Schools in the US have been using surveillance software to keep an eye on their students, and such software has grown significantly in popularity since the COVD-19 pandemic closed campuses nationwide. And this is fine—at least according to new research released by the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) as a majority of parents (62 percent) and teachers (66 percent) believe that the benefits of digital surveillance outweighs the risks.

Monitoring software in schools have a range of capabilities that allow school administrators and districts to remotely:

- Block obscene material

- Track student logins to applications, including school and non-school related apps

- View the student’s screen in real-time

- Block non-educational material (e.g. YouTube)

- Close browser tabs

- Take control of student input capability

- Look at student browsing history

- Open and close applications

- Scan student conversations

Half of students surveyed also reveal that are “very or somewhat comfortable with the use of monitoring software”.

This, however, doesn’t mean that parents, teachers, and even students aren’t worried at all. In fact, they worry that such surveillance could backfire.

Both groups report they are aware of the privacy implications of using surveillance tech and how it would affect their behavior. Six in ten agreed to the statement: “I do not share my true thoughts or ideas because I know what I do online is being monitored”. The CDT also noted that 80 percent of these students are “more careful about what I search online when I know what I do online is being monitored.”

The 7-page report further states: “While a potential goal of student activity monitoring software is to prohibit access to obscene materials, these findings raise questions about whether tracking students may cause them to hesitate before accessing important resources (related to mental health, for instance).”

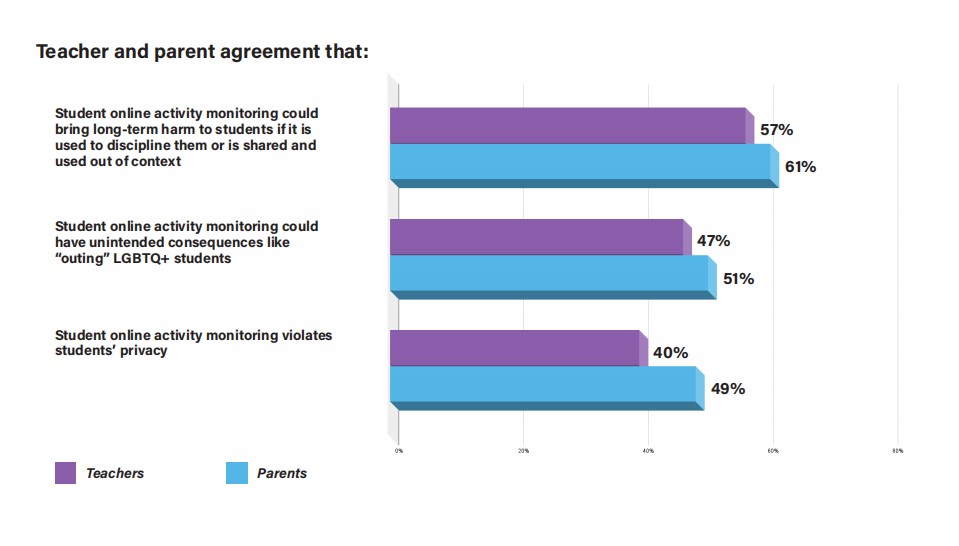

“Additionally, parents and teachers also express privacy concerns around the use of these tools, which include concerns about disciplinary applications as well as potential impacts on LGBTQ+ students and other unintended consequences.”

Data from the survey suggests that student monitoring software is largely used in K-12 schools. Such software is used more on school-issued devices than on personal devices. There are cases wherein schools don’t reveal that they use such software, and for those who are transparent in this regard, it’s not made clear how the software is being used or how long the software is active.

In some cases, security flaws in these monitoring software have allowed schools and districts to access students’ cameras and microphones without their knowledge or consent.

Companies that sell surveillance software and services often claim that their software protects student safety and supports academic achievement. School administrators go to them because they believe that such companies could help them comply with Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) standards. CIPA requires that schools have an Internet safety polity that “…includes technology protection measures. The protection measures must block or filter Internet access to pictures that are: (a) obscene; (b) child pornography; or (c) harmful to minors…”.

The CDT believes, however, that school administrators’ belief are misplaced.

Elizabeth Laird, who co-authored the CDT report, has expressed concern that such surveillance in schools could particularly impact youth of color and those in low-income households whose only way of getting and staying connected to the internet is by using school-issued devices. The more they are online using such devices outside of school, the more likely their activities are being monitored. The security and privacy that come with owning a personal device are things of luxury to them.

In a February 2020 article, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s (EFF) Mona Wang and Gennie Gebhart wrote that “schools are experimenting with the very same surveillance technologies that totalitarian governments use to surveil and abuse the rights of their citizens everywhere: online, offline, and on their phones. What does that mean? We are surveilling our students as if they were dissidents under an authoritarian regime.”

“Schools refer to these technologies as ‘student safety’ measures, but this label doesn’t change the fact that these are surveillance technologies. Surveillance is surveillance is surveillance.”

To help bring the growing problem of school surveillance to light, the CDT—along with other organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Center for Learner Equity (to name a few)—submitted a letter urging federal lawmakers to protect students’ rights to privacy, expression, and safety by amending CIPA to include a clarification clause that it does not require schools or districts to constantly, broadly, and invasively monitor students lives online.

“Systemic monitoring of online activity can reveal sensitive information about students’ personal lives, such as their sexual orientation, or cause a chilling effect on their free expression, political organizing, or discussion of sensitive issues such as mental health,” the letter states. “These harms likely fall disproportionately on already vulnerable, over-policed, and over-disciplined communities and may be exacerbated when monitoring occurs on devices and services used off-campus, including in students’ homes.”