French privacy watchdog, the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL), has hit Google with a 150 million euro fine and Facebook with a 60 million euro fine, because their websites—google.fr, youtube.com, and facebook.com—don’t make refusing cookies as easy as accepting them.

The CNIL carried out an online investigation after receiving complaints from users about the way cookies were handled on these sites. It found that while the sites offered buttons for allowing immediate acceptance of cookies, the sites didn’t implement an equivalent solution to let users refuse them. Several clicks were required to refuse all cookies, against a single one to accept them.

In addition to the fines, the companies have been given three months to provide Internet users in France with a way to refuse cookies that’s as simple as accepting them. If they don’t, the companies will have to pay a penalty of 100,000 euros for each day they delay.

GDPR

EU data protection regulators’ powers have increased significantly since the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took effect in May 2018. This EU law allows watchdogs to levy penalties of as much as 4% of a company’s annual global sales.

The restricted committee, the body in charge of sanctions, considered that the process regarding cookies affects the freedom of consent of Internet users and constitutes an infringement of the French Data Protection Act, which demands that it should be as easy to refuse cookies as to accept them.

Since March 31, 2021, when the deadline set for websites and mobile applications to comply with the new rules on cookies expired, the CNIL has adopted nearly 100 corrective measures (orders and sanctions) related to non-compliance with the legislation on cookies.

Responses

Google said in a statement that “people trust us to respect their right to privacy and keep them safe” and that the company understands its “responsibility to protect that trust and are committing to further changes and active work with the CNIL in light of this decision”.

Facebook said it’s reviewing the authority’s decision. Here it may be important to note that the CNIL fined Facebook Ireland Limited, rather than Facebook France, since the head office in Ireland presents itself as the data controller of the Facebook service in the European region.

The procedure

As an example we’ll follow the cookie management procedure for YouTube, which was one of the sites the CNIL objected against.

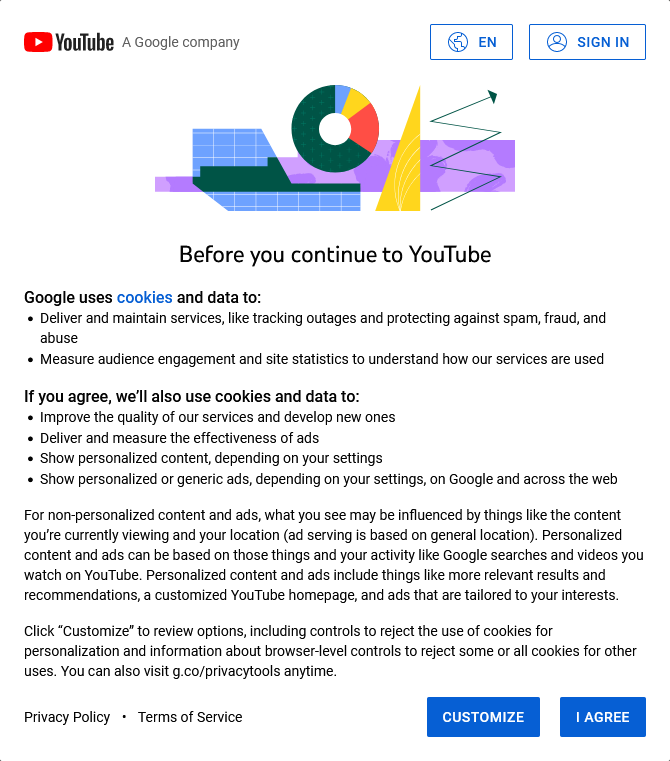

A first time visitor (or more precisely, someone without any cookies from a previous visit) is presented with this consent form:

The user’s options are to either accept all the cookies by clicking “I AGREE”, or to click “CUSTOMIZE”, which results in a multitude of choices to be made about search customization, YouTube History, ad personalization, managing cookies in your browser, and managing data Google Analytics collects on sites you visit.

The first three entries are simple On/Off settings.

The last parts however point to instructions or link to other sites, which in general come down to “You can change your browser settings to reject some or all cookies.”

This explains why the French watchdog objects to the skewed balance between accepting or rejecting cookies from these sites—the path to privacy is long and difficult.

The everlasting battle

Internet giants like Meta (Facebook) and Alphabet (Google) depend on advertising. Advertising represented 98% of Facebook’s $86 billion revenue in 2020, and more than 80% of Alphabet’s revenue comes from Google ads, which generated $147 billion in 2020.

Advertisers can bid on specific words and phrases, and target specific demographics, geographies or interests, and this ensures ads show up to relevant users at relavent times, or so the theory goes. To find out who the “relevant users” are ad companies gather massive amounts of information about users, and that is where our privacy comes into play.

The information is stored in giant databases about us, and the link between us and our database entries are the cookies in our browser. The cookie acts like an ID badge, you show it every time you hit a Google or Facebook page, or any time you hit a page that includes a like button, some Google Analytics code, or anything else loaded from a Google or Facebook domain.

Sometimes that’s useful. Logging in to a website would be impossible without a cookie “ID badge”—you’d have to provide your password on each and every page instead. But sometimes the ID badge is doing someting that’s useful to somebody else rather than you, such as allowing them to silently build a personal profile about you.

Luckily, sites rarely use one cookie for everything and typically use different cookies for different features. This is why YouTube customization options are so convoluted, and why adblockers and privacy plugins work at all. With a decent tool it’s possible to block or refuse the cookies you don’t like and keep the ones you do.

If you want to clear out everything and start again, take a look at our quick guide, How to clear cookies”.

Dark patterns

YouTube’s choice between “I agree” and “Customize” rather than “I agree” and “I don’t agree” is an example of a dark pattern, a desgin that subtely and deliberately nudges you in the direction of a choice that benefits the designer. They are everywhere on the web, and they’re a problem.

In June 2021, Malwarebytes Labs’ David Ruiz spoke to dark patterns expert Carey Parker on the Lock and Code podcast. To learn more about dark patterns and how to spot them, listen below.