Games and analytics services ran into one another headfirst recently, in a spat related to the game Conan Exiles.

Developers had to remove a tracking service, which allowed game developers to track where Steam players had come from. By generating an API key and integrating it into the game, developers could figure out which ad campaigns (for example) had directed gamers to Steam at first install.

From another game developer’s forum, where they too ended up removing the system:

Click to enlarge

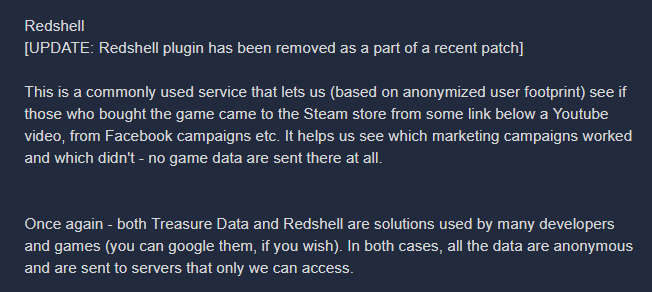

[UPDATE: Redshell plugin has been removed as a part of a recent patch]

This is a commonly used service that lets us (based on anonymized user footprint) see if those who bought the game came to the Steam store from some link below a Youtube video, from Facebook campaigns etc. It helps us see which marketing campaigns worked and which didn’t – no game data are sent there at all.

Once again – both Treasure Data and Redshell are solutions used by many developers and games (you can google them, if you wish). In both cases, all the data are anonymous and are sent to servers that only we can access. As far as Conan goes, the system in place ultimately led to bad reviews, and when the bad reviews start rolling in due to third-party apps, there can be only one end result:

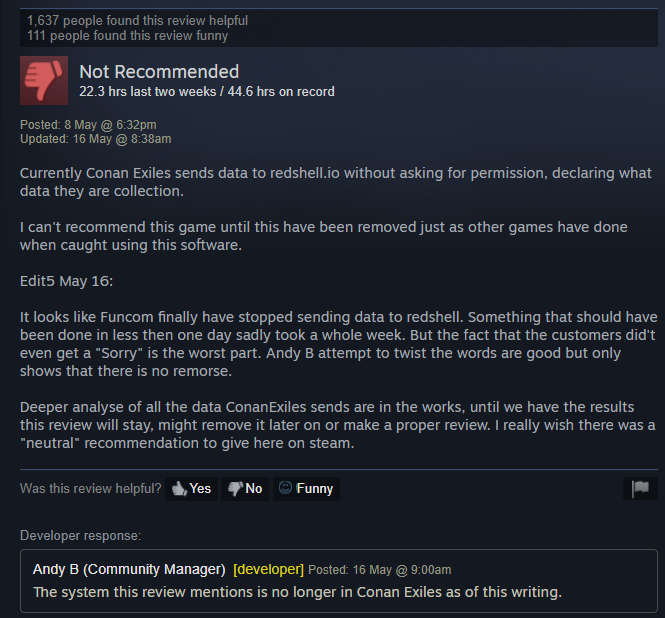

Click to enlarge

From the Community Manager:

The system this review mentions is no longer in Conan Exiles as of this writing. Some gamers are so fed up with third party tracking / analytics in games that they now curate Steam lists purely for games making use of said setups.

What’s fascinating to me is that gamers often have no idea exactly how much data a developer racks up even without third-party tools or analytics in place. Even in the case of Conan Exiles, there’s currently a lack of official servers so people are being encouraged to use third-party servers run by random admins. You’re being asked to place a lot of trust in someone who can simply decide to stop paying for hosting, and who also has full control over the game settings. What happens to all your cool stuff when the admin pulls the plug or decides their friend has a better claim to the land you built your castle on?

The answer is, “It’s probably all just gone out the window, sorry.” Yet as best I can tell, there aren’t as many aggrieved voices raised in relation to rogue admins or even the “anti-tamper” technology in place.

I’ve covered Privacy Policies at length in the past, so I won’t dwell on them here.

What I do want to do is give you a link to a talk I gave at Virus Bulletin 2017, all about the Virtual Worlds of Advergaming.

If you’re even remotely concerned about a system sending “how did they get here?” data to a game developer, you should be aware that marketing, advertisements, and even social engineering designed to throw ads at you in-game have existed for a long time. In fact, it’s already starting to bleed over to augmented and virtual reality.

Did you ever wonder why you’d been funneled down a narrow corridor in a shooter, then forced to crouch behind a branded energy drinks dispenser as the only piece of available cover in a gunfight?

Click to enlarge

Or why devs would place a huge billboard at the top of a hill you had to spend a few minutes hiking toward?

Click to enlarge

Maybe you just wondered if an in-game ad network dedicated to virtual titles was potentially susceptible to dubious ads like the mock-up below?

Click to enlarge

These are all things I’ve endeavored to cover in this talk.

Here’s the pitch:

As adverts in gaming (advergaming) ecosystems continue to become more sophisticated —while the game networks themselves have effectively become social networks—so too do the potential complications for parents, children, and gamers, who just want to play without worrying about where their data is going (and how it is being used). Attempts at blocking ads on closed gaming networks, tablets, and PC games have started to turn into the same type of turf war as seen on PC desktops, and forays into VR gaming have only made this more of an issue—the more potentially realistic the game experience, the harder it becomes to disassociate product advertising from the world around you.

This presentation explains: the different types of in-game ads (static, dynamic, through the line, below the line), how adverts have effectively broken simple processes for good, which specific types of advertising are used on certain platforms, and the gamification of people in the real world. It will also illustrate some of the tricks and techniques used by advertisers to ensure that gamers can’t avoid adverts as part of their gaming experience, and will compare the oldest forms of advergaming with the newest techniques, looking at how gamers trying to block ads have led to unskippable ads which form part of gameplay, and at what the future holds for VR/augmented in-game advertising.

Viewers should come away with a greater understanding of the types of advertising used in the systems they engage with on a daily basis, how that advertising may target family members in specific ways, which types of gaming are least/most susceptible to advergaming, how game developers manipulate gamers into seeing ads at specific times, and the informed choices available to reduce or eliminate forms of in-game ads they may feel uncomfortable with. I’d like to think I got the job done for the attendees of Virus Bulletin 2017, shining as big a light as I could on some of these practices in the 25 minutes available to me. You can read the full paper about the Virtual Worlds of Advergaming here.

Otherwise, you can simply watch the talk (with a few minutes of the opening missing due to a technical hitch) below.