We’ve recently wrote about the leak of keys for Chimera ransomware. In this, more technical post, we will describe how to utilize the leaked keys to decrypt files. Also, we will perform some tests in order to validate the leaked material.

Components and approach

Usually, writing a ransomware decryptor requires a deep understanding of the used algorithm and finding some flaws in it’s implementation. Different vulnerabilities require different mindset in creating the cracking tool. Sometimes we need to re-create the vulnerable algorithm and make a tool for guessing keys (like in the case of cracking Petya). Sometimes, the attacked part is a generator of symmetric keys (like in the case of DMA Locker 2.0) – or the algorithm itself (see the custom encryption of 7ev3n ransomware).

But this time we have almost everything ready-made:

- set of the keys (leaked)

- decryptor provided originally by the authors of Chimera to it’s victims (available here)

The interesting part is only in noticing the relationships between the collected pieces and reorganizing them in the desired way.

Reversing the original decryptor

As we described previously in the analysis of Chimera, along with the ransom note, authors provided a link from which the victim could download external tool for decryption. To make it work, user needed to purchase the private key, fitting to the public key with which his files were encrypted.

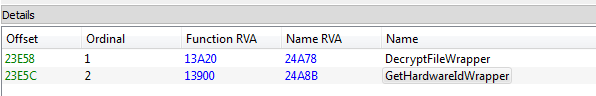

That tool is written in .NET and all the operations of decrypting files are taking place in the external component – a DLL named “PolarisSSLWrapper.dll”, exporting two functions:

So, there is no need to re-implement the decrypting function – we can make a use of the existing API.

Let’s reverse the main (.NET) component first, to see how this function is called and what are the expected arguments.

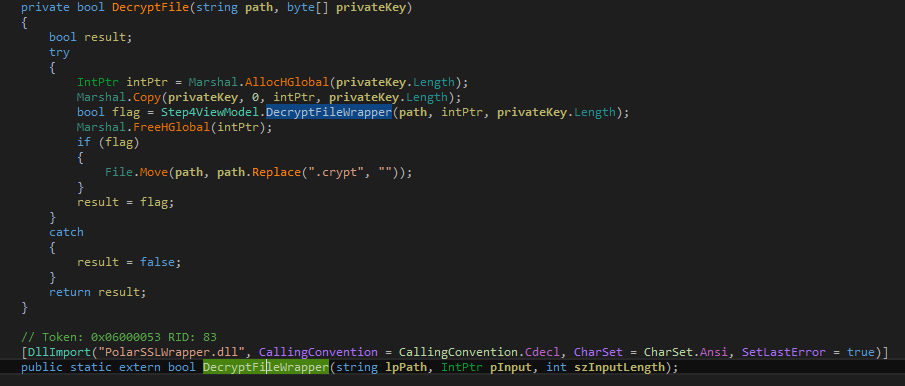

We can see the fragment of code in which the external function is loaded and being called:

As we can see above, the function that we are interested in is DecryptFileWrapper. It takes 3 parameters: path to the encrypted file (in form of an ASCII string, private key (in form of array of bytes) and the private key length. It returns a boolean value, informing if decrypting the file was successful or not. We can reconstruct it’s header as:

bool _cdecl DecryptFileWrapper(char filePath, BYTE* privateKey, size_t privateKeySize);

The private key is read from the received bitmessage, and decoded from Base64 into the array of bytes:

The infrastructure of Chimera is dead from some months, so we cannot see how the traffic looks in real life at the moment. But thanks to the research published at Bleeping Computer we can see what exactly was the structure of the message. Example:

56209A92A96E9F96B0D9E6F962D0D9EF:5Zn9azBBDQQznI9znnHZBDs6+nQz6nB9/6DBa0nXbDz0aghs6fg62Rn9ZzxnDGEzRQ9tFdIZDfa05Lz+nlb6IGnzSDQz0tznrdUzGgq9Nibzx0Zusl2aHn6nzZZE6tbQQe/vzbASDuanTBL5SazSARe52QSq6BEzD5rGqzZhnaLaZrfbI6bN6A6nnnH5lgbeSAzXdz+6eNxqQt9ITziIxF+eDFBBBVZ+zHf6esQzzH2uBnQnaHzzi6tDna9Xngfh6bzQQZBfq+vFbZ9ZfvnTL6D2arAnBzb6A06Qzfn2zRD5hz5eLZzDIDR00/anblbU2bvRTH6ZGaXDeBQQ5NHGhQEAAdZBtx/VaVQsrrDZdasadBHi0RDeZz0Da6glNRz9/U59zXaaeAN0Di5eb2zQtvr5h6Fvb6tzB9THtRUGS6Qzt6BxAz/zTg6gs56h5xXzSnslBQRzngandHzFTaBHix692DLxDaziQnZBQDQRB/Zz5HXQfNzz5aad90+uHAsDBDDVzZsngtbgSHDTzA2X5zQs2tHba5z99qF66IQHqZaZD2erzuDQzzx9NlXaTZEiH2IrVGSZizxEFQzLBl6+BDDn5zuG6x6zBhfaNB56nDUXt6BnzzuvNVq2xzDTn2lSu/QrHzNbFdGSLazTh29z5Fx9D5Zt6QBBrQ+aFuNDhASgDDH20UDnQB00gBa2t6/i+Lq6eV9ZHzzDdEn2T6HXfg+BEnvr5tXB5zZL2zbtvBVxFX2QsBZ9ZrzzG6fIvnvnz6NZ5endiz0IzAQ2Dbqa6gnnsSnznsVIizznibdZIFvF/nsqbVQZB9Zn2nBQUDTQzzDT65NxHzLRvz6VzZsQV5bih+S+shaD6ASaDFzHNQD9ZVIi+ZrafBxes6zqQaBfEs6z+Igd6nZhEzDLZZN/9QbhQzlzfBf5IFL0nqt2qqnSeqgz0bzQgZ9Dq6r50SB6xHhn9DfnNa6hR0DUiubDH5z0+n60UD0Uzz6ti6faD5Sz99f6dtQN6LUfZn/RagfiqnzTXZrvBZv95a9aT9u9tE6qLH0BSNArn0I9rF2eBDQH92zFUBBBVs9e/ZrXZ2Qaz/zn6BzxQ05qtqNQTZ6AS22z6nBf/200L66zasDHrzZ9agHAx2qBNUlRaUDFszInzzaLD5IzGQeQaAU60zz6nZQvVe906uDTXGlaZDDfBQUzD/nRDrZUaa2h59Hf5gbeezTHNiHBaBDzzQBx0BX5Zz92Z2zanfSZZ/2BRnzzzQBzxa/iIxiDNb6Qdd9Bh6/FQnfeznSv5rZ6DZitTGZZUAdzgD5azVAn2G/G+EssFuhV5aBb0N/N2q+2656zgxBBDzn2+0NIZLudxTXRsDNDza0V/9gzzEaqBdZax6QDlfnQhAVIn9XZu/D+gr9+ZRqz5266IBST5E5LBZed/s0zS2QHeBrIHnznZtez+02+Q+50g+ZUD6nrbhR2f+NzB6NgZ6ID9e5hnEEQ99xlnSDZT2aQN6QBRueDRZzNaTz6bvQrGhaBaeFl96hZDZLUDIu6rAzB

It is: [victim ID]:[base64 encoded key] After decoding the key we get 1155 (0x483) bytes long array of bytes. So, that array of raw bytes is the private key with which we have to feed the DLL.

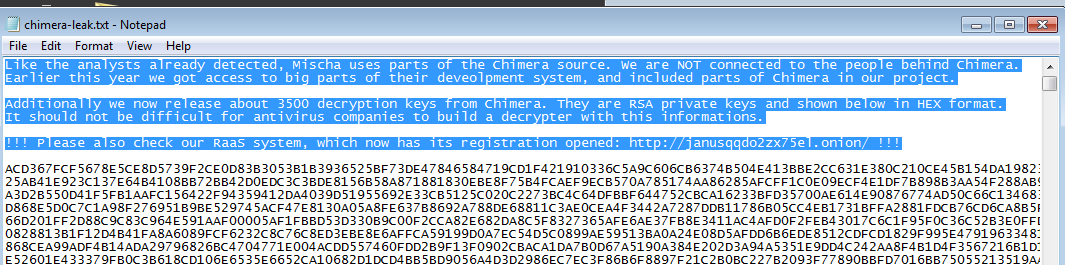

Parsing the keys

The leaked keys are a list of hexadecimal strings. If we convert them to raw, each of them is 0x483 bytes long. It is a good sign, because the format is same as above, and no additional processing is required – only basic parsing from hexadecimal to raw binary.

The file with the leak have a consistent format. Every key ends with a new line. We can just remove the beginning message and use this file as an input:

To be precise: material referred as a set of private keys (in the announcement from the person who leaked them, as well as in the code of original decryptor), in reality is a set of keypairs. Each pair is distributed in a continuous blob that is 0x483 bytes long. First 0x103 bytes contains the public key, and the next 0x380 – the private key. The API of the used DLL expects this full blob to be passed as a ‘private key’ – but thanks to having both of them, it can automatically validate the result of the decryption.

Finding the proper key

As we can see, most of the work is already done. The only remaining thing is to search if in the leaked set there is a key that we needed to decrypt our files.

The algorithm that we must use in this case will looks similar to a dictionary attack. Our “dictionary” is a set of the leaked keys. As a verification we will try to decrypt one of the encrypted files. General idea is described in the pseudocode below:

while ((privateKey = getNextFromSet()) != NULL) { if (DecryptFileWrapper(encryptedFile, privateKey, privateKeyLen) == true) { printf("Hurray, key found!"); storeTheFounKey(privateKey); return true; } } printf ("Sorry, your key is not in the leaked set!"); return false;

Full implementation you can find here.

After finding the matching key, we can decrypt rest of the files with it’s help, using the same DLL.

Testing

Test 1:

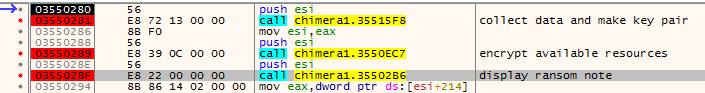

Chimera generates a unique, random keypair at the beginning of each execution. Then, sends it to the C&C via bitmessage (along with other data collected about the victim).

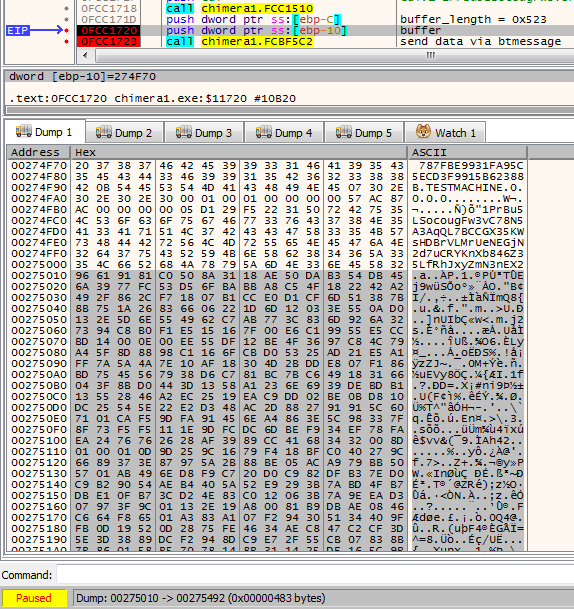

For the test purpose I used a key generated by the original Chimera ransomware sample and dumped it from the memory. The key is visible clearly just before being passed to the function which task is to send the prepared material via bitmessage (you can see it’s beginning selected on the screenshot below):

I converted it to same format as the keys that leaked (continuous hexadecimal string).

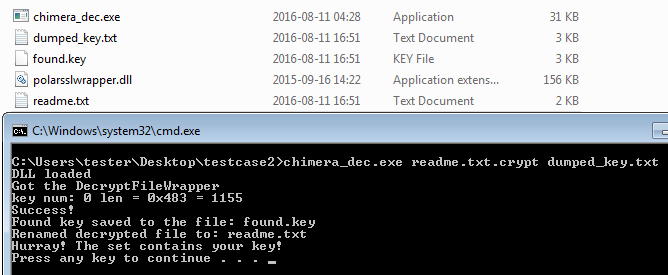

The prepared tool worked – test file has been decrypted successfully:

Test 2:

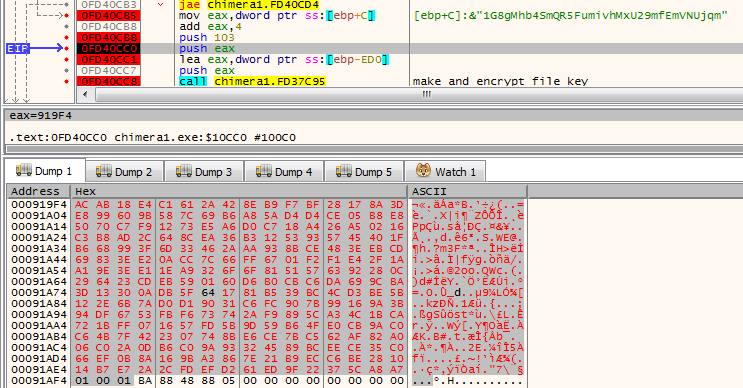

Due to the fact, that in the leaked material we have complete key pairs, we can use them for the testing purpose. In this experiment I cut out the public key from one of the leaked blobs. Then, I supplied it to the original Chimera sample and deployed. This trick allows to generate encrypted sample set imitating files that could belong to a victim who’s key leaked.

Below – substituting the generated public key by the key fetched from the leaked set:

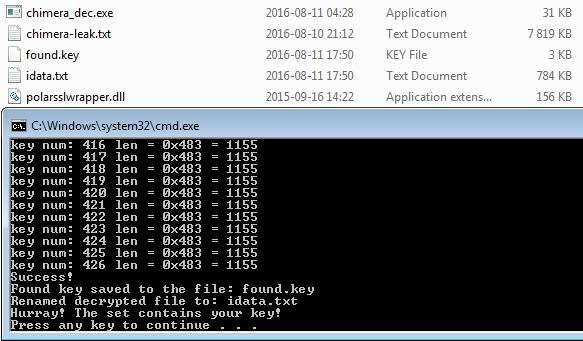

Now, we can attempt to decrypt the attacked file using the set of leaked keys and the prepared application:

And it worked! This test have proven, that the supplied material contains real key pairs, compatible with the format used by Chimera (not just a random set of rubbish data).

Some of the test cases, as well as the compiled application, are available in the github repository.

Conclusion

Looking at the format of keys, we can expect that the leak contains legitimate data. Also, contacting with other researcher (Fabian Wosar) we got confirmation, that some of the keys from the leak are matching the sample of captured traffic. However, we didn’t had an opportunity get evidence from any victim. Chimera is dead from some months, and probably most of the infected people already deleted their encrypted files.

If by any chance you are a victim of Chimera, capable to provide any of such evidence, please contact us.

Appendix

/blog/threat-analysis/2015/12/inside-chimera-ransomware-the-first-doxingware-in-wild/

This was a guest post written by Hasherezade, an independent researcher and programmer with a strong interest in InfoSec. She loves going in details about malware and sharing threat information with the community. Check her out on Twitter @hasherezade and her personal blog: https://hshrzd.wordpress.com.