The Internet of Things (IoT) is a term used to describe a wide variety of devices that are connected to the Internet to improve user experience. For example, a doorbell becomes part of the IoT when it connects to the Internet and allows users to see visitors outside their door.

But the way in which some of these IoT devices connect invites serious security and privacy concerns. This has led to pleas for laws and regulation in the production and marketing of IoT devices, including increased security features and better visibility into the security of those features.

Our loyal readers have seen our regular complaints about the built-in security of IoT devices and know how concerned we are about products that are designed to optimize functionality and cost over security. Many manufacturers expect consumers to care more about ease-of-use than about security.

But while this may be true for many consumers, the apparent indifference can also be explained by a lack of comparable options. If consumers were given the choice between a device that’s cheap, easy to use, and insecure and a device that’s a bit more costly but keeps users protected—our bet is there’d be a good chunk of consumers who’d select the more secure option.

While some states and countries do have laws demanding manufacturers produce “safe” products, this doesn’t help consumers in making a choice. At best, it limits their choice as some unsafe products will not make it to the market. To help users make an informed decision, some countries have decided to introduce a new cybersecurity labeling scheme (CLS) that provides consumers with information about the security of connected smart devices.

Countries introducing a cybersecurity labeling scheme

In November 2019, Finland became the first country in Europe to grant information security certificates to devices that passed the required tests. Their reasoning was that the security level of devices in the market varies a lot, and there’s no easy way for consumers to know which products are safe and which are not. As a service to the public, a website was launched to make it easy to find information about the devices that have been awarded the label.

On January 27, 2020, the UK’s Digital Minister Matt Warman announced a new law to protect millions of IoT users from the threat of cyberattack. The plan is to make sure that all consumer smart devices sold in the UK adhere to rigorous security requirements for the Internet of Things (IoT).

Shortly after the UK, the Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) announced plans to introduce a new Cybersecurity Labeling Scheme (CLS) later this year to help consumers make informed purchasing choices about network-connected smart devices.

As part of the initiative, CLS will address the security of IoT devices, a growing area of concern. The CLS, which is a first for the Asia-Pacific region, will first be introduced to two product types: WiFi routers and smart home hubs.

Recommended reading: 8 ways to improve security on smart home devices

The goals of a cybersecurity labeling scheme

The cybersecurity labeling scheme will be aligned to globally-accepted security standards for consumer Internet of Things products. It will mean that robust security standards will be introduced from the design stage and not bolted on as an afterthought.

The scheme proposes that such devices should carry a security label to help consumers navigate the market and know which devices to trust, and to encourage manufacturers to improve security. The idea is that—similar to how Bluetooth and WiFi labels help consumers feel confident their products will work with wireless communication protocols—a security label will instill confidence in consumers that their device was built according to security standards.

The Singapore CLS is a first-of-its-kind cybersecurity rating system in the APAC region, and is primarily aimed at helping the consumers make informed choices. The rating of a product will be decided on a series of assessments and tests including, but not limited to:

- Meeting basic security requirements (e.g. unique default passwords)

- Adherence to software and hardware security-by-design principles

- Common software security vulnerabilities should be absent

- Resistant to basic penetration testing activity

The same is true for the law that is under preparation for the UK. Their primary security requirements are:

- All consumer Internet-connected device passwords must be unique and not resettable to any universal factory setting.

- Manufacturers of consumer IoT devices must provide a public point of contact so anyone can report a vulnerability, and it will be acted on in a timely manner.

- Manufacturers of consumer IoT devices must explicitly state the minimum length of time for which the device will receive security updates at the point of sale, either in store or online.

As you can see in both cases, the main worry was the omnipresence of default passwords that were the same for a whole series of devices. And on top of that, users were not clearly informed that they needed to change the default password, and often it was hard to change them for the average user.

Optimizing the CLS

We applaud the efforts made by governments to improve on the overall security of IoT devices, but there are some improvements we would like to suggest.

- The Finnish site is available in Finnish and Swedish. For an outsider, it is hard to make out which products are approved and why. An English version would be a big step forward.

- The laws in the UK and California are a good start but could have been more restrictive. And they don’t inform a customer about the security of a device when they are looking to buy from a web shop that might be abroad.

- The Singapore CLS for now focuses on routers and smart home hubs because they consider them the gateways to the rest of the household. While this makes sense, it is a limited scope.

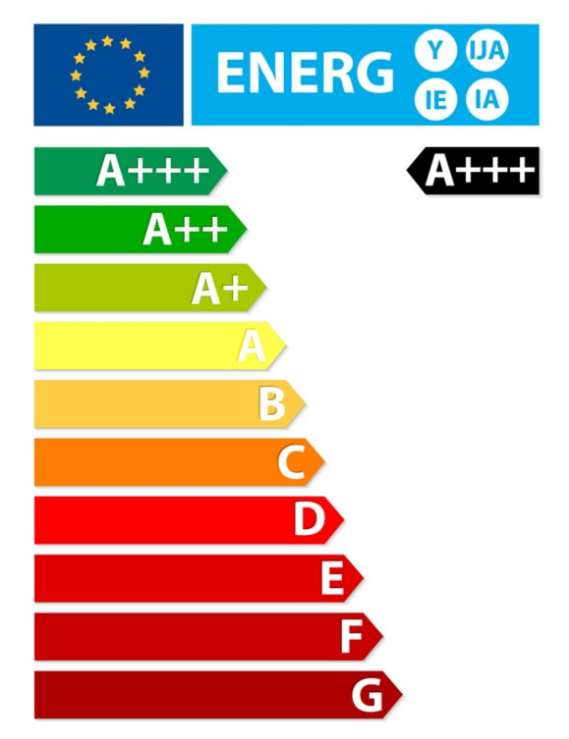

What all these regulations have in common is that they only inform the customer whether a device has passed muster in a certain state or country. Certainly, we can come up with a global scheme that gives customers a security level between “don’t buy this” and “very safe” like we have for energy efficiency in the EU.

But let’s rejoice for now that these governments are making a start in a much-needed effort to improve devices and inform customers. Let us hope that the various security labeling schemes will help consumers make an informed choice and drive manufacturers to focus more on security. And that other governments will follow their examples.

Stay safe, everyone!