The exploit kit landscape is constantly changing and forcing security researchers to up their game.

There was a time when payloads were not even encrypted and web servers actually not lying.

Unique patterns, packets that match the size of binaries on disk, all make things easier for the good guys to detect and block malicious activity. But the reality is this was just an adaptive phase when the bad guys did not need to spend any extra effort and still got what they wanted: high numbers of infections.

When an exploit kit landing page becomes something like domain.com/index.php you know have a problem. No regular expression on earth is going to be able to avoid the millions of false positives you might hit if you even attempt to do URL pattern matching. And then you have clever obfuscated code that is spread across multiple web requests in separate JavaScripts, very much like… the majority of websites.

Let’s talk about the payload itself. Whether it is in the clear through the wire, or encoded, or sometimes even split, we can still grab it from the disk and pass it on to researchers.

Well, all good things come to an end as they say because now we’re seeing payloads that are fileless (memory-only).

This will be a two-part blog series that will explain how this type of infections works. In the video below, we replicated the ‘classic’ (file-based) attacks versus the memory-only ones. You will also see how traditional security solutions, and in particular whitelisting, are ineffective against this threat.

Classic vs Advanced

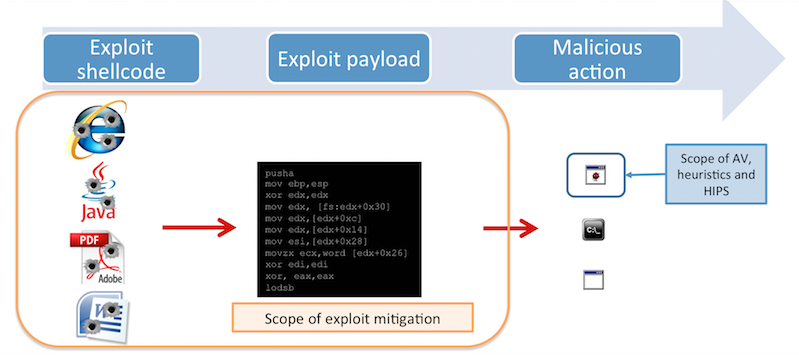

The payload is injected directly into the process used for the exploitation (in our case iexplore.exe) as a new thread (instead of being a file dropped on disk):

There are many advantages of doing that. For starters, by never dropping anything onto the hard-drive, you reduce your payload’s footprint on a system and chances for it to get detected.

It is typically much easier to detect a piece of malware on disk than one hiding in memory. There is at least one exception in case the piece of malware is a rootkit, at which point, the file is technically on disk, but not visible.

From a pure logistical point of view, it is also harder to collect memory-only samples than simply scraping those on disk. This is especially true when the malware is sent as an encoded stream because it becomes much more complex to decode it from a packet capture.

However, being memory-only does have some drawbacks. The attacker has a smaller window of opportunity to carry on his task before the application or system is shutdown.

The most simple way to get rid of these types of threats is to restart your computer which arguably is problematic. But if we look closer, this problem can me mitigated: As we will see in the second part of this analysis, the attackers are hooking into an API that guarantees that the process survives when the user closes the application.

As far as system shutdowns go, most people will spend several hours on their computers before powering it down. This is long enough to capture keystrokes or perhaps even download additional malware.

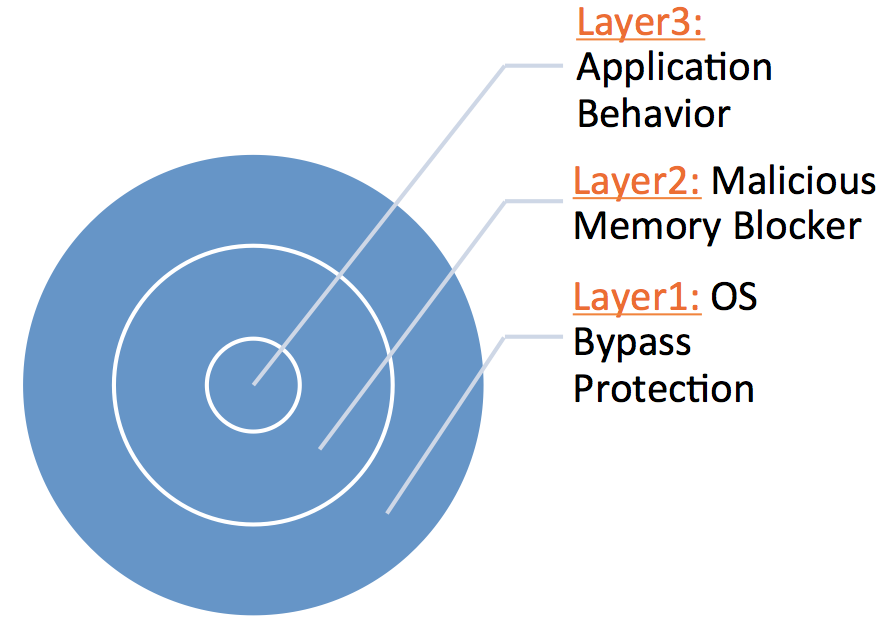

The earlier the better

As with most things, the earlier you can catch something, the better. Traditional security solutions will detect the malicious payload on disk or perhaps in memory, after an exploitation has already happened.

If the piece of malware is new enough, it will get a chance to infect the system. (Note: it is of course possible to detect the attack as early at the URL or IP address level but giving the constant rotation of domain names as well as JavaScript patterns, this is easier said than done.)

To illustrate this better, I will borrow a slide from a recent webinar Pedro Bustamante and I did about exploits:

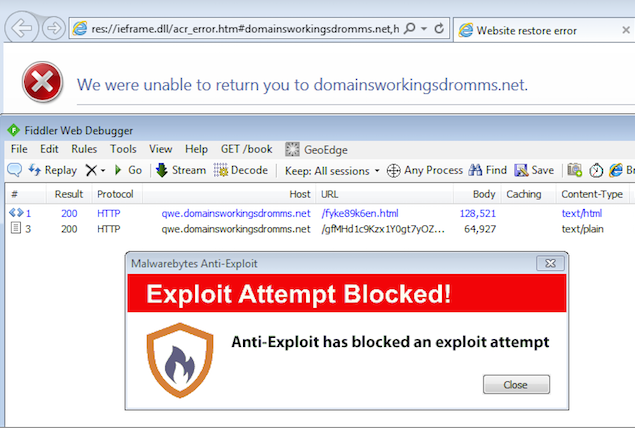

This particular attack was detected and blocked by Malwarebytes Anti-Exploit before the payload had a chance to run. The screenshot below shows two web sessions:

- landing page

- Flash exploit

The Flash exploit was detected and stopped which resulted in a failure to launch the payload (malware):

This is an important aspect because the form of the payload (memory-only or file based) is irrelevant. While other security solutions will often play the cat-and-mouse game to detect malware with signatures, focusing on memory and application behavior gives you the ability to stop a payload while it’s still in the launchpad.

In another twist, Kafeine discovered how the filess EK distributes Poweliks, a threat that is also fileless and uses the registry to achieve persistence:

That was inevitable, this is happening. Filess Poweliks meets Filess Angler EK thread. Combo ! pic.twitter.com/5mobHrlt27

— Kafeine (@kafeine) September 26, 2014

More to come

I studied this case with my colleague David Sánchez, a great security researcher and reverse engineer. If you liked the first part of this mini-series, stay tuned for part 2 where David will walk you through the inner workings of the exploit and payload.

As a teaser, here’s a short video where magic happens (unreadable strings turn into an MZ):

Many thanks to David Sánchez for walking me through the code in a late night Skype session! Additional thanks to joshcannell for helping me with the XOR routine.