Ad fraud is one of many issues that contribute to the ad industry’s negative image these days. Unlike malvertising which affects end users by infecting them with malware, ad fraud costs advertisers billions of dollars in adverts that were never seen by real humans.

The case we are describing today shows some interesting tricks to have people click on camouflaged adverts while thinking they are clicking on the play button of a video. The ultimate goal is to generate pay per impression and pay per click revenues from what looks like clean and trusted traffic.

In addition, the crooks are tracking the movements and clicks of the mouse while the user is on the fraudulent page, in order to be able to tell if their victim is an actual person or simply a bot. If the latter is detected, the page will automatically redirect to google.com to prevent any accidental and ‘tainted’ click on the advert.

Apparently the bad guys are concerned about ad fraud too when it matters to them…

Different means, same end goal

There are different ways criminals go about profiting from ad fraud, the most common one being via compromised computers (bots) that view or click on ads unbeknownst to their users. Malware like Bedep can mimic real user activity in hidden desktops and defraud millions of ad impressions a day.

Late last year White Ops, a company that specializes in ad fraud research, exposed a large operation dubbed Methbot involving a different method to generate millions in fraudulent ad revenues. Rather than relying on end user machines, the crooks leveraged data centers to create bot farms. Why bother with unreliable consumer PCs when you can create an army of well-trained ad fraud bots running at optimal speed on server racks?

There are many other ways to game the ad ecosystem and they don’t always involve infecting machines or using bot farms. Sometimes ad fraud can be done in a very transparent manner that relies on a real human to perform an action, making it harder for anti-fraud systems to detect. For instance, clickjacking, a technique that consists of tricking the user to click something that is actually producing a hidden malicious action has been used in the past to do click fraud.

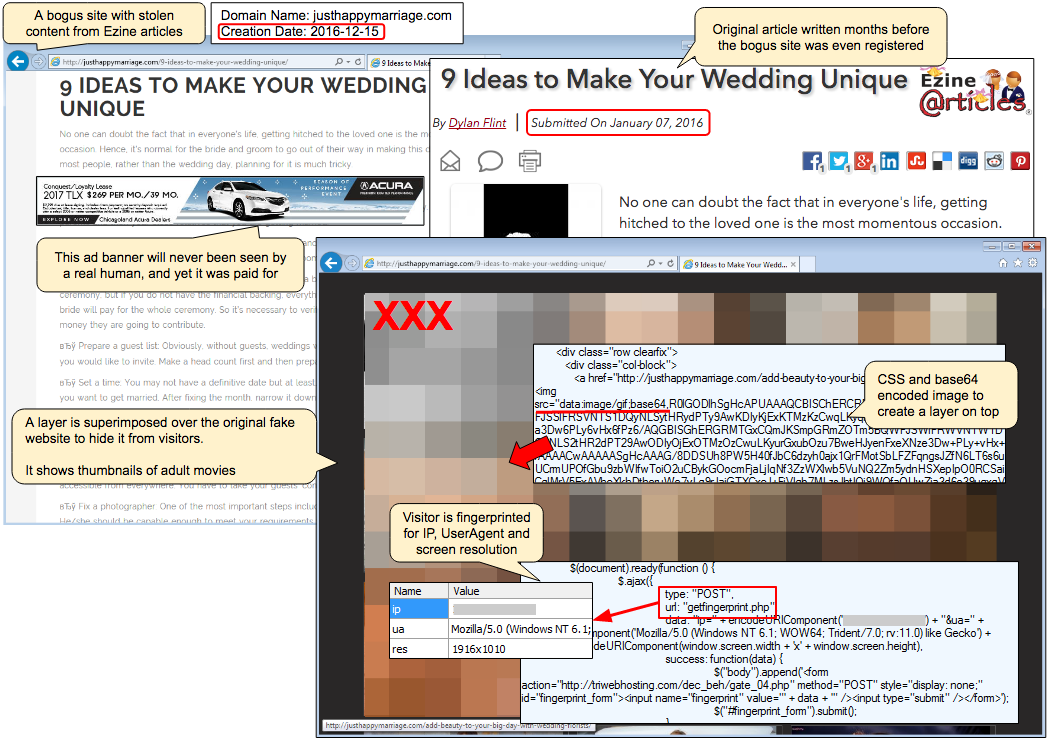

The case we are going to have a look at today is actually related to a clickjacking attack we wrote about before. We discovered this ad fraud campaign via a high profile malvertising chain we have come across already that typically redirects to exploit kits. Visitors to a high traffic adult site are automatically redirected to what appears to be another adult streaming video page. What they don’t know is that it is completely fake and underneath of it are websites displaying paid adverts and generating the crooks money for each impression and click.

Gates

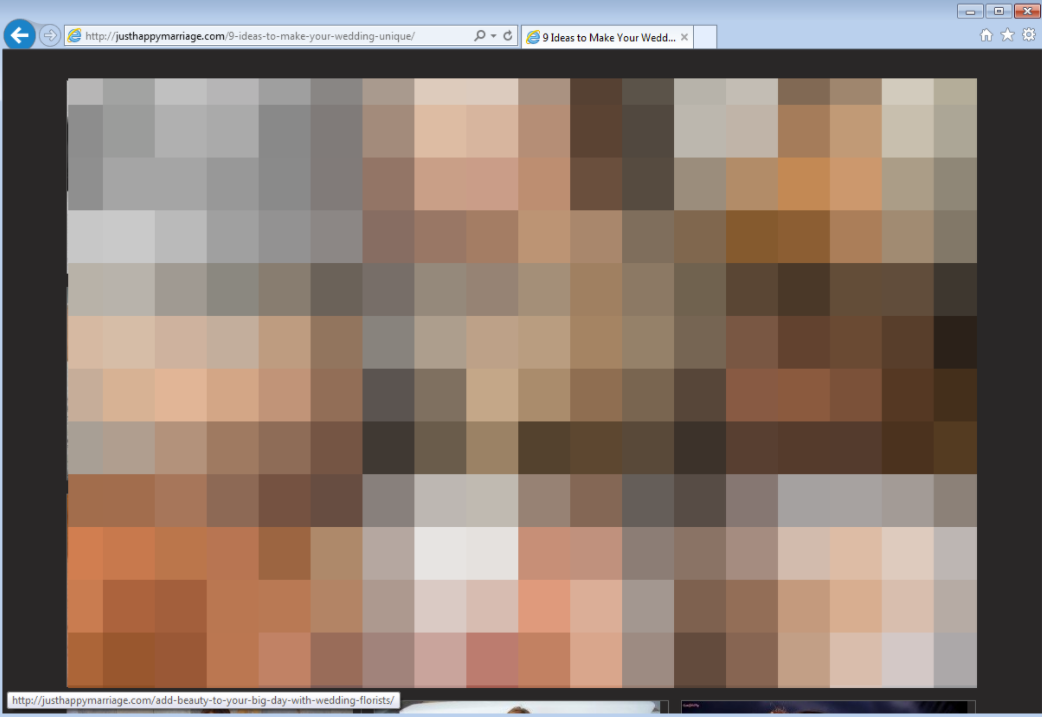

The scenario here is that traffic to some popular adult websites will get redirected via malicious advertising to one of several fake blogs with topics ranging anywhere from wedding tips, pest control, or appliances.

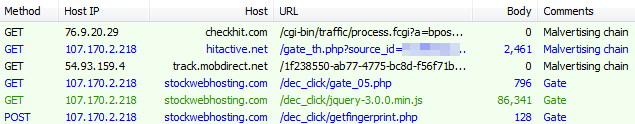

The redirection chain includes the mandatory passage through what we call a gate whose objective is typically to inspect incoming traffic and take actions.

Within one of those gates, we noticed interesting bits of code that was meant to “fingerprinting” visitors to collect their IP address, User-Agent, and screen resolution via a POST request, upon the initial redirection from malvertising.

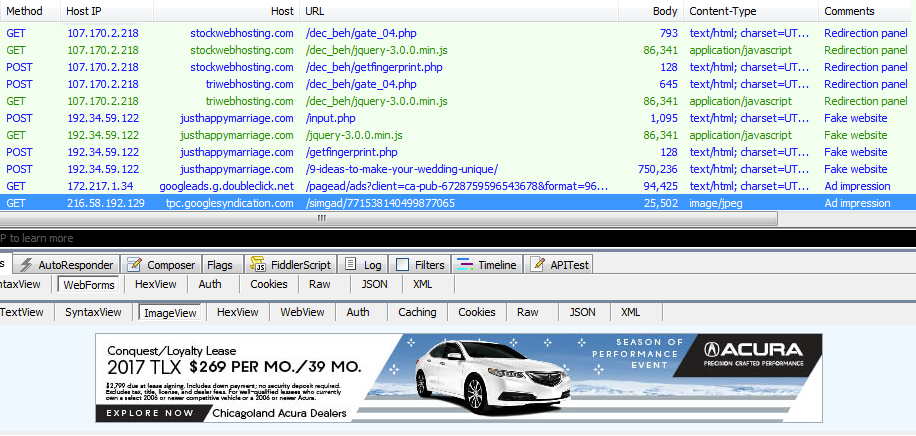

Figure 1: Fingerprinting code at the gate (click to enlarge)

This information is typically harvested by most websites for stats and optimization purposes, but given the explicit use of an appropriately named getfingerprint.php file, we can assume that the fraudsters were trying to identify real users versus crawlers or repeated visits of the same page.

Figure 2: Web traffic from malvertising to gate (click to enlarge)

A façade: adult gallery hides fake blog

Content is one of those things that is very important to search engines and other crawlers as it ultimately gives more value to a website. A long time ago, blackhat SEO criminals used a technique known as keyword stuffing which aimed at getting the site ranked high in the search engine result pages (SERP), but it is easy to detect nowadays.

Plagiarism is still very effective, and copy and paste has never been easier. It’s a cheap way to get some decent content with little effort. In this particular campaign, we witnessed several websites that had been created recently and filled with new blog entries.

It didn’t take long to find out where the write-ups were stolen from: mainly sites like Ezine or Pinterest. The thieves didn’t even bother changing any of the wording, they simply did a copy/paste to populate each of their fraudulent website with dozens of entries.

Figure 3: A fake blog about weddings with stolen content (click to enlarge)

Figure 4: Original content used by fake blog found on Ezine (click to enlarge)

If you visited one of those sites directly, you would see what seems to be a site giving advice for weddings accompanied by a few adverts powered by Google’s DoubleClick, which is quite typical for any website that needs to pay for its operating costs. However, only crawlers most likely visited those websites directly as the motives for setting them up was very clear: to defraud advertisers via hijacked traffic.

A layer containing adult images is superimposed such that both content is displayed in the browser, but only the top layer (adult material) is visible to the eye.

Figure 5: The wedding blog turned into an adult portal thanks to an overlay (click to enlarge)

This is important because the crooks want to load the underlying blog and its content which includes paid adverts so that they can monetize on ad impressions, while at the same time tricking visitors into thinking they are still accessing their adult videos.

Figure 6: Diagram of ad impression fraud via adult page overlay (click to enlarge)

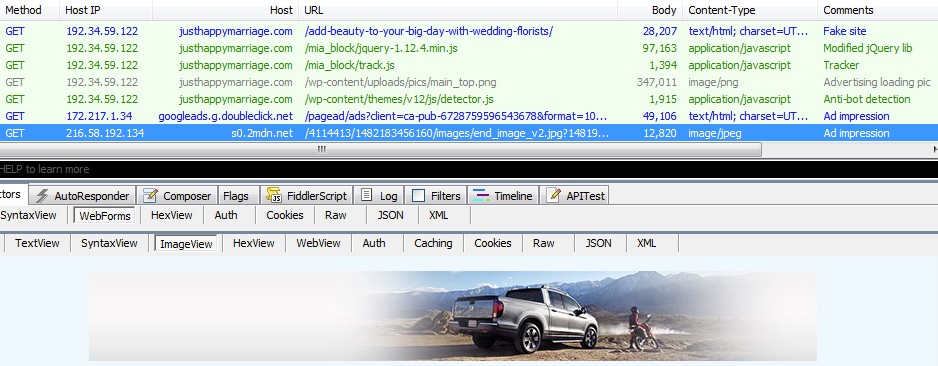

Figure 7: Web traffic from gate to fake blog, to advert (click to enlarge)

Stealing (real) users’ clicks

The first stage of this ad fraud campaign consisted of showing a thumbnail of adult videos while displaying hidden adverts, but that is not all. Users are conned into clicking to actually view any particular video, which takes us to the second part, that involves Pay Per Click (PPC) fraud.

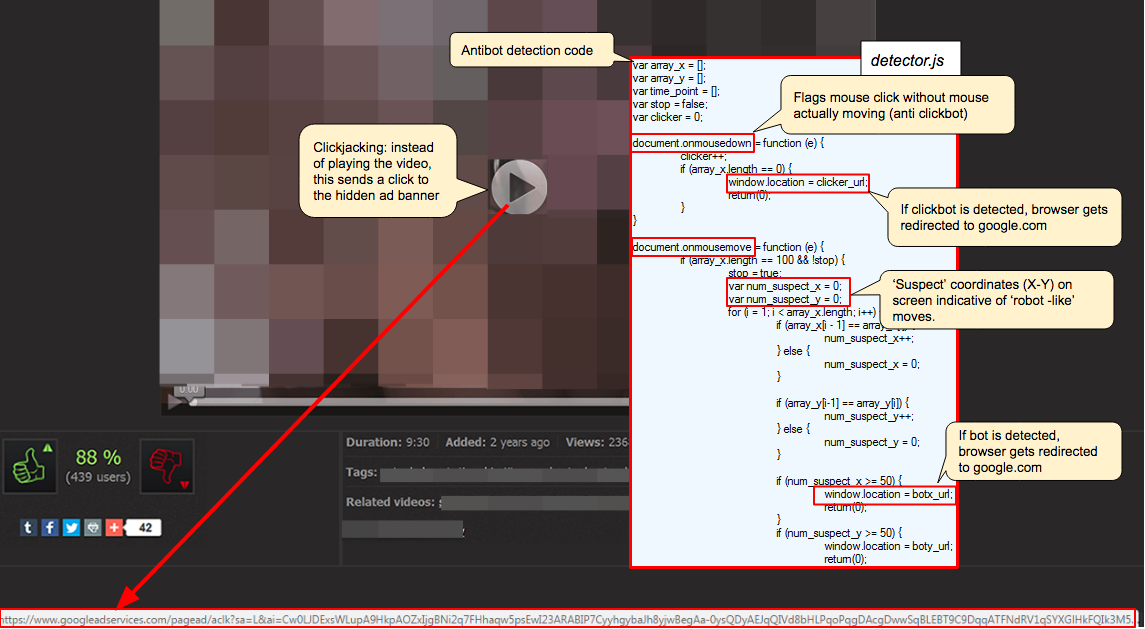

The user is presented with a single adult video page but there is no actual video to be played, as it is just a screenshot designed to mimic a video player with the play button and timeline bar.

The goal is to get users to click on a hidden advert, but only after some validation checks that ensure the clicks are from genuine humans. This is somewhat ironic for fraudsters to check against bots.

Figure 8: Diagram of fake video page which tricks the user into clicking play button (click to enlarge)

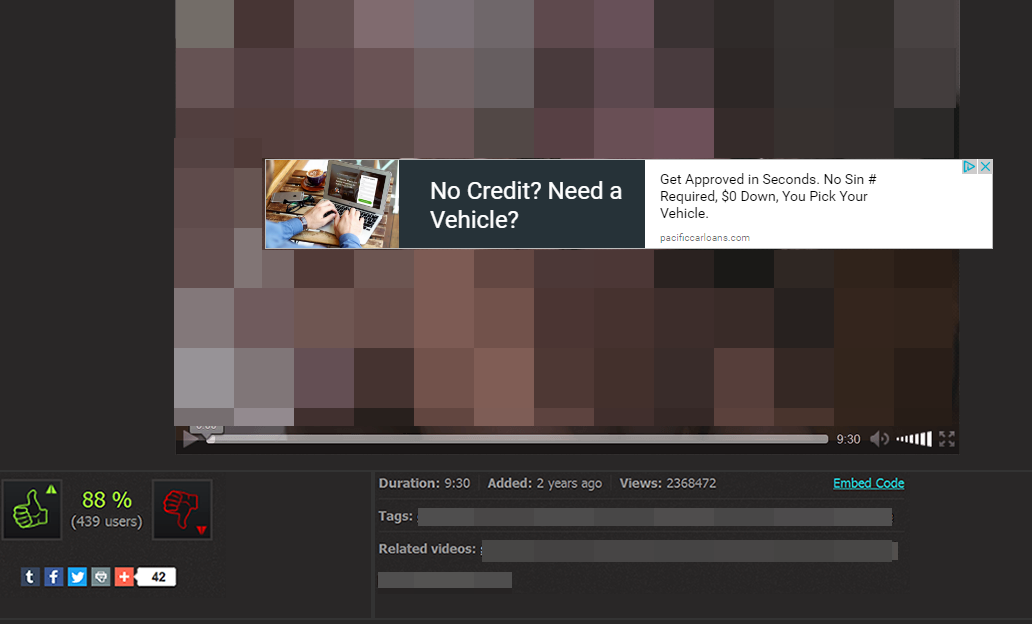

Figure 9: The hidden advert revealed with its placement over the video’s play button (click to enlarge)

One can actually show the hidden advert (as seen in Figure 9) simply by clicking in the browser’s address bar which results in the banner coming at the forefront. Similarly, giving focus back to the page by clicking anywhere in it will put the banner back in hidden mode again.

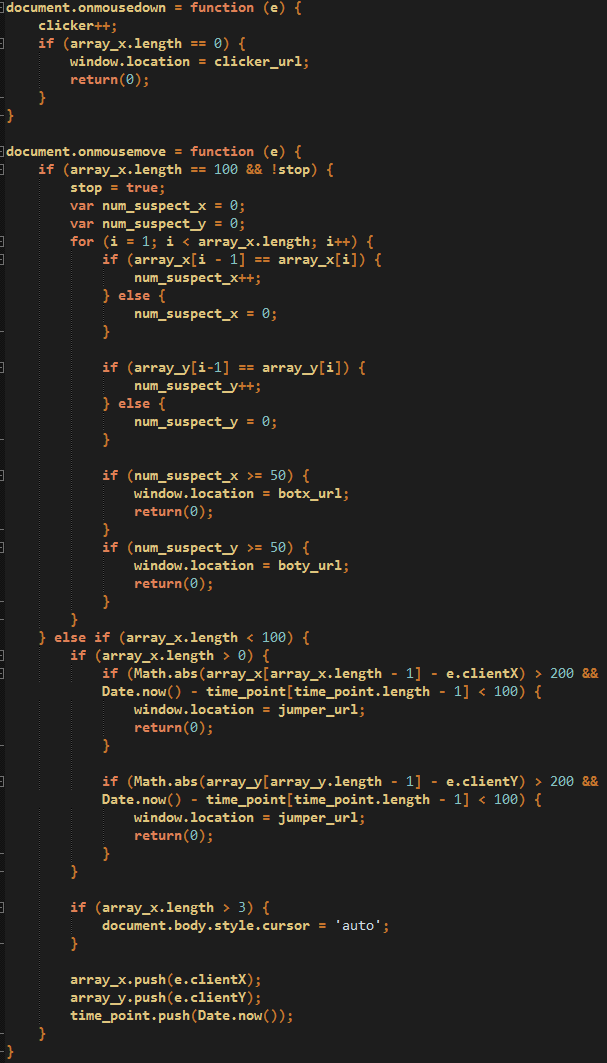

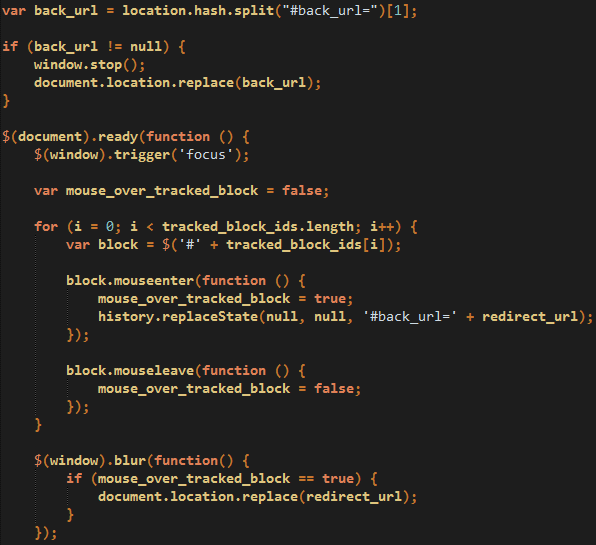

The crooks use JavaScript code to check for user activity, in particular mouse movements and clicks. Indeed, bots often do very programmatic and predictable actions that can be detected as patterns of non real human activity. The detector.js script from the fake blog will attempt to detect those emulated actions and immediately redirect the browser to Google’s homepage if it identifies any.

Figure 10: Checking for mouse activity to ensure clicks are legitimate (click to enlarge)

For instance, if a click is detected but the mouse hasn’t moved at all, this is a suspicious behaviour. Same goes for the mouse moving to specific onscreen coordinates at particular time frames. Malware that tries to emulate user activity will typically do some scrolls on screen or clicks, but those are usually not very random or unique enough and they get repeated from one infected machine to another.

Online criminals make money by exploiting weaknesses in systems and people which make them very aware of certain pitfalls that they need to avoid. We have seen in the past malware closing the security hole that allowed it to get in, or even remove a previous infection. Similarly, when it comes to ad fraud the bad guys know very well how to ensure they are getting paid and have less chances of getting caught.

It also clears the browser back button URL history such that the user cannot revisit the same page again:

Figure 11: Changing the ‘back URL’ based on mouse activity (click to enlarge)

If a real human clicked to view the non-existing video, they actually clicked on the hidden ad, thereby generating money for the crooks. Whoever got duped will soon realize that this was just a waste of time and that no video actually loaded. Users are less likely to report on this fraud due to the nature of the content they were trying to view.

In the meantime, the fraudsters behind this operation are making money for each view and click. Given that they only have to pay for cheap incoming traffic versus the more expensive Google Ads, this is a profitable business model.

Figure 12: Web traffic from fake blog to click fraud (click to enlarge)

Link with previous campaign

In January of 2016, we wrote about a clickjacking attack taking advantage of the new European law on browser cookies. Similarly, users were tricked into clicking on ‘I accept cookies’ which actually clicked on an ad banner and defrauded legitimate advertisers.

The domain names used then and now have a similar pattern with the word ‘webhosting‘ in it, which could be a coincidence of course, but is noteworthy since both campaigns use clickjacking to abuse Google AdSense.

Figure 13: Traffic capture from the European cookie clickjacking campaign

Another interesting aspect is the use of filters (i.e. filter.php, process.php) to weed out bots or machines that are already blacklisted. This was not something we had covered in our original blog post but by comparing with past captures, we can see the idea is very similar, although not as sophisticated.

Closing thoughts

There aren’t many industries that generate as many heated debates as the ad industry does. One argument that you will often hear is that ad agencies, networks and publishers still make money whether an ad is malicious or never was actually viewed by anyone. There is also a direct correlation between digital ad spend and ad fraud over the past few years.

This does not mean that the involved parties are desensitized to malware or fraud (they invest a lot of resources to combat that problem). In fact, treating them as ‘they’ is a poor choice since it assumes everyone is on the same level. We know that there are some networks/publishers that turn a blind eye – or worse – are directly affiliated with criminal gangs, while others are actually taking an active stance to fight malware and fraud.

The problem remains that there is an ever growing concern from both users (adopting ad blockers at a fast pace) and advertisers, getting less and less bang for their buck. Just like with malvertising, as long as there is an economic gain, criminals will keep on pursuing their abuse to exploit advertising as a unique and profitable fraud and infection vector.

We have notified Google and passed along the necessary information about this abuse of their ad platform.

Further reading:

- State of digital ad fraud 2017 [Slideshare] by Augustine Fou.

- Ad fraud 101 [PDF] Integral Ad Science

IOCs:

Gates:

stockwebhosting[.]com doctorwebhosting[.]com triwebhosting[.]com webhostingfashion[.]com

Fake blogs:

justhappymarriage[.]com myamericansofa[.]com instaautohire[.]com bugcurb[.]com bestautotariff[.]com pestdomination[.]com pleasedwedding[.]com nicewashing[.]com theusaappliance[.]com topcaraccidentals[.]com perfectpurification[.]com