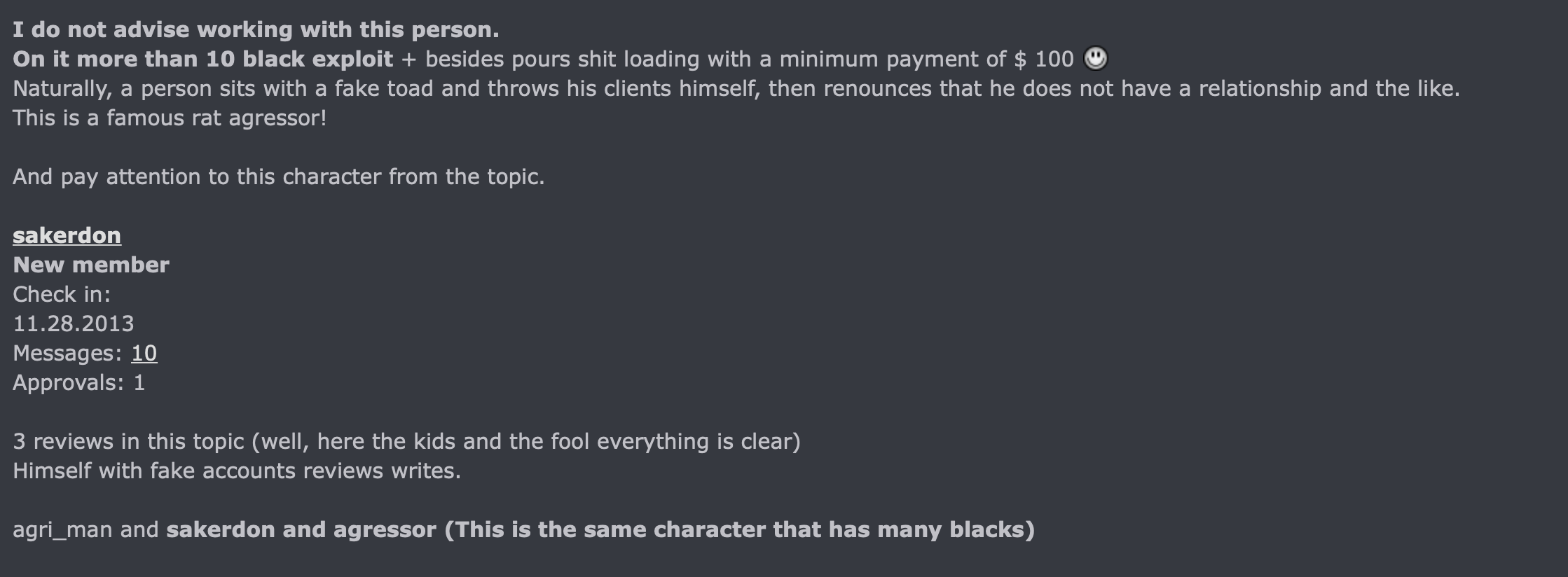

Agressor/Agri_MAN is the final player appearing in Baldr’s distribution:

Agri_MAN has a history of selling traffic on Russian hacking forums dating back roughly to 2011. In contrast to LordOdin and Overdot, he has a more checkered reputation, showing up on a blacklist for chargebacks, as well as getting called out for using sock puppet accounts to generate good reviews.

Using the alternate account Agressor, he currently maintains an automated shop to generate Baldr builds at service-shop[.]ml. Interestingly, Overdot makes reference to an automated installation bot that is not connected to them, and is generating complaints from customers:

This may indicate Agressor is an affiliate and not directly associated with Baldr development. At presstime, Overdot and LordOdin appear to be the primary threat actors managing Baldr.

Distribution

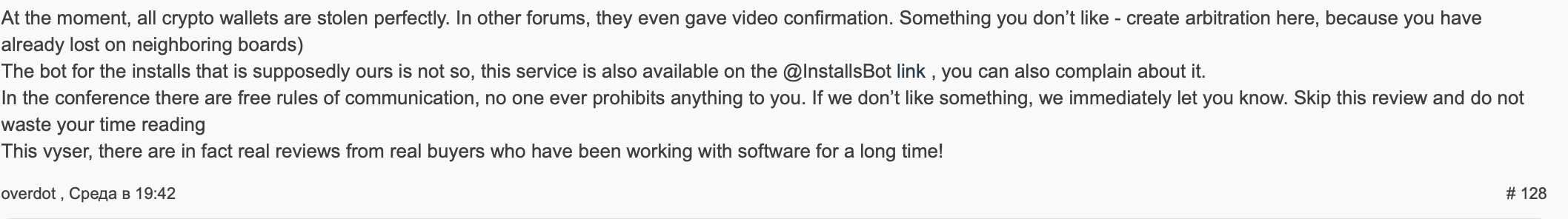

In our analysis of Baldr, we collected a few different versions, indicating that the malware has short development cycles. The latest version analyzed for this post is version 2.2, announced March 20:

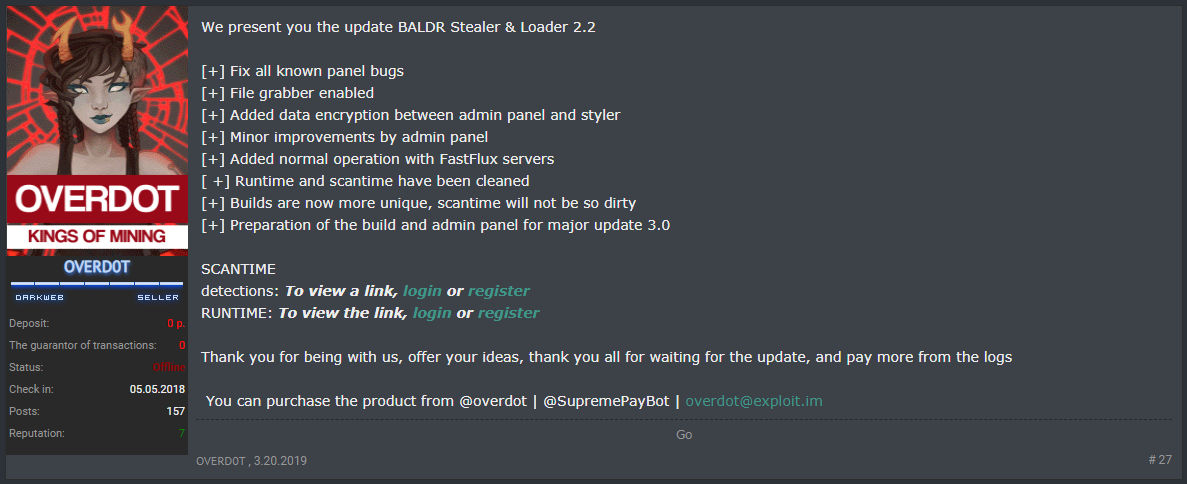

We captured Baldr via different distribution chains. One of the primary vectors is the use of Trojanized applications disguised as cracks or hack tools. For example, we saw a video posted to YouTube offering a program to generate free Bitcoins, but it was in fact the Baldr stealer in disguise.

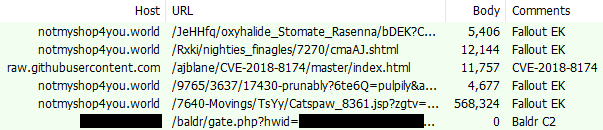

We also caught Baldr via a drive-by campaign involving the Fallout exploit kit:

Technical analysis (Baldr 2.2)

Baldr’s high level functionality is relatively straight forward, providing a small set of malicious abilities in the version of this analysis. There is nothing ground breaking as far as what it’s trying to do on the user’s computer, however, where this threat differentiates itself is in its extremely complicated implementation of that logic.

Typically, it is quite apparent when a malware is thrown together for a quick buck vs. when it is skillfully crafted for a long-running campaign. Baldr sits firmly in the latter category—it is not the work of a script kiddie. Whether we are talking about its packer usage, payload code structure, or even its backend C2 and distribution, it’s clear Baldr’s authors spent a lot of time developing this particular threat.

Functionality overview

Baldr’s main functionality can be broken down into five steps, which are completed in chronological order.

Step 1: User profiling

Baldr starts off by gathering a list of user profiling data. Everything from the user account name to disk space and OS type is enumerated for exfiltration.

Step 2: Sensitive data exfiltration

Next, Baldr begins cycling through all files and folders within key locations of the victim computer. Specifically, it looks in the user AppData and temp folders for information related to sensitive data. Below is a list of key locations and application data it searches:

AppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefault AppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultLogin Data AppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultCookies AppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultWeb Data AppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultHistory AppDataRoamingExodusexodus.wallet AppDataRoamingEthereumkeystore AppDataLocalProtonVPN WalletsJaxx Liberty NordVPN Telegram Jabber TotalCommander Ghisler

Many of these data files range from simple sqlite databases to other types of custom formats. The authors have a detailed knowledge of these target formats, as only the key data from these files is extracted and loaded into a series of arrays. After all the targeted data has been parsed and prepared, the malware continues onto its next functionality set.

Step 3: ShotGun file grabbing

DOC, DOCX, LOG, and TXT files are the targets in this stage. Baldr begins in the Documents and Desktop directories and recursively iterates all subdirectories. When it comes across a file with any of the above extensions, it simply grabs the entire file’s contents.

Step 4: ScreenCap

In this last data-gathering step, Baldr gives the controller the option of grabbing a screenshot of the user’s computer.

Step 5: Network exfiltration

After all of this data has been loaded into organized and categorized arrays/lists, Baldr flattens the arrays and prepares them for sending through the network.

One interesting note is that there is no attempt to make the data transfer more inconspicuous. In our analysis machine, we purposely provided an extreme number of files for Baldr to grab, wondering if the malware would slowly exfiltrate this large amount of data, or if it would just blast it back to the C2.

The result was one large and obvious network transfer. The malware does not have built-in functionality to remain resident on the victim’s machine. It has already harvested the data it desires and does not care to re-infect the same machine. In addition, there is no spreading mechanism in the code, so in a corporate environment, each employee would need to be manually targeted with a unique attempt.

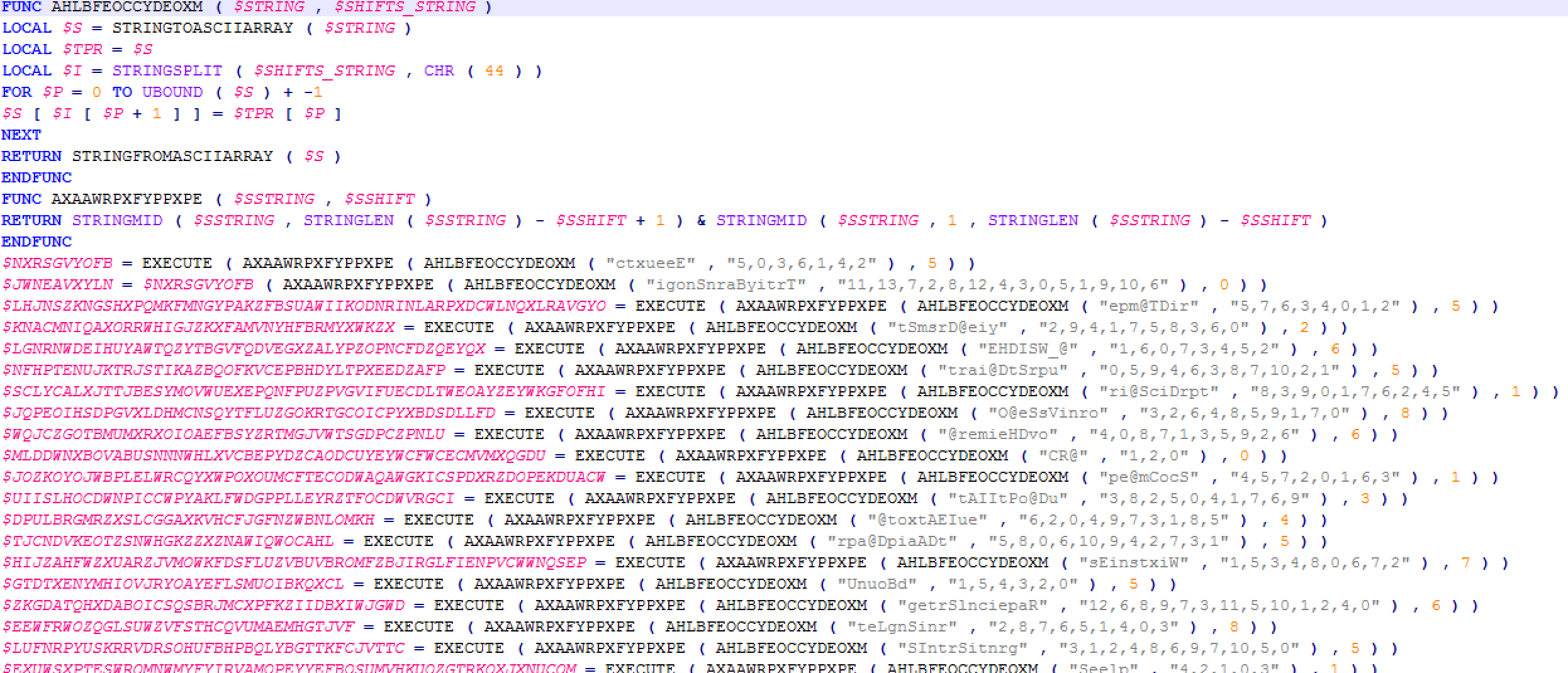

Packer code level analysis

We will begin with the payload obfuscation and packer usage. This version of Baldr starts off as an AutoIt script built into an exe. Using a freely available AIT decompiler, we got to the first stage of the packer below.

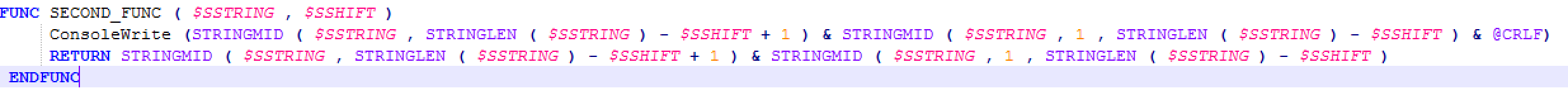

As you can see, this code is heavily obfuscated. The first two functions are the main workhorse of that obfuscation. What is going on here is simply reordering of the provided string, according to the indexes passed in as the second parameter. This, however, does not pose much of a problem as we can easily extract the strings generated by simply modifying this script to ConsoleWrite out the deobfuscated strings before returning:

The resulting strings extracted are below:

Execute BinaryToString @TempDir @SystemDir @SW_HIDE @StartupDir @ScriptDir @OSVersion @HomeDrive @CR @ComSpec @AutoItPID @AutoItExe @AppDataDir WinExists UBound StringReplace StringLen StringInStr Sleep ShellExecute RegWrite Random ProcessExists ProcessClose IsAdmin FileWrite FileSetAttrib FileRead FileOpen FileExists FileDelete FileClose DriveGetDrive DllStructSetData DllStructGet DllStructGetData DllStructCreate DllCallAddress DllCall DirCreate BinaryLen TrayIconHide :Zone.Identifier kernel32.dll handle CreateMutexW struct* FindResourceW kernel32.dll dword SizeofResource kernel32.dll LoadResource kernel32.dll LockResource byte[ VirtualAlloc byte shellcode [

In addition to these obvious function calls, we also have a number of binary blobs which get deobfuscated. We have included only a limited set of these strings as to not overload this analysis with long sets of data.

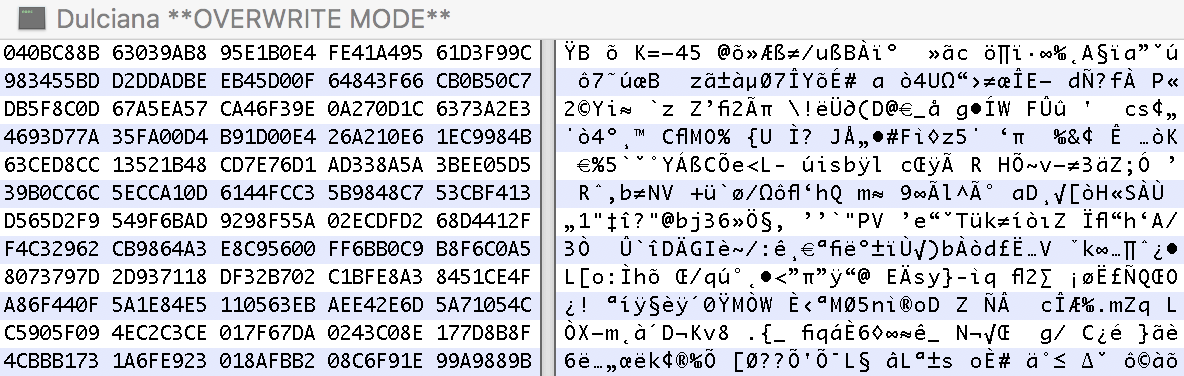

We can see that it is pulling and decrypting a resource DLL from within the main executable, which will be loaded into memory. This makes sense after analyzing a previous version of Baldr that did not use AIT as its first stage. The prior versions of Baldr required a secondary file named Dulciana. So, instead of using AIT, the previous versions used this file containing the encrypted bytes of the same DLL we see here:

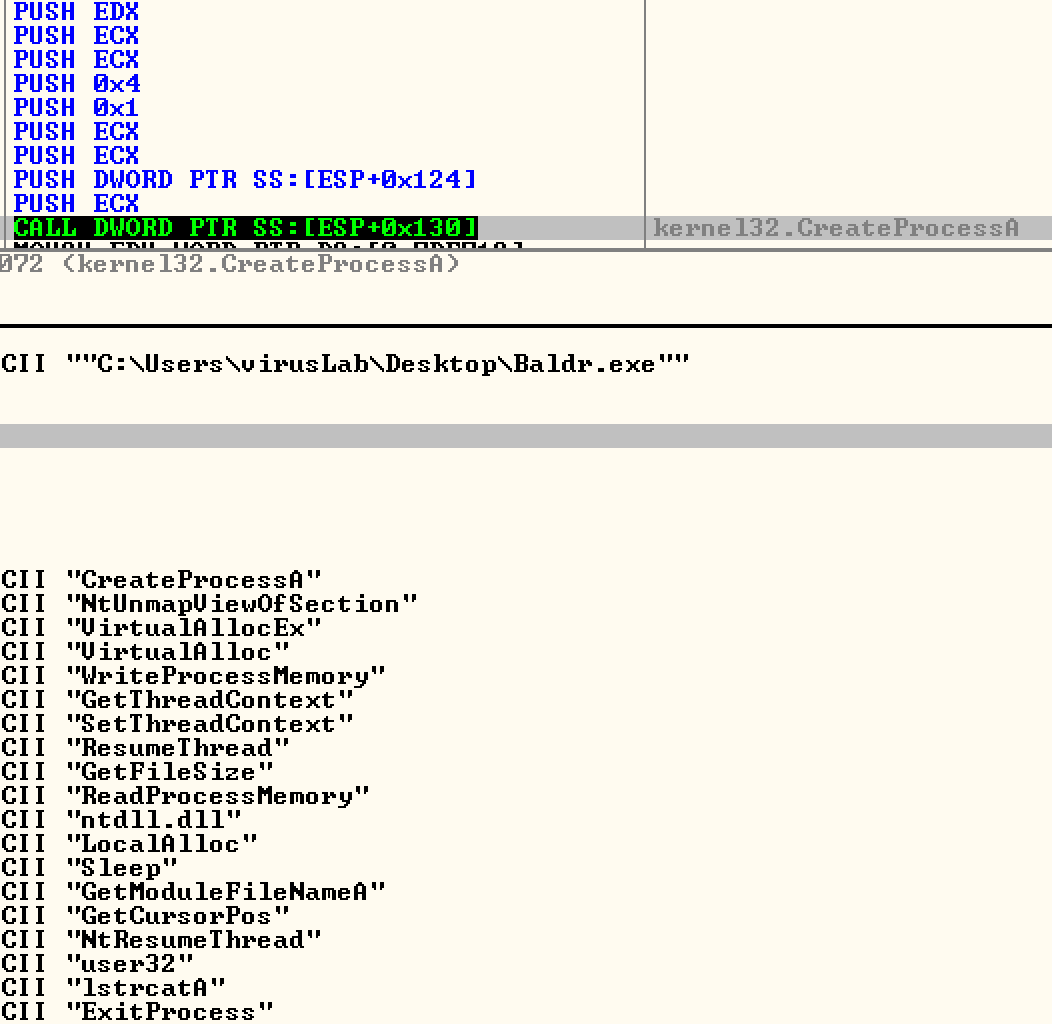

Moving forward to stage two, all things essentially remain equal throughout all versions of the Baldr packer. We have the DLL loaded into memory, which creates a child process of the main Baldr executable in a suspended state and proceeds to hollow this process, eventually replacing it with the main .NET payload. This makes manually unpacking with ollyDbg nice because after we break on child Baldr.exe load, we can step through the remaining code of the parent, which writes to process memory and eventually calls ResumeThread().

As you can see, once the child process is loaded, the functions that it has set up to call contain VirtualAlloc, WriteProcessMemory, and ResumeThread, which gives us an idea what to look out for. If we dump this written memory right before resume thread is called, we can then easily extract the main payload.

Our colleague @hasherezade has made this step-by-step video of unpacking Baldr:

Payload code analysis

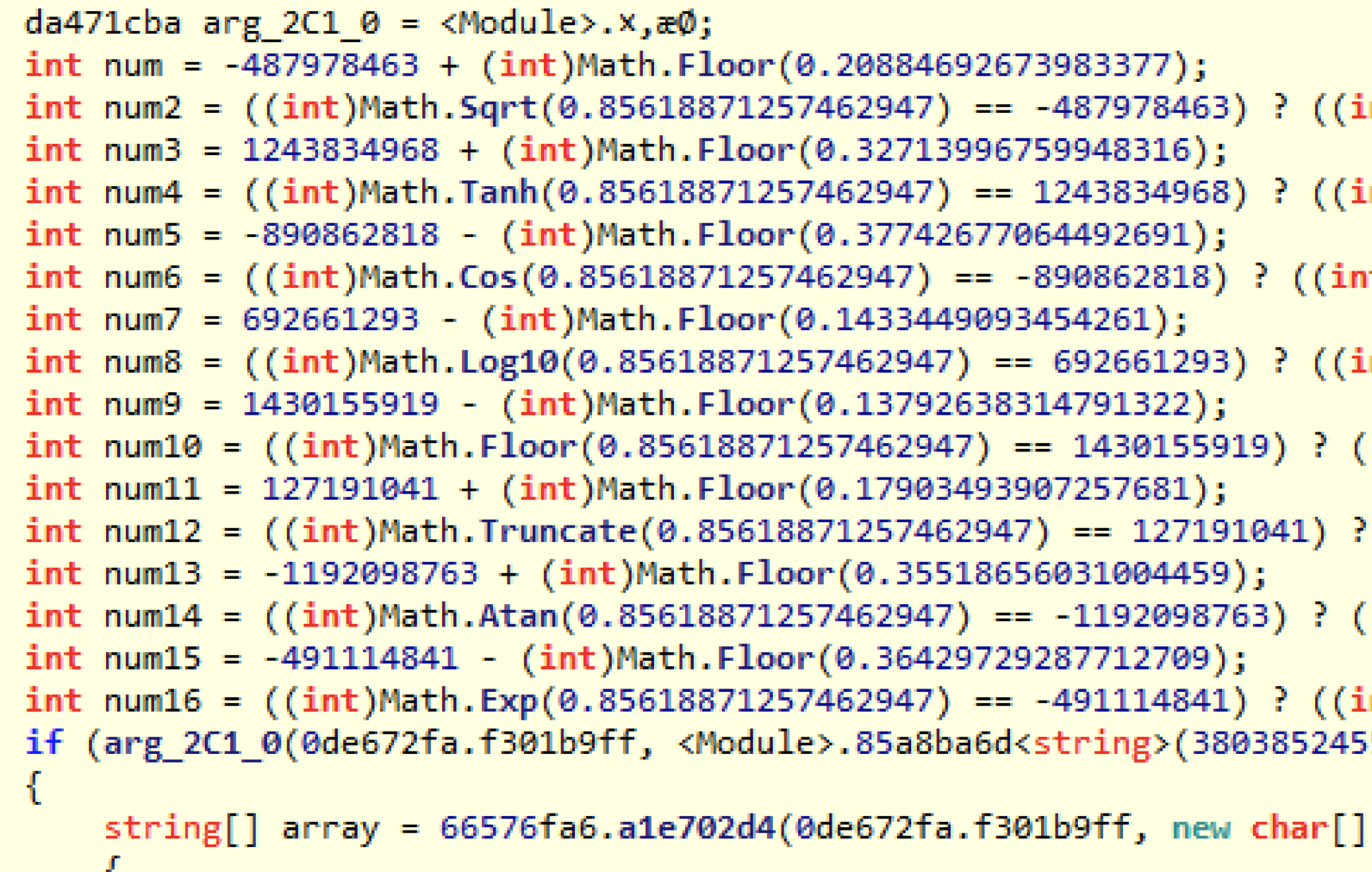

Now that we have unpacked the payload, we can see the actual malicious functionality. However, this is where our troubles began. For the most part, malware written in any interpreted language is a relief for a reverse engineer as far as ease of analysis goes. Baldr, on the other hand, managed to make the debugging and analysis of its source code a difficult task, despite being written in C#.

The code base of this malware is not straight forward. All functionality is heavily abstracted, encapsulated in wrapper functions, and utilizes a ton of utility classes. Going through this code base of around 80 separate classes and modules, it is not easy to see where the key functionality lies. Multiple static passes over the code base are necessary to begin making sense of it all. Add in the fact that the function names have been mangled and junk instructions are inserted throughout the code, and the next step would be to start debugging the exe with DnSpy.

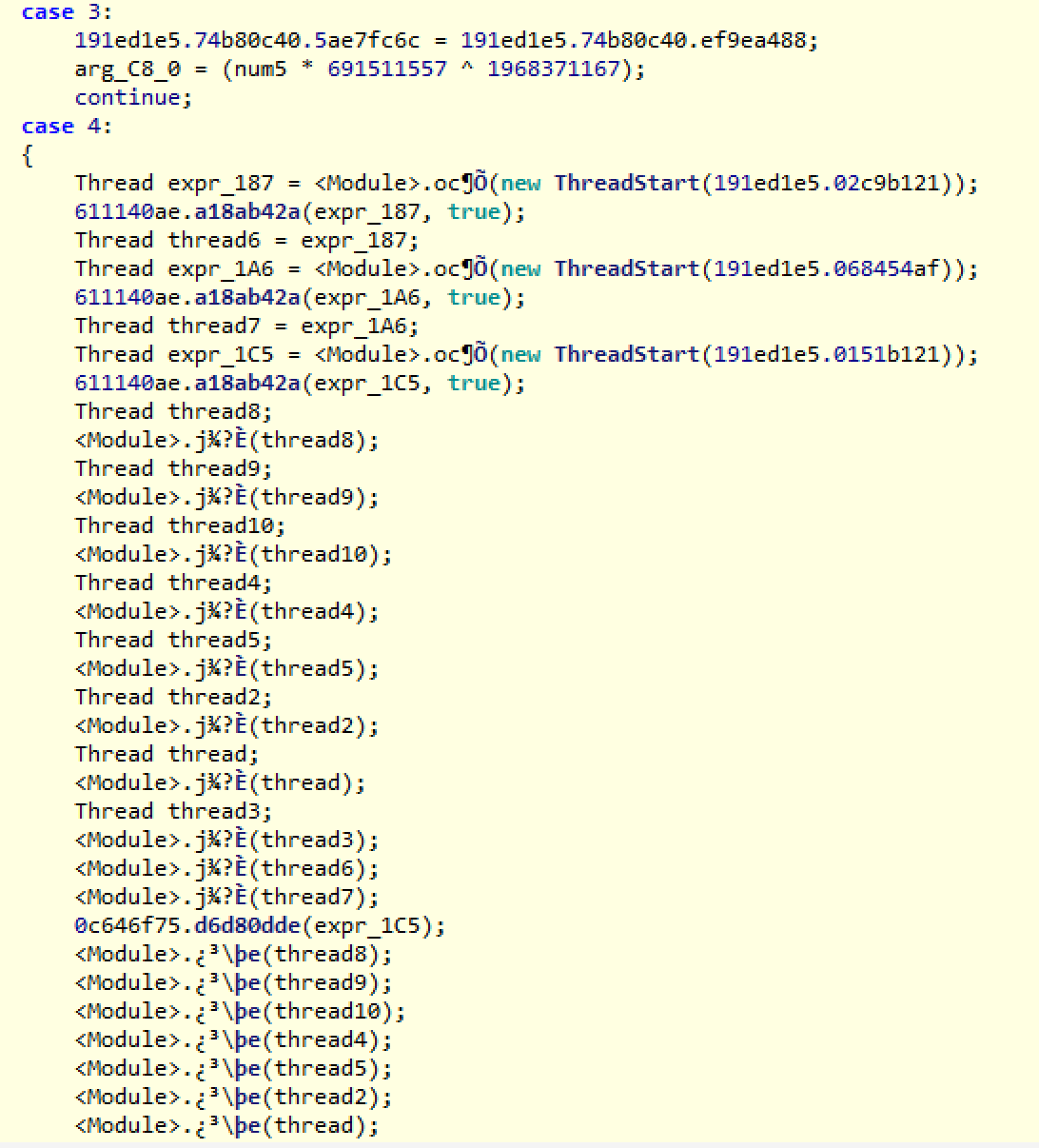

Now we get to our next problem: threads. Every minute action that this malware performs is executed through a separate thread. This was obviously done to complicate the life of the analyst. It would be accurate to say that there are over 100 unique functions being called inside of threads throughout the code base. This does not include the threads being called recursively, which could become thousands.

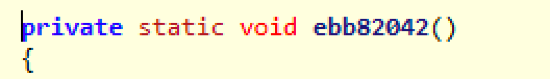

Luckily, we can view local data as it is being written, and eventually we are able to locate the key sections of code:

“>

The function pictured above gathers the user’s profile, as mentioned previously. This includes the CPU type, computer name, user accounts, and OS.

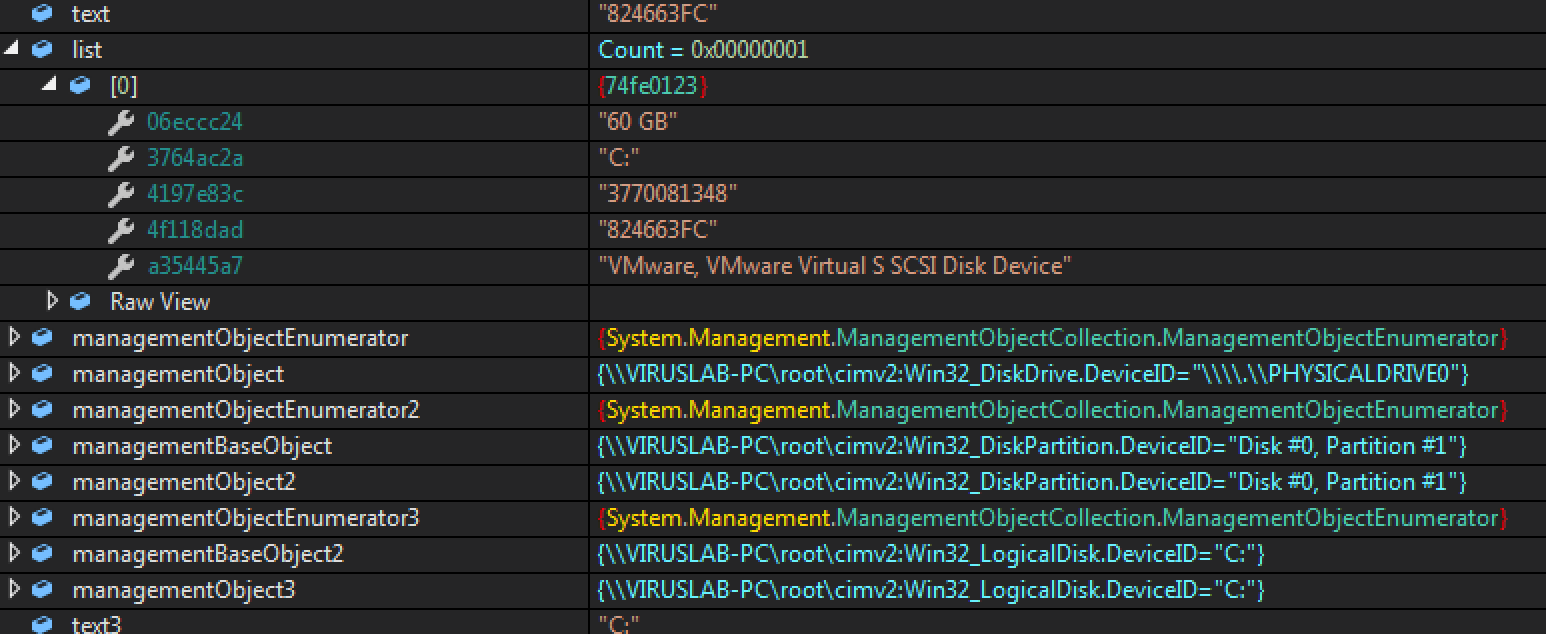

After the entire process is complete, it flattens the arrays storing this data, resulting in a string like this:

The next section of code shows one of the many enumerator classes used to cycle directories, looking for application data, such as stored user accounts, which we purposely saved for testing.

“>

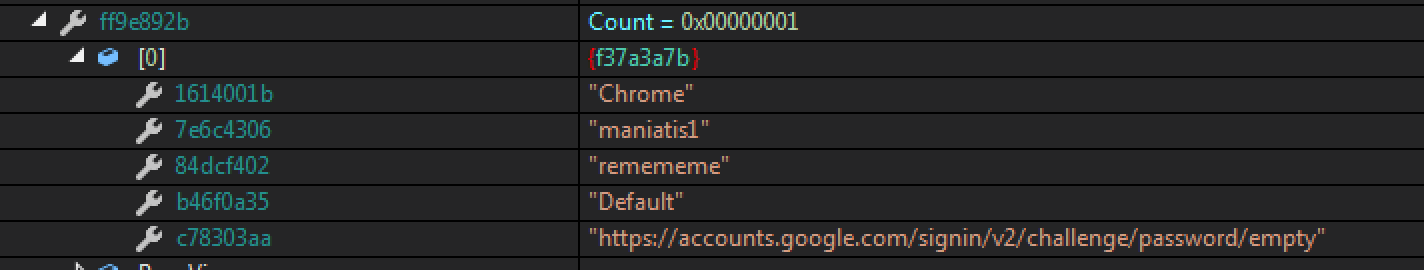

The data retrieved was saved into lists in the format below:

“>

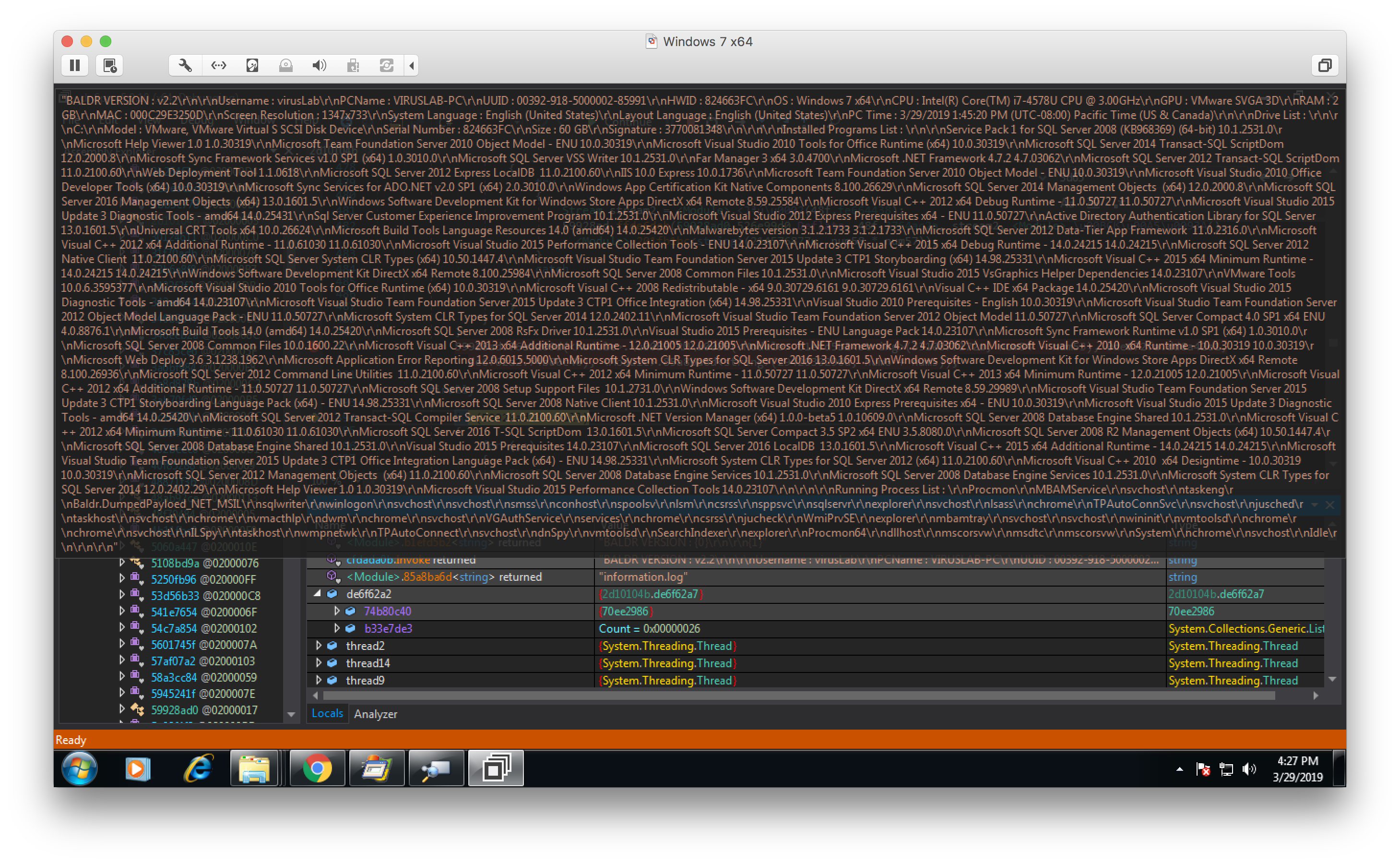

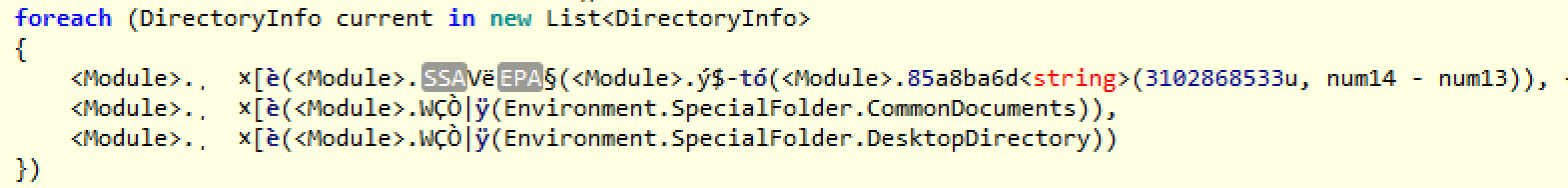

In the final stage of data collection, we have the threads below, which cycle the key directories looking for txt and doc files. It will save the filename of each txt or doc it finds, and store the file’s contents in various arrays.

“>

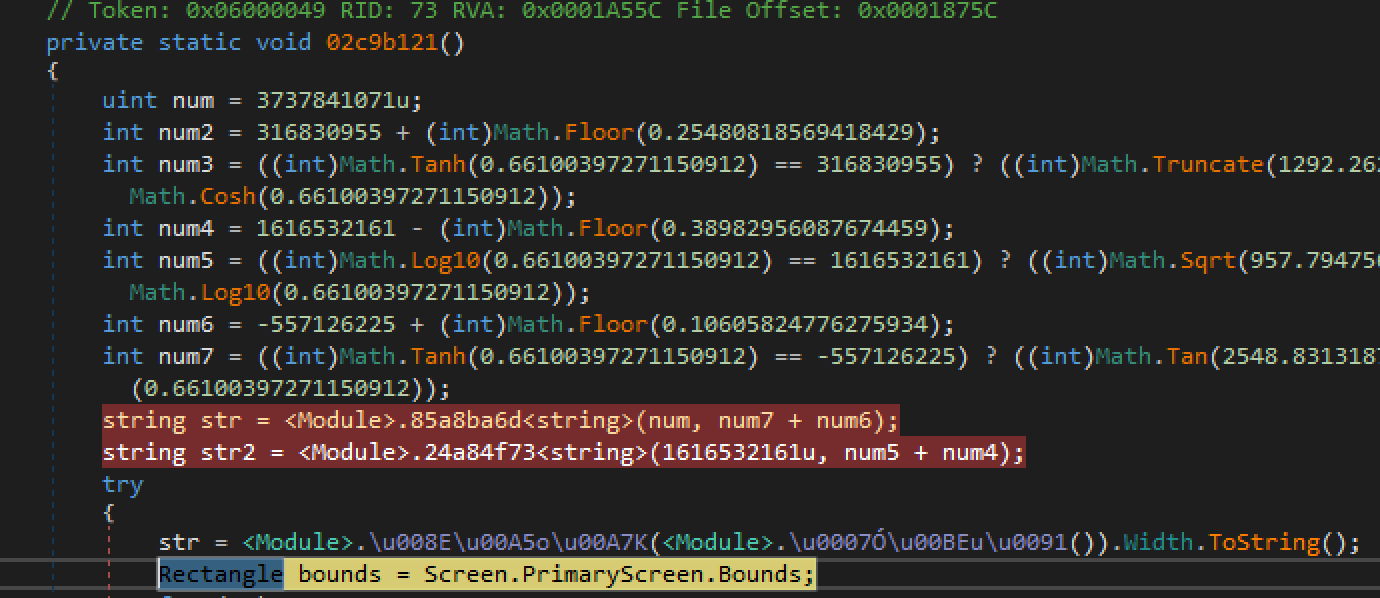

Finally, before we proceed to the network segment of the malware, we have the code section performing the screen captures:

Class 2d10104b function 1b0b685() is one of the main modules that branches out to do the majority of the functionality, such as looping through directories. Once all data has been gathered, the threads converge and the remaining lines of code continue single threaded. It is then that the network calls begin and all the data is sent back to the C2.

The zipped data is encrypted via XOR with a 4 byte key and version number obtained from contacting the C2 via a first network request. The second request sends the cyphered data back to the C2.

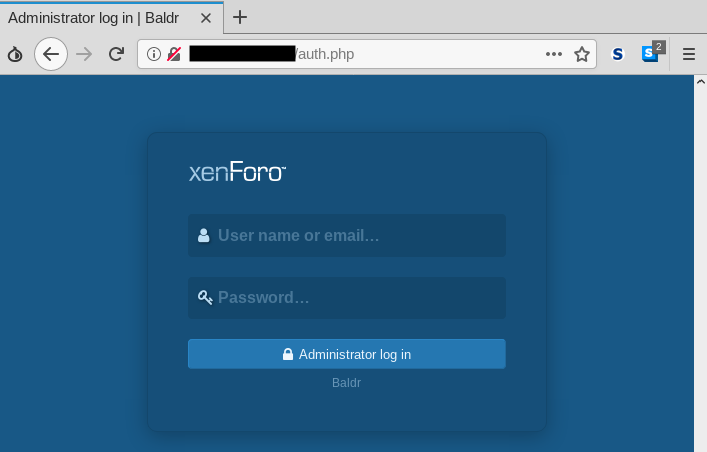

Panel

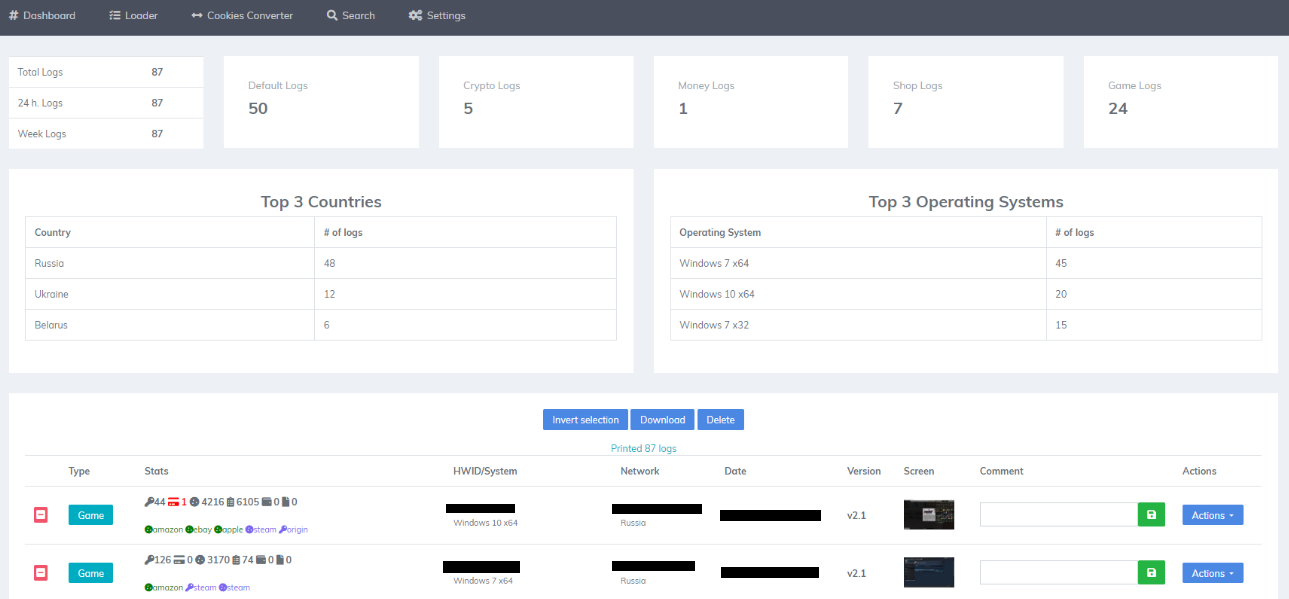

Like other stealers, Baldr comes with a panel that allows the customers (criminals that buy the product) to see high-level stats, as well as retrieve the stolen information. Below is a panel login page:

And here, in a screenshot posted by the threat actor on a forum, we see the inside of the panel:

Final analysis

Baldr is a solid stealer that is being distributed in the wild. Its author and distributor are active in various forums to promote and defend their product against critics. During a short time span of only a few months, Baldr has gone through many versions, suggesting that its author is fixing bugs and interested in developing new features.

Baldr will have to compete against other stealers and differentiate itself. However, the demand for such products is high, so we can expect to see many distributors use it as part of several campaigns.

Malwarebytes users are protected against this threat, detected as Spyware.Baldr.

Thanks to S!Ri for additional contributions.

Indicators of compromise

Baldr samples

5464be2fd1862f850bdb9fc5536eceafb60c49835dd112e0cd91dabef0ffcec5 -> version 1.2 1cd5f152cde33906c0be3b02a88b1d5133af3c7791bcde8f33eefed3199083a6 -> version 2.0 7b88d4ce3610e264648741c76101cb80fe1e5e0377ea0ee62d8eb3d0c2decb92 > version 2.2 8756ad881ad157b34bce011cc5d281f85d5195da1ed3443fa0a802b57de9962f (2.2 unpacked)

Network traces