How do threat actors manage to get their sites and files hosted on legitimate providers’ servers? I have asked myself this question many times, and many times thought, “The threat actors pay for it, and for some companies, money is all that matters.”

But is it really that simple? I decided to find out.

I asked some companies, as well as some of my co-workers who are involved with site takedowns on a regular basis, about their experiences.

I conversed with William Tsing who is, among others, responsible for infringements on the Malwarebytes brand; Steven Burn, our Website Protection Team Lead; and with a spokesperson of International Card Services B.V. (ICS), the company behind the well-known Visa and Mastercard credit cards. I also sent inquiries to some international banks, but as of presstime, they have not replied. On the receiving end of takedown requests, I queried providers about their methods and motives.

Background for the investigation

To give you some background on why we are involved in take-downs: Even though we protect our customers by adding malicious domains and IPs to our block lists, we also report those sites and try to get them taken offline. This does not always result in a successful takedown, but if there is a chance to protect everyone against malicious sites (and not just our clients), we will always grab the opportunity.

Let’s look at this problem from a few angles, starting with the initiators of takedowns.

Protecting your brand and your customers

Imposters can give your company an undeserved bad reputation and cause financial damages. Many financial companies are held responsible for losses due to phishing mails and fake copies of their websites. So they are generally well organized when it comes to dealing with abuse complaints. In the financial sector, one of the biggest problems is phishing mails linking to imitation sites. These imitations can be convincing, complete with green padlocks and ironic warnings about phishing.

Financial corporations in general and banks in particular are well prepared for abuse cases. Most of them have the following in place:

- Educational pages on their site about how to recognize and deal with phishing attempts.

- Help yourself instructions about what to do if you clicked on a link or entered your credentials on a fake site.

- An abuse email address where customers and researchers can forward phishing mails and where you can report fake sites.

- An abuse department that is constantly fighting to get sites taken offline that are targeting their brand(s).

The spokesperson for ICS let us know that they always attempt to take down malicious sites and are successful in about 300 cases per month, globally. In their experience, most providers are quick to take action, but sometimes differing time zones and office hours drag on the process longer than necessary.

At Malwarebytes, we also have to deal with imposters, some of which are selling our free product and others who are tech support scammers pretending to be our support department. William Tsing has had a few of these guys for breakfast, but there are some cases where it is frustrating to have fraudulent content removed. Some of our grievances are:

- Dealing with automated bots that are impossible to convince there is something fraudulent going on.

- No response from the provider at all.

- A culture that would rather receives complaint about the content than from disgruntled customers who had their content removed—no matter what that content is.

This provider apparently knows what should be removed.

Hosting and other providers

As mentioned earlier, we also sent some inquiries to hosting companies and, this may not come as a surprise: the companies that actually do act upon takedown requests were the only ones that responded. The rest decided to deal with my request for information in the same way they would with a takedown request—they ignored it.

According to Steven Burn, who is responsible for the Malwarebytes block lists, this is typical behavior. In his experience, however, Western European and North American hosting companies are usually a lot more cooperative than Russian and Chinese providers.

We have asked these hosting companies what they consider malicious content, and the ones that responded agreed on the following reasons for taking sites offline:

- Phishing content

- Hacking content

- Malware (as downloads)

- Spamming

Some others also specified:

- Illegal software and cracks

- Inappropriate content

These providers all estimated the time between receiving a complaint and fixing the problem to be well under eight working hours. I know from experience that most are even faster. We also know that the ones that didn’t respond are more likely to deal with requests from big companies faster than those of researchers, or as they put it,” unrelated third parties.” And some may not respond at all, or worse, have an automated bot send you responses that drive you up the wall or into despair.

URL-shorteners

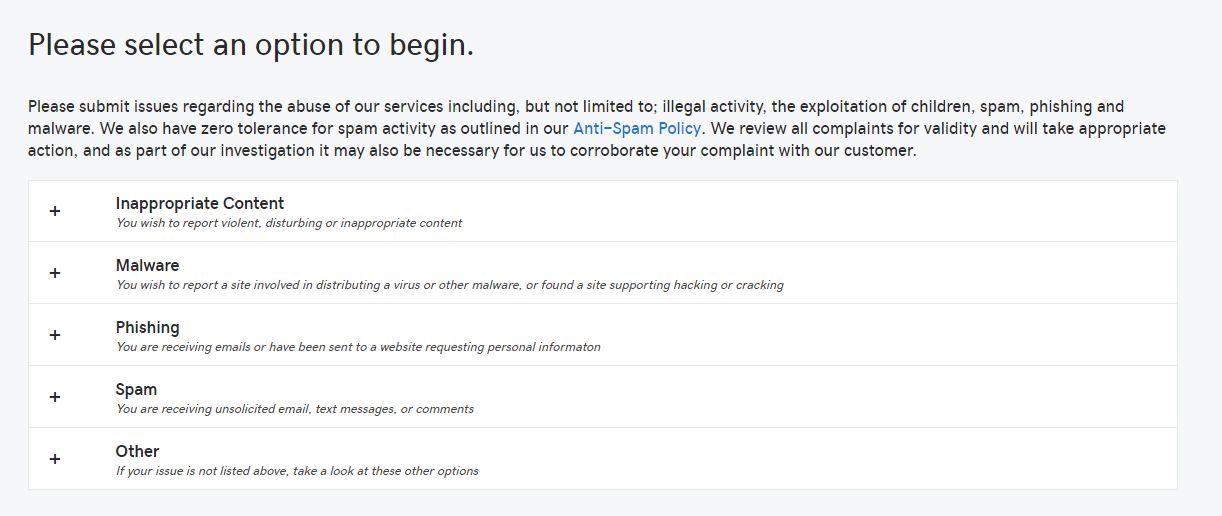

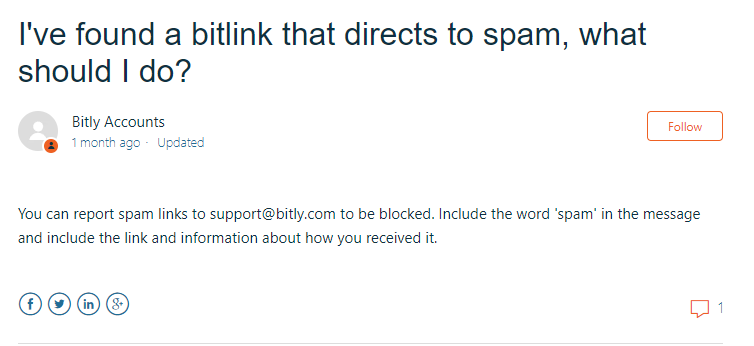

There are other providers at play when it comes to malicious sites. Take, for example, URL-shorteners. URL shortening services are often used by cybercriminals to obfuscate redirects to malicious destinations. So, if you’re unable to get the website itself removed because the hosting provider is unresponsive, you can try to get the URL-shortener to remove the shortened link from their redirections list. In some cases where the threat actor spread the link only in the shortened form, this could be just as effective. Most of these URL-shortening services provide excellent support, as well as detailed instructions on their site on how to proceed.

Registrars

A domain name registrar is a company that manages the reservation of Internet domain names. In the chain of hosting malicious websites, they are at least as important as the company providing the physical server. A registrar can stop DNS requests for a domain to end up at the correct server. A registrar is also the player that has to enable threat actors when they use techniques like Domain Generating Algorithms (DGA). If the threat actor is unable to automatically register the domains generated by the algorithm, the entire setup of the DGA fails. Sometimes the registrar and the hosting company are the same, but this is not always the case.

Server scans

Another question I asked the providers is whether they perform scans of their servers for inactive malware or for malicious sites. Inactive malware on a server could indicate that a website is hosting malware for download. Hosted malware can be used as a payload for downloader Trojans, or it could be offered for download under the smokescreen of pretending to be a legitimate file. The providers responded that their servers are protected, but not by security software that scans for inactive malware. One provider, however, indicated that they scan newly-created sites for signs that the site could be used for malicious purposes in order to proactively set them offline.

Security researchers

Many security researchers will report their findings to interested parties. How effective they are seems to depend on how well they are connected. This is unfortunate, as requests from relatively unknown researchers can be just as legitimate as those from longtime players. Our belief is that every complaint should be taken seriously, whether it was sent to the general abuse email address or to the head of the department; whether it comes from a finance company, an antivirus vendor, or an independent botnet researcher.

Our experience with providers varies so widely that it’s hard to give general guidance. There is a provider that lets Steven Burn take sites offline himself and asks questions later. There was a provider that kept getting abused by tech support scammers, but when I pointed it out to them, they sought and found a common property in all the accounts that the threat actors registered with them. By doing so, they were able to root out all the scammers’ sites, even the ones that hadn’t been published yet. These are some examples of the ways in which we could work together to make the Internet a safer place.

But if you are a researcher or work in an abuse department, you also know the other end of the spectrum. I’m talking about the providers that would sell their grandfather for a buck or the social media giants that get so many complaints, it takes months just to get past the automated responses.

The answer to my question

In an ideal world, threat actors would have to use their own servers to host malicious sites. This would make it a lot easier for law enforcement to find out who they are and put them where they belong. Talking to some of the people that have to deal with this problem on a daily basis has more or less confirmed what I already suspected: the underlying problem for the hosting of malicious sites is about money. However, it’s perhaps a bit more nuanced than I originally believed. My revision to my original answer, then would be that two issues are at play:

- The provider does not care where the money comes from, or how the site will be used to make more money.

- The provider has not prioritized spending money on a functioning abuse department.

Is there anything we can do to change these attitudes? There is one way to get providers to sit up and listen. When we host our own sites, we can ask ourselves which type of provider we would rather do business with: one that takes abuse seriously, or one that turns a blind eye to cybercrime? If negligent practices turn into profit losses, it’s likely these hosting companies will take takedown requests more seriously.

Waiting for legislation that holds providers partly responsible for the content they are hosting could take a long time—or it may not even happen in some countries. It’s best, then, to take matters into your own hands. If you see something, say something. And if you own your own website now or plan to launch one in the future, look into the business practices of those hosting companies and invest in those that are taking Internet safety seriously.

Do you have takedown experiences of your own to share? Have you ever reported a malicious site to a provider? Sound off in the comments section.