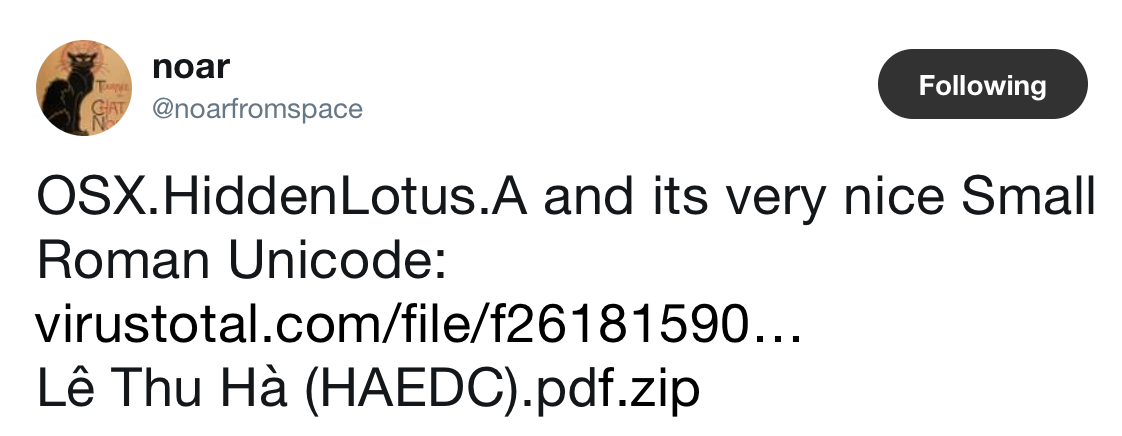

On November 30, Apple silently added a signature to the macOS XProtect anti-malware system for something called OSX.HiddenLotus.A. It was a mystery what HiddenLotus was until, later that same day, Arnaud Abbati found the sample and shared it with other security researchers on Twitter.

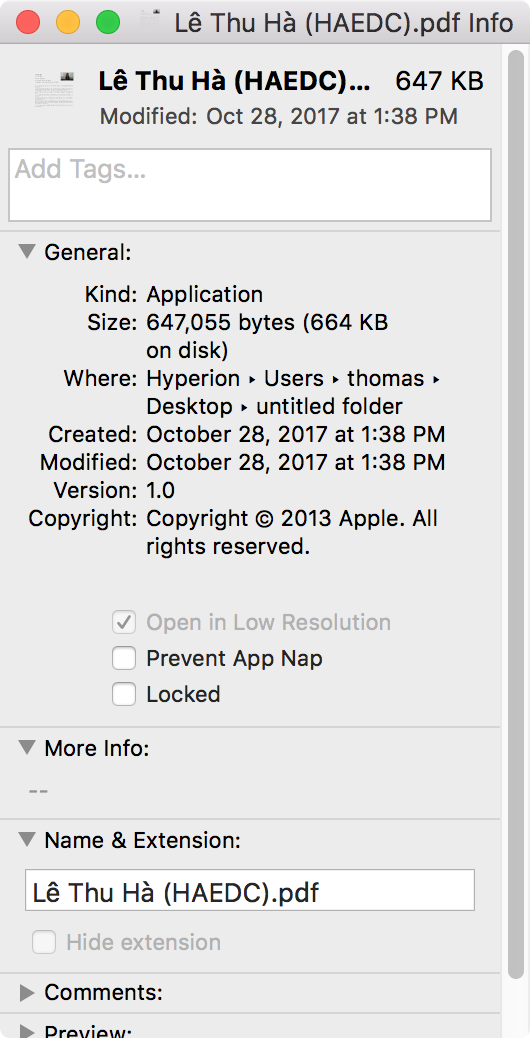

The HiddenLotus “dropper” is an application named Lê Thu Hà (HAEDC).pdf, using an old trick of disguising itself as a document—in this case, an Adobe Acrobat file.

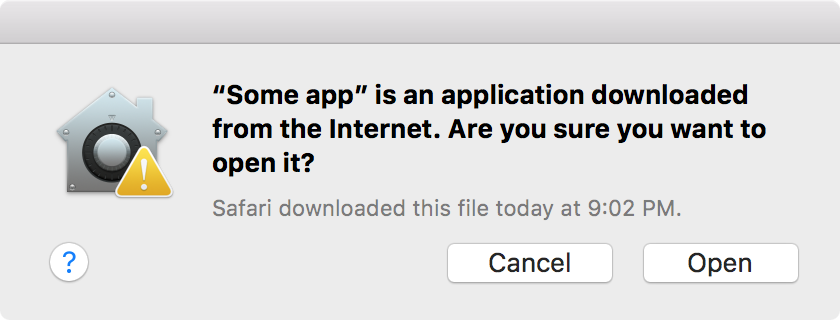

This is the same scheme that inspired the file quarantine feature in Mac OS X. Introduced in Leopard (Mac OS X 10.5), this feature tagged files downloaded from the Internet with a special piece of metadata to indicate that the file had been “quarantined.” Later, when the user tried to open the file, if it was an executable file of any kind, such as an application, the system would display a warning to the user.

The intent behind this feature was to ensure that the user knew that the file they were opening was an application, rather than a document. Even back in 2009, malicious apps were masquerading as documents. File quarantine was meant to combat this problem.

Malware authors have been using this trick ever since, despite file quarantine. Even earlier this year, repeated outbreaks of the Dok malware were distributed in the form of applications disguised as Microsoft Word documents.

So HiddenLotus didn’t seem all that interesting at first, other than as a new variant of the OceanLotus backdoor first seen being used to attack numerous facets of Chinese infrastructure. OceanLotus was last seen earlier this summer, disguised as a Microsoft Word document and targeting victims in Vietnam.

But there was something strange about HiddenLotus. Unlike past malware, this one didn’t have a hidden .app extension to indicate that it was an application. Instead, it actually had a .pdf extension. Yet the Finder somehow identified it as an application anyway.

This was quite puzzling. Further investigation did not turn up a hidden extension. There was also no sign of a trick like the one used by Janicab in 2013.

Janicab used the old fake document technique, being distributed as a file named (apparently) “RecentNews.ppa.pdf.” However, the use of an RLO (right-to-left override) character caused characters following it to be displayed as if they were part of a language meant to be read right-to-left, instead of left-to-right as in English.

In other words, Janicab’s real filename was actually “RecentNews.fdp.app,” but the presence of the RLO character after the first period in the name caused everything following to be displayed in reverse in the Finder.

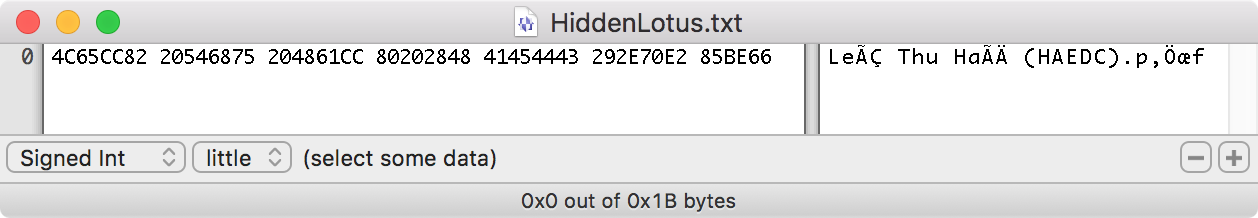

However, this deception was not used in HiddenLotus. Instead, it turned out that the ‘d’ in the .pdf extension was not actually a ‘d.’ Instead, it was the Roman numeral ‘D’ in lowercase, representing the number 500.

It was at this point that Abbati’s tweet referring to “its very nice small Roman Unicode” began to make sense. However, it was still unclear exactly what was going on, and how this special character allowed the malware to be treated as an application.

After further consultation with Abbati, it turned out that there’s something rather surprising about macOS: An application does not need to have a .app extension to be treated like an application.

An application on macOS is actually a folder with a special internal structure called a bundle. A folder with the right structure is still only a folder, but if you give it an .app extension, it instantly becomes an application. The Finder treats it as if it were a single file instead of a folder, and a double-click launches the application rather than opening the folder.

When double-clicking a file (or folder), LaunchServices will consider the extension first. If the extension is known, the item will be opened according to that extension. Thus, a file with a .txt extension will, by default, be opened with TextEdit. Some folders may be treated as documents, as in the case of the .aplibrary extension used for an Aperture library “file.” A folder with the .app extension will, assuming it has the right internal structure, be launched as an application.

A file with an unfamiliar extension is handled by asking the user what they want to do. Options are given to choose an application to open the file or to search the Mac App Store.

However, something strange happens when double-clicking a folder with an unknown extension. In this case, LaunchServices falls back on looking at the folder’s bundle structure (if any).

So what does this mean? The HiddenLotus dropper is a folder with the proper internal bundle structure to be an application, and it uses an extension of .pdf, where the ‘d’ is a Roman numeral, not a letter. Although this extension looks exactly the same as the one used for Adobe Acrobat files, it’s completely different, and there are no applications registered to handle that extension. Thus, the system will fall back on the bundle structure, treating the folder as an application, even though it does not have a telltale .app extension.

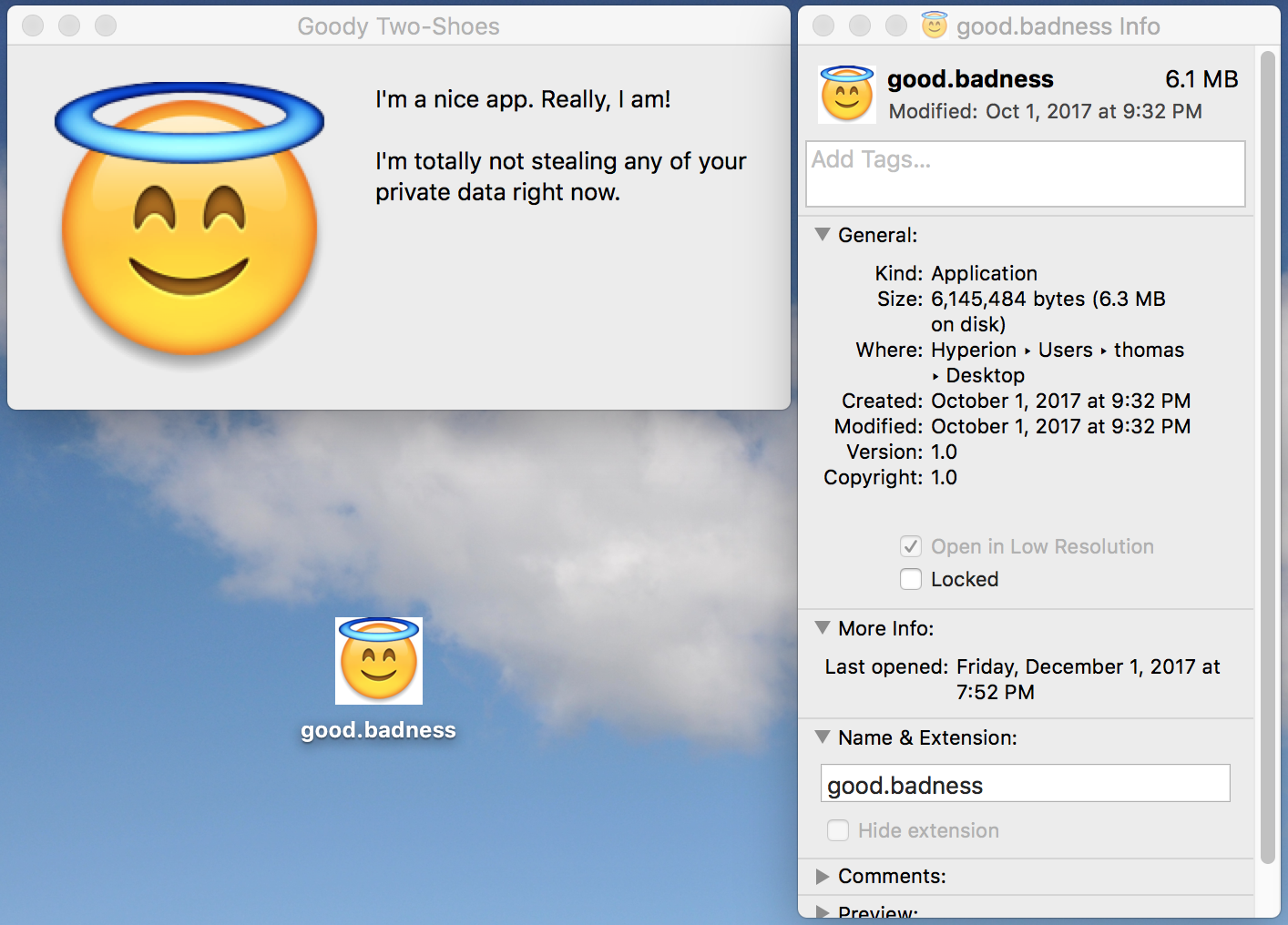

There is nothing particularly special about this .pdf extension (using a Roman numeral ‘d’) except that it is not already in use. Any other extension that is not in use will work just as well:

Of course, the example shown above wouldn’t fool anyone, it’s merely illustrative of the issue.

This means that there is an enormously large list of possible extensions, especially when Unicode characters are included. It is easily possible to construct extensions from Unicode characters that look exactly like other, normal extensions, yet are not the same. This means the same trick could be used to mimic a Word document (.doc), an Excel file (.xls), a Pages document (.pages), a Numbers document (.numbers), and so on.

This is a neat trick, but it’s still not going to get past file quarantine. The system will alert you that what you’re trying to open is an application. Unless, of course, what you are opening was downloaded via an application that does not use the APIs that properly set the quarantine flag on the file, as is the case for some torrent apps.

Ultimately, it’s very unlikely that this trick is going to have any kind of significant impact on the Mac threat landscape. It’s probable that we will see it used again in the future, but the risk to the average user is not significantly higher than in the case of any other fake document malware.

More than anything else, this trick opens our eyes to an interesting aspect of how macOS identifies and launches applications.

If you think you may have encountered this malware, Malwarebytes for Mac will protect against it, and will scan for and remove it, if present, for free.