This year is finally coming to an end, and it only took us about eight consecutive months of March to get here. There is a ton to talk about, and that’s without even discussing the literal global pandemic.

You see, 2020’s news stories were the pressure-cooker product of mania, chaos, and the downright absurd. “Murder hornets” made the journey to the US. Mystery seeds from China arrived in US mailboxes. The Pentagon officially released three videos of “unidentified aerial phenomena”—which many interpreted as three videos of alien spacecraft.

Also, a star vanished. Yes. Brighter than our sun, nestled into the same distant galaxy that cradles the constellation of Aquarius, and glinting a pale, cornflower blue onto its neighbors, the massive star simply disappeared one day. No supernova. No stellar collapse. No black hole.

Honestly? Bravo, star.

So, in a year unbridled in strangeness, it only fits that the cybersecurity events we witnessed produced equally head-scratching responses. The following cybersecurity events of 2020 that we’ve collected for you are not the most destructive or the most shocking, or the most enticing, like we covered earlier this week. They are, instead, the mysteries, the embarrassments, and the face-palms.

They are the events that that made us collectively say: “Wait… seriously?”

A digital vaccine for a physical illness

We hate to start our jovial list with coronavirus news, but this was too incredulous to pass up.

In late March, we found threat actors trying to convince unsuspecting victims to install an alleged digital antivirus tool to protect themselves from the physical coronavirus. In the scheme, scam artists built a malicious website that advertised “Corona Antivirus -World’s best protection.”

The website also claimed:

“Our scientists from Harvard University have been working on a special AI development to combat the virus using a windows app. Your PC actively protects you against the Coronaviruses (Cov) while the app is running.”

Ugh.

What threat actors were hiding behind the website was an attempt to install the BlackNET Remote Access Trojan, which can deploy DDoS attacks, take screenshots, execute scripts, implement a keylogger, and steal Firefox cookies, passwords, and Bitcoin wallets.

TikTok: an on-again, off-again relationship

Back in December of 2019, the US Army banned its members from downloading the massively popular video sharing app TikTok on government-issued devices. At the time, Army spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Robin Ochoa described the app to the outlet Military.com as “a cyberthreat.”

Fast forward several months to the start of summer, when TikTok then received the worst kind of attention that any up-and-coming app can receive: that from a devoted Reddit user. The Reddit user claimed to have “reverse-engineered the app,” and said that TikTok was nothing more than “a data collection service that is thinly-veiled as a social network.” The app allegedly collected tons of data about users’ phones, the other apps they’ve installed, their network, and some GPS info.

The negative attention piled onto TikTok until, in August, President Donald Trump said he would ban the app from the US market.

With deadlines pressing, TikTok entered a flurry of sales talks, meeting with Microsoft, Oracle, and even Wal-Mart. A deal was initially struck with Oracle and Wal-Mart, with sign-off from the President granted partly in September. But the deal at the time still needed approval from a committee here in the US called the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS.

The way TikTok tells the story, that committee ghosted the company for months. As the company told the outlet The Verge:

“In the nearly two months since the President gave his preliminary approval to our proposal to satisfy those concerns, we have offered detailed solutions to finalize that agreement – but have received no substantive feedback on our extensive data privacy and security framework.”

So, did the administration claim a national security threat and then just… forget about it?

Data leakers suffer leaked data

In January, the FBI seized the domain of the website WeLeakData.com, which claimed to have more than 12 billion records that contained personal information that was pilfered from more than 10,000 data breaches. The website offered a “subscription” service, letting users buy access to the database for months at a time.

It was a pretty nefarious service and after the FBI seized the domain, the saga actually continued in May.

You see, an older database of WeLeakData.com itself actually leaked online, including information belonging to countless users who bought WeLeakData’s subscription services. Now, the tables had turned—login names, email addresses, hashed passwords, IP addresses, and even private messages between users were being sold and purchased online.

Shade ransomware operators turn to the light

In April, a group that claimed to have developed the Troldesh ransomware—also known as the Shade ransomware—publicly published all of its remaining decryption keys for anyone still suffering from an earlier attack.

Posting on GitHub, the group said:

“We are the team which created a trojan-encryptor mostly known as Shade, Troldesh or Encoder.858. In fact, we stopped its distribution in the end of 2019. Now we made a decision to put the last point in this story and to publish all the decryption keys we have (over 750 thousands at all). We are also publishing our decryption soft; we also hope that, having the keys, antivirus companies will issue their own more user-friendly decryption tools. All other data related to our activity (including the source codes of the trojan) was irrevocably destroyed. We apologize to all the victims of the trojan and hope that the keys we published will help them to recover their data.”

The decryption keys were real, and were even used by Kaspersky to help develop a decryption tool, which, in time, would be used by the No More Ransom initiative which helps victims of ransomware retrieve encrypted data without having to pay a ransom.

So, what changed these threat actors into threat solvers? A sudden clarity of the conscience? Or was it that Troldesh wasn’t really paying out anymore, so it wasn’t worth the trouble of keeping it running?

We don’t know, but we’re happy either way.

One password to ruin them all

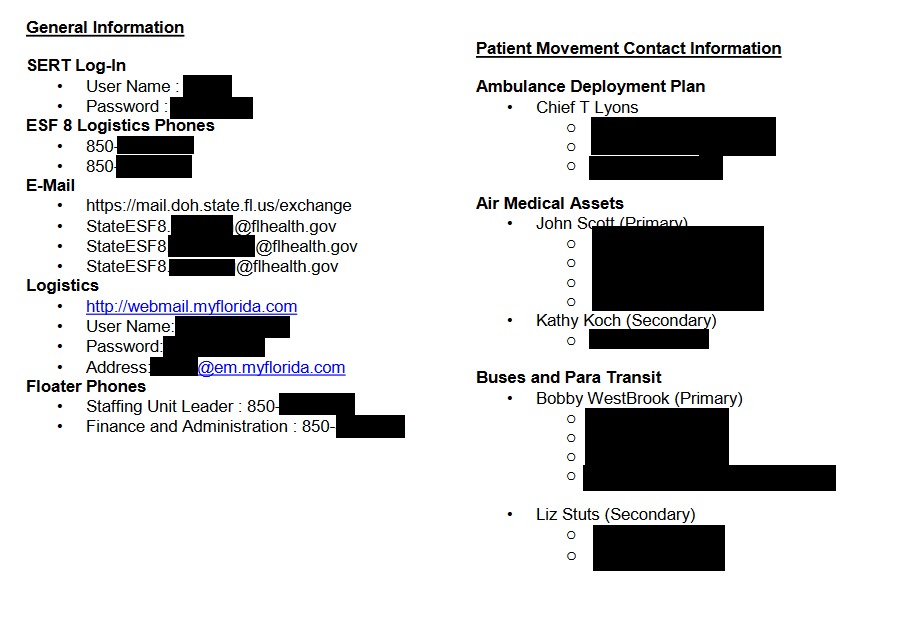

Earlier this month, Florida police raided the home of former government data scientist Rebekah Jones who, after being fired in May, had continued to post statistics about the state’s COVID-19 cases and deaths. The police said they investigated Jones because she had allegedly gained unauthorized access into the state’s emergency-responder system to send a wide alert to government employees.

But, according to Jones, that’s not true. Jones told CNN that she did not access the state’s emergency-responder system, and that she did not author the widely sent message.

When The Tampa Bay Times followed up with the Florida police to ask what measures they had implemented to safeguard the system, the police were tight-lipped.

According to Ars Technica, that stonewalling might be because the actual truth was far too embarrassing: Every single employee who logs into the system uses the same username and password, both of which are available to the public online.

Where’s the face-palm emoji?

Of printers and problems

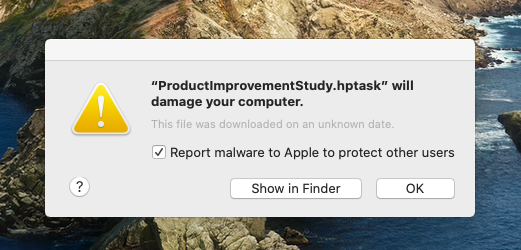

This Fall, we started getting reports about a new type of malware that we were allegedly not detecting, which was instead being reported by the built-in anti-malware features on macOS.

When we investigated further, though, we found that most of these “malware” reports were related to Hewlett-Packard (HP) printing drivers, and that many of the messages that users received generally popped up whenever those users had tried to print something on their HP printers. Curious, no?

The problem, we found, lied within certificates. What’s that? Allow us to explain.

Certificates help keep the Internet running. They are a way to verify that the server you connect to is really owned and operated by the business you’re trying to communicate with, like, say, your online bank. But for years now, Apple has increasingly pushed software developers into using certificates to cryptographically sign and verify their own software. Without developer signoff, software users will have a ton of trouble using that software on Apple devices.

Back to the HP printer problem. It turns out that an HP certificate that was used to sign HP drivers had been revoked. By who, you ask?

By HP! Seriously. As the company told The Register:

“We unintentionally revoked credentials on some older versions of Mac drivers. This caused a temporary disruption for those customers and we are working with Apple to restore the drivers.”

Unfortunately, we’re still getting reports of these problems today, and threat actors are jumping on the opportunities, setting up malicious websites that promise to fix the problem.

Dead eye

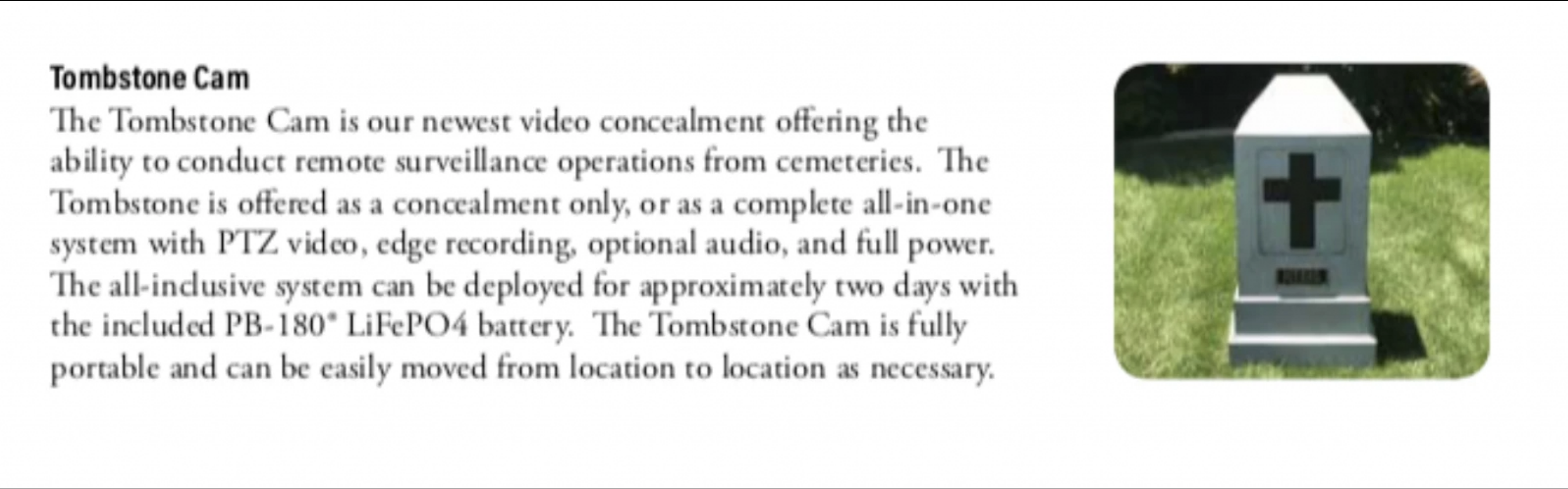

This is more of a digital surveillance story than a straight cybersecurity tale, but it deserved a place on our list as an honorable mention. This year, Motherboard revealed that a secretive company had been selling stealthy surveillance products to cops.

The products? Cameras hidden within vacuum cleaners, baby car seats, and gravestones.

Spooky!

To a new year

We’re almost in 2021, but a new day doesn’t magically bring new, improved cybersecurity across the globe. Instead, read the news, install antivirus, and protect yourself online. It’s the most clear-headed advice out there.