Last week, the disclosure by multiple teams from Graz and Pennsylvania University, Rambus, Data61, Cyberus Technology, and Google Project Zero of vulnerabilities under the aliases Meltdown and Spectre rocked the security world, sending vendors scurrying to create patches, if at all possible, and laying bare a design flaw in nearly all modern processors.

The fallout from these revelations continues to take shape, as new information on the vulnerabilities and the difficulties with patching them comes to light daily. In the days since Meltdown and Spectre have been made public, we’ve tracked which elements of the design flaw, known as speculative execution, are vulnerable and how different vendors are handling the patching process. By examining the applied patches’ impact against one of our own products, Adwcleaner, we found that they are, indeed, causing increases in CPU usage, which could result in higher costs for individuals billed by Cloud providers accordingly.

What is speculative execution?

Speculative execution is an effective optimization technique used by most modern processors to determine where code is likely to go next. Hence, when it encounters a conditional branch instruction, the processor makes a guess for which branch might be executed based on the previous branches’ processing history. It then speculatively executes instructions until the original condition is known to be true or false. If the latter, the pending instructions are abandoned, and the processor reloads its state based on what it determines to be the correct execution path.

The issue with this behaviour and the way it’s currently implemented in numerous chips is that when the processor makes a wrong guess, it has already speculatively executed a few instructions. These are saved in cache, even if they are from the invalid branch. Spectre and Meltdown take advantage of this situation by comparing the loading time of two variables, determining if one has been loaded during the speculative execution, and deducing its value.

As explained in our post last week, the potential danger of an attack using these vulnerabilities includes being able to read “secured” memory belonging to a process. This can do things like reveal personally identifiable information, banking information, and of course usernames and passwords. On cloud environment, these vulnerabilities allow extracting data from the host and other VMs.

Example of speculative execution

Using the Project Zero example below, the process will evaluate the condition if(untrusted_offset_from_caller < arr1->length) at a later time, and start a speculative execution of both branches, leading to two different index2 values. This example corresponds to variant 1 of Spectre (CVE-2017-5753) and works on most Intel, AMD, ARM, and IBM CPUs.

[code language=”cpp”] struct array { unsigned long length; unsigned char data[]; }; struct array *arr1 = …; /* small array */ struct array *arr2 = …; /* array of size 0x400 */ /* >0x400 (OUT OF BOUNDS!) */ unsigned long untrusted_offset_from_caller = …; if (untrusted_offset_from_caller < arr1->length) { unsigned char value = arr1->data[untrusted_offset_from_caller]; unsigned long index2 = ((value&1)*0x100)+0x200; if (index2 < arr2->length) { unsigned char value2 = arr2->data[index2]; }[/code]

If the processor predicts that the condition is true, value will load:

[code language=”cpp”] unsigned char value = arr1->data[untrusted_offset_from_caller]; [/code]

Based on value, it’s possible to load index2, which can be 0x200 or 0x300 due to the bitwise operation:

[code language=”cpp”] unsigned long index2 = ((value&1)*0x100)+0x200; [/code]

The second condition is then executed and the last instruction loads value2 as arr2->data[0x200] or arr2->data[0x300].

Once the initial condition has been evaluated and the processor notices that the execution flow above is wrong, the value of value2 stays in the L1 cache. It’s then possible to compare the loading time of arr2->data[0x200] and arr2->data[0x300], and deduce which one has been evaluated during the speculative execution. From there, it’s easy to figure out related variables: Here the value of arr1->data[untrusted_offset_from_caller] is a value that shouldn’t be possible to retrieve according to the expected code flow, since it allows to leak out-of-bound memory.

In order to exploit this behaviour, the code pattern above has to be present on the victim’s machine. As detailed in Jann Horn’s writeup, a locally installed software, a JIT (Javascript is a particularly interesting candidate), or an interpreter (he used eBPF) meet the requirements.

Four variants

While it was initially reported that Spectre and Meltdown correspond to three vulnerabilities, four variants actually exist:

- Spectre:

- Variant 1 – CVE-2017-5753

- Variant 2 – CVE-2017-5715

- Meltdown:

- Variant 3 – CVE-2017-5754

- Variant 3a – /

Variants 1 and 2 of Spectre impact Intel, IBM, ARM, and AMD CPUs. Meltdown appears to be exclusive to Intel CPUs, and allows attackers to read privileged memory from an unprivileged context, still using the speculative execution feature. Its variant 3a is exploitable on a few ARM CPUs only.

The fact that these vulnerabilities impact the CPUs themselves make them difficult to patch. A software-only solution may bring important performance issues, as would a hardware-only fix. Thus, various hardware vendors have been working together in the past months working on fixes. However, while major players like Amazon and Microsoft got early access to the vulnerabilities reports, other providers did not. They discovered the vulnerabilities at the same time as the disclosure on January 3.

Vendors band together

Those who weren’t in on the secret formed a task group with other providers in order to exchange information and to pressure hardware manufacturers. Scaleway, OVH, Linode, Packet, Digital Ocean, Vultr, Nexcess, and prgmr.com have been part of it, later joined by Amazon, Tata Communications, and also parts of the RedHat and Ubuntu teams. On January 9, part of the researchers (Moritz Lipp, Daniel Gruss, Michael Schwarz from the Graz University of Technology) who discovered the vulnerabilities also joined in.

Some Open-Source developers also explained that they had not received any information prior the public disclosure, but were actively working on providing patches.

We have received *no* non-public information. I’ve seen posts elsewhere by other *BSD people implying that they receive little or no prior warning, so I have no reason to believe this was specific to OpenBSD and/or our philosophy.

Mitigations began to land upstream in the Linux kernel shortly after the public disclosure to address the vulnerabilities separately. Some require a hardware-vendor-issued microcode to be applied to the processor in order to make the software patch effective. Most of these patches are simply workarounds, however, to avoid making the CPU behave as explained above. We may expect some hardware change in future generations of processors at some point, but there’s no easy, quick fix for now.

Available patches for hardware and OSes

The upstream Linux patch for Meltdown (variants 3 and 3a) takes advantage of KPTI (Kernel Page Table Isolation) and has been backported to Linux 4.14, 4.9 and 4.4. It’s is available in most distribution’s official kernels. Debian has shipped it in most releases, as RedHat has done. Ubuntu published theirs a few hours ago, although some critical issues have been discovered and quickly addressed. Tails published an update, too. The patches for ARM64 haven’t been merged yet but are expected to be merged later.

Variant 1 (Spectre) requires changes to compilers behaviour and Intel suggests adding LFENCE (see 3.1 Bounds Check Bypass Mitigation; other vendors have other suggestions) as a barrier to stop speculation in specific places. This means that the kernel and software has to be recompiled in order to avoid making the processor use the speculative execution when it’s problematic. Again, although we may expect hardware changes in future generations of Intel chips, we can’t expect this to happen for a long time.

Variant 2 (also Spectre) requires both a microcode patch from CPU vendors and a patch from the kernel to leverage IBRS (Indirect Branch Speculation Feature), STIBP, and IBPB. Another suggestion called “retpoline” has been introduced by Paul Turner from Google and is also being implemented in various compilers, including GCC and LLVM, even though some questions still remain about its efficiency on certain CPU models.

| Vulnerability | (Linux) Software mitigation | Hardware mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Meltdown (3 & 3a) | KPTI | Not needed |

| Spectre 1 | n/a | n/a |

| Spectre 2 | IBRS / Retpoline | Microcode |

Proprietary vendors have also published several updates:

- Apple addressed the two Meltdown variants in iOS 11.2, macOS 10.13.2, and tvOS 11.2. Spectre is being mitigated in iOS 11.2.2 and the macOS 10.13.2 Supplemental Update, even though only recompiled software are an effective mitigation for variant 1.

- Google has included some mitigations for the three variants in its Android Security Bulletin on January 5. Note that further mitigations are expected in next month’s updates, especially a kernel with KPTI.

Regarding Microsoft, the process has been bumpier. They’ve released various fixes for the platform, but made several requirements for the patches for Spectre and Meltdown to be effective:

- If an antivirus solution is registered in the Windows Security Center, it needs to set the following registry key:

[code]

Key=”HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE” Subkey=”SOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionQualityCompat” Value=”cadca5fe-87d3-4b96-b7fb-a231484277cc” Type=”REG_DWORD” Data=”0x00000000”

[/code]

Only then can the January Patch Tuesday patch be applied. Note that Malwarebytes users have been able to successfully receive the patch since its publication.

2. As pointed out by Kevin Beaumont, a specific manipulation must be done on Windows Server to apply the patch and enable it. After creating the following keys and restarting the host, the mitigation should be in place:

[code] reg add “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINESYSTEMCurrentControlSetControlSession ManagerMemory Management” /v FeatureSettingsOverride /t REG_DWORD /d 0 /f reg add “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINESYSTEMCurrentControlSetControlSession ManagerMemory Management” /v FeatureSettingsOverrideMask /t REG_DWORD /d 3 /f reg add “HKLMSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindows NTCurrentVersionVirtualization” /v MinVmVersionForCpuBasedMitigations /t REG_SZ /d “1.0” /f [/code]

A few moments later, users began to report computers running with AMD processors becoming unbootable after applying the patch. Microsoft has stopped delivering the patch to those configurations while working with AMD to find a solution.

Available software patches

Apart from hardware manufacturers and OS vendors, software editors have also been quick to mitigate the exploitation of Spectre. Browser vendors and virtualization solutions are particularly exposed to these vulnerabilities and have been the fastest to respond.

- Xen published an advisory sharing details about the vulnerabilities in its hypervisor’s scope alongside a documentation page explaining how to mitigate.

- Mozilla released Firefox 57.0.4 soon after publishing an article explaining how they managed to exploit Spectre remotely using Javascript and WebAssembly. This update makes time source less precise, thus making the exploitation a lot more unreliable while more in-depth fixes are engineered.

- Google Chrome followed shortly after with an explanatory article about how Spectre could be exploited using WebKit’s JavascriptCore and listing the upcoming mitigations in Webkit.

Numerous Proof of Concepts have been published to demonstrate the exploitation of the different variants, from reconstructing an image to applying it against a specifically-crafted Intel SGX enclave. It’s also possible to test if mitigations are in place: Microsoft released a solution that can be used remotely based on the new PowerShell SpeculationControl module, and several solutions are available on Linux-based OSes.

Patches impact on AdwCleaner’s infrastructure

Disclaimer: The following is not a benchmark, but feedback based on what we have observed in our hardware environment and software stack. The observed behaviour is highly dependent on the workload, and there may be no changes observed in yours.

As part of our security process, we’ve applied fixes as soon as they were made available by our distributions and hosting providers. We were expecting some performance increase, especially on AdwCleaner storage backend, but it was hard to quantify.

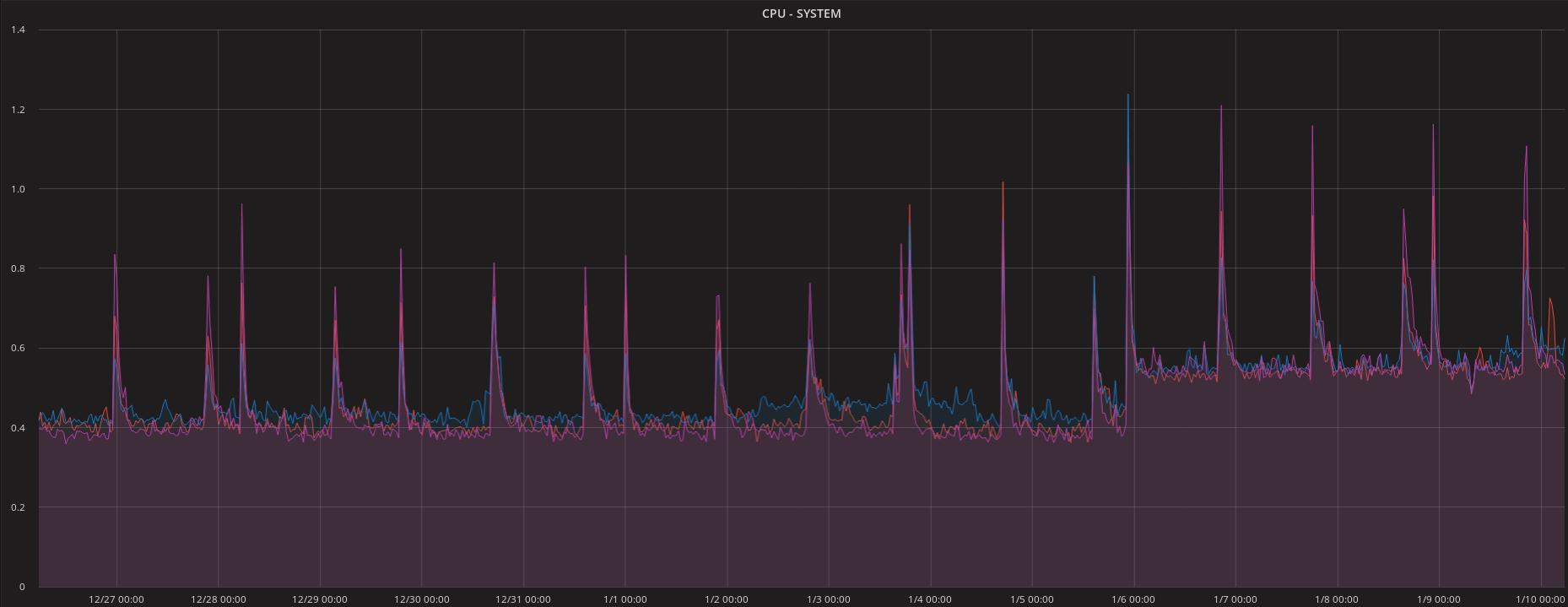

CPU load before and after KPTI patch on AdwCleaner storage backend.

After applying the new Linux kernel with the KPTI backport, we’ve observed a 10 to 15 percent increase of CPU usage. (We applied the patch slightly before 00:00 UTC on January 6). These servers do not take advantage of PCID, which could make the difference in performance less visible. As this usage increase appears to be the new baseline for some time, this is likely to at least temporary lead to important cost increases for users of providers billing based on CPU usage, although some providers are reported working with severely impacted customers.

As the situation still evolves quickly every day, some updates may be added to both the original story and this blogpost.

Particularly interesting literature: