In macOS Mojave, Apple introduced the concept of notarization, a process that developers can go through to ensure that their software is malware-free (and must go through for their software to run on macOS Catalina). This is meant to be another layer in Apple’s protection against malware. Unfortunately, it’s starting to look like notarization may be less security and more security theater.

What is notarization?

Notarization goes hand-in-hand with another security feature: code signing. So let’s talk about that first.

Code signing is a cryptographic process that enables a developer to provide authentication to their software. It both verifies who created the software and verifies the integrity of the software. By code signing an app, developers can (to some degree) prevent it from being modified maliciously—or at the very least, make such modifications easily detectable.

The code signing process has been integral to Mac software development for years. The user has to jump through hoops to run unsigned software, so little mainstream Mac software today comes unsigned.

However, Mac software that is distributed outside the App Store never had to go through any kind of checks. This meant that malware authors would obtain a code signing certificate from Apple (for a mere $99) and use that to sign their malware, enabling it to run without trouble. Of course, when discovered, Apple can revoke the code signing certificate, thus neutralizing the malware. However, malware can often go undiscovered for years, as illustrated best by the FruitFly malware, which went undetected for at least 10 years.

In light of this problem, Apple created a process they call “notarization.” This process involves developers submitting their software to Apple. That software goes through some kind of automated scan to ensure it doesn’t contain malware, and then is either rejected or notarized (i.e., certified as malware-free by Apple—in theory).

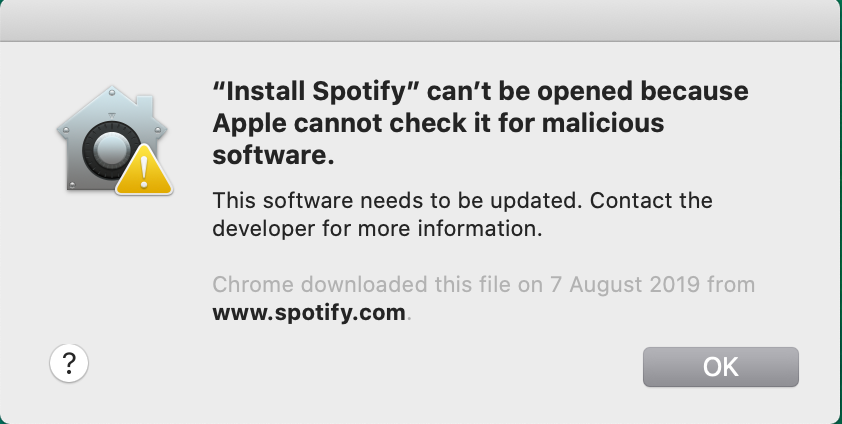

In macOS Catalina, software that is not notarized is prevented from running at all. If you try, you will simply be told “do not pass Go, do not collect $200.” (Or in Apple’s words, it can’t be opened because “Apple cannot check it for malicious software.”)

There are, of course, ways to run software that is not signed or not notarized, but there’s no indication as to how this is done from the error message, so as far as legitimate developers are concerned, it’s not an option.

So how’s that working out so far?

The big question on everyone’s minds when notarization was announced at Apple’s WWDC conference in 2019, was, “How effective is this going to be?” Many were quite optimistic that this would spell the end of Mac malware once and for all. However, those of us in the security industry did not drink the Kool-Aid. Turns out, our skepticism was warranted.

There are a couple tricks that the bad guys are using, in light of the new requirements. One is simple: Don’t sign or notarize the apps at all.

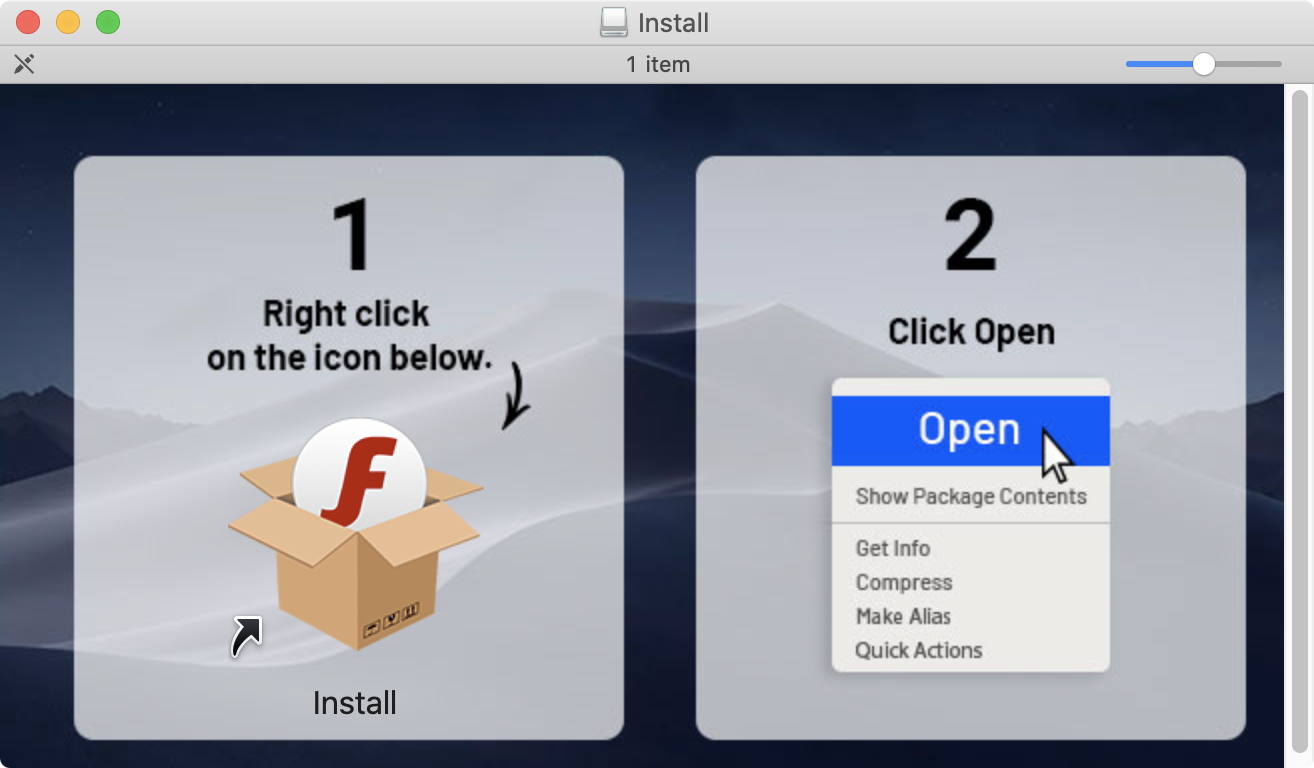

We’re seeing quite a few cases where malware authors have stopped signing their software, and have instead been shipping it with instructions to the user on how to run it.

As can be seen from the above screenshot, the malware comes on a disk image (.dmg) file with a custom background. That background image shows instructions for opening the software, which is neither signed nor notarized.

The irony here is that we see lots of people getting infected with this malware—a variant of the Shlayer or Bundlore adware, depending on who you ask—despite the minor difficulty of opening it. Meanwhile, the installation of security software on macOS has gotten to be so difficult that we get a fair number of support cases about it.

The other option, of course, is for threat actors to get their malware notarized.

Notarize malware?! Say it ain’t so!

In theory, the notarization process is supposed to weed out anything malicious. In practice, nobody really understands exactly how notarization works, and Apple is not inclined to share details. (For good reason—if they told the bad guys how they were checking for malware, the bad guys would know how to avoid getting caught by those checks.)

All developers and security researchers know is that notarization is fast. I’ve personally notarized software quite a few times at this point, and it usually takes less than a couple minutes between submission and receipt of the e-mail confirming success of notarization. That means there’s definitely no human intervention involved in the process, as there is with App Store reviews. Whatever it is, it’s solely automated.

I’ve assumed since notarization was first introduced that it would turn out to be fallible. I’ve even toyed with the idea of testing this process, though the risk of getting my developer account “Charlie Millered” has prevented me from doing so. (Charlie Miller is a well-known security researcher who created a proof-of-concept malware app and got it into the iOS App Store in 2011. Even though he notified Apple after getting the app approved, Apple still revoked his developer account and he has been banned from further Apple development activity ever since.)

It turns out, though, that all I had to do was wait for the bad guys to run the test for me. According to new findings, Mac security researcher Patrick Wardle has discovered samples of the Shlayer adware that are notarized. Yes, that’s correct. Apple’s notarization process has allowed known malware to pass through undetected, and to be implicitly vouched for by Apple.

How did they do that?

We’re still not exactly sure what the Shlayer folks did to get their malware notarized, but increasingly, it’s looking like they did nothing at all. On the surface, little has changed.

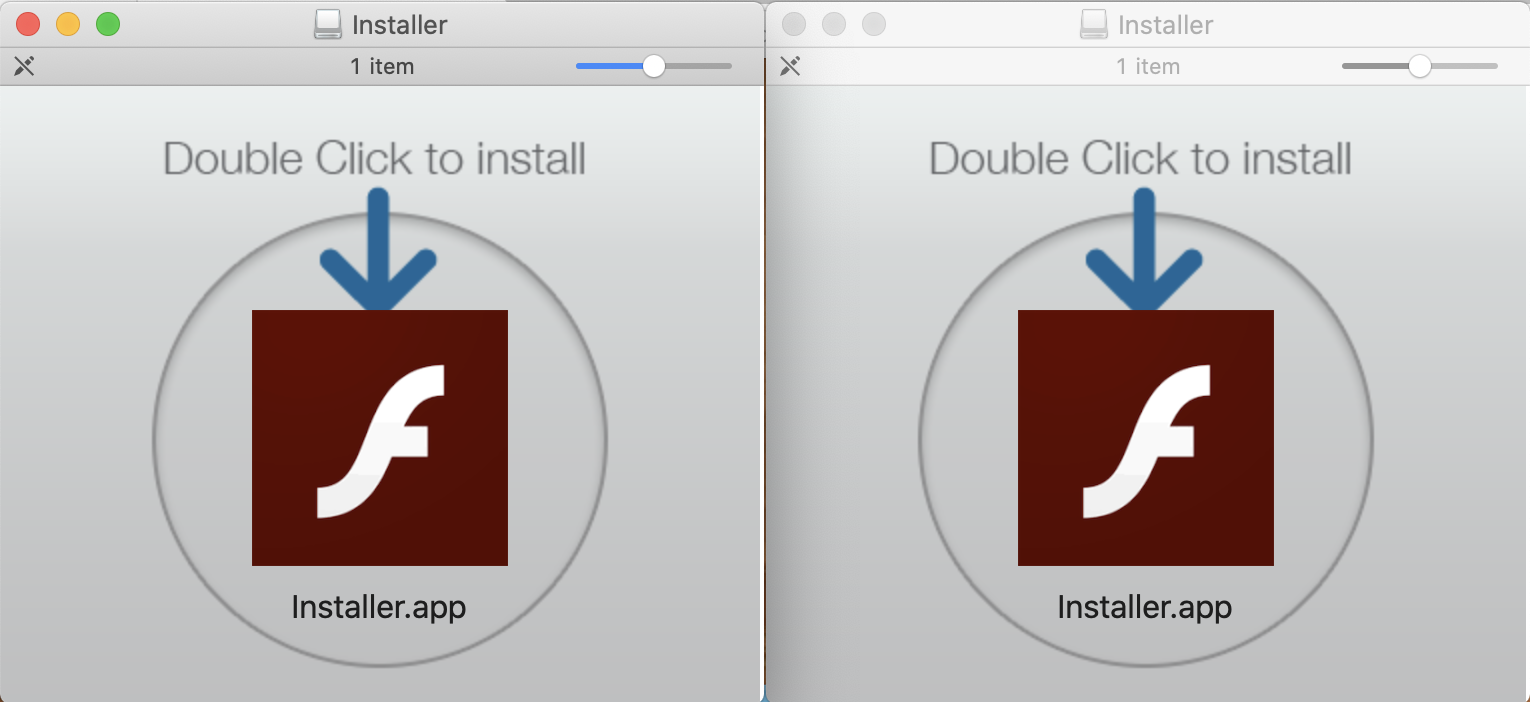

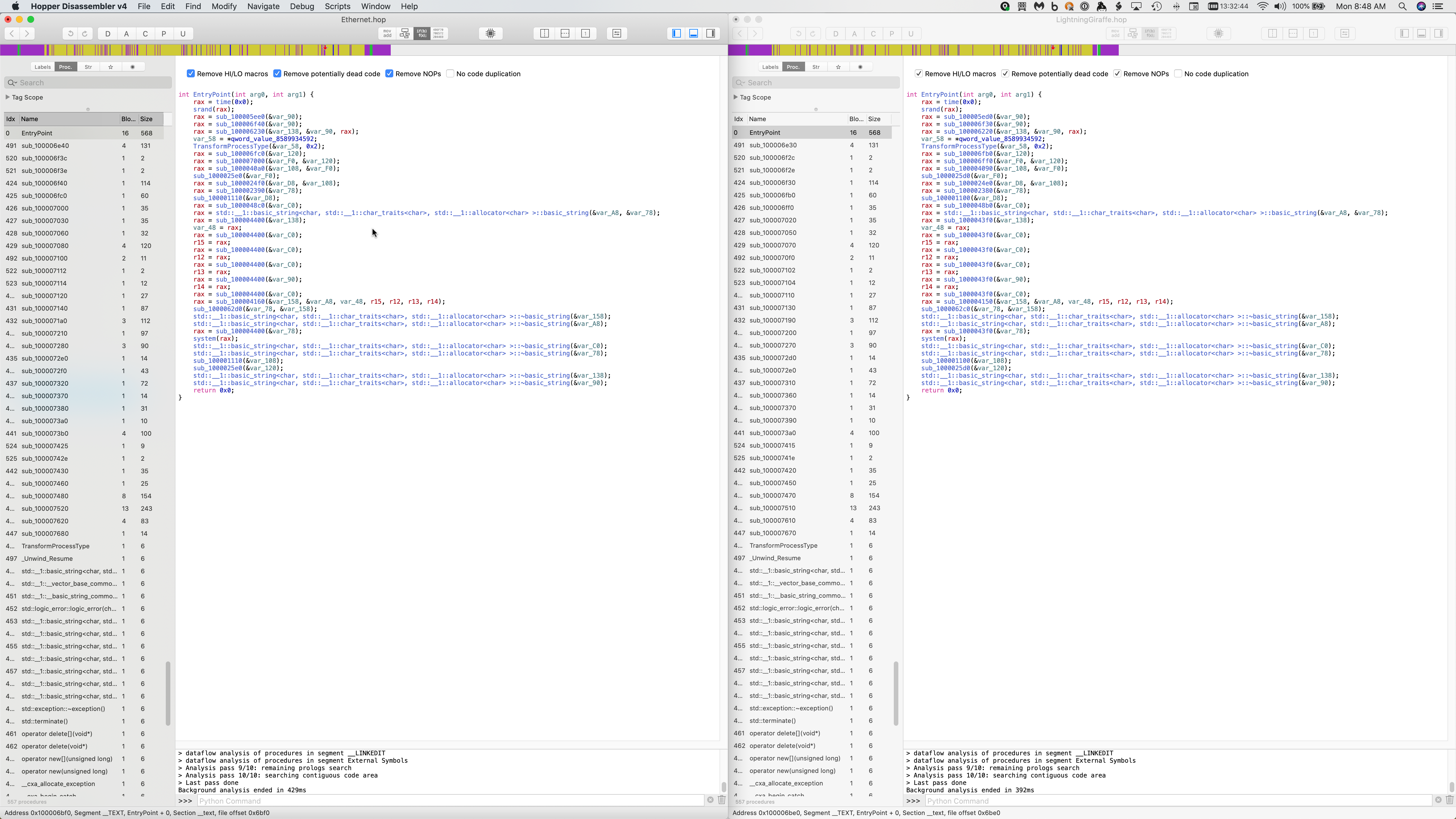

The above screenshot shows a notarized Shlayer sample on the left, and an older one on the right. There’s no difference at all in the appearance. But what about when you dive into the code?

This screenshot is hardly a comprehensive look into the code. It simply shows the entry point, and the names of a number of the functions found in the code. Still, at this level, any differences in the code are minor.

It’s entirely possible that something in this code, somewhere, was modified to break any detection that Apple might have had for this adware. Without knowing how (if?) Apple was detecting the older sample (shown on the right), it would be quite difficult to identify whether any changes were made to the notarized sample (on the left) that would break that detection.

This leaves us facing two distinct possibilities, neither of which is particularly appealing. Either Apple was able to detect Shlayer as part of the notarization process, but breaking that detection was trivial, or Apple had nothing in the notarization process to detect Shlayer, which has been around for a couple years at this point.

What does this mean?

This discovery doesn’t change anything from my perspective, as a skeptical and somewhat paranoid security researcher. However, it should help “normal” Mac users open their eyes and recognize that the Apple stamp does not automatically mean “safe.”

Apple wants you to believe that their systems are safe from malware. Although they no longer run the infamous “Macs don’t get viruses” ads, Apple never talks about malware publicly, and loves to give the impression that its systems are secure. Unfortunately, the opposite has been proven to be the case with great regularity. Macs—and iOS devices like iPhones and iPads, for that matter—are not invulnerable, and their built-in security mechanisms cannot protect users completely from infection.

Don’t get me wrong, I still use and love Mac and iOS devices. I don’t want to give the impression that they shouldn’t be used at all. It’s important to understand, though, that you must be just as careful with what you do with your Apple devices as you would be with your Windows or Android devices. And when in doubt, an extra layer of anti-malware protection goes a long way in providing peace of mind.