Researchers from Dell Secureworks saw a new feature in TrickBot that allows it to tamper with the web sessions of users who have certain mobile carriers. According to a blog post that they published early last week, TrickBot can do this by “intercepting network traffic before it is rendered by a victim’s browser.”

If you may recall, TrickBot, a well-known banking Trojan we detect as Trojan.TrickBot, was born from the same threat actors behind Dyreza, the credential-stealing malware our own researcher Hasherazade dissected back in 2015. Secureworks named the developers behind TrickBot as Gold Blackburn.

TrickBot rose into prominence when it rivaled Emotet and became the number one threat for businesses in the last quarter of 2018.

Before it took yet another step up its evolutionary ladder, TrickBot already has an impressive repertoire of features, such as a dynamic webinject it uses against financial institution websites; a worm module; a persistence technique using Windows’s Scheduled Task; the ability to steal data from Microsoft Outlook, cookies, and browsing history; the means to target point-of-sale (PoS) systems; and the capability to spread via spam messages and moving laterally within an affected network via the EternalBlue, Eternal Romance, or the EternalChampion exploit.

Now, more recently, the same webinject feature is used against the top three US-based mobile carriers: Verizon Wireless, T-Mobile, and Sprint. Augmentation to accommodate attacks against users of these companies was added to TrickBot on August 5, August 12, and August 19, according to Dell Secureworks.

How does the attack work?

When users of affected systems decide to visit legitimate websites of Verizon Wireless, T-Mobile, or Sprint, TrickBot intercepts the response from official servers and passes it on to the threat actors’ command-and-control (C&C) server, jump starting its dynamic webinject feature. The C&C server then injects scripts—specifically, HTML and JavaScript (JS) scripts—within the affected user’s web browser, consequently altering what the user sees and doesn’t see before the web page is rendered. For example, certain texts, warning indicators, and form fields may be removed or added, depending on what the threat actors are trying to achieve.

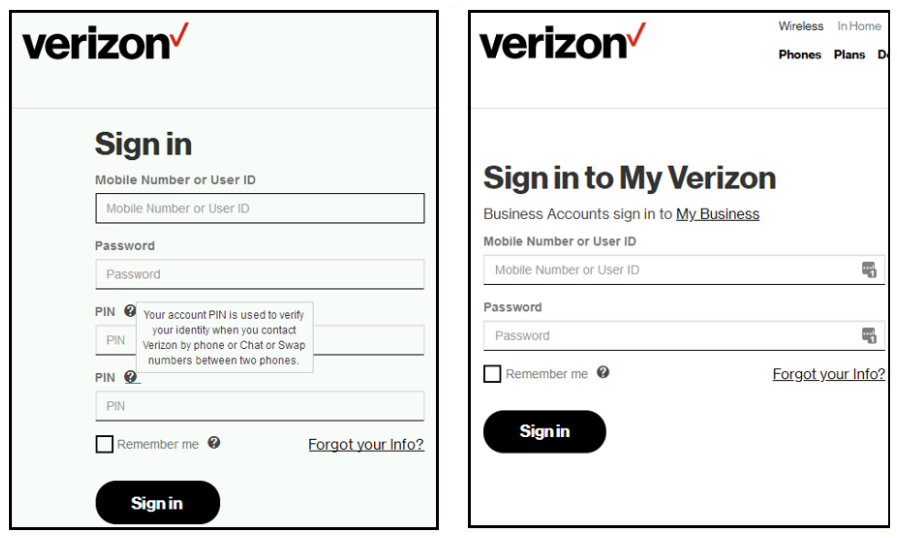

Dell Secureworks researchers were able to capture proof of certain changes TrickBot make on the original page of mobile carrier sites.

Above is a side-by-side comparison of Verizon Wireless’s sign in page before (image of the right) and after (image on the left) TrickBot tampered with it. Aside from some texts missing, notice also new added fields, specifically those asking for PIN numbers.

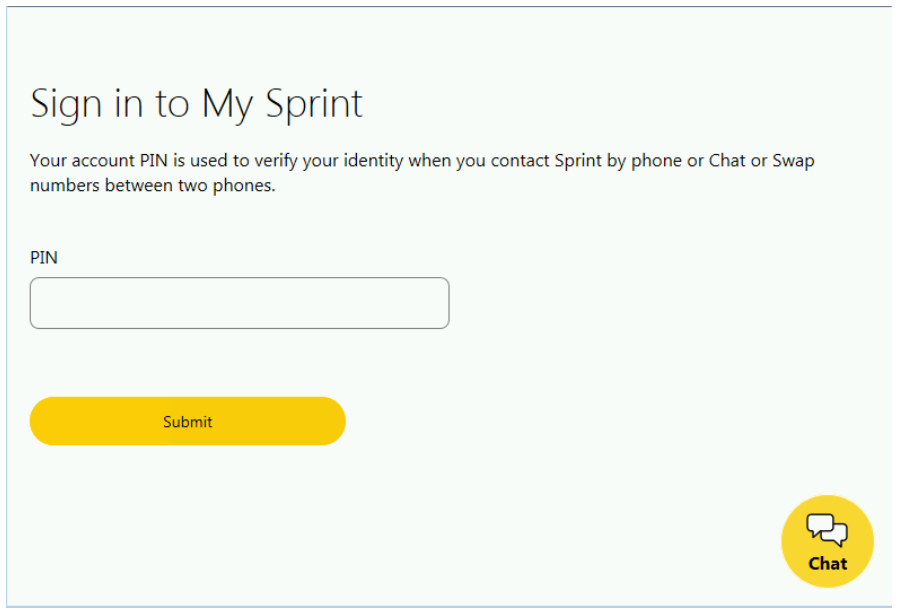

In the case of Sprint, the change is more subtle and quite seamless: an additional PIN form displays once users are able to successfully sign in with their user name and password.

The sudden targeting of mobile phone PINs suggests that threat actors using TrickBot are showing interest in getting involved with certain fraud tactics like port-out fraud and SIM swap, according to the researchers.

A port-out fraud happens when threat actors call their target’s mobile carrier to request the target’s number be switched or ported over to a new network provider. SIM swapping or SIM hijacking works in a similar fashion, but instead of changing to a new provider, the threat actor requests for a new SIM card from the carrier that they can put in their own device.

These will cause all calls, MMS, and SMS supposedly for you to be sent to the threat actor instead. And if their target is using text-based two-factor authentication (2FA) on their online accounts, the threat actor can easily intercept company-generated messages to gain access to those accounts. This results in account takeover (ATO) fraud.

Such a scam is typically done when threat actors already got a hold of their target’s credentials and wish to circumvent 2FA.

How to protect yourself from TrickBot?

So as not to reinvent the wheel, we implore you, dear Reader, to go back and check our post entitled TrickBot takes over as top business threat wherein we outlined remediation steps that businesses (and consumers alike) can follow. This post also has a section on preventative measures—ways one can lessen the likelihood of TrickBot infection in endpoints—starting with regular employee education and awareness campaigns on the latest tactics and trends about the threat landscape.

Note that Malwarebytes automatically detects and removes TrickBot without user intervention.

I think I may have fallen victim to this. What now?

The best action to take is to call your mobile carrier to report the fraud, have your number blocked, and consider requesting a new number. You can also report the scammers or fraudsters to the FTC.

Go ahead and change the passwords of all your online accounts that you have tied in with your phone number.

You might also want to consider using stronger authentication methods, such as the use of time-based one-time passwords (OTP) 2FA—Authy and Google Authenticator comes to mind—for accounts that hold extremely sensitive information about you, loved ones and friends, and your business or employees.

Enable a PIN on mobile accounts.

Lastly, familiarize yourself with the ways you can limit the possibility of a port out or SIM swap attack happening again. WIRED produced a brilliant story on how to protect yourself against a SIM swap attack while Brian Krebs over at KrebsOnSecurity has a piece on how to fight port out scams.

As always, stay safe, everyone!