Every year on Data Privacy Day, we’re greeted with countless arguments about the absolute merits of data privacy (protections good, invasions bad), but we rarely see a faithful, factual accounting for the biggest data privacy conundrum facing billions of people every single day: Should parents invade the data privacy of their children and digitally track their activity in order to provide them with a little more safety?

On Data Privacy Day this year, we decided to investigate the issue ourselves, and we found that, for the majority of parents we asked, the answer was a simple, and at times disappointing, “Yes.”

But there’s some nuance here, as parents revealed that their invasions of data privacy against their children typically happened when their children began to face new threats, whether online or in the real world. If a kid is old enough to enter a URL into a web browser, then they’re old enough to have that web browsing activity tracked, our parents revealed, and the same goes for opening a social media account, watching YouTube, and potentially just moving about the neighborhood, which could be tracked through GPS locations.

Privacy invasions, then, are reactionary, and not planned. They are a response to a changing, frightening world that every parent has faced before, but that only parents today can push back against through the use of modern, digital tracking.

But parents should understand the risks that come with this digital tracking.

Multiple surveys and research studies have shown that increased digital surveillance of children often results in more strained relationships between parents and their children. Further, as our own survey showed, parents more commonly monitor more than one type of activity from their children, which could lead to those same parents searching for a single, “all-in-one” app to track a child’s location, text messages, browsing history, and more.

Those apps do exist, and, depending on their capabilities, are indistinguishable from the pernicious digital threat known as stalkerware. Stalkerware-type apps, which Malwarebytes detects to protect users from harm, provide many of the same invasive features that some parents might unknowingly consider attractive—a window into browsing history and location, but also unfettered access to text messages, photos, and videos, and worrying capabilities to record phone calls (sometimes illegally) and to secretly use a phone’s camera and microphone.

Our survey

To learn more about what parents believe, earlier this month we asked our newsletter subscribers to fill in a short, anonymous survey about the monitoring they do of their kids.

We asked parents if they monitored their children’s location (GPS), web browsing, computer games, YouTube activity, social media posts, email, or WhatsApp or other message apps; the ages they started and stopped the monitoring; whether they told their children they were being monitored or not; and the age they thought children should be allowed to start using social media.

As with any online survey, you should understand the potential biases of the population involved: The respondents were a self-selecting group of individuals who care enough about technology, security, and privacy to have subscribed to a newsletter about it, and to respond to a survey about parental attitudes to electronic monitoring.

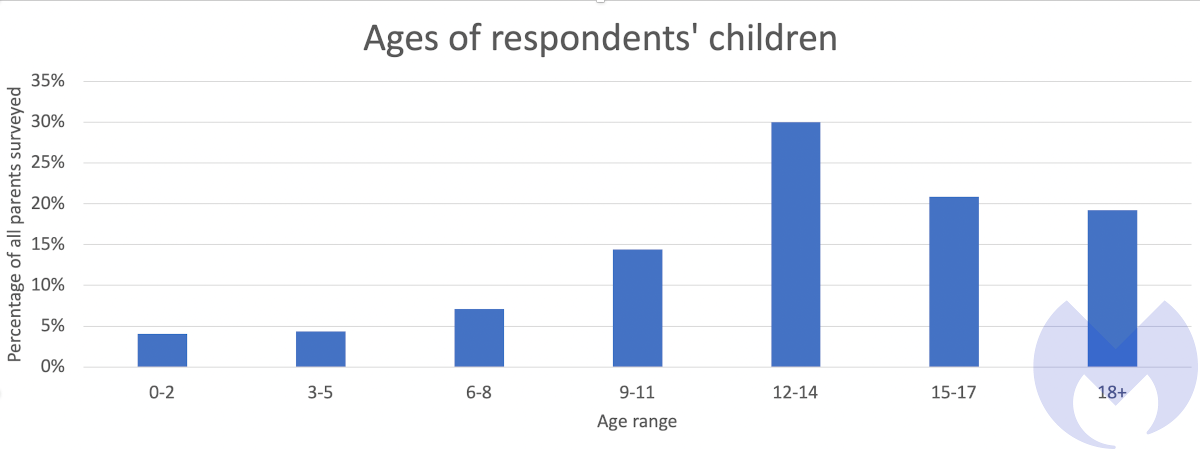

899 parents filled in the survey, and most of them had children aged nine years old or older.

Digital tracking is too common

The survey suggests that using some form of electronic monitoring to keep tabs on children is a common practice.

84% of our respondents admitted to some form of electronic monitoring of their children, 70% used at least one form of monitoring they had told their child about, and 36% used at least one form of monitoring they had not told their child about.

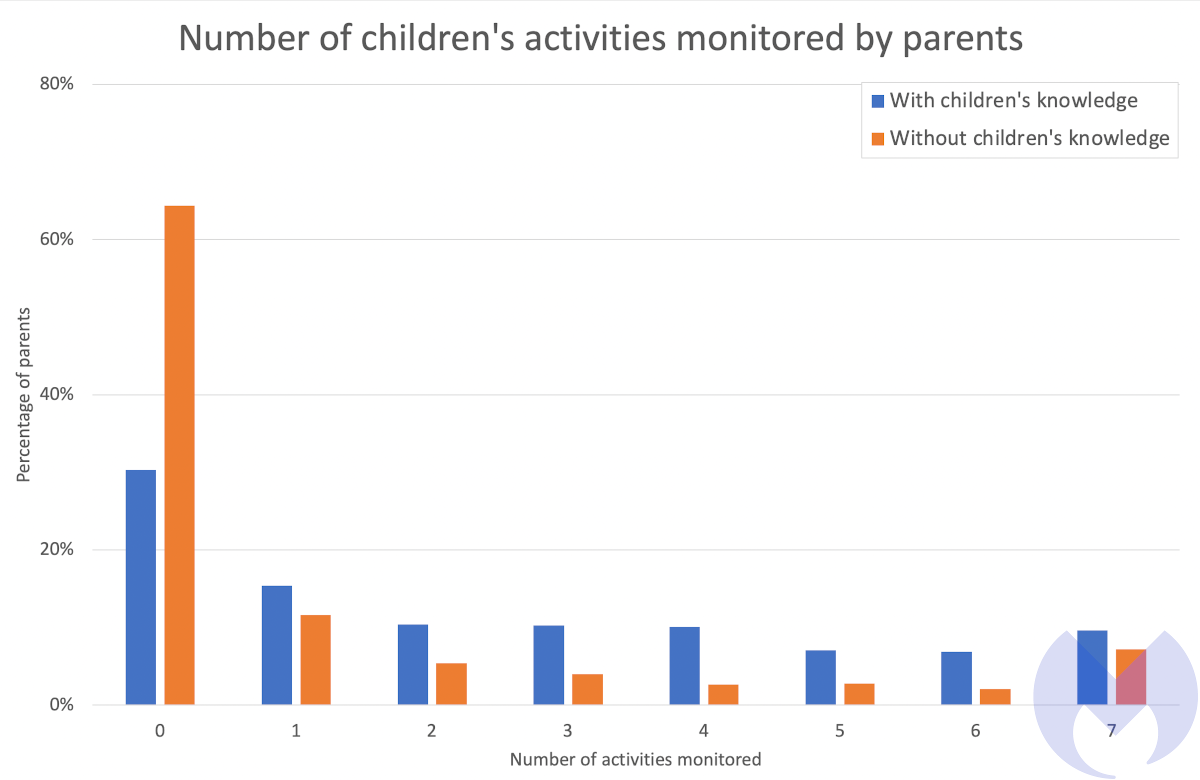

Parents who monitor tend to use more than one kind of monitoring, whether they tell their children or not. 54% of parents use at least two forms of monitoring with their child’s knowledge, and 24% of parents use at least two forms of monitoring without their child’s knowledge.

As you would expect, the number of parents monitoring multiple activities declines as the number of activities increases—more parents monitor one activity than two, more monitor two than three, and so on. There is one exception though. About 7% of the parents we surveyed monitored all seven of the different activites we asked about without their child’s knowledge.

What parents monitor

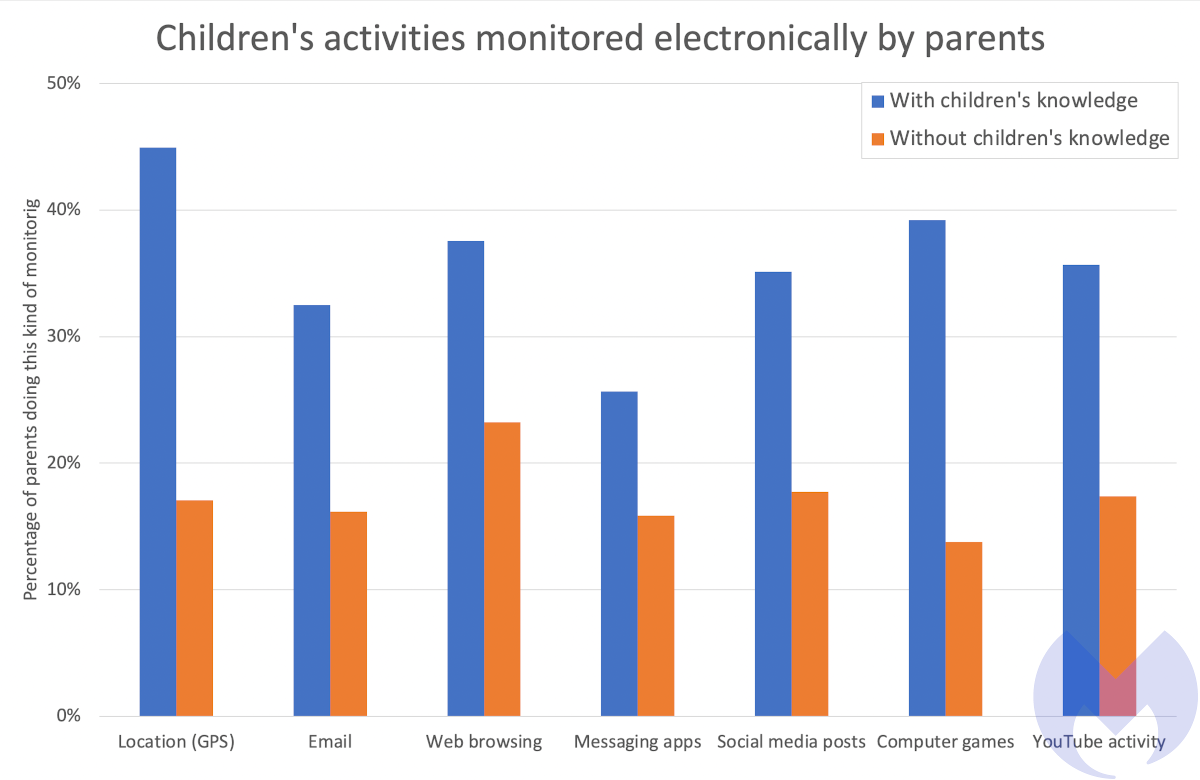

There is surprisingly little variation in the amount of parents monitoring each activity we asked about, with every individual activity being monitored by between about 30% and 40% of parents. The most common thing for parents to monitor electronically was their child’s physical location (GPS), and the least common thing to monitor was messaging apps. This may reflect where parents see the most potential harm, or it may simply reflect how easy some kinds of monitoring are compared to others. Of the activities we surveyed parents about, GPS is probably the easiest thing to monitor, and messaging apps the hardest.

This is largely because of technical capabilities. Modern messaging apps including iMessage and WhatsApp offer something called “end-to-end encryption” between users, which technologically makes it so that messages are only legible on the devices between the users sending and receiving those messages. Any piece of software that alleges that it can crack into these messages is either vastly over-promising its capabilities or it is veering closer into the world of international espionage. This is why “monitoring” a child’s text messages might best be interpreted as a parent asking to view the messages on the device itself, whereas retrieving those messages remotely from another computer could more accurately be called “spying.”

Separately, almost a quarter of the parents surveyed said they monitored their children’s web browsing without telling them.

When monitoring starts

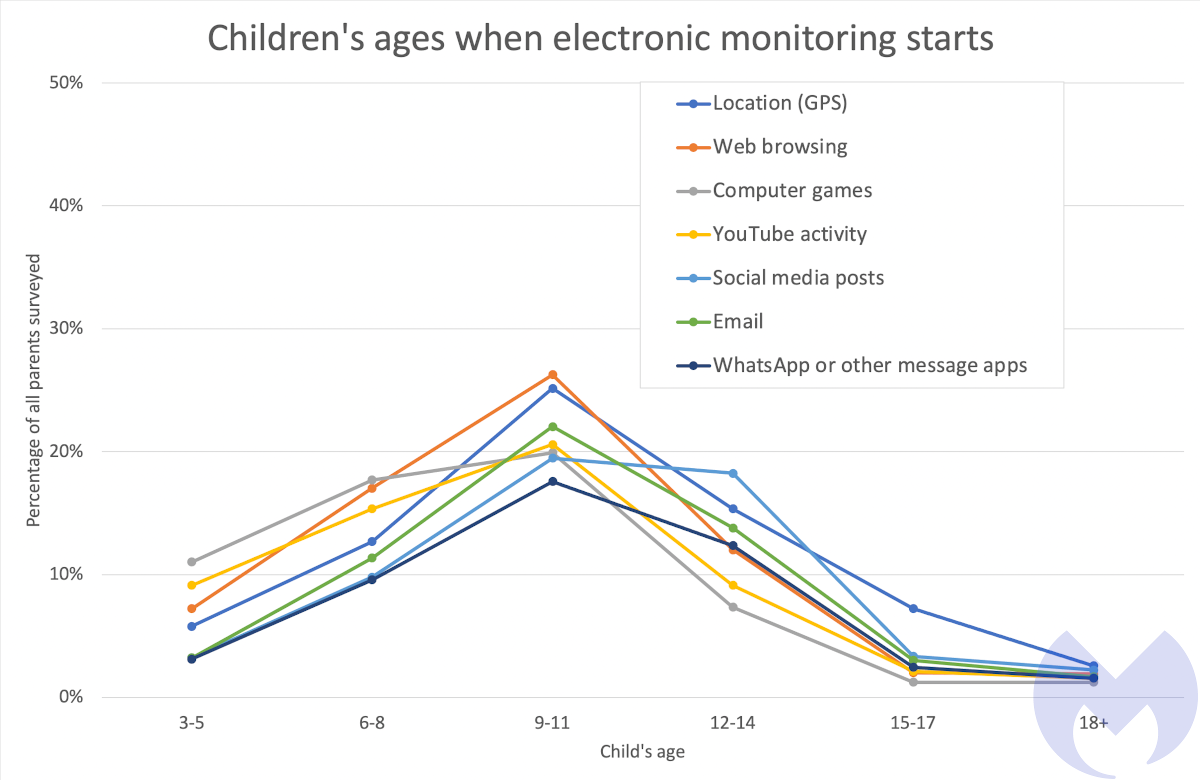

As you might expect, the age at which parents start different types of electronic monitoring tends to reflect the ages at which children gain some level of independence in different areas of their lives.

Some parents start using electronic monitoring when their children are 3-5 years old, and others wait until their children are in their late teens, but the most common time to start electronic monitoring is when children are between 9 and 11, although it skews a little younger for computer games, and a little older for social media.

When monitoring ends

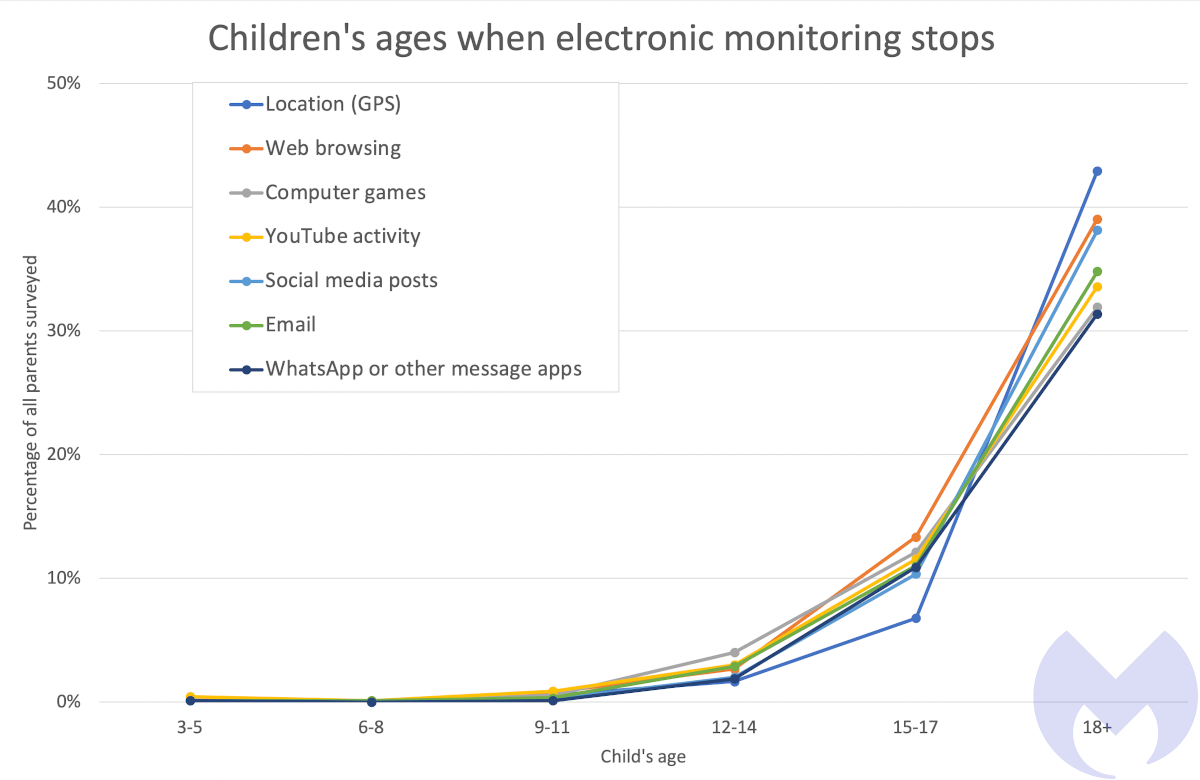

While there is lots of variation in the age when monitoring starts, there isn’t in when it stops. Parents, it seems, are very unlikely to stop monitoring their children before their eighteenth birthday.

Social media

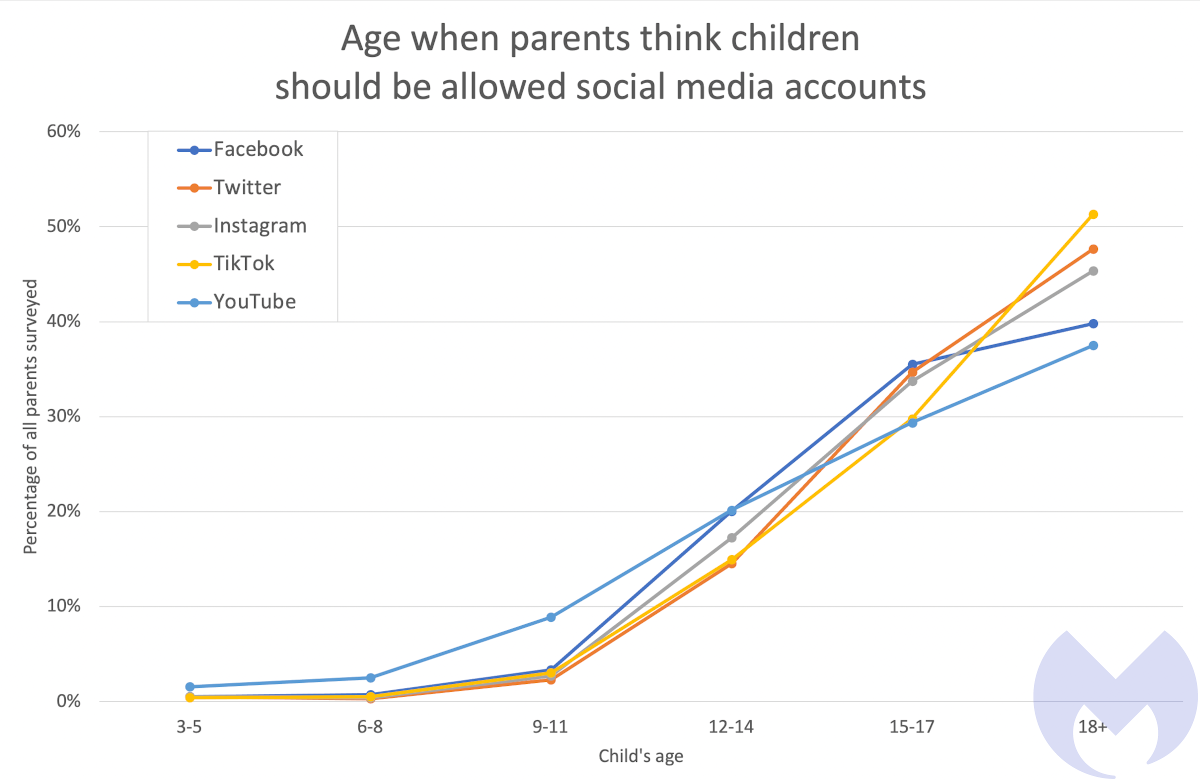

Our respondents were also aksed when they thought children should be allowed to open Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube accounts.

Most of the popular social media platforms have a minimum age limit of 13 years, but only about 30% of our respondents thought that children were old enough to open a social media account at that age or younger. While more parents thought 15-17 was a better age, the biggest cohort by far—between about 40 and 50% of all the parents surveyed, depending on the platform—thought the minimum age should be 18 or older.

YouTube, which is popular with kids and has very different functionality than the other platforms in our list, skewed a little younger. And TikTok, the newest platform and perhaps the least well understood by parents, attracted the most caution, with more than 50% of parents putting saying children should be 18 years or older to open an account.

What should you do?

Malwarebytes is, first and foremost, a cybersecurity company, not a parenting forum. Through our work in fighting the threat of stalkerware—which goes back years—we’ve learned that several of these apps often disguise themselves as “family friendly” tools, which might make them less likely to be caught by both law enforcement and cybersecurity vendors like us and others in the Coalition Against Stalkerware.

When Malwarebytes Labs last reported on this issue, multiple experts in child privacy and intimate partner surveillance agreed on one thing: If you’re going to monitor a child’s activity, speak with them about it first. Diana Freed, a PhD student at the Intimate Partner Violence tech research lab led by Cornell Tech faculty, recommended that parents have a separate conversation for every type of monitoring they want to introduce, too.

“You can openly say [to a child] ‘I am going to start looking at your location because we’re concerned and this is how we’re going to do it. In terms of the child’s privacy, have a conversation on the concerns and why you’re doing it, what the app you’re putting on their phone will do, what information you’ll know.”

It is also important to understand the difference between “monitoring” and “spying.” Several apps on the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store provide limited monitoring functionality for things like location, while never allowing parents a full view into their children’s private lives. Sometimes the difference comes down to one question: Does your kid know about it?

Conclusions

For our survey respondents, using electronic monitoring to keep tabs on their children is normal, and monitoring children without their knowledge is common. Parents that monitor their children tend to employ more than one method, and the most common age for each form of monitoring to start is—very roughly—the point where we might expect children to be given some independence in that area.

Most of the parents we surveyed think that children should be at least 15 before they open social media accounts, with 18+ the preferred age for about half of all parents. This puts social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter on a par with common minimum ages for things like sexual intercourse, driving, smoking, and drinking: Potantially dangerous activities reserved for children on the cusp of adulthood.

In short, our survey suggests that when it comes to privacy in the family, parents are conservative (in the “small c”, apolitical sense of the word) in their attitudes. Our survey says nothing about parents’ concern for children’s privacy in general, but it suggests that providing children with a space in which to be private from their parents plays a distant second fiddle to the responsibility parents feel for keeping them safe.