Chances are you’ve probably used Adobe Reader before to read Portable Document Format (PDF) files. Adobe Reader—formerly Acrobat Reader—remains the number one program used to handle PDF files, despite competition from others.

However, Adobe Reader has a history of vulnerabilities and gets exploited quite a bit. Once exploitation succeeds, a malware payload can infect a PC using elevated privileges.

For these reasons, it’s good to know how to analyze PDF files, but analysts first need a basic understanding of a PDF before they deem it malicious: here is the information you’ll need to know.

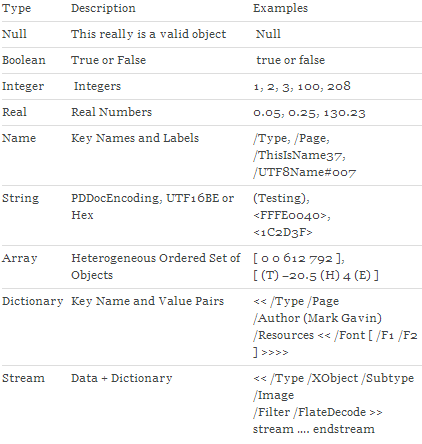

A PDF file is essentially just a header, some objects in-between, and then a trailer. Some PDF files don’t have a header or trailer, but that is rare. The objects can either be direct or indirect, and there are eight different types of objects.

Direct objects are inline values in the PDF (/FlatDecode, /Length, etc) while indirect objects have a unique ID and generation number (obj 20 0, obj 7 0, etc). Indirect objects are usually what we’re paying attention to when analyzing PDF malware, and can be referenced by other objects in a PDF file.

Knowing that, let’s look at some PDF malware. We’re going to observe a PDF that exploits CVE-2010-0188, a very common exploit found in the wild. For reference purposes, the md5 hash of our target file is 9ba98b495d186a4452108446c7faa1ac.

The first thing we need is analysis tools.

I find the PDF tools by Didier Stevens to be some of the best out there. Stevens’ tools are all written in Python and are very well documented. For this particular malware, we’ll be using Stevens’ tools along with some other tools used to de-obfuscate and debug code.

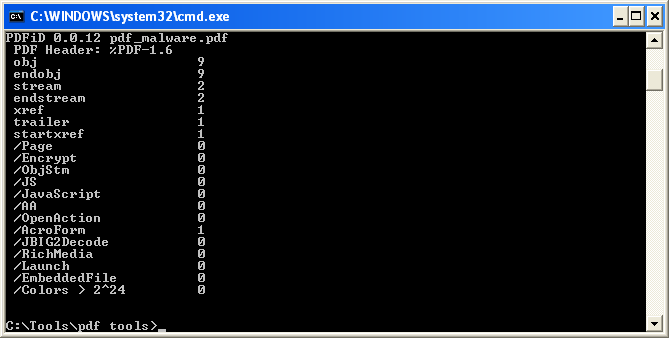

PDFiD is the first tool we will use, and is a very simple script that searches for suspicious keywords. Here is the output from the scan of our target file.

The output from PDFiD reports there are nine objects. From those objects there are two streams, along with an AcroForm object. Let’s observe the AcroForm object first. For this, we’re going to use a different tool by Stevens called pdf-parser, which will take a closer look at specific PDF objects.

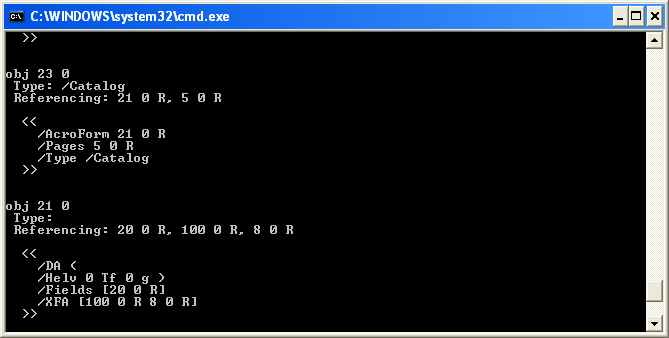

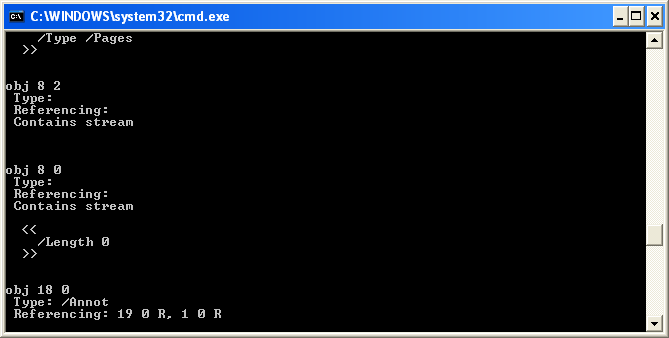

The AcroForm object references object 21 below. From object 21, we see the text “XFA”, which stands for XML Forms Architecture, an Adobe format used for PDF forms. Next to XFA we see two objects referenced: obj 100 and 8. Since there is no obj 100, we’ll take a look at obj 8 instead.

There are two objects available with different generation numbers: obj 8 0 and the other 8 2. The generation number simply represents the version number of the object and increments whenever there are multiple instances of one object ID. However, obj 21 references obj 8 0, so let’s stay focused on the first one.

Here is where things start to get interesting. Inside 8 0 we see there is a stream that appears to be zero-length (/Length 0). Streams are basically large sets of data. With a malicious PDF, that usually means JavaScript exploit code is inside, which will likely lead to the execution of shellcode.

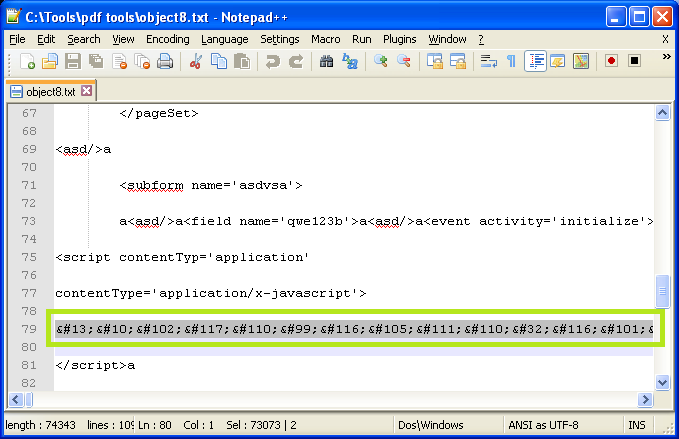

Now that we have our eyes on 8 0, we should investigate it further using pdf-parser. We’re going to look specifically at the raw output of 8 0 using the following command (the output was quite long, so I sent it to a text file):

python pdf-parser.py -f -o 8 -w pdf_malware.pdf > object8.txtAnd now we’ll look at the output, which appears to contain some JavaScript. Inside the script you’ll see a very long sequence of characters. It would seem the length of the data stream is not 0 as originally led to believe.

These values are numeric character references (NCRs). In HTML, character references to  are not allowed, except for 9, 10, and 13. These are control characters that do not represent a printable value.

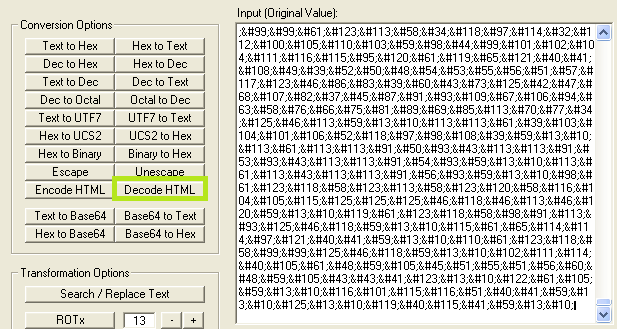

In order for us to understand what these character references represent, we need to consult the ASCII table. However, due to the sheer amount of character references we have, it would take some time to convert these manually. We will either need a script or some special tool to perform rapid conversions. Thanks to Kahu Security, we have such a tool called the Converter.

Converter is a simple program used to take data and convert to/from many types, and also permits bitwise operations. For this PDF malware we can copy the NCRs into Converter and select ‘Decode HTML’.

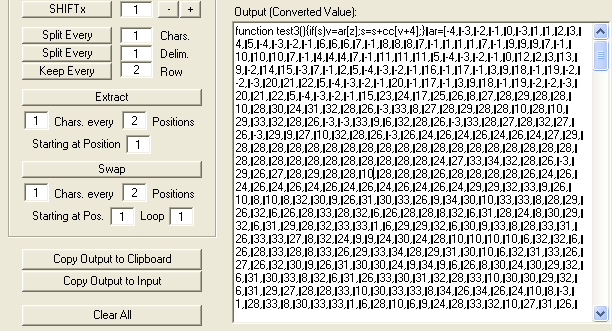

Success! The output box reveals decoded JavaScript.

Now we can paste this JavaScript into a new text file and clean it up. However, there seems to be a problem once we paste the code.

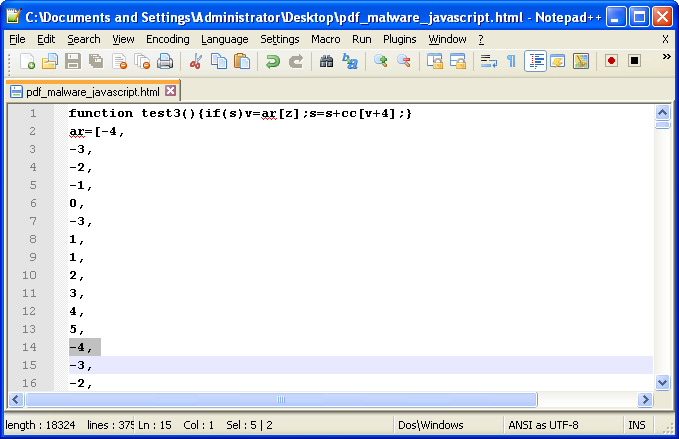

It looks like every value in the “ar” array is printed on a separate line. With almost 4,000 lines in the new document, this would take too long to fix by hand.

The reason for this is that NCR 10 represents a line feed (LF), and is placed after every comma in the array. If you looked at the image of the decoded output, it actually shows up as a little black bar, almost resembling a pipe or sheffer stroke character (“|”).

In order to fix this we only need to do a Find/Replace and remove all occurrences of NCR 10. Afterward, we just repeat the conversion process using Converter, and place the decoded output into a new text file, this time wrapped in