Yesterday, Mike from the mailroom came up and asked whether I knew anyone called “Simon Smith.” He received an envelope addressed to our company and to the attention of Mr. Smith, but there was no one by that name on his list of employees.

It wasn’t on mine either and HR was unaware of a person by that name ever employed here. Nor did we expect anyone by that name to start working here. So, the package was a mystery and I told Mike to return it to sender, which he did.

A few weeks later, our firm was hit by ransomware.

Who would’ve ventured a guess the two were related?

This didn’t happen to Malwarebytes, of course. But it’s a scenario that has played out in other organizations in an attack vector known as war shipping.

When the goal of the sender is to have a parcel stay inside an office building for a few days, then a well-informed threat actor could send the parcel to the attention of a recently fired employee, an employee that just went on vacation, or even a non-existent employee. And when it comes to war shipping, a few days behind enemy lines is usually enough.

What is war shipping?

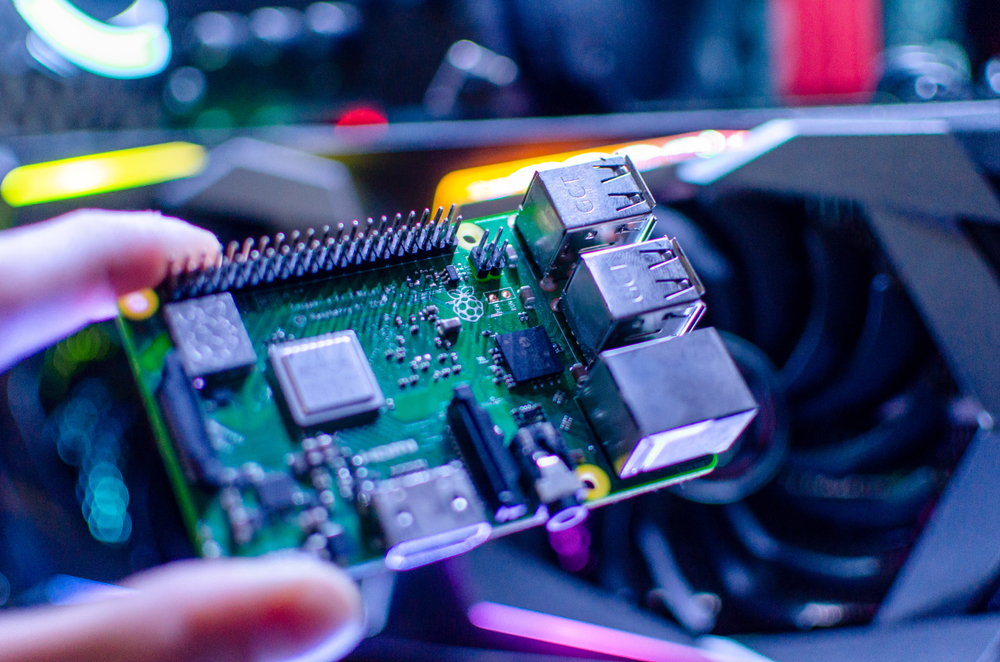

War shipping is a method of business espionage where the attacker ships a small device to the target company. The small device is usually a rigged Raspberry-Pi with a connected Wi-Fi card, a GPS receiver, and a battery—all in miniature versions. The installed software is especially designed to search for Wi-Fi networks and try to compromise them.

Per usual, the device also includes some form of location tracker, so the attacker will know where it is, and when to deploy the attack (i.e. when the target location is reached). For example, threat actors typically wouldn’t want to hack the postal services, so the device lays dormant until it reaches its target destination. This allows for the device to go undetected until its “hacking” activity raises red flags.

A device behind enemy lines can also be used to set up a malicious Wi-Fi access point to perform Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks.

Recommended reading: When three isn’t a crowd: Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks explained

Where does the name “war shipping” come from?

Years ago, driving around in your car with a laptop looking for open Wi-Fi networks was dubbed “war driving” after the term “war dialing,” which was first introduced in the movie WarGames. Another similar term, war walking, employs a similar method, but the attacker uses a handheld device stashed in a suitcase or other luggage.

War shipping software

Software that can be used in war shipping could be customized for advanced attacks, but for less financially stable attackers, there are standard software packages like Kismet. Kismet is a console-based wireless network detector, sniffer, and intrusion detection system. It identifies networks by passively sniffing, and it can even discover hidden networks if they are in use. It can automatically detect network IP blocks by sniffing TCP, UDP, ARP, and DHCP packets, log traffic in several easy-to-analyze formats, and even plot-detected networks and estimated ranges on downloaded maps.

Fluxion is a Linux-based script specialized in performing “evil twin” man-in-the-middle attacks. It scans the network and performs a de-authentication attack on clients in order to capture the WPA handshake when they re-connect. Then it launches an Evil Twin AP, a fake access point, and de-authenticates clients again, but this time to connect to its own Evil Twin AP.

Fluxion sets up a DHCP and DNS server to make sure the requests go through the Evil Twin AP. With these preparations in place, it sets up a web portal, including an SSL if you like, where people can enter their Wi-Fi password. Once you have a valid password, this part of the attack stops.

Fluxion is just one example of a MitM attack, but it’s usually able to provide the attacker with a valid Wi-Fi password within 30 minutes. From there, other software can be deployed that uses the validated password to further infiltrate the target’s network.

Is war shipping actively used?

Funny you should ask. The Dutch ministry of Justice and Safety said it was not aware of any active usage. But since we do know that red teams are using war shipping methods, is there any reason to assume that real cybercriminals wouldn’t? They probably are, but we just haven’t found them out yet.

The method of war shipping has been known for a few years, but only recently surfaced in the news when IBM’s X-Force Red team presented at BlackHat USA 2019 on what they were able to do with a war driving device that cost less than $100.

So why is war shipping important now?

As we have seen, the introduction of smaller chips and more effective (also smaller) batteries has taken war shipping to level where concealing a war shipping device has become easy. This opens up the number of options that attackers have to get the device into the desired place. And they can adapt the installed software to perform the task of spying for the information that the attackers are after.

Should the attacker want to buy himself some more time, the “hacking device” can be built into a present that is likely to get a place on a desk in the targeted office. This might allow the war shipping device to extend its active timeline and keep at it until the battery runs out.

Having access to your Wi-Fi can provide cybercriminals with vital information. Whether they are going to use that for industrial espionage, data mining, or a ransomware attack doesn’t matter. You are not going to be happy about it.

Countermeasures

Preventing war shipping will become an increasingly difficult task as devices get smaller and maybe even smarter. Here are some suggestions:

- A metal detector in the mailroom: This might be an option if you can expect your company to be a target of sophisticated attacks, but raising the security perimeter of your building(s) to the level of an airport is bound to hinder day-to-day operations.

- Network security systems: For example, an intrusion detection system (IDS), which is a device or software application that monitors a network or systems for malicious activity or policy violations.

- Password protect file sharing and other important shares: By doing this, a leaked or stolen Wi-Fi password will not give an attacker unlimited access to your resources.

- Use multi-factor authentication to let your employees log in to Wi-Fi Captive Portal. Auto-connect is user-friendly but not as secure.

One could argue that organizations should not use Wi-Fi at all, but I think our society has long since passed that stage. Maybe a few organizations with a large bullseye on their back could be convinced to consider this option, but most others will shy away from going back to a fully wired network. Instead, ensuring optimum protection of Wi-Fi networks will prevent even the more inventive attacks like war shipping.

Stay safe, everyone!