Thanks to Jerome Boursier for contributions.

Post GDPR, many social media platforms will ask end users to consent to some form of tracking as a condition of using the service. It’s easy to make assumptions as to what that means, especially when the actual terms of service or data policy for the service in question is tough to find, full of legal jargon, or just long and boring. Part of the shock of Facebook stories was in discovering just how expansive their consent to tracking really was. Let’s take a look at what can happen after you hit OK on a new site’s Terms of Service.

What we think they’re doing

Most commonly, users think that social media sites limit their tracking to actual interactions with the site while logged in. This includes likes, follows, favorites, and general use of the site as intended. Those interactions are then analyzed to determine a user’s rough interests, and serve them corresponding ads.

We asked some non-technical Malwarebytes staffers what they thought popular companies collected on them and got the following responses:

“Hmm I would assume just my name, birthday, trends in the hashtags I use, and locations I’m at. Nothing else.”

“As far as IG goes, I’m guessing they collect data on the hashtags I follow and what I look at because all the ads are home improvement ads.”

While these are common use cases for tracking, innovations in user surveillance have allowed companies to take much more invasive actions.

What they’re actually doing

The Cambridge Analytica reports were quite shocking, but in theory their data practices were actually a violation of the agreement they had with Facebook. Somewhat more concerning are actions that Facebook and other social media companies take overtly with third parties, or as part of their explicit terms of service.

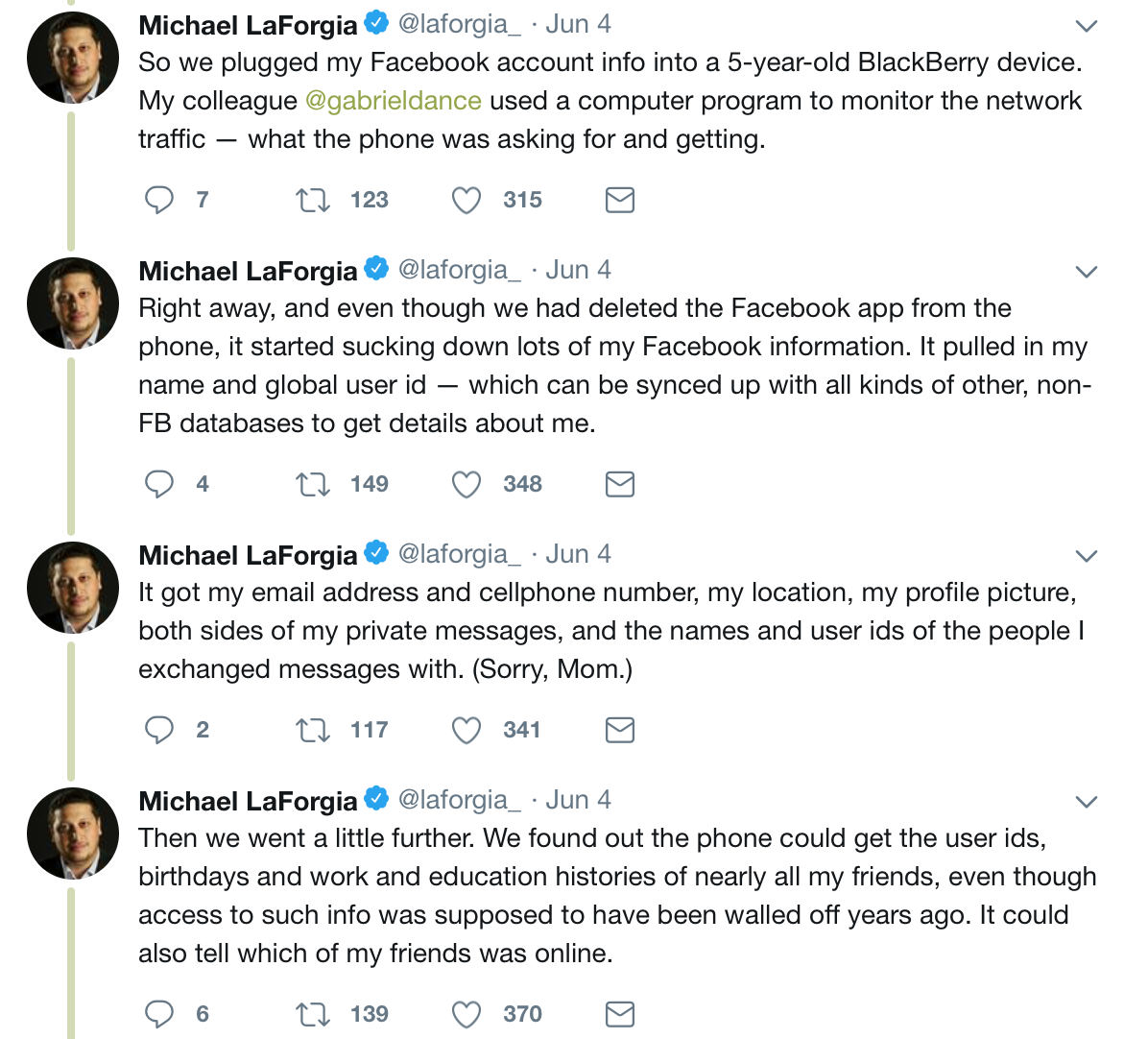

In June 2018, a New York Times report revealed partnerships between Facebook and mobile device manufacturers allowed data collection on your Facebook friends, irrespective of whether those friends had allowed data sharing with third parties. This data collection varied by device manufacturer, and most were relatively benign. Blackberry, however, seemed to go beyond what most of us expect to be collected when we log in:

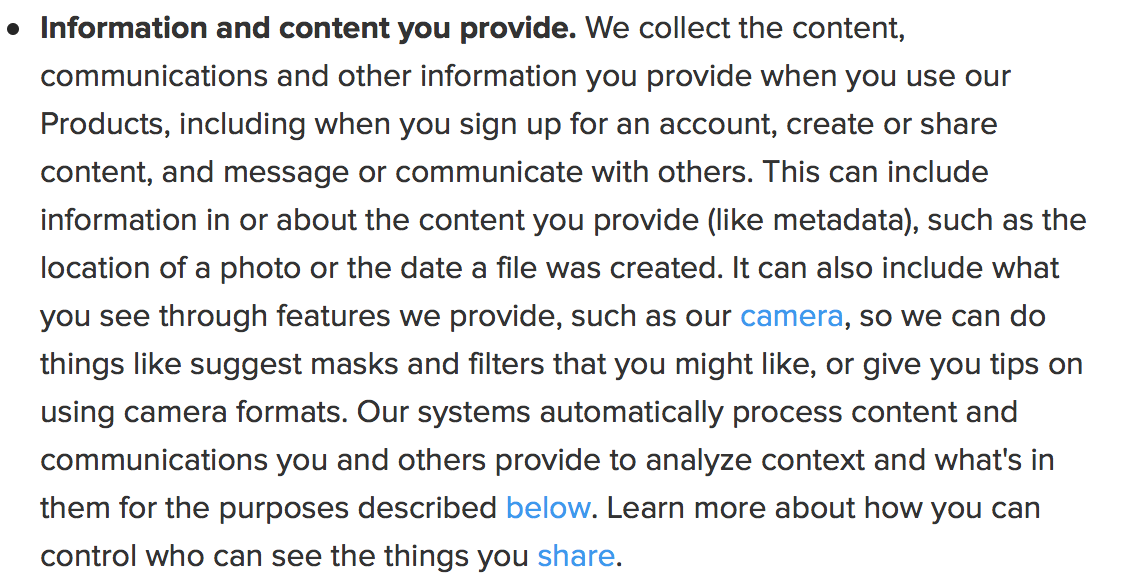

Facebook has been known for years to have somewhat creepy partnerships like this. But what about other platforms? Instagram has an interesting paragraph in its terms and conditions:

Does communications include direct messages? How long is this information stored, where, and under what conditions? It could be perfectly secure and anonymized, but it’s difficult to tell because Instagram is a little vague on these points. Companies tell us what they collect consistently but they don’t always tell us why or disclose retention conditions, which makes it difficult for a user to make a proper risk assessment for allowing tracking.

Outside of the Facebook family of products, Pinterest does some data sharing that you might not expect:

A reasonable user might not expect that when consent to tracking connected with a Pinterest account, they would also agree to offsite tracking. Pinterest does stand out, however, by presenting well organized and clear information followed by simple opt-out instructions after each section.

What they might be doing

Most platforms that engage in user tracking do so in ways that raise concern, but are not overtly alarming. Abuses we’ve heard about tend to center on the tracking company sharing information with third parties. So what might happen if the wrong third party gains access to this data?

In 2016, a Pro Publica investigation was able to use Facebook ad targeting to create a housing ad that excluded minorities from seeing it. (This probably violates the US Fair Housing Act.) Using user data to discriminate in plausibly deniable ways predates the Internet, but the unprecedented volume of data collected makes schemes by bad actors much more efficient and easy to launch.

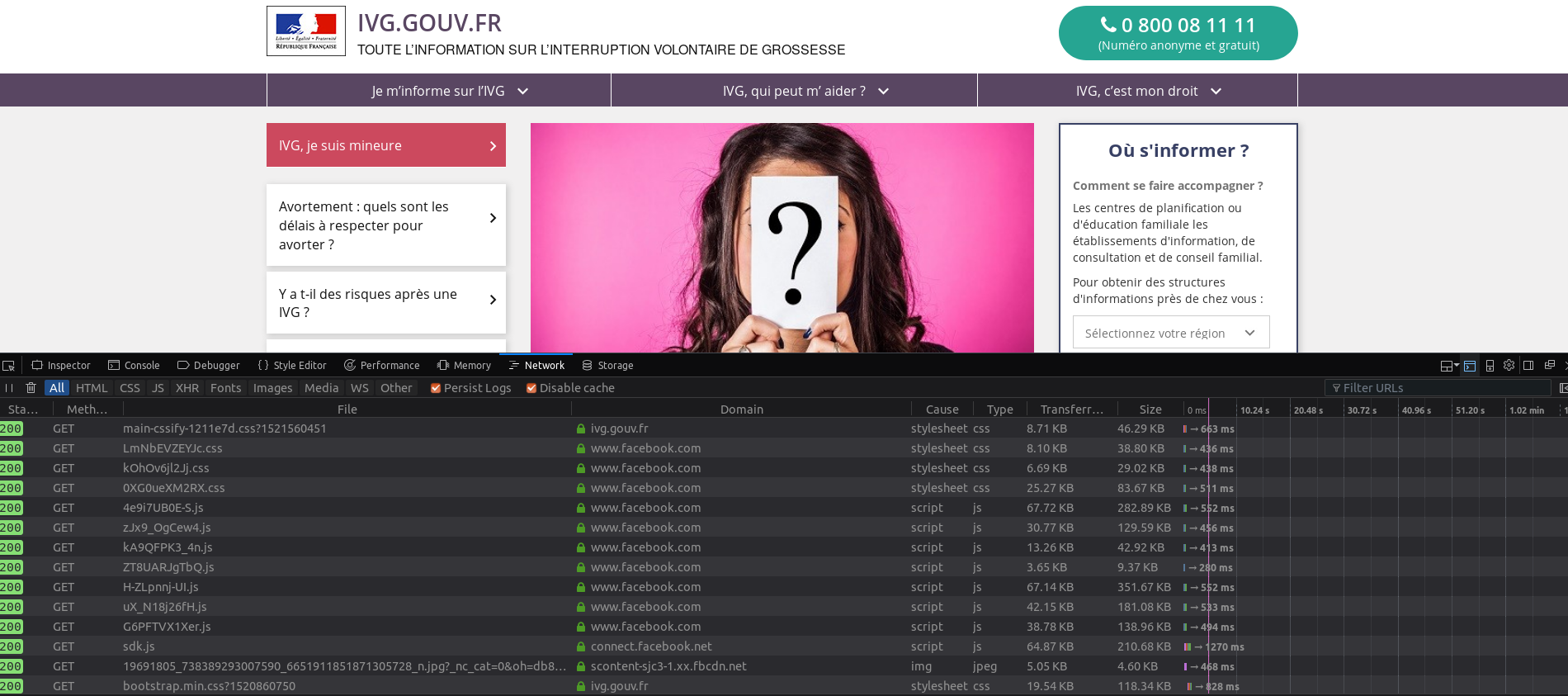

A more speculative harm is the use of tracking tags on sensitive websites. In France, a government website providing accurate information on reproductive health services was using a Facebook tracker. A “trusted partner” receiving user metadata, as well as which sections of the site that user clicks on, has the potential to be profoundly invasive. From a risk mitigation perspective, a user with a Facebook account might not have anticipated this sort of tracking when they initially consented to Facebook’s terms of service.

A common counter to complaints regarding user tracking is, “Well, you agreed to their terms, so you should have expected this.” This is arguably applicable to basic metadata collection and targeted ads, but is it reasonable to expect a Facebook user to understand that their off-platform browsing is subject to surveillance as well? User tracking has progressed so far in sophistication that an average user most likely does not have the background necessary to imagine every possible use case for data collection prior to accepting a user agreement.

What you can do about it

If any of the above examples make you uncomfortable, check out how to secure some common social media platforms using internal settings. If you want to implement additional technical solutions, browser extensions like Ghostery and the EFF’s Privacy Badger can prevent trackers from sucking up data you would prefer not to hand over.

Messenger services are a bit harder to transition away from, but not impossible. Signal is a well-regarded messenger app with end-to-end encryption, and a history of respecting user privacy. Alternatively, Wire can provide a more business-oriented alternative, with screen sharing, file sharing, and access role management.

Most important is to stay suspicious when accessing a new platform. No one can mishandle data that you never agree to hand over to begin with. Stay vigilant, stay safe, and enjoy your social media platforms knowing exactly how your data is being used.