Last week, Apple introduced several new privacy features to its latest mobile operating system, iOS 13. The Internet, predictably, expressed doubt, questioning Apple’s oversized influence, its exclusive pricing model that puts privacy out of reach for anyone who can’t drop hundreds of dollars on a mobile phone, and its continued, near-dictatorial control of the App store, which can, at a moment’s notice, change the rules to exclude countless apps.

At Malwarebytes, we sought to answer something different: Do the new iOS features actually provide meaningful privacy protections?

The short answer from multiple digital rights and privacy advocates is: “Yes, but…”

For example: Yes, but Apple’s older phones should not be excluded from the updates. Also: Yes, but Apple’s competitors are not likely to follow. And more broadly: Yes, but Apple is giving users a convenient solution that does not address a core problem with online identity.

Finally: Yes, but Apple can go further.

Apple’s new single sign-on feature

At Apple’s WWDC19 conference in San Jose last week, Senior Vice President of Software Engineering Craig Federighi told audience members that the latest iOS would give Apple users two big privacy improvements: better protection when signing into third-party services and apps, and more options to restrict location tracking.

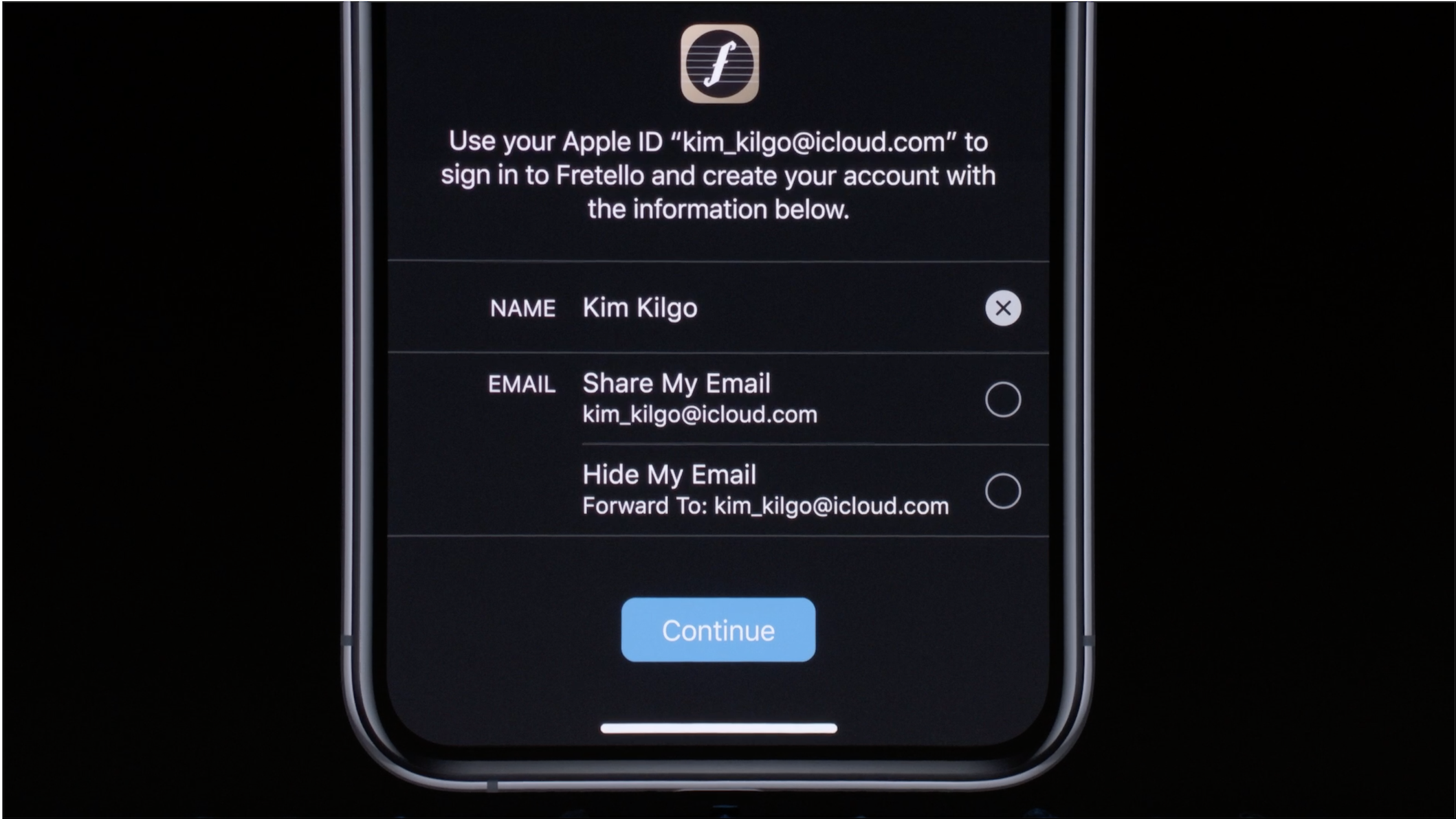

Apple’s Single Sign-On (SSO) option will allow users to sign into third-party platforms and apps by using their already-created Apple credentials. Called “Sign in with Apple,” Federighi described the feature not so much as a repeat of similar features provided by competitors Google and Facebook, but as a response.

Standing before a projected display of two separate blue rectangles, one reading “Sign in with Facebook,” the other “Sign in with Google,” Federighi told the audience, “We’ve all seen buttons like this.”

While convenient, Federighi said, these features can also compromise privacy, as “your personal information sometimes gets shared behind the scenes, and these logins can be used to track you.” Behind Federighi, the presentation revealed all the types of information that get shuffled around without a user’s full understanding: Full names, gender, email addresses, events attended, locations visited, hometown, social posts, and shared photos and videos.

Federighi said “Sign in with Apple” locks that data dispersal down.

“Sign in with Apple” lets Apple users log into third-party apps and services by using the Face ID or Touch ID credentials created on their device. The SSO feature also gives Apple users the option to provide third parties with “relay” email addresses—randomly-generated email addresses created by Apple that serve as forwarding addresses, giving users the option to keep private their personal email address while still receiving promotional deals from a company or service. Further, relay addresses will not be repeated, and Apple will generate a new relay for each new platform or app.

Privacy advocates welcomed the feature but warned about over-reliance on Apple as the one true purveyor of privacy.

“Apple’s new sign-in service is definitely a step in the right direction, but it’s important to understand who it’s protecting you from,” said Gennie Gebhart, associate director of research at Electronic Frontier Foundation. “In short, this kind of feature protects you from all sorts of scary third parties but does not necessarily protect you from the company offering it—in this case, Apple.”

Apple has scored positively with EFF’s annual “Who Has Your Back” report, which, for years, evaluated major tech companies for their willingness to fight overbroad, invasive government requests for user data.

But protecting user data from government requests and protecting it from corporate surveillance are different things.

Luckily, Gebhart said, Apple has promised not to use the information it gleans from its SSO feature to track user activity or build profiles from online behavior. But, Gebhart said, the same can’t be assumed from other big tech companies including Google and Facebook.

“[I]t’s important to remember for other SSO services like Facebook’s and Google’s that, even if they implement cool privacy-protective features like Apple has, that won’t necessarily protect you from Facebook or Google tracking your activity,” Gebhart said.

As to whether those companies will actually follow in Apple’s footsteps, Nathalie Maréchal, a senior research analyst at Ranking Digital Rights, seems doubtful, as those competitors rely on entirely different business models.

“Google, Apple’s main competitor in the smartphone market, relies on pervasive data collection at a massive scale not only to sell advertising, but also to train the algorithms that power its products, such as Google Maps,” Maréchal said. “That’s why Google collects as much data as it possibly can: that data is the raw material for its products and services. I don’t see Google shifting to a model where it collects as little information as possible—as Apple says it does—anytime soon.”

That said, Maréchal still commended Apple for offering relay email addresses in its SSO feature.

“This makes the process much more user-friendly, and makes it even harder for data brokers and advertising networks to connect all of someone’s online activity and create a detailed file about them,” Maréchal said.

Yet another researcher, who said it was good to see Apple taking “practical steps” to protect online identities, warned about a larger problem: The increased dependence on a user’s identity as the de facto credential for accessing all sorts of online services and platforms.

“We are seeing more and more websites and apps pushing us to identify ourselves; while sometimes this may be appropriate, it comes along with dangers,” said Tom Fisher, a researcher at Privacy International. “It can be a tool for tracking people across sessions, for instance.”

Fisher continued: “There’s a need for more thought not only on how identification systems can protect people’s privacy, but also when it is appropriate to ask people to identify themselves at all.”

Apple’s new option for location privacy

Apple’s second big feature will give its users the option to more closely manage how their location is tracked by various third-party apps.

With the update to iOS 13, users can choose to share their location “just once” with an app. That means that, if users choose, any service that requests location information—whether it be Yelp when recommending nearby restaurants, Uber when finding nearby drivers, or Fandango when locating nearby movie theaters—will be allowed to access that information just once, and every subsequent request for location information must be approved by the user on an individual basis.

Maréchal called this an important development. She said many apps that request location information provide convenient services for users, and users should have the option to choose between that convenience and that potential loss of privacy. That decision, she said, is unique to each user.

“That’s a very contextual decision and I’m glad to hear that Apple is giving its users more nuanced options than simply ‘on,’ ‘off,’ or ‘only when the app is in use,’” Maréchal said. “For example, I might not want to share my location with Yelp while checking opening hours for a business in my home city, because the privacy trade-off isn’t worth it, and then might share my location while traveling the following week because I don’t know the city I’m visiting well enough to know how far a restaurant is from me.”

Further steps?

When interviewed for this piece, every researcher agreed: Apple’s newest features provide simple, easy-to-use options that can leave users more informed and more in control of their online privacy.

However, another response came up more than once: Apple can—and should—go further.

These responses are not unusual, and, in fact, they follow in the footsteps of all advocacy work, particularly in online privacy. Earlier this year, it was Mozilla, the privacy-forward, nonprofit developer of the web browser Firefox, that asked Apple to do better by its users in protecting them from invasive online tracking. Similarly, it is privacy advocates and researchers who have the most thought-out ideas on protecting user privacy. These researchers had a few ideas for Apple.

First, Maréchal said, Apple should provide “transparency” reports—the way it already does for the government requests it receives for user data—that disclose how third-party apps collect Apple users’ information. She said Apple’s marketing tagline (“What happens on your iPhone, stays on your iPhone”) is only true for the data Apple itself collects, “but it’s not true of data collected by third party apps.”

A Washington Post article last month revealed this to an alarming degree:

“On a recent Monday night, a dozen marketing companies, research firms and other personal data guzzlers got reports from my iPhone. At 11:43 p.m., a company called Amplitude learned my phone number, email and exact location. At 3:58 a.m., another called Appboy got a digital fingerprint of my phone. At 6:25 a.m., a tracker called Demdex received a way to identify my phone and sent back a list of other trackers to pair up with.”

Fisher raised a separate issue regarding Apple’s security updates: Who gets left behind? At such a high price point for the devices (The oldest iPhone model for sale on Apple’s website that is iOS 13 compatible, the Apple iPhone 7, starts at $449), Fisher said, “What happens to people who can’t afford Apple’s expensive products: Are they then left only with access to more invasive ways of identifying themselves?”

Another one of Maréchal’s suggestions could address that problem.

“I would also like some clarity about how long a new iPhone will be guaranteed to receive software updates, as well as a commitment to providing security updates specifically for at least five years,” Maréchal said. “Given how expensive new iPhones can be, customers should know how long the device will be safe to use before they purchase it.”

While this idea does not fix Fisher’s concerns, it at least gives users a better understanding about what they can expect for their own privacy years later. Any company’s decision to put users in more control of their privacy rights is a decision we can sign onto.