Apple’s reputation on security has been taking a beating lately. As mentioned in some of our previous coverage, security researcher Joshua Long recently shone a light on problems with Apple’s security patching strategy. His findings showed a shocking number of cases where Apple patched a vulnerability, but did not do so in all of the vulnerable system versions. Often, systems older than the most current one were left in vulnerable states.

In theory, this could lead to attacks on those vulnerable systems. And new Mac malware that was disclosed on Thursday provides a concrete example of why this is not just theory.

Watering hole campaign discovered by Google

Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) discovered a watering hole campaign in Hong Kong, targeting journalists and pro-democracy political groups. This campaign was using two macOS vulnerabilities to infect Macs that simply visited the wrong web page.

A watering hole attack is one that’s deployed through a website that the desired target is likely to visit, so named because of the way predators will hide near a watering hole that is frequented by their prey.

The vulnerabilities were used to drop malware onto the computer silently, without the user needing to click on anything or even being aware that anything has happened. The malware itself is a pretty full-featured backdoor, but what is most remarkable about it is not its capabilities. This malware has been in the wild, with very few changes, since at least 2019. Back then, it was distributed as a trojan, in an installer disguised as – you’ll never guess – an Adobe Flash Player installer!

Some of the executable files dropped by this installer from 2019 are nearly the same as the ones currently in distribution, but were (as of Thursday) still undetected by any antivirus software.

The vulnerabilities had been fixed… sort of

The first vulnerability used by the malware was CVE-2021-1789, which was a remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability in WebKit. This means that it allowed an attacker to trick WebKit – the foundation of Safari and a number of other browsers – into executing arbitrary code, which is not supposed to be possible.

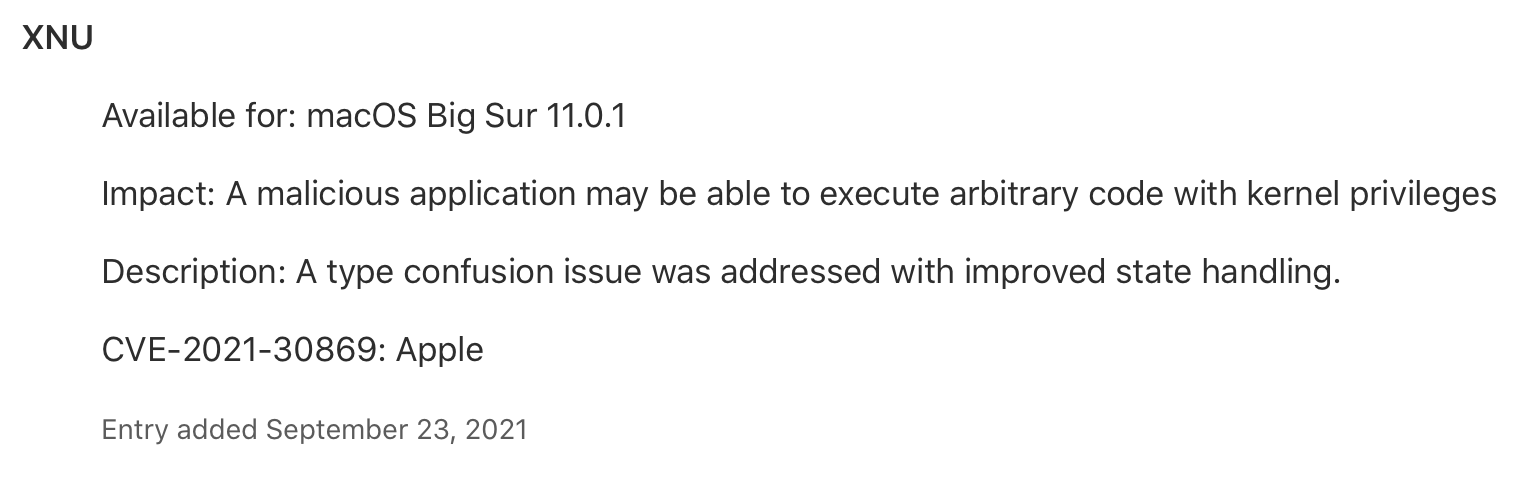

The second vulnerability, CVE-2021-30869, was a privilege escalation bug. This means that it could be used to run arbitrary code with the highest level of permissions possible when it should not actually have that level of access.

The first of these was patched on February 1, with the release of macOS Big Sur 11.2 and Safari 14.0.3. The latter would have fixed the problem on macOS Catalina (10.15) and macOS Mojave (10.14), if users had upgraded to Safari 14.

The second was apparently also fixed in Big Sur 11.2, on February 1, although it was not originally mentioned in the release notes. Mention of the fix was added on September 23, after Google alerted Apple to the issue and on the same day Apple released Security Update 2021-006 Catalina, to fix the issue in macOS Catalina.

Catalina wasn’t fixed for more than seven months?!

Yes, you heard that right. Apple knew about the vulnerability long before, and fixed it in macOS Big Sur, after the team who found it, Pangu, alerted Apple of the issue. Pangu went on to present their findings in April at the Zer0con security conference.

However, the same bug apparently existed in Catalina, which remained unpatched seven months after Apple released the patch for Big Sur, and more than five months after the details had been released at Zer0con. This allowed attackers to target individuals running Catalina and Safari 13 without detection. (According to TAG, more than 200 machines may have been targeted for infection at the time it discovered the campaign.)

There’s a lot that’s unclear about why this might have happened. Did Apple know that the bug affected Catalina, but chose not to patch it? Was the bug superficially different in Catalina, and thus was missed in a cursory investigation? Or was the bug completely different, but resulted in the same vulnerability? Only Apple could say.

I do find it highly suspicious that mention of this fix was left off of the Big Sur 11.2 release notes, and then added at the end at the same time the bug was fixed in Catalina. That would seem to suggest that it’s something that Apple already knew should have been fixed, or very quickly identified as being the same as the Big Sur bug.

Takeaways

There are a couple things that this incident illustrates quite plainly. First, this throws further weight behind what Joshua Long has taught us; that Apple can only be relied on to patch the absolute latest version of macOS, which is currently macOS Monterey (12). If you are using an older system, you do so at your own risk.

I personally have an older machine still on macOS Mojave, because upgrading to anything newer means I’d lose access to all my old 32-bit Steam games. However, since I’m aware that that system can no longer be considered secure, I limit what I do with it. Any web browsing and other online activities are done with my up-to-date devices, and since I’ve recently migrated to a newer machine, I’ll soon remove my personal data from the Mojave machine.

Second, the fact that this malware went undetected since at least 2019 is, unfortunately, a repeating pattern. There has been a lot of very tightly targeted nation state malware affecting Mac users, and because of the very limited number of victims, it’s hard to detect. Those managing business environments would do well to use some kind of EDR or other monitoring software, but what is an average person to do with their personal Macs?

Some steps you can take to avoid this kind of malware would include:

- Keeping your system and all your software fully up to date

- Be conscious of everything you open on your computer, and be sure you know exactly what it is before you do so

- Never install Adobe Flash Player, whether you think it’s legitimate or not!

- Use an ad blocker (malicious ads can be a source of malware) and some kind of protection against malicious sites, such as the free Malwarebytes Browser Guard

- If you engage in any “risky” activities, consider doing them from a burner device with no access to your data, such as a cheap Chromebook

- If you are a potential target of a hostile nation-state – such as a journalist or human rights activists critical of an oppressive regime, or a member of a group persecuted by a government (such as the Uyghur people in China) – consider consulting with a security professional

Malwarebytes for Mac detects this malware as OSX.CDDS.