In the last few weeks, there has been an upswing in people receiving threatening, extortion email messages, demanding payment to avoid release of sensitive information. Most of the time, these emails are what we call “sextortion” emails, as they claim that malware on your computer has captured embarrassing photos of you through the webcam, but there can be other variants on the same theme.

These extortion emails are nothing new, but with the recent increase in frequency, many people are looking for guidance. If you have received such an email message and want to know how you should respond, you’re in the right place. Read on!

Extortion claims

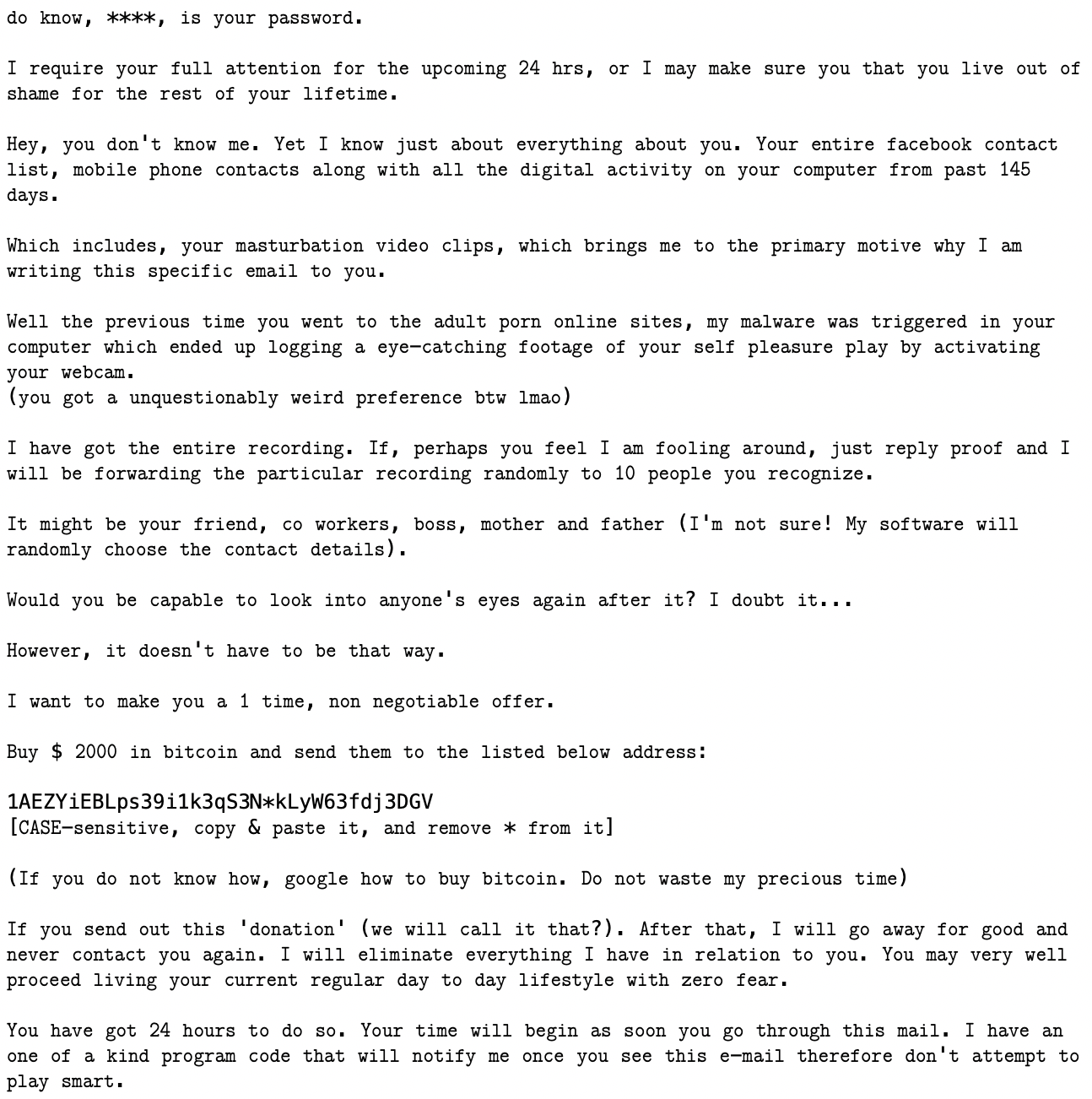

These email messages are not all exactly the same, but they do have fairly common characteristics. Consider the following example:

This is fairly representative of many examples. It starts out by telling you that the scammer knows one of your passwords, and the password really IS one of your passwords, which immediately ratchets up the fear and puts you in a mindset to believe that the rest of the message is also true. (Hint: it is not.)

Next, it tells you that the scammer knows other things about you, including photos of you doing something embarrassing, captured through malware on the computer. The message threatens to send these photos to people you know. Some variants may not involve this kind of “sextortion,” but the general pattern of doing something damaging with data stolen from the user is the same.

In order to prevent this, the scammer demands to be paid, usually in a currency called Bitcoin. There’s usually a time limit given for the payment, to really put the pressure on and encourage fast action rather than seeking help.

Are the extortion claims true?

With one exception, none of this is true. There is no malware involved. The scammer does not have any of the claimed information. If you don’t pay the demanded sum, nothing bad will happen. For the most part, these messages can simply be ignored.

However, the one part that is true is the password—which is the part that makes everything else seem more believable. The password did not, however, come from malware on the computer. Instead, it came from a third-party data breach.

What happens is that a site you have an account on gets breached, and someone is able to extract a bunch of email addresses and passwords. How this happens is not particularly important for our purposes here, but the effect is that two pieces of your personal information may have been published to various “dark web” sites: your email address and a password used with an account associated with that email address.

This is very similar to someone writing your phone number on the wall in a bathroom stall: it becomes public knowledge, for anyone who knows where to look, and it can lead to a lot of harassment.

Once this information has become public knowledge, criminals can take these lists and send mass email messages to everyone on the list, including the password associated with their email message. This is the real source of the seed of truth in these messages, not the fictitious malware the scammers want you to believe you’re infected with.

So I can ignore this, right?

Well, yes and no. Yes, the threat itself is an empty one, since there’s no malware. However, there’s a real danger under the surface: you have a password that has become public knowledge!

If the password provided is an old one that you are no longer using, then you’re golden. You’ve got no need to do anything further. However, for many people, the password is one that is still in active use, and that presents a problem. This particular scammer decided to use the password to scare you, but there are other criminals out there who might decide to use it for more nefarious purposes, like taking over your online life!

To prevent this from happening, there are a few steps you’ll need to take.

Step 1: Change your password

First and foremost, on any account using the password that was provided, change your password. While you’re at it, though, let’s make sure that it’s a good strong one. The best passwords are long, random ones… for example, “vdBdq8GoDh8ELGm$qRdgXVTq.” The longer the better.

It’s also important to use a different password on every site. Because password breaches will always happen, if you use the same password on multiple sites, that can lead to a breach on one site making it possible for an attacker to access your accounts across many different sites.

Okay, I hear you. No, I’m not expecting you to memorize ridiculous passwords for every site you have an account on. There’s a solution to that problem.

Step 2: Use a password manager

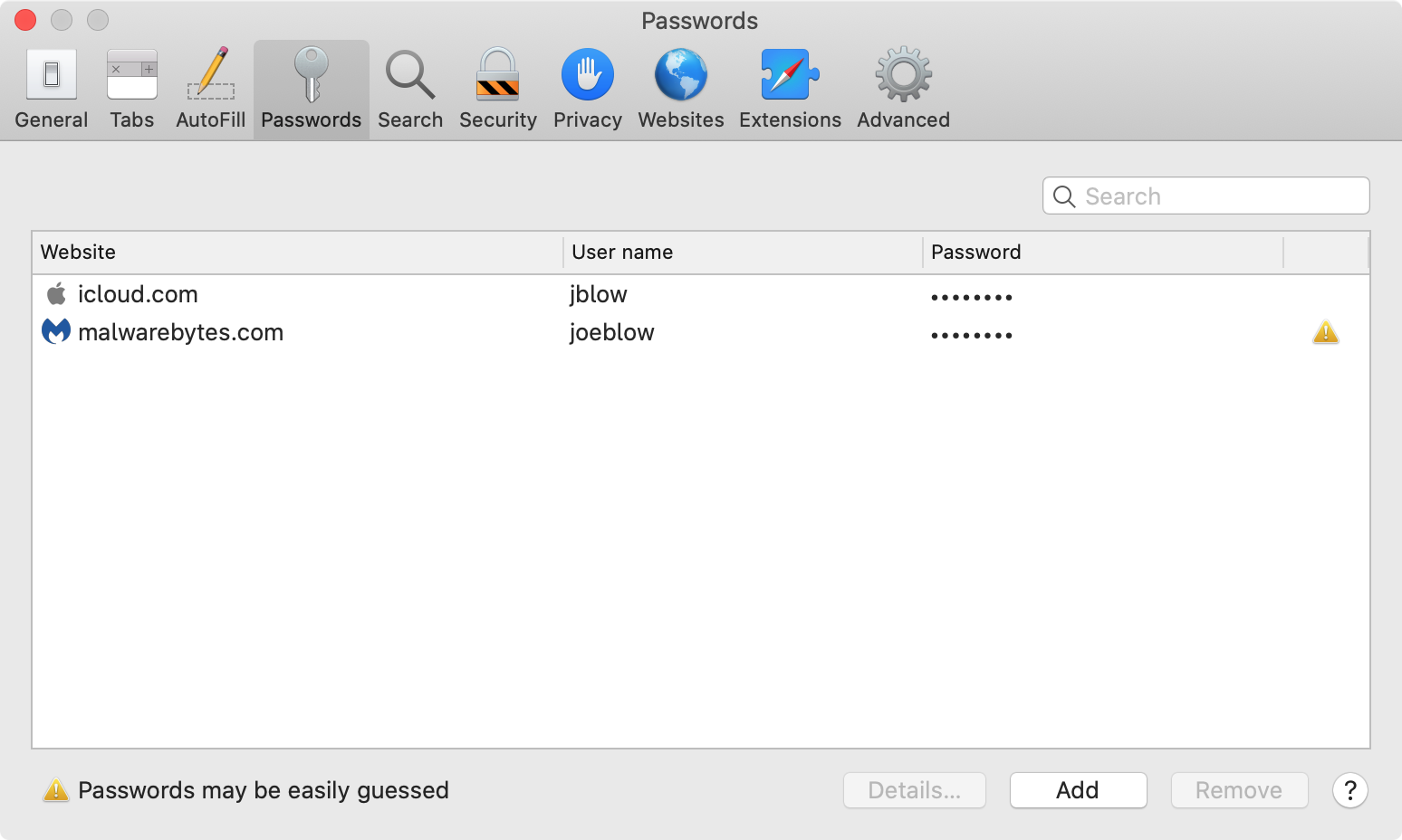

A password manager is a program designed to remember your passwords for you. Password managers can keep a list of not just your passwords, but also what site you’ve used them on, the username you use to log in to that site, any security questions you use on that site, etc.

A password manager can be as simple as a notebook you keep in a drawer in your desk. Of course, that’s also something that can be read by anyone with access to your office, and it’s not something you can easily carry around with you.

Password managers more typically come in the form of software, which can encrypt your passwords with a single master password, help you share them between devices, and much more.

You may have a password manager right at your fingertips already, as some web browsers have them built in. Examples include iCloud Keychain in Safari, Google Password Manager in Chrome, and the Firefox Password Manager.

If you use a more obscure browser, don’t want to use the built-in password manager, or just need something more powerful, you can consider something like 1Password or Lastpass.

Whatever fits your particular needs, use it. A password manager is the only way you can realistically have long, strong passwords that are different on every site. Your password manager’s “master” password becomes the only password you need to remember.

Creating a master password for your password manager follows the same, simple rules for your regular passwords—the longer the better. Since you’ll be typing this password in regularly, it could be easier to make a passphrase, which is a string of words that should have no direct meaning to you. Avoid birthdates and street addresses and lean into the chaos of your brain’s random word generator: something like “cantankerousbuffalopotteryhypothesis.”

Whoa, hold on a minute! Don’t walk away yet. Having good passwords and a way to store them is only a small part of the battle. After all, a good password is no good as soon as the site gets breached by a hacker and spills all its passwords. Believe it or not, there’s something else beyond the password.

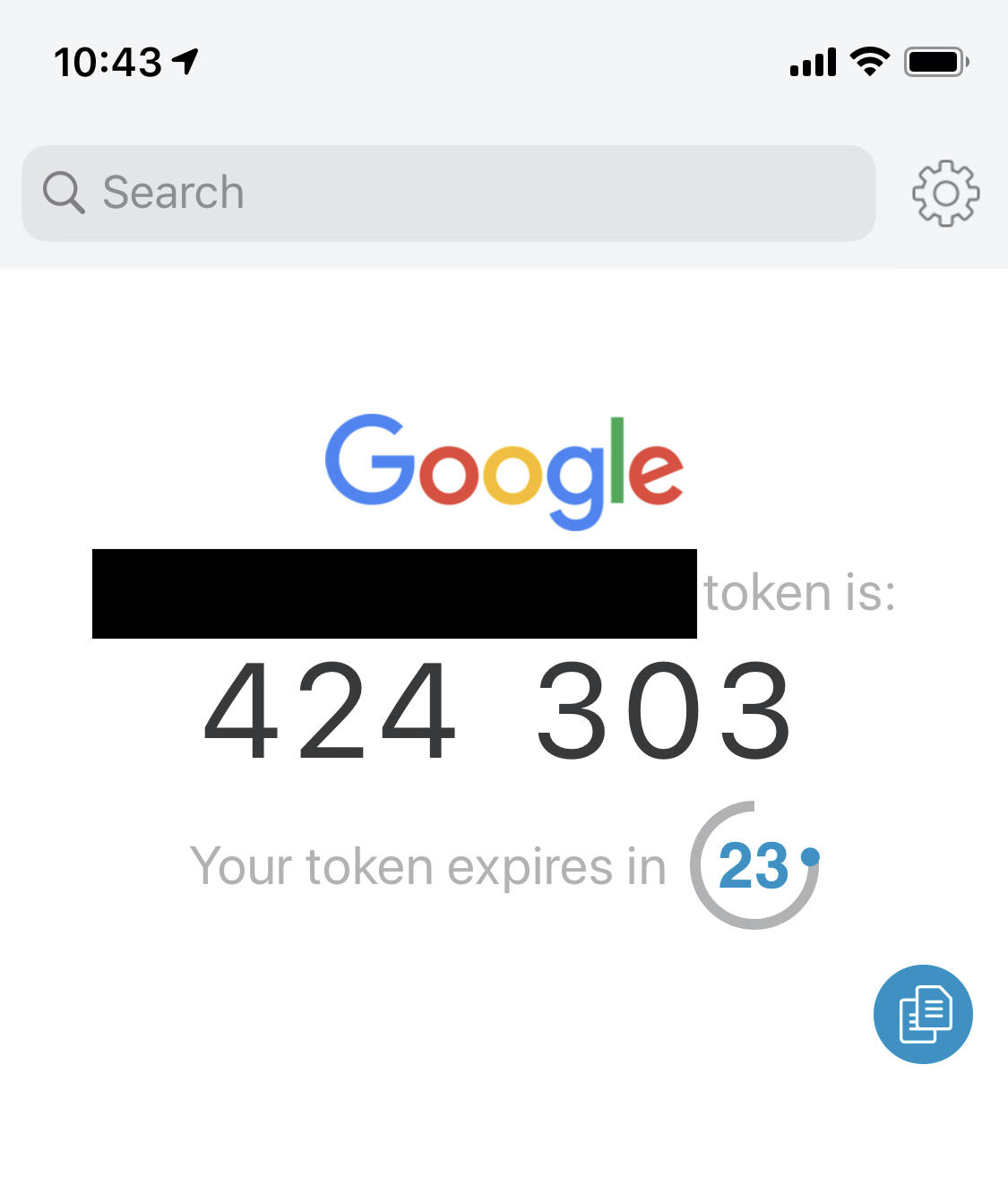

Step 3: Use two-factor authorization

Two-factor authorization (abbreviated 2FA) is some kind of secondary piece of information, in addition to a password, that can be required for you to log into a website. These typically are some kind of code—most commonly four or six digits—that you must enter during the login process.

The most common way to receive these codes is via text message on your phone. However, they can also be codes that change every 30 seconds, which are generated by a variety of different apps, such as Authy, Google Authenticator, or some more full-featured password managers. These are more secure than texted codes, but also less commonly supported, and codes sent to your phone via text message are better than nothing.

Whatever type your accounts support, use it. It can take some time to set this up these days, when people often have a LOT of accounts, so just take it a few at a time until you’re done.

For help figuring out what kinds of 2FA a site supports see the Two Factor Auth site. You can search this site for the site you’re interested in, and it will tell you what types of 2FA it supports (SMS and Software Token being the two types described above), and link you to that site’s documentation for how to set up 2FA.

For more information about 2FA, see Duo Security’s Two-Factor Authentication: The Basics.

Step 3a: What if there’s no 2FA?

Some sites don’t support 2FA, instead only supporting something like security questions… you know, “What’s the name of your first pet,” or “What street did you live on growing up,” and any number of other similar questions. Here’s the problem with these questions: they’re easy to guess, and the information may be public knowledge.

So, here’s what you do if security questions are all you have to secure a site: lie! Never, ever use true answers to security questions. Instead, make something up. For example, maybe say your first car was a “Millennium Falcon.” Or maybe you drove an “avocado toast.” Even better, say you drove a “dknO6RF%an!Fdke8.”

By now, I’m sure you’re not asking how you’re supposed to remember these ridiculous answers, because you know what the answer will be already: use your password manager. Most password managers support arbitrary notes, so add both the questions and the nonsensical answers to a note for that login in your password manager.

Wrapping up

If you skipped to the end without reading the details (we hope you did not), here’s the tl;dr: these messages are fake, there is no malware involved, and the only thing to be concerned about is the fact that one of your passwords is floating around in cyberspace.

Once you have followed all the instructions above to secure your online accounts, you’ll have nothing left to do, other than mark the message as junk and delete it (if you haven’t already).

Keep in mind that no antivirus software can prevent you from seeing these types of extortion messages. Email systems or clients that do junk mail (spam) filtering can help to catch some of these, but they cannot be relied on to catch all of them. These scammers are sneaky, and are good at evading junk mail filtering.

The fact that you keep receiving these extortion messages does not represent a security issue, and you do not need to be afraid of these thugs. They are only a threat to your wallet, and only if you fall for their tricks and send them money. Otherwise, they cannot do you any harm… so long as you’ve secured your accounts so they can’t use your leaked password against you.