While families gathered for food and merriment on Christmas Eve, most businesses slumbered. Nothing was stirring, not even a mouse—or so they thought.

For those at Tribune Publishing and Data Resolution, however, a silent attack was slowly spreading through their networks, encrypting data and halting operations. And this attack was from a fairly new ransomware family called Ryuk.

Ryuk, which made its debut in August 2018, is different from many other ransomware families we’ve analyzed, not because of its capabilities, but because of the novel way it infects systems.

So let’s take a look at this elusive new threat. What is Ryuk? What makes it different from other ransomware attacks? And how can businesses stop it and similar threats in the future?

What is Ryuk?

Ryuk first appeared in August 2018, and while not incredibly active across the globe, at least three organizations were hit with Ryuk infections over the course of the first two months of its operations, landing the attackers about $640,000 in ransom for their efforts.

Despite a successful infection run, Ryuk itself possesses functionality that you would see in a few other modern ransomware families. This includes the ability to identify and encrypt network drives and resources, as well as delete shadow copies on the endpoint. By doing this, the attackers could disable the Windows System Restore option for users, and therefore make it impossible to recover from the attack without external backups.

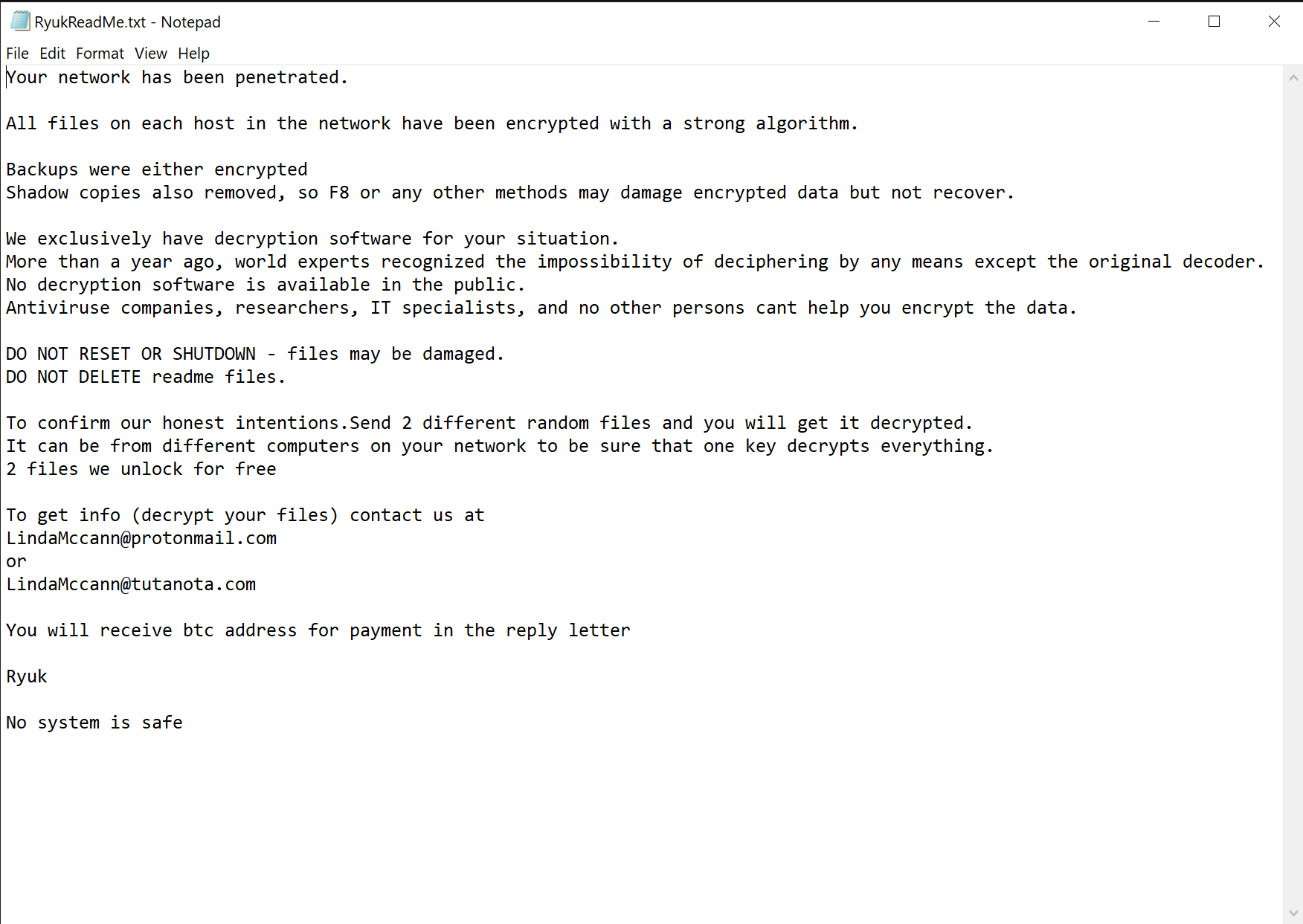

Ryuk “polite” ransom note

One interesting aspect of this ransomware is that it drops more than one note on the system. The second note is written in a polite tone, similar to notes dropped by BitPaymer ransomware, which adds to the mystery.

Ryuk “not-so-polite” ransom note

Similarities with Hermes

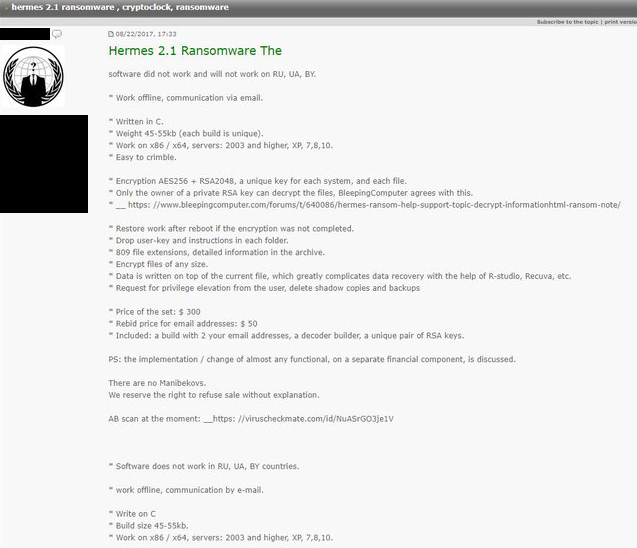

Researchers at Checkpoint have already conducted deep analysis of this threat, and one of their findings was that Ryuk shares many similarities with another ransomware family: Hermes.

Inside of both Ryuk and Hermes, there are numerous instances of similar or identical code segments. In addition, several strings within Ryuk have been discovered that refer to Hermes—in two separate cases.

When launched, Ryuk will first look for the Hermes marker that is inserted into each encrypted file. This is a means to identify if the file or system has already been attacked and/or encrypted.

The other case involves whitelisted folders, and while not as damning as the first, the fact that both ransomware families whitelist certain folder names is another clue that the two families might share originators. For example, both Ryuk and Hermes whitelist a folder named “Ahnlab”, which is the name of a popular South Korean security software.

If you know your malware, you might remember that Hermes was attributed to the Lazarus group, who are associated with suspected North Korean nation-state operations. This has led many analysts and journalists to speculate that North Korea was behind this attack.

We’re not so sure about that.

Notable attacks

Multiple notable Ryuk attacks have occurred over the last few months primarily in the United States, in which the ransomware infected large numbers of endpoints and demanded higher ransoms than what we typically see (15 to 50 Bitcoins).

One such attack was on the Onslow Water and Sewer Authority (OWASA) on October 15, 2018, which kept the organization from being able to use their computers for a time. While water and sewage services, as well as customer data, were untouched by the ransomware attack, it still caused significant damage to the organization’s network and resulted in numerous databases and systems being rebuilt from the ground up.

Infection method

According to Checkpoint and multiple other analysts and researchers, Ryuk is spread as a secondary payload through botnets, such as TrickBot and Emotet.

Here is the running theory: Emotet makes the initial infection on the endpoint. It has its own abilities to spread laterally throughout the network, as well as launch its own malspam campaign from the infected endpoint, sending additional malware to other users on the same or different networks.

From there, the most common payload that we have seen Emotet drop over the last six months has been TrickBot. This malware has the capability to steal credentials, and also to move around the network laterally and spread in other ways.

Both TrickBot and Emotet have been used as information stealers, downloaders, and even worms based on their most recent functionality.

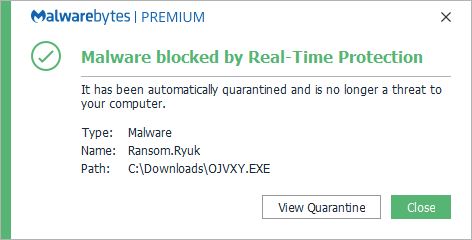

At some point, for reasons we will explore later in this post, TrickBot will download and drop Ryuk ransomware on the system, assuming that the infected network is something that the attackers want to ransom. Since we don’t see even a fraction of the number of Ryuk detections as we see of Emotet and TrickBot through our product telemetry, we can assume that it’s not the default standard operation to infect systems with Ryuk after a time, but rather something that is triggered by a human attacker behind the scenes.

Stats

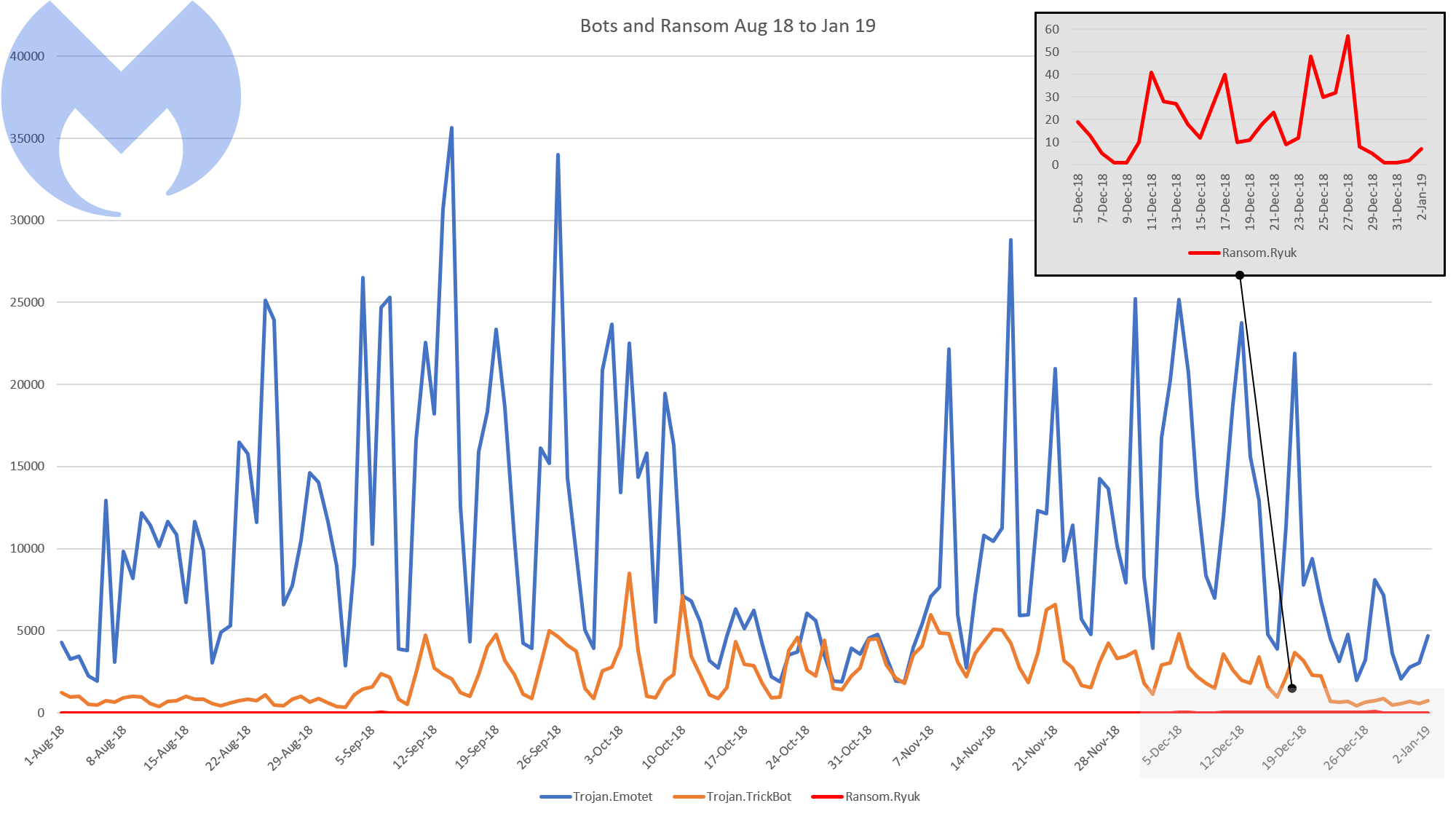

Let’s take a look at the stats for Emotet, Ryuk, and TrickBot from August until present-day and see if we can’t identify a trend.

Malwarebytes’ detections from August 1, 2018 – January 2, 2019

The blue line represents Emotet, 2018’s biggest information-stealing Trojan. While this chart only shows us August onward, rest assured that for much of the year, Emotet was on the map. However, as we sailed into Q4 2018, it became a much bigger problem.

The orange line represents TrickBot. These detections are expected to be lower than Emotet, since Emotet is usually the primary payload. This means that in order for TrickBot to be detected, it must have either been delivered directly to an endpoint or dropped by an Emotet infection that was undetected by security software or deployed on a system without it. In addition, TrickBot hasn’t been the default payload for Emotet for the entire year, as the Trojan has continuously swapped payloads, depending on time of year and opportunity.

Based on this, to get hit with Ryuk (at least until we figure out the real intention here) you would need to have either disabled, not installed, or not updated your security software. You would need to refrain from conducting regular scans to identify TrickBot or Emotet. You would need to either have unpatched endpoints or weak credentials for TrickBot and Emotet to move laterally throughout the network and then, finally, you would need to be a target.

That being said, while our detections of Ryuk are small compared to the other families on this chart, that’s likely because we caught the infection during an earlier stage of the attack, and the circumstances for a Ryuk attack need to be just right—like Goldilocks’ porridge. Surprisingly enough, organizations have created the perfect environment for these threats to thrive. This may also be the reason behind the huge ransom payment, as fewer infections lead to fewer payouts.

Christmas campaign

While active earlier in the year, Ryuk didn’t make as many headlines as when it launched its “holiday campaign,” or rather the two largest sets of Ryuk infections, which happened around Christmastime.

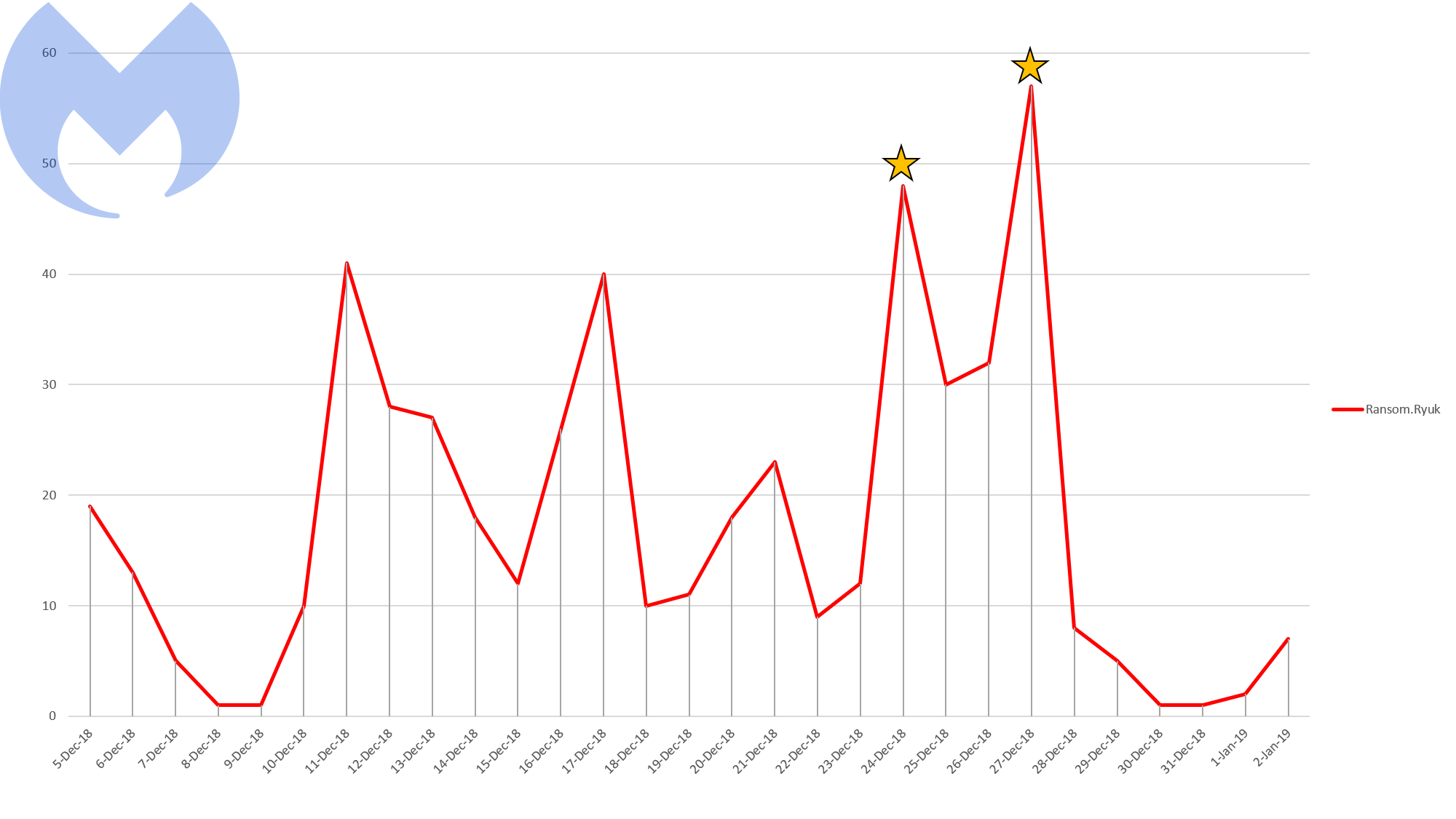

The chart below shows our detection stats for Ryuk from the beginning of December until now, with the two infection spikes noted with stars.

Malwarebytes’ Ryuk detections December 5, 2018 – January 2, 2019

These spikes show that significant attacks occurred on December 24 and December 27.

Data Resolution attack

The first attack was on Dataresolution.net, a Cloud hosting provider, on Christmas Eve. As you can see from above, it was the most Ryuk we had detected in a single day over the last month.

According to Data Resolution, Ryuk was able to infect systems by using a compromised login account. From there, the malware gave control of the organization’s data center domain to the attackers until the whole network was shut down by Data Resolution.

The company assures customers that no user data was compromised, and the intent of the attack was to hijack, not steal. Although, knowing how this malware finds its way onto an endpoint in the first place is a good sign that they’ve probably lost at least some information.

Tribune Publishing attack

Our second star represents the December 27 attack, when multiple newsprint organizations under the Tribute Publishing umbrella (now or in the recent past) were hit with Ryuk ransomware, essentially disabling these organizations’ ability to print their own papers.

The attack was discovered late Thursday night, when one of the editors at the San Diego Union-Tribune was unable to send finished pages to the printing press. These issues have since been resolved.

Theories

We believe Ryuk is infecting systems using Emotet and TrickBot to distribute the ransomware. However, what’s unclear is why criminals would use this ransomware after an already-successful infection.

In this case, we can actually take a page from the Hermes playbook. We witnessed Hermes being used in Taiwan as a means to cover the tracks of another malware family already on the network. Is Ryuk being used in the same way?

Since Emotet and TrickBot are not state-sponsored malware, and they are usually automatically launched to a blanket of would-be victims (rather than identifying a target and being launched manually), it seems odd that Ryuk would be used in only a few cases to hide the infection. So perhaps we can rule this theory out.

A second, more probable theory is that the purpose of Ryuk is as a last ditch effort to extort more value from an already-juicy target.

Let’s say that the attackers behind Emotet and TrickBot have their bots map out networks to to identify a target organization. If the target has a large enough infection spread of Emotet/TrickBot, and/or if its operations are critical or valuable enough that disruption would trigger an inclination to pay the ransom, then that might make them the perfect target for a Ryuk infection.

The true intention for using this malware can only be speculated at this point. However, whether it’s hiding the tracks of other malware or simply looking for ways to make more cash after stealing all the relevant data they could, businesses should be wary of writing this one off.

The fact remains that there are thousands of active Emotet and TrickBot infections all over the world right now. Any of the organizations that are dealing with these threats need to take them seriously, because an information stealer might turn into nasty ransomware at any time. This is the truth of our modern threat landscape.

Attribution

As mentioned earlier, many analysts and journalists have decided that North Korea is the most likely attacker to be distributing Ryuk. While we can’t completely rule this out, we aren’t entirely sure it’s accurate.

Ryuk does match Hermes in many ways. Based on the strings found, it was likely built on top of, or is a modified version of Hermes. How the attackers got the source code is unknown, however, we have observed instances where criminals were selling versions of Hermes on hacker forums.

This introduces another potential reason the source code got into the hands of a different actor.

Identifying the attribution of this attack based on similarities between two families, one of which is associated with a known nation-state attack group (Lazarus) is a logical fallacy, as described by Robert M. Lee in a recent article, “Attribution is not Transitive – Tribute Publishing Cyber Attack as a Case Study.” The article takes a deeper dive into the errors of attribution based on flimsy evidence. We caution readers, journalists, and other analysts on drawing conclusions from correlations.

Protection

Now that we know how and potentially why Ryuk attacks businesses, how can we protect against this malware and others like it?

Let’s focus on specific technologies and operations that are proven effective against this threat.

Anti-exploit technology

The use of exploits for both infection and lateral movement has been increasing for years. The primary method of infection for Emotet at the moment is through spam with attached Office documents loaded with malicious scripts.

These malicious scripts are macros that, once the user clicks on “Enable content” (usually through some kind of social engineering trick), will launch additional scripts to cause havoc. We most commonly see scripts for JavaScript and PowerShell, with PowerShell quickly becoming the de-facto scripting language for infecting users.

While you can stop these threats by training users to recognize social engineering attempts or use an email protection platform that recognizes malicious spam, using anti-exploit technology can also block those malicious scripts from trying to install malware on the system.

In addition, using protection technologies, such as anti-ransomware add immense amounts of protection against ransomware infections, stopping them before they can do serious damage.

Regular, updated malware scans

This is a general rule that has been ignored enough times to be worth mentioning here. In order to have effective security solutions, they need to be used and updated frequently so they can recognize and block the latest threats.

In one case, the IT team of an organization didn’t even know they were lousy with Emotet infections until they had updated their security software. They had false confidence in a security solution that wasn’t fully armed with the tools to stop the threats. And because of that, they had a serious problem on their hands.

Network segmentation

This is a tactic that we have been recommending for years, especially when it comes to protecting against ransomware. To ensure that you don’t lose your mapped or networked drives and resources if a single endpoint gets infected, it’s a good idea to segment access to certain servers and files.

There are two ways to segment your network and reduce the damage from a ransomware attack. First, restrict access to certain mapped drives based on role requirements. Second, use a separate or third-party system for storing shared files and folders, such as Box or Dropbox.

Evolving threats

This last year has brought with it some novel approaches to causing disruption and devastation in the workplace. While ransomware was the deadliest malware for businesses in 2017, 2018 and beyond look to bring us multiple malware deployed in a single attack chain.

What’s more, families like Emotet and TrickBot continue to evolve their tactics, techniques, and capabilities, making them more dangerous with each new generation. While today, we might be worried about Emotet dropping Ryuk, tomorrow Emotet could simply act as ransomware itself. It’s up to businesses and security professionals to stay on top of emerging threats, however minor they may appear, as they often signal a change in the shape of things to come.

Thanks for reading and safe surfing!