In April, Xudong Zheng, a security enthusiast based in New York, found a flaw in some modern browsers in the way they handle domain names. While Chrome, Firefox, and Opera already have security measures in place to cue users that they might be visiting a destination they thought was legitimate, at that time these browsers did not flag a fake domain name that used all Latin look-alike characters taken from another foreign language. Zheng demonstrated this when he created and registered a proof-of-concept (PoC) page for the domain, аррӏе.com, which was written in pure Cyrillic characters.

What is a homograph attack?

A homograph attack is a method of deception wherein a threat actor leverages on the similarities of character scripts to create and register phony domains of existing ones to fool users and lure them into visiting. This attack has some known aliases: homoglyph attack, script spoofing, and homograph domain name spoofing. Characters—i.e., letters and numbers—that look alike are called homoglyphs or homographs, thus the name of the attack. Examples of such are the Latin small letter O (U+006F) and the Digit zero (U+0030). Hypothetically, one might register bl00mberg.com or g00gle.com and get away with it. But in this day and age, such simple character swaps could be easily detected.

In an internationalized domain name (IDN) homograph attack, a threat actor creates and registers one or several fake domains using at least one look-alike character from a different language. Again, hypothetically, one might register gοοgle.com, but not before swapping the Latin small letter O (U+006F) with the Greek small letter Omicron (U+03BF).

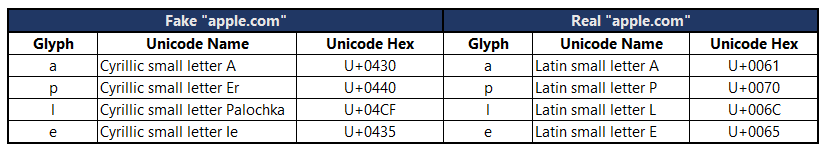

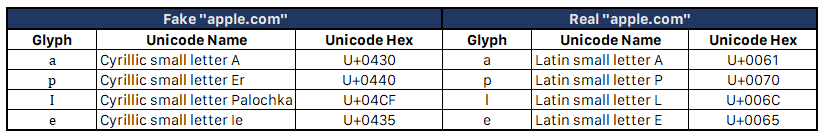

Zheng’s PoC is another example of an IDN homograph attack, so let’s list down each character he used to illustrate how this particular attack can be highly successful and dangerous if used in the wild. Interestingly, an operating system’s typeface of choice could make it easy or difficult for users to visually differentiate non-Latin characters from Latin ones.

Table 1: We used Segoe UI, Microsoft’s system-wide typeface, here.“>

To the human eye, these Cyrillic glyphs can easily be confused with their Latin counterparts. Computers, however, read these confusables differently, as we can see from the different hex codes assigned to them.

Table 2: We used San Francisco, Apple’s system-wide typeface, here. It’s worth noting that OSX distinguishes the Cyrillic small letter Palochka from the Latin small letter L; however, it cannot show the difference between the Latin small letter L with the Latin capital letter I, as per the text “Cyrillic small letter Ie”.“>

According to this bug report, it seems that even the system-wide font for Linux doesn’t distinguish confusable characters either.

The use of all-Cyrillic glyphs—or any other non-Latin characters for this matter—for domain names isn’t the problem. IDN has made it possible for internet users around the globe to create and access domains using their native language scripts. The problem is when these glyphs are misused to deceive internet users.

Is this a new form of online threat?

Homograph attacks have been around for years. As far as we know, Zhang’s PoC was the first of its kind to make headlines and spark a conversation among internet users.

Below are other examples of homographed domains and how they were used:

- To raise awareness, a security consultant highlighted the common misconception that sometimes a Latin capital letter I (U+0049) looks similar to a Latin small letter L (U+006C) by registering a fake Lloyds Bank website and adding an SSL certificate to it to make it look as legitimate as the real one.

- A security researcher from NTT Security shared his experience about a friend of his who received several Google Analytics spam containing the domain, secret[DOT]ɢoogle[DOT]com. The “ɢ” there wasn’t the Latin capital letter G (U+0047) but a Latin letter small capital G (U+0262).

- A security researcher from NewSky Security found an impersonated Adobe website serving the Betabot malware, pretending to be an Adobe Flash Player installer file. The threat actor used the Latin small letter B with Dot below (U+1E05) to replace the Latin small letter B (U+0062) in “adobe.com”.

How is this different from typosquatting?

Although typosquatting also uses visual tricks to deceive users, it relies heavily on users mistyping a URL in the address bar, hence, the “typo” in its name.

Are all homograph attacks just phishing attacks?

Not necessarily. Although homograph attacks usually involve phishing, threat actors could create fake yet believable websites for other fraudulent purposes or to introduce malware onto user systems, as is the case of the bogus Adobe website we mentioned earlier.

In this in-depth report about IDN homograph attacks, our friends at Symantec have noted that several homographed domains they found were either part of a malvertising network, hosting exploit kits and malicious mobile apps, or generated by botnets.

How can we protect ourselves from homograph attacks?

Browser tools have been created, such as Punycode Alert and the Quero Toolbar, to aid users in alerting them of potential homograph attacks. Users have the discretion of adopting them alongside the built-in security mechanisms in today’s browsers. However, no tool can replace vigilance when browsing online and a solid cybersecurity hygiene. This includes:

- Regularly updating your browser (They may be your first line of defense against homograph attacks)

- Confirming that the legitimate site you’re on has an EVC

- Avoid clicking links from emails, chat messages, and other publicly available content, most especially social media sites, without ensuring that the visible link is indeed the true destination.

Remember: Eyes open.

Stay safe!

Additional reading(s):

- ICANN Statement on IDN Homograph Attacks and Request for Public Comment

- Unicode Security Considerations and Mechanisms

- The Homograph Attack [PDF] by Evgeniy Gabrilovich and Alex Gontmakher

Resource: