Threat actors have rediscovered an old and little-used feature of web URLs, the innocuous @symbol we usually see in email addresses, and started using it to obscure links to their malicious websites.

Researchers from Perception Point noticed it being used in a cyberattack against multiple organizationrecently. While the attackers are still unknown, Perception Point traced them to an IP in Japan.

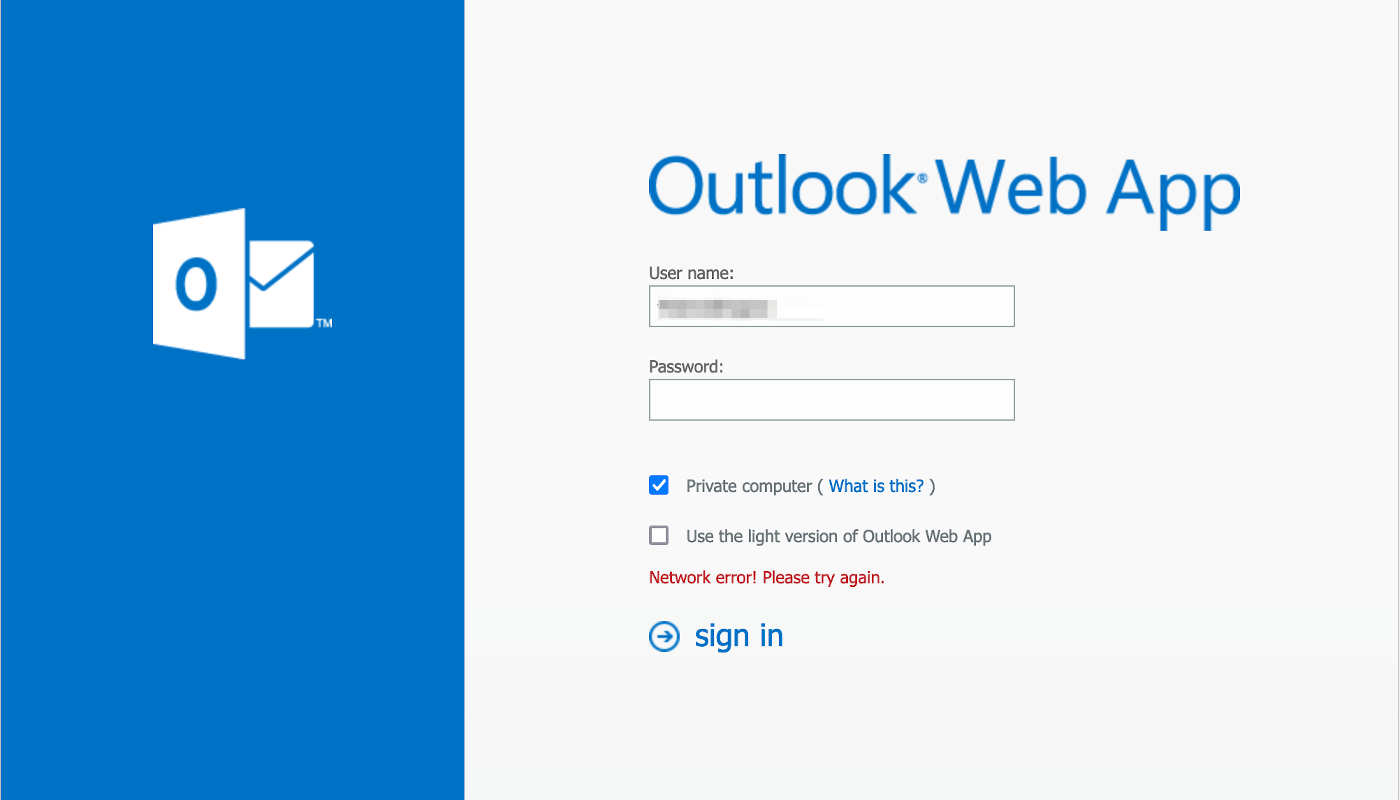

The attack started with a phishing email pretending to be from Microsoft, claiming the user has messages that have been embargoed as potential spam. (Using familiar, transactional messages from well-known brands like Microsoft has become a popular tactic for scammers, as a way to defeat spam filters and keen-eyed users.)

The message reads:

You have new 5 held messages.You can release all of your held messages and permit or block future emails the senders, or manage messages individually.If the recipient clicks any of the links in the email, they are directed to a phishing page made to look like an Outlook login page.

If the recipient follows the often-repeated advice to hover their pointer over the links before clicking them, to see where they go, they will see this weird-looking URL, and probably be none the wiser:

https://$%^&;****((@bit.ly/3vzLjtz#ZmluYW5jZUBuZ3BjYXAuY29t

This is almost certainly designed to bamboozle users, but to your computer it looks fine. As weird as this URL appears, it is actually valid and acceptable, and your browser will happily parse it for you.

Users who clicked on the link were passed through a chain of redirects before ending up at a phishing page that looks like the Outlook login screen.

Reading the URL

As weird as it looks, the URL in this phishing campaign sticks to the rules of what’s allowed in a web address. The part you see least often is the @symbol. RFC 3986refers to anything after https://and before the @symobl, highlighted below, as userinfo. This part of the URL is for passing authentication information like a username and password, but it is very rarely used, and is simply ignored as a so-called “opaque string” by many systems.

https://$%^&;****((@bit.ly/3vzLjtz#ZmluYW5jZUBuZ3BjYXAuY29t

The last part of the URL after the #is also ignored when you click the link. This is called the fragment identifier and it represents a piece of the destination page. The browser might use it to scroll to a section of the destination page, or it might be used to pass information to the destination page, but it plays no part in determining what the destination actually is.

https://bit.ly/3vzLjtz#ZmluYW5jZUBuZ3BjYXAuY29t

In this case the fragment ID—ZmluYW5jZUBuZ3BjYXAuY29t—appears to be a unique ID that identifies the email address the phish was sent to. If it’s removed, the link works but when you reach the final destination it simply shows a loading icon, perhaps to hide the site’s true intentions to accidental visitors or researchers.

What we are left with when we remove the parts that of the link that are ignored by the browser is a very ordinary-looking bit.ly link. Exactly the kind of thing you might think is suspicious in an email that says it’s from Microsoft.

https://bit.ly/3vzLjtz

As you probably know, bit.ly is a URL shortening service. The bit.ly link redirects users to another URL, likely used for tracking, which itself redirects users to the phishing page.

Does your browser support the @ symbol?

If you are one of the 2.6 billion people using Chrome, the answer is “yes”, URLs that use the @symbol work in Chrome and other Chromium-based browsers such as Vivaldi, Brave, and Microsoft Edge.

The latest version of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer doesn’t parse URLswith the @delimiter though.

Firefox and Firefox-based browsers, such as Tor and Pale Moon, are also affected.

And what about Safari?

According to Thomas Reed, Malwarebytes’ Director of Mac and Mobile, “This technique appears to work in Safari and all other major Mac browsers. Firefox will show a warning when attempting to visit such a link. Unfortunately, Safari—the most popular browser on macOS—does not display a warning and opens the link without objection, as does Chrome.”

Reed also points out that email software will often look for URLs in plain text emails and convert them to clickable links, but the @ symbol seems to prevent this. According to Reed: “The URL used by the phishing campaign does not become a clickable link by itself.” The links will still work in HTML emails, so this isn’t much of a barrier, just a feather in the cap of hold outs who insist on viewing their emails in plain text!

The wide support for the confusing and little-used @symbol could see it used more widely. In a Threat Post interview, Perception Point’s Vice President of Customer Success and Incident Response, Motti Elloul, predicted that this won’t be the last time we’ll see phishing attacks taking advantage of it.

“The technique has the potential to catch on quickly, because it’s very easy to execute,” he said. “In order to identify the technique and avoid the fallout from it slipping past security systems, security teams need to update their detection engines in order to double check the URL structure whenever @is included.”